Absurdism

In philosophy, "the Absurd" refers to the conflict between the human tendency to seek inherent value and meaning in life, and the human inability to find any in a purposeless, meaningless or chaotic and irrational universe.[1] The universe and the human mind do not each separately cause the Absurd, but rather, the Absurd arises by the contradictory nature of the two existing simultaneously.

As a philosophy, absurdism furthermore explores the fundamental nature of the Absurd and how individuals, once becoming conscious of the Absurd, should respond to it. The absurdist philosopher Albert Camus stated that individuals should embrace the absurd condition of human existence. He then promotes life rich in willful experience.[2]

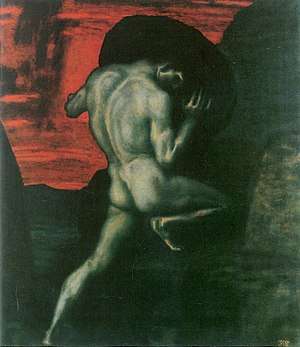

Absurdism shares some concepts, and a common theoretical template, with existentialism and nihilism. It has its origins in the work of the 19th-century Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard, who chose to confront the crisis that humans face with the Absurd by developing his own existentialist philosophy.[3] Absurdism as a belief system was born of the European existentialist movement that ensued, specifically when Camus rejected certain aspects of that philosophical line of thought[4] and published his essay The Myth of Sisyphus. The aftermath of World War II provided the social environment that stimulated absurdist views and allowed for their popular development, especially in the devastated country of France.

Overview

– Søren Kierkegaard, The Sickness Unto Death[5]

In absurdist philosophy, the Absurd arises out of the fundamental disharmony between the individual's search for meaning and the meaninglessness of the universe. As beings looking for meaning in a meaningless world, humans have three ways of resolving the dilemma. Kierkegaard and Camus describe the solutions in their works, The Sickness Unto Death (1849) and The Myth of Sisyphus (1942), respectively:

- Suicide (or, "escaping existence"): a solution in which a person ends one's own life. Both Kierkegaard and Camus dismiss the viability of this option. Camus states that it does not counter the Absurd. Rather, in the act of ending one's existence, one's existence only becomes more absurd.

- Religious, spiritual, or abstract belief in a transcendent realm, being, or idea: a solution in which one believes in the existence of a reality that is beyond the Absurd, and, as such, has meaning. Kierkegaard stated that a belief in anything beyond the Absurd requires an irrational but perhaps necessary religious "leap" into the intangible and empirically unprovable (now commonly referred to as a "leap of faith"). However, Camus regarded this solution, and others, as "philosophical suicide".

- Acceptance of the Absurd: a solution in which one accepts the Absurd and continues to live in spite of it. Camus endorsed this solution, believing that by accepting the Absurd, one can achieve the greatest extent of one's freedom. By recognizing no religious or other moral constraints, and by rebelling against the Absurd (through meaning-making) while simultaneously accepting it as unstoppable, one could find contentment through the transient personal meaning constructed in the process. Kierkegaard, on the other hand, regarded this solution as "demoniac madness": "He rages most of all at the thought that eternity might get it into its head to take his misery from him!"[6]

Relationship to existentialism and nihilism

Absurdism originated from (as well as alongside) the 20th-century strains of existentialism and nihilism; it shares some prominent starting points with both, though also entails conclusions that are uniquely distinct from these other schools of thought. All three arose from the human experience of anguish and confusion stemming from the Absurd: the apparent meaninglessness in a world in which humans, nevertheless, are compelled to find or create meaning.[7] The three schools of thought diverge from there. Existentialists have generally advocated the individual's construction of his or her own meaning in life as well as the free will of the individual. Nihilists, on the contrary, contend that "it is futile to seek or to affirm meaning where none can be found."[8] Absurdists, following Camus's formulation, hesitantly allow the possibility for some meaning or value in life, but are neither as certain as existentialists are about the value of one's own constructed meaning nor as nihilists are about the total inability to create meaning. Absurdists following Camus also devalue or outright reject free will, encouraging merely that the individual live defiantly and authentically in spite of the psychological tension of the Absurd.[9]

Camus himself passionately worked to counter nihilism, as he explained in his essay "The Rebel," while he also categorically rejected the label of "existentialist" in his essay "Enigma" and in the compilation The Lyrical and Critical Essays of Albert Camus, though he was, and still is, often broadly characterized by others as an existentialist.[10] Both existentialism and absurdism entail consideration of the practical applications of becoming conscious of the truth of existential nihilism: i.e., how a driven seeker of meaning should act when suddenly confronted with the seeming concealment, or downright absence, of meaning in the universe. Camus's own understanding of the world (e.g., "a benign indifference", in The Stranger), and every vision he had for its progress, however, sets him apart from the general existentialist trend.

|

Such a chart represents some of the overlap and tensions between existentialist and absurdist approaches to meaning. While absurdism can be seen as a kind of response to existentialism, it can be debated exactly how substantively the two positions differ from each other. The existentialist, after all, doesn't deny the reality of death. But the absurdist seems to reaffirm the way in which death ultimately nullifies our meaning-making activities, a conclusion the existentialists seem to resist through various notions of posterity or, in Sartre's case, participation in a grand humanist project.

Søren Kierkegaard

A century before Camus, the 19th century Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard wrote extensively about the absurdity of the world. In his journals, Kierkegaard writes about the absurd:

What is the Absurd? It is, as may quite easily be seen, that I, a rational being, must act in a case where my reason, my powers of reflection, tell me: you can just as well do the one thing as the other, that is to say where my reason and reflection say: you cannot act and yet here is where I have to act... The Absurd, or to act by virtue of the absurd, is to act upon faith ... I must act, but reflection has closed the road so I take one of the possibilities and say: This is what I do, I cannot do otherwise because I am brought to a standstill by my powers of reflection.[13]

— Kierkegaard, Søren, Journals, 1849

Here is another example of the Absurd from his writings:

What, then, is the absurd? The absurd is that the eternal truth has come into existence in time, that God has come into existence, has been born, has grown up. etc., has come into existence exactly as an individual human being, indistinguishable from any other human being, in as much as all immediate recognizability is pre-Socratic paganism and from the Jewish point of view is idolatry.

—Kierkegaard, Concluding Unscientific Postscript, 1846, Hong 1992, p. 210

How can this absurdity be held or believed? Kierkegaard says:

I gladly undertake, by way of brief repetition, to emphasize what other pseudonyms have emphasized. The absurd is not the absurd or absurdities without any distinction (wherefore Johannes de Silentio: "How many of our age understand what the absurd is?"). The absurd is a category, and the most developed thought is required to define the Christian absurd accurately and with conceptual correctness. The absurd is a category, the negative criterion, of the divine or of the relationship to the divine. When the believer has faith, the absurd is not the absurd — faith transforms it, but in every weak moment it is again more or less absurd to him. The passion of faith is the only thing which masters the absurd — if not, then faith is not faith in the strictest sense, but a kind of knowledge. The absurd terminates negatively before the sphere of faith, which is a sphere by itself. To a third person the believer relates himself by virtue of the absurd; so must a third person judge, for a third person does not have the passion of faith. Johannes de Silentio has never claimed to be a believer; just the opposite, he has explained that he is not a believer — in order to illuminate faith negatively.

—Journals of Søren Kierkegaard X6B 79[14]

Kierkegaard provides an example in Fear and Trembling (1843), which was published under the pseudonym Johannes de Silentio. In the story of Abraham in the Book of Genesis, Abraham is told by God to kill his son Isaac. Just as Abraham is about to kill Isaac, an angel stops Abraham from doing so. Kierkegaard believes that through virtue of the absurd, Abraham, defying all reason and ethical duties ("you cannot act"), got back his son and reaffirmed his faith ("where I have to act").[15]

Another instance of absurdist themes in Kierkegaard's work appears in The Sickness Unto Death, which Kierkegaard signed with pseudonym Anti-Climacus. Exploring the forms of despair, Kierkegaard examines the type of despair known as defiance.[16] In the opening quotation reproduced at the beginning of the article, Kierkegaard describes how such a man would endure such a defiance and identifies the three major traits of the Absurd Man, later discussed by Albert Camus: a rejection of escaping existence (suicide), a rejection of help from a higher power and acceptance of his absurd (and despairing) condition.

According to Kierkegaard in his autobiography The Point of View of My Work as an Author, most of his pseudonymous writings are not necessarily reflective of his own opinions. Nevertheless, his work anticipated many absurdist themes and provided its theoretical background.

Albert Camus

Though the notion of the 'absurd' pervades all Albert Camus's writing, The Myth of Sisyphus is his chief work on the subject. In it, Camus considers absurdity as a confrontation, an opposition, a conflict or a "divorce" between two ideals. Specifically, he defines the human condition as absurd, as the confrontation between man's desire for significance, meaning and clarity on the one hand – and the silent, cold universe on the other. He continues that there are specific human experiences evoking notions of absurdity. Such a realization or encounter with the absurd leaves the individual with a choice: suicide, a leap of faith, or recognition. He concludes that recognition is the only defensible option.[17]

For Camus, suicide is a "confession" that life is not worth living; it is a choice that implicitly declares that life is "too much." Suicide offers the most basic "way out" of absurdity: the immediate termination of the self and its place in the universe.

The absurd encounter can also arouse a "leap of faith," a term derived from one of Kierkegaard's early pseudonyms, Johannes de Silentio (although the term was not used by Kierkegaard himself),[18] where one believes that there is more than the rational life (aesthetic or ethical). To take a "leap of faith," one must act with the "virtue of the absurd" (as Johannes de Silentio put it), where a suspension of the ethical may need to exist. This faith has no expectations, but is a flexible power initiated by a recognition of the absurd. (Although at some point, one recognizes or encounters the existence of the Absurd and, in response, actively ignores it.) However, Camus states that because the leap of faith escapes rationality and defers to abstraction over personal experience, the leap of faith is not absurd. Camus considers the leap of faith as "philosophical suicide," rejecting both this and physical suicide.[18][19]

Lastly, a person can choose to embrace the absurd condition. According to Camus, one's freedom – and the opportunity to give life meaning – lies in the recognition of absurdity. If the absurd experience is truly the realization that the universe is fundamentally devoid of absolutes, then we as individuals are truly free. "To live without appeal,"[20] as he puts it, is a philosophical move to define absolutes and universals subjectively, rather than objectively. The freedom of humans is thus established in a human's natural ability and opportunity to create their own meaning and purpose; to decide (or think) for him- or herself. The individual becomes the most precious unit of existence, representing a set of unique ideals that can be characterized as an entire universe in its own right. In acknowledging the absurdity of seeking any inherent meaning, but continuing this search regardless, one can be happy, gradually developing meaning from the search alone.

Camus states in The Myth of Sisyphus: "Thus I draw from the absurd three consequences, which are my revolt, my freedom, and my passion. By the mere activity of consciousness I transform into a rule of life what was an invitation to death, and I refuse suicide."[21] "Revolt" here refers to the refusal of suicide and search for meaning despite the revelation of the Absurd; "Freedom" refers to the lack of imprisonment by religious devotion or others' moral codes; "Passion" refers to the most wholehearted experiencing of life, since hope has been rejected, and so he concludes that every moment must be lived fully.

See also

- Absurdist fiction

- Credo quia absurdum

- Discordianism

- Existential nihilism

- Existentialism

- Irrationality

- Is-ought problem

- Fact-value distinction

- Lottery of birth

- Meaning of life

- Nihilism

- Non sequitur (literary device)

- 'Pataphysics

- Peter Wessel Zapffe

- The Stranger (novel)

- Theatre of the Absurd

- Absurdistan

- Church of the SubGenius

- Terror management theory

- Use–mention distinction

References

- Dotterweich, John (March 11, 2019). "An Argument for the Absurd". Southern Cross University. Retrieved October 8, 2019.

- Aronson, Ronald (2011-10-27). "Albert Camus". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2019-12-8.

- Stewart, Jon (2011). Kierkegaard and Existentialism. Farnham, England: Ashgate. ISBN 978-1-4094-2641-7. pp. 76–78.

- Solomon, Robert C. (2001). From Rationalism to Existentialism: The Existentialists and Their Nineteenth Century Backgrounds. Rowman and Littlefield. p. 245. ISBN 0-7425-1241-X.

- Kierkegaard, Søren (1941). The Sickness Unto Death. Princeton University Press.

- Kierkegaard, Søren (1941). The Sickness Unto Death. Princeton University Press. Part I, Ch. 3.

- Alan Pratt (April 23, 2001). "Nihilism". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Embry-Riddle University. Retrieved February 4, 2012.

- Donald A. Crosby (July 1, 1988). The Specter of the Absurd: Sources and Criticisms of Modern Nihilism. State University of New York Press. Retrieved January 29, 2012.

- "Albert Camus". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

What is the Camusean alternative to suicide or hope? The answer is to live without escape and with integrity, in “revolt” and defiance, maintaining the tension intrinsic to human life

- Solomon, Robert C. (2001). From Rationalism to Existentialism: The Existentialists and Their Nineteenth Century Backgrounds. Rowman and Littlefield. p. 245. ISBN 0-7425-1241-X.

- "Albert Camus". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

What is the Camusean alternative to suicide or hope? The answer is to live without escape and with integrity, in “revolt” and defiance, maintaining the tension intrinsic to human life

- Kierkegaard, Søren. The Sickness Unto Death. Kierkegaard wrote about all four viewpoints in his works at one time or another, but the majority of his work leaned towards what would later become absurdist and theistic existentialist views.

- Dru, Alexander. The Journals of Søren Kierkegaard, Oxford University Press, 1938.

- "Søren Kierkegaard". Naturalthinker.com. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- Silentio, Johannes de. Fear and Trembling, Denmark, 1843

- Sickness Unto Death, Ch.3, part B, sec. 2

- Camus, Albert (1991). Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays. Vintage Books. ISBN 0-679-73373-6.

- "The Kierkegaardian Leap" in The Cambridge Companion to Kierkegaard.

- Camus, Myth of Sisyphus, p. 41

- Camus, Myth of Sisyphus, p. 55

- Camus, Myth of Sisyphus, p. 64

Further reading

- OBERIU, edited by Eugene Ostashevsky. Northwestern University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-8101-2293-6

- Thomas Nagel: Mortal Questions, 1991. ISBN 0-521-40676-5

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Absurdism |