Motivation

Motivation is the experience of desire or aversion (you want something, or want to avoid or escape something). As such, motivation has both an objective aspect (a goal or thing you aspire to) and an internal or subjective aspect (it is you that wants the thing or wants it to go away).

At minimum, motivation requires the biological substrate for physical sensations of pleasure and pain; animals can thus want or disdain specific objects based on sense perception and experience. Motivation goes on to include the capacity to form concepts and to reason, which allows humans to be able to surpass this minimum state, with a much greater possible range of desires and aversions. This much greater range is supported by the ability to choose one's own goals and values, combined with "time horizons" for value achievement that can perhaps encompass years, decades, or longer, and the ability to re-experience past events.[1] Some models treat as important the distinction between extrinsic and intrinsic motivation,[2][3] and motivation is an important topic in work,[4] organizational psychology, administrative organization, management,[5] as well as education.

The definition of motivation as experienced desires and aversions highlights the association of motivation with emotion. It is believed that emotions are automatic appraisals based on subconsciously stored values and beliefs about the object. To the extent that distinct emotions relate to specific subconscious appraisals (e.g., anger—injustice; guilt—violation of a moral standard; sadness—loss of a value; pride—the achievement of a moral ideal; love—valuing an object or person; joy—the attainment of an important value; envy—wanting the attainments of another, admiration—valuing the attainments of another, etc.), motivation theory involves specifying "content theories"—values that people find motivating—along with mechanisms by which they might attain these values (mastery, setting challenging goals, attending to required tasks, persistence, etc).

Changing motivation—either one's own or that of others (e.g., employees)—is another focus of motivation research (for example, altering how you choose to act on your emotions and re-programming them by modifying one's beliefs and values).[6]

Neuroscience

Motivation as a desire to perform an action is usually defined as having two parts: directional (such as directed towards a positive stimulus or away from a negative one), as well as the activated "seeking phase" and consummatory "liking phase". This type of motivation has neurobiological roots in the basal ganglia and mesolimbic (dopaminergic) pathways. Activated "seeking" behaviour, such as locomotor activity, is influenced by dopaminergic drugs, and microdialysis experiments reveal that dopamine is released during the anticipation of a reward.[7] The "wanting behaviour" associated with a rewarding stimulus can be increased by microinjections of dopamine and dopaminergic drugs in the dorsorostral nucleus accumbens and posterior ventral palladum. Opioid injections in this area produce pleasure; however, outside of these hedonic hotspots they create an increased desire.[8] Furthermore, depletion or inhibition of dopamine in neurons of the nucleus accumbens decreases appetitive but not consummatory behaviour. Dopamine is further implicated in motivation as administration of amphetamine increased the break point in a progressive ratio self-reinforcement schedule. That is, subjects were willing to go to greater lengths (e.g. press a lever more times) to obtain a reward.[9]

Psychological theories

Motivation can be conceived of as a cycle in which thoughts influence behaviours, drive performance affects thoughts, and the cycle begins again. Each stage of the cycle is composed of many dimensions including attitudes, beliefs, intentions, effort, and withdrawal, which can all affect the motivation that an individual experiences. Most psychological theories hold that motivation exists purely within the individual, but socio-cultural theories express motivation as an outcome of participation in actions and activities within the cultural context of social groups.[10]

Content theories

Theories articulating the content of motivation: what kinds of thing people find motivating are among the earliest theories in the history of motivation research. Because content theories focus on which categories of goal (needs) motivate people, content theories are related to need theories.

Maslow's hierarchy of needs

Content theory of human motivation includes both Abraham Maslow's hierarchy of needs and Herzberg's two-factor theory. Maslow's theory is one of the most widely discussed theories of motivation. Abraham Maslow believed that man is inherently good and argued that individuals possess a constantly growing inner drive that has great potential. The needs hierarchy system is a commonly used scheme for classifying human motives.[11]

The American motivation psychologist Abraham H. Maslow (1954) developed the hierarchy of needs consisting of five hierarchic classes. According to Maslow, people are motivated by unsatisfied needs. The needs, listed from basic (lowest-earliest) to most complex (highest-latest) are as follows:[12]

- Physiology (hunger, thirst, sleep, etc.)

- Safety/Security/Shelter/Health

- Social/Love/Friendship

- Self-esteem/Recognition/Achievement

- Self actualization/achievement of full potential

The basic requirements build upon the first step in the pyramid: physiology. If there are deficits on this level, all behavior will be oriented to satisfy this deficit. Essentially, if you have not slept or eaten adequately, you won't be interested in your self-esteem desires. Subsequently, we have the second level, which awakens a need for security. After securing those two levels, the motives shift to the social sphere, the third level. Psychological requirements comprise the fourth level, while the top of the hierarchy consists of self-realization and self-actualization.

Maslow's hierarchy of needs theory can be summarized as follows:

- Human beings have wants and desires which, when unsatisfied, may influence behavior.

- Differing levels of importance to human life are reflected in a hierarchical structure of needs.

- Needs at higher levels in the hierarchy are held in abeyance until lower level needs are at least minimally satisfied.

- Needs at higher levels of the hierarchy are associated with individuality, humanness and psychological health.

Sex, Hedonism, and Evolution

One of the first influential figures to discuss the topic of hedonism was Socrates, and he did so around 470–399 BCE in ancient Greece. Hedonism, as Socrates described it, is the motivation wherein a person will behave in a manner that will maximize pleasure and minimize pain. The only instance in which a person will behave in a manner that results in more pain than pleasure is when the knowledge of the effects of the behavior is lacking. Sex is one of the pleasures people pursue.[13][14]

Sex is on the first level of Maslow's hierarchy of needs. It is a necessary physiological need like air, warmth, or sleep, and if the body lacks it will not function optimally. Without the orgasm that comes with sex, a person will experience “pain,” and as hedonism would predict, a person will minimize this pain by pursuing sex. That being said, sex as a basic need is different from the need for sexual intimacy, which is located on the third level in Maslow's hierarchy.[13]

There are multiple theories for why sex is a strong motivation, and many fall under the theory of evolution. On an evolutionary level, the motivation for sex likely has to do with a species’ ability to reproduce. Species that reproduce more, survive and pass on their genes. Therefore, species have sexual desire that leads to sexual intercourse as a means to create more offspring. Without this innate motivation, a species may determine that attaining intercourse is too costly in terms of effort, energy, and danger.[13][15]

In addition to sexual desire, the motivation for romantic love runs parallel in having an evolutionary function for the survival of a species. On an emotional level, romantic love satiates a psychological need for belonging. Therefore, this is another hedonistic pursuit of pleasure. From the evolutionary perspective, romantic love creates bonds with the parents of offspring. This bond will make it so that the parents will stay together and take care and protect the offspring until it is independent. By rearing the child together, it increases the chances that the offspring will survive and pass on its genes itself, therefore continuing the survival of the species. Without the romantic love bond, the male will pursue satiation of his sexual desire with as many mates as possible, leaving behind the female to rear the offspring by herself. Child rearing with one parent is more difficult and provides less assurance that the offspring survives than with two parents. Romantic love therefore solves the commitment problem of parents needing to be together; individuals that are loyal and faithful to one another will have mutual survival benefits.[13][16][17]

Additionally, under the umbrella of evolution, is Darwin's term sexual selection. This refers to how the female selects the male for reproduction. The male is motivated to attain sex because of all the aforementioned reasons, but how he attains it can vary based on his qualities. For some females, they are motivated by the will to survive mostly, and will prefer a mate that can physically defend her, or financially provide for her (among humans). Some females are more attracted to charm, as it is an indicator of being a good loyal lover that will in turn make for a dependable child rearing partner. Altogether, sex is a hedonistic pleasure seeking behavior that satiates physical and psychological needs and is instinctively guided by principles of evolution.[13][18]

Herzberg's two-factor theory

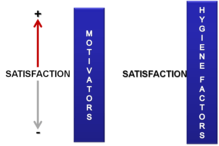

Frederick Herzberg's two-factor theory concludes that certain factors in the workplace result in job satisfaction (motivators), while others (hygiene factors), if absent, lead to dissatisfaction but are not related to satisfaction. The name hygiene factors is used because, like hygiene, the presence will not improve health, but absence can cause health deterioration.

The factors that motivate people can change over their lifetime. Some claimed motivating factors (satisfiers) were: Achievement, recognition, work itself, responsibility, advancement, and growth. Some hygiene factors (dissatisfiers) were: company policy, supervision, working conditions, interpersonal relations, salary, status, job security, and personal life.[19]

Alderfer's ERG theory

Alderfer, building on Maslow's hierarchy of needs, posited that needs identified by Maslow exist in three groups of core needs — existence, relatedness, and growth, hence the label: ERG theory. The existence group is concerned with providing our basic material existence requirements. They include the items that Maslow considered to be physiological and safety needs. The second group of needs are those of relatedness- the desire we have for maintaining important personal relationships. These social and status desires require interaction with others if they are to be satisfied, and they align with Maslow's social need and the external component of Maslow's esteem classification. Finally, Alderfer isolates growth needs as an intrinsic desire for personal development. All these needs should be fulfilled to greater wholeness as a human being.[20]

Self-determination theory

Since the early 1970s Deci[21] and Ryan have developed and tested their self-determination theory (SDT). SDT identifies three innate needs that, if satisfied, allow optimal function and growth: competence,[22][23] relatedness,[24] and autonomy.[25][26] These three psychological needs are suggested to be essential for psychological health and well-being and to motivate behaviour.[27] There are three essential elements to the theory:[28]

- Humans are inherently proactive with their potential and mastering their inner forces (such as drive and emotions).

- Humans have an inherent tendency towards growth, development and integrated functioning.

- Optimal development and actions are inherent in humans but they do not happen automatically.

Within Self-Determination Theory, Deci & Ryan[29] distinguish between four different types of extrinsic motivation, differing in their levels of perceived autonomy:

- External regulation: This is the least autonomous of the four and is determined by external punishment or reward.

- Introjected regulation: This form of external motivation arises when the individual has somewhat internalized regulations but does not fully accept them as their own. They may comply for self-esteem reasons or social acceptability - essentially internal reasons but externally driven.

- Identified regulation: This more autonomously driven - when the individual consciously perceives the actions as valuable.

- Integrated regulation: This is the most autonomous form of motivation and the action has been internalized and is aligned with the individual's values, beliefs and is perceived as necessary for their wellbeing. However this is still classified as extrinsic motivation as it is still driven by external processes and not by inherent enjoyment for the task itself.

"16 basic desires" theory

Starting from studies involving more than 6,000 people, Reiss proposed that 16 basic desires guide nearly all human behavior.[30] In this model the basic desires that motivate our actions and define our personalities are:

- Acceptance, the need for approval

- Curiosity, the need to learn

- Eating, the need for food

- Family, the need to raise children

- Honor, the need to be loyal to the traditional values of one's clan/ethnic group

- Idealism, the need for social justice

- Independence, the need for individuality

- Order, the need for organized, stable, predictable environments

- Physical activity, the need for exercise

- Power, the need for influence of will

- Romance, the need for sex and for beauty

- Saving, the need to collect

- Social contact, the need for friends (peer relationships)

- Social status, the need for social standing/importance

- Tranquility, the need to be safe

- Vengeance, the need to strike back and to compete

Natural theories

The natural system assumes that people have higher order needs, which contrasts with the rational theory that suggests people dislike work and only respond to rewards and punishment.[31] According to McGregor's Theory Y, human behaviour is based on satisfying a hierarchy of needs: physiological, safety, social, ego, and self-fulfillment.[32]

Physiological needs are the lowest and most important level. These fundamental requirements include food, rest, shelter, and exercise. After physiological needs are satisfied, employees can focus on safety needs, which include “protection against danger, threat, deprivation.”[32] However, if management makes arbitrary or biased employment decisions, then an employee's safety needs are unfulfilled.

The next set of needs is social, which refers to the desire for acceptance, affiliation, reciprocal friendships and love. As such, the natural system of management assumes that close-knit work teams are productive. Accordingly, if an employee's social needs are unmet, then he will act disobediently.[32]

There are two types of egoistic needs, the second-highest order of needs. The first type refers to one's self-esteem, which encompasses self-confidence, independence, achievement, competence, and knowledge. The second type of needs deals with reputation, status, recognition, and respect from colleagues.[32] Egoistic needs are much more difficult to satisfy.

The highest order of needs is for self-fulfillment, including recognition of one's full potential, areas for self-improvement, and the opportunity for creativity. This differs from the rational system, which assumes that people prefer routine and security to creativity.[31] Unlike the rational management system, which assumes that humans don't care about these higher order needs, the natural system is based on these needs as a means for motivation.

The author of the reductionist motivation model is Sigmund Freud. According to the model, physiological needs raise tension, thereby forcing an individual to seek an outlet by satisfying those needs Ziegler, Daniel (1992). Personality Theories: Basic Assumptions, Research, and Applications.

Self-management through teamwork

To successfully manage and motivate employees, the natural system posits that being part of a group is necessary.[33] Because of structural changes in social order, the workplace is more fluid and adaptive according to Mayo. As a result, individual employees have lost their sense of stability and security, which can be provided by a membership in a group. However, if teams continuously change within jobs, then employees feel anxious, empty, and irrational and become harder to work with.[33] The innate desire for lasting human association and management “is not related to single workers, but always to working groups.”[33] In groups, employees will self-manage and form relevant customs, duties, and traditions.

Wage incentives

Humans are motivated by additional factors besides wage incentives.[34] Unlike the rational theory of motivation, people are not driven toward economic interests per the natural system. For instance, the straight piecework system pays employees based on each unit of their output. Based on studies such as the Bank Wiring Observation Room, using a piece rate incentive system does not lead to higher production.[34] Employees actually set upper limits on each person's daily output. These actions stand “in direct opposition to the ideas underlying their system of financial incentive, which countenanced no upper limit to performance other than physical capacity.”[34] Therefore, as opposed to the rational system that depends on economic rewards and punishments, the natural system of management assumes that humans are also motivated by non-economic factors.

Autonomy: increased motivation for autonomous tasks

Employees seek autonomy and responsibility in their work, contrary to assumptions of the rational theory of management. Because supervisors have direct authority over employees, they must ensure that the employee's actions are in line with the standards of efficient conduct.[34] This creates a sense of restriction on the employee and these constraints are viewed as “annoying and seemingly functioned only as subordinating or differentiating mechanisms."[34] Accordingly, the natural management system assumes that employees prefer autonomy and responsibility on the job and dislike arbitrary rules and overwhelming supervision. An individual's motivation to complete a task is increased when this task is autonomous. When the motivation to complete a task comes from an "external pressure" that pressure then "undermines" a person's motivation, and as a result decreases a persons desire to complete the task.[35]

Rational motivations

The idea that human beings are rational and human behaviour is guided by reason is an old one. However, recent research (on satisfying for example) has significantly undermined the idea of homo economicus or of perfect rationality in favour of a more bounded rationality. The field of behavioural economics is particularly concerned with the limits of rationality in economic agents.[36]

Incentive theories: intrinsic and extrinsic motivation

Motivation can be divided into two different theories known as intrinsic (internal or inherent) motivation and extrinsic (external) motivation.

Intrinsic motivation

Intrinsic motivation has been studied since the early 1970s. Intrinsic motivation is a behavior that is driven by satisfying internal rewards. For example, an athlete may enjoy playing football for the experience, rather than for an award.[2] It is an interest or enjoyment in the task itself, and exists within the individual rather than relying on external pressures or a desire for consideration. Deci (1971) explained that some activities provide their own inherent reward, meaning certain activities are not dependent on external rewards.[37] The phenomenon of intrinsic motivation was first acknowledged within experimental studies of animal behaviour. In these studies, it was evident that the organisms would engage in playful and curiosity-driven behaviours in the absence of reward. Intrinsic motivation is a natural motivational tendency and is a critical element in cognitive, social, and physical development.[38] The two necessary elements for intrinsic motivation are self-determination and an increase in perceived competence.[39] In short, the cause of the behaviour must be internal, known as internal locus of causality, and the individual who engages in the behaviour must perceive that the task increases their competence.[38] According to various research reported by Deci's published findings in 1971, and 1972, tangible rewards could actually undermine the intrinsic motivation of college students. However, these studies didn't just affect college students, Kruglanski, Friedman and Zeevi (1971) repeated this study and found that symbolic and material rewards can undermine not just high school students, but preschool students as well.

Students who are intrinsically motivated are more likely to engage in the task willingly as well as work to improve their skills, which will increase their capabilities.[40] Students are likely to be intrinsically motivated if they...

- attribute their educational results to factors under their own control, also known as autonomy or locus of control

- believe they have the skills to be effective agents in reaching their desired goals, also known as self-efficacy beliefs

- are interested in mastering a topic, not just in achieving good grades

- don't act from pressure, but from interest

An example of intrinsic motivation is when an employee becomes an IT professional because he or she wants to learn about how computer users interact with computer networks. The employee has the intrinsic motivation to gain more knowledge, and will continue to want to learn even in the face of failure.[41] Art for art's sake is an example of intrinsic motivation in the domain of art.

Traditionally, researchers thought of motivations to use computer systems to be primarily driven by extrinsic purposes; however, many modern systems have their use driven primarily by intrinsic motivations.[42] Examples of such systems used primarily to fulfill users' intrinsic motivations, include on-line gaming, virtual worlds, online shopping,[43] learning/education, online dating, digital music repositories, social networking, online pornography, gamified systems, and general gamification. Even traditional management information systems (e.g., ERP, CRM) are being 'gamified' such that both extrinsic and intrinsic motivations must increasingly be considered. Deci's findings didn't come without controversy. Articles stretching over the span of 25 years from the perspective of behavioral theory argue there isn't enough evidence to explain intrinsic motivation and this theory would inhibit "scientific progress." As stated above, we now can see technology such as various forms of computer systems are highly intrinsic.[37]

Not only can intrinsic motivation be used in a personal setting, but it can also be implemented and utilized in a social environment. Instead of attaining mature desires, such as those presented above via internet which can be attained on one's own, intrinsic motivation can be used to assist extrinsic motivation to attain a goal. For example, Eli, a 4-year-old with autism, wants to achieve the goal of playing with a toy train.[44] To get the toy, he must first communicate to his therapist that he wants it. His desire to play is strong enough to be considered intrinsic motivation because it is a natural feeling, and his desire to communicate with his therapist to get the train can be considered extrinsic motivation because the outside object is a reward (see incentive theory). Communicating with the therapist is the first, slightly more challenging goal that stands in the way of achieving his larger goal of playing with the train. Achieving these goals in attainable pieces is also known as the goal-setting theory. The three elements of goal-setting (STD) are Specific, Time-bound, and Difficult. Specifically goals should be set in the 90th percentile of difficulty.[10]

Intrinsic motivation comes from one's desire to achieve or attain a goal.[2] Pursuing challenges and goals come easier and more enjoyable when one is intrinsically motivated to complete a certain objective because the individual is more interested in learning, rather than achieving the goal.[3] Edward Deci and Richard Ryan's theory of intrinsic motivation is essentially examining the conditions that “elicit and sustain” this phenomenon.[45] Deci and Ryan coin the term “cognitive evaluation theory which concentrates on the needs of competence and autonomy. The CET essentially states that social-contextual events like feedback and reinforcement can cause feelings of competence and therefore increase intrinsic motivation. However, feelings of competence will not increase intrinsic motivation if there is no sense of autonomy. In situations where choices, feelings, and opportunities are present, intrinsic motivation is increased because people feel a greater sense of autonomy.[45] Offering people choices, responding to their feelings, and opportunities for self-direction have been reported to enhance intrinsic motivation via increased autonomy (Deci & Ryan, 1985).[46][47]

An advantage (relative to extrinsic motivation) is that intrinsic motivators can be long-lasting, self-sustaining, and satisfying.[3] For this reason, efforts in education sometimes attempt to modify intrinsic motivation with the goal of promoting future student learning performance, creativity, and learning via long-term modifications in interests.[2] Intrinsic motivators are suggested to involve increased feelings of reward and thus may support subjective well-being. By contrast, intrinsic motivation has been found to be hard to modify, and attempts to recruit existing intrinsic motivators require a non-trivially difficult individualized approach, identifying and making relevant the different motivators of needed to motivate different students[2], possibly requiring additional skills and intrinsic motivation from the instructor.[48]

Extrinsic motivation

Extrinsic motivation comes from influences outside of the individual. In extrinsic motivation, the harder question to answer is where do people get the motivation to carry out and continue to push with persistence. Usually extrinsic motivation is used to attain outcomes that a person wouldn't get from intrinsic motivation.[3] Common extrinsic motivations are rewards (for example money or grades) for showing the desired behaviour, and the threat of punishment following misbehaviour. Competition is an extrinsic motivator because it encourages the performer to win and to beat others, not simply to enjoy the intrinsic rewards of the activity. A cheering crowd and the desire to win a trophy are also extrinsic incentives.[49] For example, if an individual plays the sport tennis to receive an award, that would be extrinsic motivation. VS. The individual play because he or she enjoys the game, that would be intrinsic motivation.[2]

The most simple distinction between extrinsic and intrinsic motivation is the type of reasons or goals that lead to an action. While intrinsic motivation refers to doing something because it is inherently interesting or enjoyable and satisfying, extrinsic motivation, refers to doing something because it leads to a separable outcome.[3] Extrinsic motivation thus contrasts with intrinsic motivation, which is doing an activity simply for the enjoyment of the activity itself, instead of for its instrumental value.[2]

Social psychological research has indicated that extrinsic rewards can lead to overjustification and a subsequent reduction in intrinsic motivation. In one study demonstrating this effect, children who expected to be (and were) rewarded with a ribbon and a gold star for drawing pictures spent less time playing with the drawing materials in subsequent observations than children who were assigned to an unexpected reward condition.[50] This shows how if an individual expects an award they don't care about the outcome. VS. if an individual doesn't expect a reward they will care more about the task.[3]However, another study showed that third graders who were rewarded with a book showed more reading behaviour in the future, implying that some rewards do not undermine intrinsic motivation.[51] While the provision of extrinsic rewards might reduce the desirability of an activity, the use of extrinsic constraints, such as the threat of punishment, against performing an activity has actually been found to increase one's intrinsic interest in that activity. In one study, when children were given mild threats against playing with an attractive toy, it was found that the threat actually served to increase the child's interest in the toy, which was previously undesirable to the child in the absence of threat.[52]

Advantages of extrinsic motivators are that they easily promote motivation to work and persist to goal completion. Rewards are tangible and beneficial.[3] A disadvantage for extrinsic motivators relative to internal is that work does not persist long once external rewards are removed. As the task is completed for the reward quality of work may need to be monitored[2], and it has been suggested that extrinsic motivators may diminish in value over time.[3]

Flow theory

Flow theory refers to desirable subjective state a person experiences when completely involved in some challenging activity that matches the individual skill.[53]

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi described Flow theory as "A state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter; the experience is so enjoyable that people will continue to do it even at great cost, for the sheer sake of doing it."[54]

The idea of flow theory as first conceptualized by Csikszentmihalyi. Flow in the context of motivation can be seen as an activity that is not too hard, frustrating or madding, or too easy boring and done too fast. If one has achieved perfect flow, then the activity has reached maximum potential.[54]

Flow is part of something called positive psychology of the psychology of happiness. Positive psychology looks into what makes a person happy. Flow can be considered as achieving happiness or at the least positive feelings. A study that was published in the journal Emotion looked at flow experienced in college students playing Tetris. The students that they were being evaluated on looks then told to wait and play Tetris. There were three categories; Easy, normal, and hard. The students that played Tetris on normal level experienced flow and were less stressed about the evaluation.[55]

Csikszentmihalyi describes 8 characteristics of flow as a complete concentration on the task, clarity of goals and reward in mind and immediate feedback, transformation of time (speeding up/slowing down of time), the experience is intrinsically rewarding, effortlessness and ease, there is a balance between challenge and skills, actions and awareness are merged, losing self-conscious rumination, there is a feeling of control over the task.[54]

The activity no longer becomes something seen as a means to an end and it becomes something an individual wants to do. This can be seen as someone who likes to run for the sheer joy of running and not because they need to do it for exercise or because they want to brag about it. Peak flow can be different for each person. It could take an individual years to reach flow or only moments. If an individual becomes too good at an activity they can become bored. If the challenge becomes too hard then the individual could become discouraged and want to quit.[56]

Behaviorist theories

While many theories on motivation have a mentalistic perspective, behaviorists focus only on observable behaviour and theories founded on experimental evidence. In the view of behaviorism, motivation is understood as a question about what factors cause, prevent, or withhold various behaviours, while the question of, for instance, conscious motives would be ignored. Where others would speculate about such things as values, drives, or needs, that may not be observed directly, behaviorists are interested in the observable variables that affect the type, intensity, frequency and duration of observable behaviour. Through the basic research of such scientists as Pavlov, Watson and Skinner, several basic mechanisms that govern behaviour have been identified. The most important of these are classical conditioning and operant conditioning.

Classical and operant conditioning

In classical (or respondent) conditioning, behaviour is understood as responses triggered by certain environmental or physical stimuli. They can be unconditioned, such as in-born reflexes, or learned through the pairing of an unconditioned stimulus with a different stimulus, which then becomes a conditioned stimulus. In relation to motivation, classical conditioning might be seen as one explanation as to why an individual performs certain responses and behaviors in certain situations.[57][58] For instance, a dentist might wonder why a patient does not seem motivated to show up for an appointment, with the explanation being that the patient has associated the dentist (conditioned stimulus) with the pain (unconditioned stimulus) that elicits a fear response (conditioned response), leading to the patient being reluctant to visit the dentist.

In operant conditioning, the type and frequency of behaviour is determined mainly by its consequences. If a certain behaviour, in the presence of a certain stimulus, is followed by a desirable consequence (a reinforcer), the emitted behaviour will increase in frequency in the future, in the presence of the stimulus that preceded the behaviour (or a similar one). Conversely, if the behaviour is followed by something undesirable (a punisher), the behaviour is less likely to occur in the presence of the stimulus. In a similar manner, removal of a stimulus directly following the behaviour might either increase or decrease the frequency of that behaviour in the future (negative reinforcement or punishment).[57][58] For instance, a student that gained praise and a good grade after turning in a paper, might seem more motivated in writing papers in the future (positive reinforcement); if the same student put in a lot of work on a task without getting any praise for it, he or she might seem less motivated to do school work in the future (negative punishment). If a student starts to cause trouble in class gets punished with something he or she dislikes, such as detention (positive punishment), that behaviour would decrease in the future. The student might seem more motivated to behave in class, presumably in order to avoid further detention (negative reinforcement).

The strength of reinforcement or punishment is dependent on schedule and timing. A reinforcer or punisher affects the future frequency of a behaviour most strongly if it occurs within seconds of the behaviour. A behaviour that is reinforced intermittently, at unpredictable intervals, will be more robust and persistent, compared to one that is reinforced every time the behaviour is performed.[57][58] For example, if the misbehaving student in the above example was punished a week after the troublesome behaviour, that might not affect future behaviour.

In addition to these basic principles, environmental stimuli also affect behavior. Behaviour is punished or reinforced in the context of whatever stimuli were present just before the behaviour was performed, which means that a particular behaviour might not be affected in every environmental context, or situation, after it is punished or reinforced in one specific context.[57][58] A lack of praise for school-related behaviour might, for instance, not decrease after-school sports-related behaviour that is usually reinforced by praise.

The various mechanisms of operant conditioning may be used to understand the motivation for various behaviours by examining what happens just after the behaviour (the consequence), in what context the behaviour is performed or not performed (the antecedent), and under what circumstances (motivating operators).[57][58]

Incentive motivation

Incentive theory is a specific theory of motivation, derived partly from behaviorist principles of reinforcement, which concerns an incentive or motive to do something. The most common incentive would be a compensation. Compensation can be tangible or intangible, It helps in motivating the employees in their corporate life, students in academics and inspire to do more and more to achieve profitability in every field. Studies show that if the person receives the reward immediately, the effect is greater, and decreases as delay lengthens. Repetitive action-reward combination can cause the action to become a habit

"Reinforcers and reinforcement principles of behaviour differ from the hypothetical construct of reward." A reinforcer is anything that follows an action, with the intentions that the action will now occur more frequently. From this perspective, the concept of distinguishing between intrinsic and extrinsic forces is irrelevant.

Incentive theory in psychology treats motivation and behaviour of the individual as they are influenced by beliefs, such as engaging in activities that are expected to be profitable. Incentive theory is promoted by behavioral psychologists, such as B.F. Skinner. Incentive theory is especially supported by Skinner in his philosophy of Radical behaviorism, meaning that a person's actions always have social ramifications: and if actions are positively received people are more likely to act in this manner, or if negatively received people are less likely to act in this manner.

Incentive theory distinguishes itself from other motivation theories, such as drive theory, in the direction of the motivation. In incentive theory, stimuli "attract" a person towards them, and push them towards the stimulus. In terms of behaviorism, incentive theory involves positive reinforcement: the reinforcing stimulus has been conditioned to make the person happier. As opposed to in drive theory, which involves negative reinforcement: a stimulus has been associated with the removal of the punishment—the lack of homeostasis in the body. For example, a person has come to know that if they eat when hungry, it will eliminate that negative feeling of hunger, or if they drink when thirsty, it will eliminate that negative feeling of thirst.[59]

Motivating operations

Motivating operations, MOs, relate to the field of motivation in that they help improve understanding aspects of behaviour that are not covered by operant conditioning. In operant conditioning, the function of the reinforcer is to influence future behavior. The presence of a stimulus believed to function as a reinforcer does not according to this terminology explain the current behaviour of an organism – only previous instances of reinforcement of that behavior (in the same or similar situations) do. Through the behavior-altering effect of MOs, it is possible to affect current behaviour of an individual, giving another piece of the puzzle of motivation.

Motivating operations are factors that affect learned behaviour in a certain context. MOs have two effects: a value-altering effect, which increases or decreases the efficiency of a reinforcer, and a behavior-altering effect, which modifies learned behaviour that has previously been punished or reinforced by a particular stimulus.[57]

When a motivating operation causes an increase in the effectiveness of a reinforcer, or amplifies a learned behaviour in some way (such as increasing frequency, intensity, duration or speed of the behaviour), it functions as an establishing operation, EO. A common example of this would be food deprivation, which functions as an EO in relation to food: the food-deprived organism will perform behaviours previously related to the acquisition of food more intensely, frequently, longer, or faster in the presence of food, and those behaviours would be especially strongly reinforced.[57] For instance, a fast-food worker earning minimal wage, forced to work more than one job to make ends meet, would be highly motivated by a pay raise, because of the current deprivation of money (a conditioned establishing operation). The worker would work hard to try to achieve the raise, and getting the raise would function as an especially strong reinforcer of work behaviour.

Conversely, a motivating operation that causes a decrease in the effectiveness of a reinforcer, or diminishes a learned behaviour related to the reinforcer, functions as an abolishing operation, AO. Again using the example of food, satiation of food prior to the presentation of a food stimulus would produce a decrease on food-related behaviours, and diminish or completely abolish the reinforcing effect of acquiring and ingesting the food.[57] Consider the board of a large investment bank, concerned with a too small profit margin, deciding to give the CEO a new incentive package in order to motivate him to increase firm profits. If the CEO already has a lot of money, the incentive package might not be a very good way to motivate him, because he would be satiated on money. Getting even more money wouldn't be a strong reinforcer for profit-increasing behaviour, and wouldn't elicit increased intensity, frequency or duration of profit-increasing behaviour.

Motivation and psychotherapy

Motivation lies at the core of many behaviorist approaches to psychological treatment. A person with autism-spectrum disorder is seen as lacking motivation to perform socially relevant behaviours – social stimuli are not as reinforcing for people with autism compared to other people. Depression is understood as a lack of reinforcement (especially positive reinforcement) leading to extinction of behavior in the depressed individual. A patient with specific phobia is not motivated to seek out the phobic stimulus because it acts as a punisher, and is over-motivated to avoid it (negative reinforcement). In accordance, therapies have been designed to address these problems, such as EIBI and CBT for major depression and specific phobia.

Socio-cultural theory

Sociocultural theory (also known as Social Motivation) emphasizes impact of activity and actions mediated through social interaction, and within social contexts. Sociocultural theory represents a shift from traditional theories of motivation, which view the individual's innate drives or mechanistic operand learning as primary determinants of motivation. Critical elements to socio-cultural theory applied to motivation include, but are not limited to, the role of social interactions and the contributions from culturally-based knowledge and practice.[10] Sociocultural theory extends the social aspects of Cognitive Evaluation Theory, which espouses the important role of positive feedback from others during action,[3] but requires the individual as the internal locus of causality. Sociocultural theory predicts that motivation has an external locus of causality, and is socially distributed among the social group.[10]

Motivation can develop through an individual's involvement within their cultural group. Personal motivation often comes from activities a person believes to be central to the everyday occurrences in their community.[60] An example of socio-cultural theory would be social settings where people work together to solve collective problems. Although individuals will have internalized goals, they will also develop internalized goals of others, as well as new interests and goals collectively with those that they feel socially connected to.[61] Oftentimes, it is believed that all cultural groups are motivated in the same way. However, motivation can come from different child-rearing practices and cultural behaviors that greatly vary between cultural groups.

In some indigenous cultures, collaboration between children and adults in community and household tasks is seen as very important[62] A child from an indigenous community may spend a great deal of their time alongside family and community members doing different tasks and chores that benefit the community. After having seen the benefits of collaboration and work, and also having the opportunity to be included, the child will be intrinsically motivated to participate in similar tasks. In this example, because the adults in the community do not impose the tasks upon the children, the children therefore feel self-motivated and a desire to participate and learn through the task.[63] As a result of the community values that surround the child, their source of motivation may vary from a different community with different values.

In more Westernized communities, where segregation between adults and children participating in work related task is a common practice. As a result of this, these adolescents demonstrate less internalized motivation to do things within their environment than their parents. However, when the motivation to participate in activities is a prominent belief within the family, the adolescents autonomy is significantly higher. This therefore demonstrating that when collaboration and non-segregative tasks are norms within a child's upbringing, their internal motivation to participate in community tasks increases.[64] When given opportunities to work collaboratively with adults on shared tasks during childhood, children will therefore become more intrinsically motivated through adulthood.[65]

Social motivation is tied to one's activity in a group. It cannot form from a single mind alone. For example, bowling alone is naught but the dull act of throwing a ball into pins, and so people are much less likely to smile during the activity alone, even upon getting a strike because their satisfaction or dissatisfaction does not need to be communicated, and so it is internalized. However, when with a group, people are more inclined to smile regardless of their results because it acts as a positive communication that is beneficial for pleasurable interaction and teamwork.[61] Thus the act of bowling becomes a social activity as opposed to a dull action because it becomes an exercise in interaction, competition, team building, and sportsmanship. It is because of this phenomenon that studies have shown that people are more intrigued in performing mundane activities so long as there is company because it provides the opportunity to interact in one way or another, be it for bonding, amusement, collaboration, or alternative perspectives.[61] Examples of activities that may one may not be motivated to do alone but could be done with others for social benefit are things such as throwing and catching a baseball with a friend, making funny faces with children, building a treehouse, and performing a debate.

Push and pull

Push

Push motivations are those where people push themselves towards their goals or to achieve something, such as the desire for escape, rest and relaxation, prestige, health and fitness, adventure, and social interaction.[66]

However, with push motivation it's also easy to get discouraged when there are obstacles present in the path of achievement. Push motivation acts as a willpower and people's willpower is only as strong as the desire behind the willpower.[67]

Additionally, a study has been conducted on social networking and its push and pull effects. One thing that is mentioned is "Regret and dissatisfaction correspond to push factors because regret and dissatisfaction are the negative factors that compel users to leave their current service provider."[68] So from reading this, we now know that Push motivations can also be a negative force. In this case, that negative force is regret and dissatisfaction.

Pull

Pull motivation is the opposite of push. It is a type of motivation that is much stronger. "Some of the factors are those that emerge as a result of the attractiveness of a destination as it is perceived by those with the propensity to travel. They include both tangible resources, such as beaches, recreation facilities, and cultural attractions, and traveler's perceptions and expectation, such as novelty, benefit expectation, and marketing image."[66] Pull motivation can be seen as the desire to achieve a goal so badly that it seems that the goal is pulling us toward it. That is why pull motivation is stronger than push motivation. It is easier to be drawn to something rather than to push yourself for something you desire. It can also be an alternative force when compared to negative force. From the same study as previously mentioned, "Regret and dissatisfaction with an existing SNS service provider may trigger a heightened interest toward switching service providers, but such a motive will likely translate into reality in the presence of a good alternative. Therefore, alternative attractiveness can moderate the effects of regret and dissatisfaction with switching intention"[68] And so, pull motivation can be an attracting desire when negative influences come into the picture.

Self-control

The self-control aspect of motivation is increasingly considered to be a subset of emotional intelligence;[69] it is suggested that although a person may be classed as highly intelligent (as measured by many traditional intelligence tests), they may remain unmotivated to pursue intellectual endeavours. Vroom's "expectancy theory" provides an account of when people may decide to exert self-control in pursuit of a particular goal.

Drives

A drive or desire can be described as a deficiency or need that activates behavior that is aimed at a goal or an incentive.[70] These drives are thought to originate within the individual and may not require external stimuli to encourage the behavior. Basic drives could be sparked by deficiencies such as hunger, which motivates a person to seek food whereas more subtle drives might be the desire for praise and approval, which motivates a person to behave in a manner pleasing to others.

Another basic drive is the sexual drive which like food motivates us because it is essential to our survival.[71] The desire for sex is wired deep into the brain of all human beings as glands secrete hormones that travel through the blood to the brain and stimulates the onset of sexual desire.[71] The hormone involved in the initial onset of sexual desire is called Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA).[71] The hormonal basis of both men and women's sex drives is testosterone.[71] Men naturally have more testosterone than women do and so are more likely than women to think about sex.[71]

Drive-reduction theory

Drive theory grows out of the concept that people have certain biological drives, such as hunger and thirst. As time passes the strength of the drive increases if it is not satisfied (in this case by eating). Upon satisfying a drive the drive's strength is reduced. Created by Clark Hull and further developed by Kenneth Spence, the theory became well known in the 1940s and 1950s. Many of the motivational theories that arose during the 1950s and 1960s were either based on Hull's original theory or were focused on providing alternatives to the drive-reduction theory, including Abraham Maslow's hierarchy of needs, which emerged as an alternative to Hull's approach.[72]

Drive theory has some intuitive validity. For instance when preparing food, the drive model appears to be compatible with sensations of rising hunger as the food is prepared, and, after the food has been consumed, a decrease in subjective hunger.[73] There are several problems, however, that leave the validity of drive reduction open for debate.

Cognitive dissonance theory

Suggested by Leon Festinger, cognitive dissonance occurs when an individual experiences some degree of discomfort resulting from an inconsistency between two cognitions: their views on the world around them, and their own personal feelings and actions. For example, a consumer may seek to reassure themselves regarding a purchase, feeling that another decision may have been preferable. Their feeling that another purchase would have been preferable is inconsistent with their action of purchasing the item. The difference between their feelings and beliefs causes dissonance, so they seek to reassure themselves.

While not a theory of motivation, per se, the theory of cognitive dissonance proposes that people have a motivational drive to reduce dissonance. The cognitive miser perspective makes people want to justify things in a simple way in order to reduce the effort they put into cognition. They do this by changing their attitudes, beliefs, or actions, rather than facing the inconsistencies, because dissonance is a mental strain. Dissonance is also reduced by justifying, blaming, and denying. It is one of the most influential and extensively studied theories in social psychology.

Temporal motivation theory

A recent approach in developing a broad, integrative theory of motivation is temporal motivation theory.[74] Introduced in a 2006 Academy of Management Review article,[75] it synthesizes into a single formulation the primary aspects of several other major motivational theories, including Incentive Theory, Drive Theory, Need Theory, Self-Efficacy and Goal Setting. It simplifies the field of motivation and allows findings from one theory to be translated into terms of another. Another journal article that helped to develop the Temporal Motivation Theory, "The Nature of Procrastination,[76] " received American Psychological Association's George A. Miller award for outstanding contribution to general science.

where Motivation is the desire for a particular outcome, Expectancy or self-efficacy is the probability of success, Value is the reward associated with the outcome, Impulsiveness is the individual's sensitivity to delay and Delay is the time to realization.[76]

Achievement motivation

Achievement motivation is an integrative perspective based on the premise that performance motivation results from the way broad components of personality are directed towards performance. As a result, it includes a range of dimensions that are relevant to success at work but which are not conventionally regarded as being part of performance motivation. The emphasis on performance seeks to integrate formerly separate approaches as need for achievement[77] with, for example, social motives like dominance. Personality is intimately tied to performance and achievement motivation, including such characteristics as tolerance for risk, fear of failure, and others.[78][79]

Achievement motivation can be measured by The Achievement Motivation Inventory, which is based on this theory and assesses three factors (in 17 separated scales) relevant to vocational and professional success. This motivation has repeatedly been linked with adaptive motivational patterns, including working hard, a willingness to pick learning tasks with much difficulty, and attributing success to effort.[80]

Achievement motivation was studied intensively by David C. McClelland, John W. Atkinson and their colleagues since the early 1950s.[81] This type of motivation is a drive that is developed from an emotional state. One may feel the drive to achieve by striving for success and avoiding failure. In achievement motivation, one would hope that they excel in what they do and not think much about the failures or the negatives.[82] Their research showed that business managers who were successful demonstrated a high need to achieve no matter the culture. There are three major characteristics of people who have a great need to achieve according to McClelland's research.

- They would prefer a work environment in which they are able to assume responsibility for solving problems.

- They would take calculated risk and establish moderate, attainable goals.

- They want to hear continuous recognition, as well as feedback, in order for them to know how well they are doing.[83]

Cognitive theories

Cognitive theories define motivation in terms of how people think about situations. Cognitive theories of motivation include goal-setting theory and expectancy theory.

Goal-setting theory

Goal-setting theory is based on the idea that individuals have a drive to reach a clearly defined end state. Often, this end state is a reward in itself. A goal's efficiency is affected by three features: proximity, difficulty and specificity. One common goal setting methodology incorporates the SMART criteria, in which goals are: specific, measurable, attainable/achievable, relevant, and time-bound. Time management is an important aspect, when regarding time as a contributing factor to goal achievement. Having too much time allows for distraction and procrastination, which also serves as a distraction to the subject by steering their attention away from the original goal. An ideal goal should present a situation where the time between the beginning of effort and the end state is close.[84] With an overly restricting time restraint, the subject could potentially feel overwhelmed, which could deter the subject from achieving the goal because the amount of time provided is not sufficient or rational.[85] This explains why some children are more motivated to learn how to ride a bike than to master algebra. A goal should be moderate, not too hard or too easy to complete.[85]

Most people are not optimally motivated, as many want a challenge (which assumes some kind of insecurity of success). At the same time people want to feel that there is a substantial probability that they will succeed. The goal should be objectively defined and understandable for the individual.[84] Similarly to Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs, a larger end goal is easier to achieve if the subject has smaller, more attainable yet still challenging goals to achieve first in order to advance over a period of time.[85] A classic example of a poorly specified goal is trying to motivate oneself to run a marathon when s/he has not had proper training. A smaller, more attainable goal is to first motivate oneself to take the stairs instead of an elevator or to replace a stagnant activity, like watching television, with a mobile one, like spending time walking and eventually working up to a jog.[note 1]

Expectancy theory

Expectancy theory was proposed by Victor H. Vroom in 1964. Expectancy theory explains the behavior process in which an individual selects a behavior option over another, and why/how this decision is made in relation to their goal.

There's also an equation for this theory which goes as follows:

- or

- [86]

- M (Motivation) is the amount an individual will be motivated by the condition or environment they placed themselves in. Which is based from the following hence the equation.

- E (Expectancy) is the person's perception that effort will result in performance. In other words, it's the person assessment of how well and what kind of effort will relate in better performance.

- I (Instrumentality) is the person's perception that performance will be rewarded or punished.

- V (Valence) is the perceived amount of the reward or punishment that will result from the performance."[86]

Procrastination

Procrastination is the act to voluntarily postpone or delay an intended course of action despite anticipating that you will be worse off because of that delay.[53] While procrastination was once seen as a harmless habit, recent studies indicate otherwise. In a 1997 study conducted by Dianne Tice and William James Fellow Roy Baumeister at Case Western University, college students were given ratings on an established scale of procrastination, and tracked their academic performance, stress, and health throughout the semester. While procrastinators experienced some initial benefit in the form of lower stress levels (presumably by putting off their work at first), they ultimately earned lower grades and reported higher levels of stress and illness.[87]

Procrastination can be seen as a defense mechanism.[88] Because it is less demanding to simply avoid a task instead of dealing with the possibility of failure, procrastinators choose the short-term gratification of delaying a task over the long-term uncertainty of undertaking it. Procrastination can also be a justification for when the user ultimately has no choice but to undertake a task and performs below their standard. For example, a term paper could be seem as a daunting task. If the user puts it off until the night before, they can justify their poor score by telling themselves that they would have done better with more time. This kind of justification is extremely harmful and only helps to perpetuate the cycle of procrastination.[89]

Over the years, scientists have determined that not all procrastination is the same. The first type are chronic procrastinators whom exhibit a combination of qualities from the other, more specialized types of procrastinators. "Arousal" types are usually self-proclaimed "pressure performers" and relish the exhilaration of completing tasks close to the deadline. "Avoider" types procrastinate to avoid the outcome of whatever task they are pushing back - whether it be a potential failure or success. "Avoider" types are usually very self-conscious and care deeply about other people's opinions. Lastly, "Decisional" procrastinators avoid making decisions in order to protect themselves from the responsibility that follows the outcome of events.[90]

Models of behavior change

Social-cognitive models of behavior change include the constructs of motivation and volition. Motivation is seen as a process that leads to the forming of behavioral intentions. Volition is seen as a process that leads from intention to actual behavior. In other words, motivation and volition refer to goal setting and goal pursuit, respectively. Both processes require self-regulatory efforts. Several self-regulatory constructs are needed to operate in orchestration to attain goals. An example of such a motivational and volitional construct is perceived self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is supposed to facilitate the forming of behavioral intentions, the development of action plans, and the initiation of action. It can support the translation of intentions into action.

John W. Atkinson, David Birch and their colleagues developed the theory of "Dynamics of Action" to mathematically model change in behavior as a consequence of the interaction of motivation and associated tendencies toward specific actions.[91][92] The theory posits that change in behavior occurs when the tendency for a new, unexpressed behavior becomes dominant over the tendency currently motivating action. In the theory, the strength of tendencies rises and falls as a consequence of internal and external stimuli (sources of instigation), inhibitory factors, and consummatory in factors such as performing an action. In this theory, there are three causes responsible for behavior and change in behavior:

Thematic apperception test

Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) was developed by American psychologists Henry A. Murray and Christina D. Morgan at Harvard during the early 1930s. Their underlying goal was to test and discover the dynamics of personality such as internal conflict, dominant drives, and motives. Testing is derived of asking the individual to tell a story, given 31 pictures that they must choose ten to describe. To complete the assessment, each story created by the test subject must be carefully recorded and monitored to uncover underlying needs and patterns of reactions each subject perceives. After evaluation, two common methods of research, Defense Mechanisms Manual (DMM) and Social Cognition and Object Relations (SCOR), are used to score each test subject on different dimensions of object and relational identification. From this, the underlying dynamics of each specific personality and specific motives and drives can be determined.

Attribution theory

Attribution theory describes individual's motivation to formulate explanatory attributions ("reasons") for events they experience, and how these beliefs affect their emotions and motivations.[95] Attributions are predicted to alter behavior, for instance attributing failure on a test to a lack of study might generate emotions of shame and motivate harder study. Important researchers include Fritz Heider and Bernard Weiner. Weiner's theory differentiates intrapersonal and interpersonal perspectives. Intrapersonal includes self-directed thoughts and emotions that are attributed to the self. The interpersonal perspective includes beliefs about the responsibility of others and emotions directed at other people, for instance attributing blame to another individual.[96]

Approach versus avoidance

Approach motivation (i.e., incentive salience) can be defined as when a certain behavior or reaction to a situation/environment is rewarded or results in a positive or desirable outcome. In contrast, avoidance motivation (i.e., aversive salience) can be defined as when a certain behavior or reaction to a situation/environment is punished or results in a negative or undesirable outcome.[97][98] Research suggests that, all else being equal, avoidance motivations tend to be more powerful than approach motivations. Because people expect losses to have more powerful emotional consequences than equal-size gains, they will take more risks to avoid a loss than to achieve a gain.[97]

Conditioned taste aversion.

“A strong dislike (nausea reaction) for food because of prior Association with of that food with nausea or upset stomach.”[13]

Conditioned taste aversion is the only type of conditioning that only needs one exposure. It does not need to be the specific food or drinks that cause the taste. Conditioned taste aversion can also be attributed to extenuating circumstances. An example of this can be eating a rotten apple. Eating the apple then immediately throwing up. Now it is hard to even near an apple without feeling sick. Conditioned taste aversion can also come about by the mere associations of two stimuli. Eating a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, but also have the flu. Eating the sandwich makes one feel nauseous, so one throws up, now one cannot smell peanut butter without feeling queasy. Though eating the sandwich does not cause one to through up, they are still linked.[13]

Unconscious Motivation

In his book A General Introduction to Psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud explained his theory on the conscious-unconscious distinction.[99] To explain this relationship, he used a two-room metaphor. The smaller of the two rooms is filled with a person's preconscious, which is the thoughts, emotions, and memories that are available to a person's consciousness. This room also houses a person's consciousness, which is the part of the preconscious that is the focus at that given time. Connected to the small room is a much larger room that houses a person's unconscious. This part of the mind is unavailable to a person's consciousness and consists of impulses and repressed thoughts. The door between these two rooms acts as the person's mental censor. Its job is to keep anxiety inducing thoughts and socially unacceptable behaviors or desires out of the preconscious. Freud describes the event of a thought or impulse being denied at the door as repression, one of the many defense mechanisms. This process is supposed to protect the individual from any embarrassment that could come from acting on these impulses or thoughts that exist in the unconscious.

In terms of motivation, Freud argues that unconscious instinctual impulses can still have great influence on behavior even though the person is not aware of the source.[100] When these instincts serve as a motive, the person is only aware of the goal of the motive, and not its actual source. He divides these instincts into sexual instincts, death instincts, and ego or self-preservation instincts. Sexual instincts are those that motivate humans to stay alive and ensure the continuation of the mankind. On the other hand, Freud also maintains that humans have an inherent drive for self-destruction, or the death instinct. Similar to the devil and angel that everyone has on there should, the sexual instinct and death instinct are constantly battling each other to both be satisfied. The death instinct can be closely related to Freud's other concept, the id, which is our need to experience pleasure immediately, regardless of the consequences. The last type of instinct that contributes to motivation is the ego or self-preservation instinct. This instinct is geared towards assuring that a person feels validated in whatever behavior or thought they have. The mental censor, or door between the unconscious and preconscious, helps satisfy this instinct. For example, one may be sexually attracted to a person, due to their sexual instinct, but the self-preservation instinct prevents them to act on this urge until that person finds that it is socially acceptable to do so. Quite similarly to his psychic theory that deals with the id, ego, and superego, Freud's theory of instincts highlights the interdependence of these three instincts. All three instincts serve as a checks and balances system to control what instincts are acted on and what behaviors are used to satisfy as many of them at once.

Priming

Priming is a phenomenon, often used as an experimental technique, whereby a specific stimulus sensitizes the subject to later presentation of a similar stimulus.[101]

“Priming refers to an increased sensitivity to certain stimuli, resulting from prior exposure to related visual or audio messages. When an individual is exposed to the word “cancer,” for example, and then offered the choice to smoke a cigarette, we expect that there is a greater probability that they will choose not to smoke as a result of the earlier exposure.”[102]

Priming can affect motivation, in the way that we can be motived to do things by an outside source.

Priming can be linked with the mere exposer theory. People tend to like things that they have been exposed to before. Mere exposer theory is used by advertising companies to get people to buy their products. An example of this is seeing a picture of the product on a sign and then buying that product later. If an individual is in a room with two strangers they are more likely to gravitate towards the person that they occasionally pass on the street, than the person that they have never seen before. An example of the use of mere exposure theory can be seen in product placements in movies and TV shows. We see a product that our is in our favorite movie, and we are more inclined to buy that product when we see it again.[103]

Priming can fit into these categories; Semantic Priming, Visual Priming, Response Priming, Perceptual and Conceptual Priming, Positive and Negative Priming, Associative and Context Priming, and Olfactory Priming. Visual and Semantic priming is the most used in motivation. Most priming is linked with emotion, the stronger the emotion, the stronger the connection between memory and the stimuli.[102]

Priming also has an effect on drug users. In this case, it can be defined at, the reinstatement or increase in drug craving by a small dose of the drug or by stimuli associated with the drug. If a former drug user is in a place where they formerly did drugs, then they are tempted to do that same thing again even if they have been clean for years.[13]

Conscious Motivation

Freud relied heavily upon the theories of unconscious motivation as explained above, but Allport (a researcher in 1967) looked heavily into the powers of conscious motivation and the effect it can have upon goals set for an individual. This is not to say that unconscious motivation should be ignored with this theory, but instead it focuses on the thought that if we are aware of our surroundings and our goals, we can then actively and consciously take steps towards them.[104]

He also believed that there are three hierarchical tiers of personality traits that affect this motivation:[104]

- Cardinal traits: Rare, but strongly determines a set behavior and can't be changed

- Central traits: Present around certain people, but can be hidden

- Secondary traits: Present in all people, but strongly reliant on context- can be altered as needed and would be the focus of a conscious motivation effort.

Mental Fatigue

Mental fatigue is being tired, exhausted, or not functioning effectively. Not wanting to proceed further with the current mental course of action, this in contrast with physical fatigue, because in most cases no physical activity is done.[105] This is best seen in the workplace or schools. A perfect example of mental fatigue is seen in college students just before finals approach. One will notice that students start eating more than they usually do and care less about interactions with friends and classmates. Mental fatigue arises when an individual becomes involved in a complex task but does no physical activity and is still worn out, the reason for this is because the brain uses about 20 percent of the human body's metabolic heart rate. The brain consumes about 10.8 calories every hour. Meaning that a typical human adult brain runs on about twelve watts of electricity or a fifth of the power need to power a standard light bulb.[106] These numbers represent an individual's brain working on routine tasks, things that are not challenging. One study suggests that after engaging in a complex task, an individual tends to consume about two hundred more calories than if they had been resting or relaxing; however, this appeared to be due to stress, not higher caloric expenditure. [106] The symptoms of mental fatigue can range from low motivation and loss of concentration to the more severe symptoms of headaches, dizziness, and impaired decision making and judgment. Mental fatigue can affect an individual's life by causing a lack of motivation, avoidance of friends and family members and changes in one's mood. To treat mental fatigue, one must figure out what is causing the fatigue. Once the cause of the stress has been identified the individual must determine what they can do about it. Most of the time mental fatigue can be fixed by a simple life change like being more organized or learning to say no.[107] According to the study: Mental fatigue caused by prolonged cognitive load associated with sympathetic hyperactivity, “there is evidence that decreased parasympathetic activity and increased relative sympathetic activity are associated with mental fatigue induced by prolonged cognitive load in healthy adults.[108]” this means that though no physical activity was done, the sympathetic nervous system was triggered. An individual who is experiencing mental fatigue will not feel relaxed but feel the physical symptoms of stress.

Learned Industriousness

Learned industriousness theory is the theory about an acquired ability to sustain the physical or mental effort. It can also be described as being persistent despite the building up subjective fatigue.[105] This is the ability to push through to the end for a greater or bigger reward. The more significant or more rewarding the incentive, the more the individual is willing to do to get to the end of a task.[109] This is one of the reasons that college students will go on to graduate school. The students may be worn out, but they are willing to go through more school for the reward of getting a higher paying job when they are out of school.

Practical applications

The control of motivation is only understood to a limited extent. There are many different approaches of motivation training, but many of these are considered pseudoscientific by critics. To understand how to control motivation it is first necessary to understand why many people lack motivation.

Like any theory, motivational theory makes predictions about what will work in practice. For instance McGregor's Theory Y makes the assumption that the average person not only accepts, but also seeks out responsibility, enjoys doing work and, therefore, is more satisfied when they have a wider range of work to do.[32] The practical implication is that, as a firm gives individuals’ greater responsibilities, they will feel a greater sense of satisfaction and, subsequently, more commitment to the organization. Likewise allocating more work is predicted to increase engagement. Additionally, Malone argues that the delegation of responsibility encourages motivation because employees have creative control over their work and increases productivity as many people can work collaboratively to solve a problem rather than just one manager tackling it alone.[110] Others have argued that participation in decision making boosts morale and commitment to the organization, subsequently increasing productivity.[111][112] Likewise, if teams and membership increase motivation (as reported in the classic Hawthorn Western Electric Company studies[33]) incorporating teams make provide incentives to work. In general, motivation theory is often applied to employee motivation.[113]

Applications in Business

Within Maslow's hierarchy of needs (first proposed in 1943), at lower levels (such as physiological needs) money functions as a motivator; however, it tends to have a motivating effect on staff that lasts only for a short period (in accordance with Herzberg's two-factor model of motivation of 1959). At higher levels of the hierarchy, praise, respect, recognition, empowerment and a sense of belonging are far more powerful motivators than money, as both Abraham Maslow's theory of motivation and Douglas McGregor's theory X and theory Y (originating in the 1950s and pertaining to the theory of leadership) suggest.