Sutra

Sutra (Sanskrit: सूत्र, romanized: sūtra, lit. 'string, thread[1]') in Indian literary traditions refers to an aphorism or a collection of aphorisms in the form of a manual or, more broadly, a condensed manual or text. Sutras are a genre of ancient and medieval Indian texts found in Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism.[2][1]

In Hinduism, sutras are a distinct type of literary composition, a compilation of short aphoristic statements.[2][3] Each sutra is any short rule, like a theorem distilled into few words or syllables, around which teachings of ritual, philosophy, grammar, or any field of knowledge can be woven.[1][2] The oldest sutras of Hinduism are found in the Brahmana and Aranyaka layers of the Vedas.[4][5] Every school of Hindu philosophy, Vedic guides for rites of passage, various fields of arts, law, and social ethics developed respective sutras, which help teach and transmit ideas from one generation to the next.[3][6][7]

In Buddhism, sutras, also known as suttas, are canonical scriptures, many of which are regarded as records of the oral teachings of Gautama Buddha. They are not aphoristic, but are quite detailed, sometimes with repetition. This may reflect a philological root of sukta (well spoken), rather than sutra (thread).[8]

In Jainism, sutras also known as suyas are canonical sermons of Mahavira contained in the Jain Agamas as well as some later (post-canonical) normative texts.[9][10]

Etymology

The Sanskrit word Sūtra (Sanskrit: सूत्र, Pali: sūtta, Ardha Magadhi: sūya) means "string, thread".[1][2] The root of the word is siv, that which sews and holds things together.[1][12] The word is related to sūci (Sanskrit: सूचि) meaning "needle, list",[13] and sūnā (Sanskrit: सूना) meaning "woven".[1]

In the context of literature, sūtra means a distilled collection of syllables and words, any form or manual of "aphorism, rule, direction" hanging together like threads with which the teachings of ritual, philosophy, grammar, or any field of knowledge can be woven.[1][2]

A sūtra is any short rule, states Moriz Winternitz, in Indian literature; it is "a theorem condensed in few words".[2] A collection of sūtras becomes a text, and this is also called sūtra (often capitalized in Western literature).[1][2]

A sūtra is different from other components such as Shlokas, Anuvyakhayas and Vyakhyas found in ancient Indian literature.[14] A sūtra is a condensed rule which succinctly states the message,[15] while a Shloka is a verse that conveys the complete message and is structured to certain rules of musical meter,[16][17] a Anuvyakhaya is an explanation of the reviewed text, while a Vyakhya is a comment by the reviewer.[14][18]

History

| Veda | Sutras |

| Rigveda | Asvalayana Sutra (§), Sankhayana Sutra (§), Saunaka Sutra (¶) |

| Samaveda | Latyayana Sutra (§), Drahyayana Sutra (§), Nidana Sutra (§), Pushpa Sutra (§), Anustotra Sutra (§)[20] |

| Yajurveda | Manava Sutra (§), Bharadvaja Sutra (¶), Vadhuna Sutra (¶), Vaikhanasa Sutra (¶), Laugakshi Sutra (¶), Maitra Sutra (¶), Katha Sutra (¶), Varaha Sutra (¶) |

| Atharvaveda | Kusika Sutra (§) |

| ¶: only quotes survive; §: text survives | |

Sutras first appear in the Brahmana and Aranyaka layer of Vedic literature.[5] They grow in the Vedangas, such as the Shrauta Sutras and Kalpa Sutras.[1] These were designed so that they can be easily communicated from a teacher to student, memorized by the recipient for discussion or self-study or as reference.[2]

A sutra by itself is condensed shorthand, and the threads of syllable are difficult to decipher or understand, without associated scholarly Bhasya or deciphering commentary that fills in the "woof".[21][22]

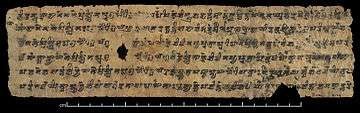

The oldest manuscripts that have survived into the modern era, that contain extensive sutras, are part of the Vedas dated to be from the late 2nd millennium BCE through mid 1st-millennium BCE.[23] The Aitareya Aranyaka for example, states Winternitz, is primarily a collection of sutras.[5] Their use and ancient roots are attested by sutras being mentioned in larger genre of ancient non-Vedic Hindu literature called Gatha, Narashansi, Itihasa, and Akhyana (songs, legends, epics, and stories).[24]

In the history of Indian literature, large compilations of sutras, in diverse fields of knowledge, have been traced to the period from 600 BCE to 200 BCE (mostly after Buddha and Mahavira), and this has been called the "sutras period".[24][25] This period followed the more ancient Chhandas period, Mantra period and Brahmana period.[26]

(The ancient) Indian pupil learnt these sutras of grammar, philosophy or theology by the same mechanical method which fixes in our (modern era) minds the alphabet and the multiplication table.

— Max Muller, History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature[6]

Hinduism

Some of the earliest surviving specimen of sutras of Hinduism are found in the Anupada Sutras and Nidana Sutras.[27] The former distills the epistemic debate whether Sruti or Smriti or neither must be considered the more reliable source of knowledge,[28] while the latter distills the rules of musical meters for Samaveda chants and songs.[29]

A larger collection of ancient sutra literature in Hinduism corresponds to the six Vedangas, or six limbs of the Vedas.[4] These are six subjects that were called in the Vedas as necessary for complete mastery of the Vedas. The six subjects with their own sutras were "pronunciation (Shiksha), meter (Chandas), grammar (Vyakarana), explanation of words (Nirukta), time keeping through astronomy (Jyotisha), and ceremonial rituals (Kalpa).[4] The first two, states Max Muller, were considered in the Vedic era to be necessary for reading the Veda, the second two for understanding it, and the last two for deploying the Vedic knowledge at yajnas (fire rituals).[4] The sutras corresponding to these are embedded inside the Brahmana and Aranyaka layers of the Vedas. Taittiriya Aranyaka, for example in Book 7, embeds sutras for accurate pronunciation after the terse phrases "On Letters", "On Accents", "On Quantity", "On Delivery", and "On Euphonic Laws".[30]

The fourth and often the last layer of philosophical, speculative text in the Vedas, the Upanishads, too have embedded sutras such as those found in the Taittiriya Upanishad.[30]

The compendium of ancient Vedic sutra literature that has survived, in full or fragments, includes the Kalpa Sutras, Smarta Sutras, Srauta Sutras, Dharma Sutras, Grhya Sutras, and Sulba Sutras.[31] Other fields for which ancient sutras are known include etymology, phonetics, and grammar.

Post-vedic sutras

अथातो ब्रह्मजिज्ञासा ॥१.१.१॥

जन्माद्यस्य यतः ॥ १.१.२॥

शास्त्रयोनित्वात् ॥ १.१.३॥

तत्तुसमन्वयात् ॥ १.१.४॥

ईक्षतेर्नाशब्दम् ॥ १.१.५॥

Some examples of sutra texts in various schools of Hindu philosophy include:

- Brahma Sutras (or Vedanta Sutra) – a Sanskrit text, composed by Badarayana, likely sometime between 200 BCE to 200 CE.[34] The text contains 555 sutras in four chapters that summarize the philosophical and spiritual ideas in the Upanishads.[35] It is one of the foundational texts of the Vedānta school of Hindu philosophy.[35]

- Yoga Sutras – contains 196 sutras on Yoga including the eight limbs and meditation. The Yoga Sutras were compiled around 400 CE by Patanjali, taking materials about yoga from older traditions.[36] The text has been highly influential on Indian culture and spiritual traditions, and it is among the most translated ancient Indian text in the medieval era, having been translated into about forty Indian languages.[37]

- Samkhya Sutra – is a collection of major Sanskrit texts of the Samkhya school of Hindu philosophy, including the sutras on dualism of Kapila.[38] It consists of six books with 526 sutras.

Sutra, without commentary:

Soul is, for there is no proof that it is not. (Sutra 1, Book 6) This different from body, because heterogeneous. (Sutra 2, Book 6) Also because it is expressed by means of the sixth. (Sutra 3, Book 6)

With Vijnanabhiksu's commentary bhasya filled in:

Soul is, for there is no proof that it is not, since we are aware of "I think", because there is no evidence to defeat this. Therefore all that is to be done is to discriminate it from things in general. (Sutra 1, Book 6) This soul is different from the body because of heterogeneous or complete difference between the two. (Sutra 2, Book 6) Also because it, the Soul, is expressed by means of the sixth case, for the learned express it by the possessive case in such examples as 'this is my body', 'this my understanding'; for the possessive case would be unaccountable if there were absolute non-difference, between the body or the like, and the Soul to which it is thus attributed as a possession. (Sutra 3, Book 6)

– Kapila in Samkhya Sutra, Translated by James Robert Ballantyne[39][40]

- Vaisheshika Sutra – the foundational text of the Vaisheshika school of Hinduism, dated to between 4th-century BCE to 1st-century BCE, authored by Kanada.[41] With 370 sutras, it aphoristically teaches non-theistic naturalism, epistemology, and its metaphysics. The first two sutras of the text expand as, "Now an explanation of Dharma; The means to prosperity and salvation is Dharma."[41][42]

- Nyaya Sutras – an ancient text of Nyaya school of Hindu philosophy composed by Akṣapada Gautama, sometime between 6th-century BCE to 2nd-century CE.[43][44] It is notable for focusing on knowledge and logic, and making no mention of Vedic rituals.[43] The text includes 528 aphoristic sutras, about rules of reason, logic, epistemology, and metaphysics.[45][46] These sutras are divided into five books, with two chapters in each book.[43] The first book is structured as a general introduction and table of contents of sixteen categories of knowledge.[43] Book two is about pramana (epistemology), book three is about prameya or the objects of knowledge, and the text discusses the nature of knowledge in remaining books.[43]

Reality is truth (prāma, foundation of correct knowledge), and what is true is so, irrespective of whether we know it is, or are aware of that truth.

– Akṣapada Gautama in Nyaya Sutra, Translated by Jeaneane D Fowler[47]

- Mimamsa Sutras - is the foundational text of the Mimamsa school of Hinduism, authored by Jaimini, and it emphasizes the early part of the Vedas, that is rituals and religious works as means to salvation.[48] The school emphasized precision in the selection of words, construction of sentences, developed rules for hermeneutics of language and any text, adopted and then refined principles of logic from the Nyaya school, and developed extensive rules for epistemology.[48] An atheistic school that supported external Vedic sacrifices and rituals, its Mimamsa Sutra contains twelve chapters with nearly 2700 sutras.[48]

- Dharma-sutras – of Āpastamba, Gautama, Baudhāyana, and Vāsiṣṭha

- Artha-sutras – the Niti Sutras of Chanakya and Somadeva are treatises on governance, law, economics, and politics. Versions of Chanakya Niti Sutras have been found in Sri Lanka and Myanmar.[49] The more comprehensive work of Chanakya, the Arthashastra is itself composed in many parts, in sutra style, with the first Sutra of the ancient book acknowledging that it is a compilation of Artha-knowledge from previous scholars.[50]

- Kama Sutra – an ancient Indian Sanskrit text on sexual and emotional fulfillment in life

- Moksha-sutras

- Shiva Sutras – fourteen verses that organize the phonemes of Sanskrit

- Narada Bhakti Sutra – a venerated Hindu sutra, reportedly spoken by the famous sage Narada

Buddhism

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

|

|

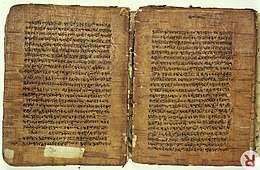

In Buddhism, a sutta or sutra is a part of the canonical literature. These early Buddhist sutras, unlike Hindu texts, are not aphoristic. On the contrary, they are most often quite lengthy. The Buddhist term sutta or sutra probably has roots in Sanskrit sūkta (su + ukta), "well spoken" from the belief that "all that was spoken by the Lord Buddha was well-spoken".[8] They share the character of sermons of "well spoken" wisdom with the Jaina sutras.

In Chinese, these are known as 經 (pinyin: jīng). These teachings are assembled in part of the Tripiṭaka which is called the Sutta Pitaka. There are many important or influential Mahayana texts, such as the Platform Sutra and the Lotus Sutra, that are called sutras despite being attributed to much later authors.

In Theravada Buddhism suttas comprise the second "basket" (pitaka) of the Pāli Canon. Rewata Dhamma and Bhikkhu Bodhi describe the Sutta pitaka as

The Sutta Pitaka, the second collection, brings together the Buddha's discourses spoken by him on various occasions during his active ministry of forty-five years.[51]

Jainism

| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

|

Jain prayers |

|

Ethics |

|

Major sects |

|

Texts |

|

Festivals

|

|

|

In the Jain tradition, sutras are an important genre of "fixed text", which used to be memorized.[52]

The Kalpa Sūtra is, for example, a Jain text that includes monastic rules,[53] as well as biographies of the Jain Tirthankaras.[54] Many sutras discuss all aspects of ascetic and lay life in Jainism. Various ancient sutras particularly from the early 1st millennium CE, for example, recommend devotional bhakti as an essential Jain practice.[9]

The surviving scriptures of Jaina tradition, such as the Acaranga Sutra (Agamas) exist in sutra format,[10] as is the Tattvartha Sutra – a Sanskrit text accepted by all four Jainism sects as the most authoritative philosophical text that completely summarizes the foundations of Jainism.[55][56]

See also

Notes

- Monier Williams, Sanskrit English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, Entry for sutra, page 1241

- M Winternitz (2010 Reprint), A History of Indian Literature, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0264-3, pages 249

- Gavin Flood (1996), An Introduction to Hinduism, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-43878-0, pages 54–55

- Max Muller, History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature, Oxford University Press, pages 108–113

- M Winternitz (2010 Reprint), A History of Indian Literature, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0264-3, pages 251–253

- Max Muller, History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature, Oxford University Press, page 74

- White, David Gordon (2014). The Yoga Sutra of Patanjali: A Biography. Princeton University Press. pp. 194–195. ISBN 978-0-691-14377-4.

- K. R. Norman (1997), A philological approach to Buddhism: the Bukkyo Dendo Kyokai Lectures 1994. (Buddhist Forum, Vol. v.)London: School of Oriental and African Studies,p. 104

- M. Whitney Kelting (2001). Singing to the Jinas: Jain Laywomen, Mandal Singing, and the Negotiations of Jain Devotion. Oxford University Press. pp. 111–112. ISBN 978-0-19-803211-3.

- Padmanabh S. Jaini (1991). Gender and Salvation: Jaina Debates on the Spiritual Liberation of Women. University of California Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-520-06820-9.

- Max Muller, History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature, Oxford University Press, pages 150–152

- MacGregor, Geddes (1989). Dictionary of Religion and Philosophy (1st ed.). New York: Paragon House. ISBN 1-55778-019-6.

- suci Archived 2017-01-09 at the Wayback Machine Sanskrit English Dictionary, Koeln University, Germany

- Max Muller, History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature, Oxford University Press, page 110–111

- Irving L. Finkel (2007). Ancient Board Games in Perspective: Papers from the 1990 British Museum Colloquium, with Additional Contributions. British Museum Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-7141-1153-7.

- Kale Pramod (1974). The Theatric Universe: (a Study of the Natyasastra). Popular. p. 8. ISBN 978-81-7154-118-8.

- Lewis Rowell (2015). Music and Musical Thought in Early India. University of Chicago Press. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-226-73034-9.

- व्याख्या Archived 2017-02-02 at the Wayback Machine, Sanskrit-English Dictionary, Koeln University, Germany

- Max Muller, History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature, Oxford University Press, page 199

- Max Muller, History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature, Oxford University Press, page 210

- Paul Deussen, The System of the Vedanta: According to Badarayana's Brahma Sutras and Shankara's Commentary thereon, Translator: Charles Johnston, ISBN 978-1-5191-1778-6, page 26

- Tubb, Gary A.; Emery B. Boose. "Scholastic Sanskrit, A Manual for Students". Indo-Iranian Journal. 51: 45–46. doi:10.1007/s10783-008-9085-y.

- Max Muller, History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature, Oxford University Press, pages 314–319

- Max Muller, History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature, Oxford University Press, pages 40–45, 71–77

- Arvind Sharma (2000), Classical Hindu Thought: An Introduction, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-564441-8, page 206

- Max Muller, History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature, Oxford University Press, page 70

- Max Muller, History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature, Oxford University Press, page 108

- Max Muller, History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature, Oxford University Press, pages 101–108

- Max Muller, History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature, Oxford University Press, pages 147

- Max Muller, History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature, Oxford University Press, pages 113–115

- Max Muller, History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature, Oxford University Press, pages 108–145

- Radhakrishna, Sarvepalli (1960). Brahma Sutra, The Philosophy of Spiritual Life. pp. 227–232.

George Adams (1993), The Structure and Meaning of Bādarāyaṇa's Brahma Sūtras, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0931-4, page 38 - Original Sanskrit: Brahma sutra Bhasya Adi Shankara, Archive 2

- NV Isaeva (1992), Shankara and Indian Philosophy, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-1281-7, page 35 with footnote 30

- James Lochtefeld, Brahman, The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 1: A–M, Rosen Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8239-3179-8, page 124

- Wujastyk, Dominik (2011), The Path to Liberation through Yogic Mindfulness in Early Ayurveda. In: David Gordon White (ed.), "Yoga in practice", Princeton University Press, p. 33

- White, David Gordon (2014). The Yoga Sutra of Patanjali: A Biography. Princeton University Press. p. xvi. ISBN 978-0-691-14377-4.

- Samkhya Pravachana Sutra NL Sinha, The Samkhya Philosophy, page i

- Kapila (James Robert Ballantyne, Translator, 1865), The Sāmkhya aphorisms of Kapila at Google Books, pages 156–157

- Max Muller et al. (1999 Reprint), Studies in Buddhism, Asian Educational Services, ISBN 81-206-1226-4, page 10 with footnote

- Klaus K. Klostermaier (2010), A Survey of Hinduism, Third Edition, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-7082-4, pages 334–335

- Jeaneane Fowler (2002), Perspectives of Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Hinduism, Sussex Academic Press, ISBN 978-1-898723-94-3, pages 98–107

- Jeaneane Fowler (2002), Perspectives of Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Hinduism, Sussex Academic Press, ISBN 978-1-898723-94-3, page 129

- B. K. Matilal "Perception. An Essay on Classical Indian Theories of Knowledge" (Oxford University Press, 1986), p. xiv.

- Ganganatha Jha (1999 Reprint), Nyaya Sutras of Gautama (4 vols.), Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1264-2

- SC Vidyabhushan and NL Sinha (1990), The Nyâya Sûtras of Gotama, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0748-8

- Jeaneane Fowler (2002), Perspectives of Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Hinduism, Sussex Academic Press, ISBN 978-1-898723-94-3, page 130

- Jeaneane Fowler (2002), Perspectives of Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Hinduism, Sussex Academic Press, ISBN 978-1-898723-94-3, pages 67–86

- SC Banerji (1989), A Companion to Sanskrit Literature, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0063-2, pages 586–587

- Thomas Trautman (2012), Arthashastra: The Science of Wealth, Penguin, ISBN 978-0-670-08527-9, pages 16–17, 61, 64, 75

- Dhamma, U Rewata; Bodhi, Bhikkhu (2000). A Comprehensive Manual of Abhidhamma. Buddhist Publication Society. pp. 1–2. ISBN 1-928706-02-9.

- M. Whitney Kelting (2001). Singing to the Jinas: Jain Laywomen, Mandal Singing, and the Negotiations of Jain Devotion. Oxford University Press. pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-0-19-803211-3.

- John Cort (2010). Framing the Jina: Narratives of Icons and Idols in Jain History. Oxford University Press. pp. 138–139. ISBN 978-0-19-973957-8.

- Jacobi, Hermann (1884). Max Müller (ed.). Kalpa Sutra, Jain Sutras Part I. Oxford University Press.

- K. V. Mardia (1990). The Scientific Foundations of Jainism. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 103. ISBN 978-81-208-0658-0.

Quote: Thus, there is a vast literature available but it seems that Tattvartha Sutra of Umasvati can be regarded as the main philosophical text of the religion and is recognized as authoritative by all Jains."

- Jaini, Padmanabh S. (1998). The Jaina path of purification. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 82. ISBN 81-208-1578-5.

References

- Arthur Anthony Macdonell (1900). . A History of Sanskrit Literature. New York: D. Appleton and company.

- Monier-Williams, Monier. (1899) A Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Delhi:Motilal Banarsidass. p. 1241

- Tubb, Gary A.; Boose, Emery R. (2007). Scholastic Sanskrit: A Handbook for Students. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-9753734-7-7.

External links

- SuttaCentral Public domain translations in multiple languages of suttas from the Pali Tipitaka and other collections.

- Buddhist Scriptures in Multiple Languages

- More Mahayana Sutras

- The Hindu Vedas, Upanishads, Puranas, and Vedanta Sacred-texts.com

- A Modern sutra

- Digital Sanskrit Buddhist Canon

- Ida B. Wells Memorial Sutra Library (Pali Suttas)

- Chinese and English Buddhist Sutras