Vanitas

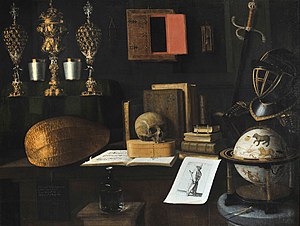

A vanitas is a symbolic work of art showing the transience of life, the futility of pleasure, and the certainty of death, often contrasting symbols of wealth and symbols of ephemerality and death. Best-known are vanitas still lifes, a common genre in Low countries of the 16th and 17th centuries; they have also been created at other times and in other media and genres.[1]

Etymology

The Latin noun vanitas (from the Latin adjective vanus 'empty') means 'emptiness', 'futility', or 'worthlessness', the traditional Christian view being that earthly goods and pursuits are transient and worthless.[2] It alludes to Ecclesiastes 1:2; 12:8, where vanitas translates the Hebrew word hevel, which also includes the concept of transitoriness.[3][4][5]

Themes

Vanitas themes were common in medieval funerary art, with most surviving examples in sculpture. By the 15th century, these could be extremely morbid and explicit, reflecting an increased obsession with death and decay also seen in the Ars moriendi, the Danse Macabre, and the overlapping motif of the Memento mori. From the Renaissance such motifs gradually became more indirect and, as the still-life genre became popular, found a home there. Paintings executed in the vanitas style were meant to remind viewers of the transience of life, the futility of pleasure, and the certainty of death. They also provided a moral justification for painting attractive objects.

Motifs

Common vanitas symbols include skulls, which are a reminder of the certainty of death; rotten fruit (decay); bubbles (the brevity of life and suddenness of death); smoke, watches, and hourglasses (the brevity of life); and musical instruments (brevity and the ephemeral nature of life). Fruit, flowers and butterflies can be interpreted in the same way, and a peeled lemon was, like life, attractive to look at but bitter to taste. Art historians debate how much, and how seriously, the vanitas theme is implied in still-life paintings without explicit imagery such as a skull. As in much moralistic genre painting, the enjoyment evoked by the sensuous depiction of the subject is in a certain conflict with the moralistic message.[6]

Composition of flowers is a less obvious style of Vanitas by Abraham Mignon in the National Museum, Warsaw. Barely visible amid vivid and perilous nature (snakes, poisonous mushrooms), a bird skeleton is a symbol of vanity and shortness of life.

Outside visual art

- The first movement in composer Robert Schumann's 5 Pieces in a Folk Style, for Cello and Piano, Op. 102 is entitled Vanitas vanitatum: Mit Humor.

- Vanitas vanitatum is the title of an oratorio written by an Italian Baroque composer Giacomo Carissimi (1604/1605 -1674).

- Composer Richard Barrett's Vanity, for orchestra, is greatly inspired by this movement.

- Vanitas is the seventh album by British Extreme Metal band Anaal Nathrakh.

- Vanitas is the name of a character from the Kingdom Hearts franchise.

- Vanitas is the name of one the two main characters from Vanitas no Carte

In modern times

- C. Allan Gilbert, All Is Vanity, drawing, 1892.

Life is Short - Don't Waste It Chasing Ghosts, by Chee Yong

Life is Short - Don't Waste It Chasing Ghosts, by Chee Yong - Jana Sterbak, Vanitas: Flesh Dress for an Albino Anorectic, artwork, 1987.

- Alexander de Cadenet, Skull Portraits, various subjects, 1996 – present.

- Philippe Pasqua, series of skulls, sculpture, 1990s – present.

- Damien Hirst, For the Love of God, sculpture (A diamond skull), 2007.

- Anne de Carbuccia, One Planet One Future, various subjects, 2013 – present.

- Vanitas

- Vanitas Still Life with Self-Portrait, Pieter Claesz, 1628

Vanitas painting, self-portrait c. 1610, most probably by Clara Peeters

Vanitas painting, self-portrait c. 1610, most probably by Clara Peeters Great Vanity, Sebastian Stoskopff, 1641

Great Vanity, Sebastian Stoskopff, 1641_by_Edward_Collier.jpg) Vanitas by Evert Collier, 1669

Vanitas by Evert Collier, 1669 Vanitas-Still Life, Maria van Oosterwijck (1630–1693)

Vanitas-Still Life, Maria van Oosterwijck (1630–1693) Vanitas, by Abraham Mignon

Vanitas, by Abraham Mignon Vanitas with bust, Joannes de Cordua (1630–1702)

Vanitas with bust, Joannes de Cordua (1630–1702) Allegory of Charles I of England and Henrietta of France in a Vanitas Still Life by Carstian Luyckx,

Allegory of Charles I of England and Henrietta of France in a Vanitas Still Life by Carstian Luyckx,- Adriaen van Utrecht - Vanitas, composition with flowers and skull

References

- Search for 'vanitas' at Harvard Art Museums

- Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary, s.v.

- Daniel C. Fredericks, Coping with Transience: Ecclesiastes on Brevity in Life, p. 15 and passim

- Ratcliffe, Susan (October 13, 2011). Oxford Treasury of Sayings and Quotations. Oxford: OUP. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-199-60912-3. ISBN 0-19960912-8.

- Delahunty, Andrew (October 23, 2008). From Bonbon to Cha-cha. Oxford Dictionary of Foreign Words and Phrases. Oxford: OUP. p. 360. ISBN 978-0-199-54369-4. ISBN 0-19954369-0.

- For more on this topic, see The Living Dead: Ecclesiastes through Art, exh. cat. edited by Corinna Ricasoli, Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh 2018, and the bibliography therein.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vanitas. |

| Look up vanitas in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Vanitas in the London National Gallery

- Vanités An exhibition at Musée Maillol, Paris

- vanitas (art) - Encyclopædia Britannica

- Vanitas concept expressed in ceramic compositions

- "An Exploration of Vanitas: The 17th Century and the Present", online exhibit at Google Arts & Culture