Summum bonum

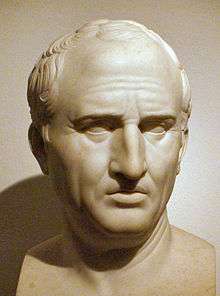

Summum bonum is a Latin expression meaning "the highest good", which was introduced by the Roman philosopher Cicero,[1][2] to correspond to the Idea of the Good in ancient Greek philosophy. The summum bonum is generally thought of as being an end in itself, and at the same time containing many other pursuits typified as Good by philosophers of the time.

The term was used in medieval philosophy. In the Thomist synthesis of Aristotelianism and Christianity, the highest good is usually defined as the life of the righteous and/or the life led in communion with God and according to God's precepts.[2] In Kantianism, it was used to describe the ultimate importance, the singular and overriding end which human beings ought to pursue.[3]

Plato and Aristotle

Plato's The Republic argued that, "In the world of knowledge the idea of good appears last of all, and is seen...to be the universal author of all things beautiful and right".[4] [5]Silent contemplation was the route to appreciation of the Idea of the Good.[6]

Aristotle in his Nicomachean Ethics accepted that the target of human activity, "Must be the 'Good', that is, the supreme good.", but challenged Plato's Idea of the Good with the pragmatic question: "Will one who has had a vision of the Idea itself become thereby a better doctor or general?".[7] However, arguably at least, Aristotle's concept of the unmoved mover owed much to Plato's Idea of the Good.[8]

Hellenic syncretism

Philo of Alexandria conflated the Old Testament God with the unmoved mover and the Idea of the Good.[9] Plotinus, the neoplatonic philosopher, built on Plato's Good for his concept of the supreme One, while Plutarch drew on Zoroastrianism to develop his eternal principle of good.[10]

Augustine of Hippo in his early writings offered the summum bonum as the highest human goal, but was later to identify it as a feature of the Christian God[11] in De natura boni (On the Nature of Good, c. 399). Augustine denies the positive existence of absolute evil, describing a world with God as the supreme good at the center, and defining different grades of evil as different stages of remoteness from that center.

Later developments

The summum bonum has continued to be a focus of attention in Western philosophy, secular and religious. Hegel replaced Plato's dialectical ascent to the Good by his own dialectical ascent to the Real.[12]

G. E. Moore placed the highest good in personal relations and the contemplation of beauty – even if not all his followers in the Bloomsbury Group may have appreciated what Clive Bell called his "all-important distinction between 'Good on the whole' and 'Good as a whole'".[13]

.jpg)

The doctrine of the highest good maintained by Immanuel Kant can be seen as the state in which an agent experiences happiness in proportion to their virtue.[14] It is the supreme end of the will, meaning that beyond the attainment of a good will, which is moral excellence signified by abiding by the categorical imperative and pure practical reason, the attainment of happiness in proportion to your moral excellence is the supreme, unconditional motivation of the will.[3] Furthermore, in virtue of the doctrine of the highest good, Kant postulates the existence of God and the eternal existence of rational agents, in order to reconcile three premises: (i) that agents are morally obligated to fully attain the highest good; (ii) that the object of an agent’s obligation must be possible; (iii) that an agent’s full realization of the highest good is not possible.[15]

Judgments

Judgments on the highest good have generally fallen into four categories:[2]

- Utilitarianism, when the highest good is identified with the maximum possible psychological happiness for the maximum number of people;

- Eudaemonism or virtue ethics, when the highest good is identified with flourishing;

- Rational deontologism, when the highest good is identified with virtue or duty;

- Rational eudaemonism, or tempered deontologism, when both virtue and happiness are combined in the highest good.

Notes

- De Finibus, Book II, 37ff

- Dinneen 1909.

- Basaglia, Federica (2016). "The Highest Good and the Notion of the Good as Object of Pure Practical Reason". In Höwing, Thomas (ed.). The Highest Good in Kant’s Philosophy. De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110369007-005. ISBN 978-3-11-036900-7.

- B. Jowett trans, The Essential Plato (1999) p. 269

- 517b,c (Stephanus)

- A. Kojeve, Introduction to the Reading of Hegel (1980) p. 108

- H, Tredennick revd, The Ethics of Aristotle (1976) p. 63 and p. 72

- Tredennick, p. 352

- J. Boardman ed., The Oxford History of the Classical World (1991) p. 703

- Boardman, p. 705-7

- J. McWilliam, Augustine (1992) p. 152-4

- Kojeve, p. 181-4

- Quoted in H. Lee, Virginia Woolf (1996) p. 253

- Tomasi, Gabriele (2016). "God, the Highest Good, and the Rationality of Faith: Reflections on Kant's Moral Proof of the Existence of God". In Höwing, Thomas (ed.). The Highest Good in Kant’s Philosophy. De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110369007-010. ISBN 978-3-11-036900-7.

- Silber, John R. (Oct 1959). "Kant's Conception of the Highest Good as Immanent and Transcendent". The Philosophical Review. 68 (4): 469. doi:10.2307/2182492. JSTOR 2182492.

- Attribution

![]()

External links

| Look up summum bonum in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 81.