Geography of Ireland

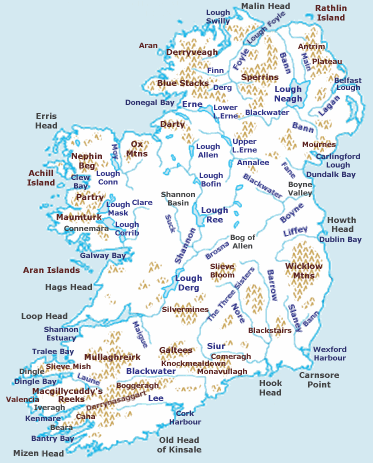

Ireland is an island in Northwestern Europe in the north Atlantic Ocean. The island lies on the European continental shelf, part of the Eurasian Plate. The island's main geographical features include low central plains surrounded by coastal mountains. The highest peak is Carrauntoohil (Irish: Corrán Tuathail), which is 1,041 meters (3,415 ft) above sea level. The western coastline is rugged, with many islands, peninsulas, headlands and bays. The island is bisected by the River Shannon, which at 360.5 km (224 mi) with a 102.1 km (63 mi) estuary is the longest river in Ireland and flows south from County Cavan in Ulster to meet the Atlantic just south of Limerick. There are a number of sizeable lakes along Ireland's rivers, of which Lough Neagh is the largest.

.jpg) | |

| Continent | Europe |

|---|---|

| Region | Western/Northern Europe |

| Coordinates | 53°20.65′N 6°16.05′W |

| Area | Ranked 118th |

| • Total | 70,273 km2 (27,133 sq mi) |

| • Land | 98.2% |

| • Water | 1.8% |

| Coastline | 1,448 km (900 mi) |

| Highest point | Carrauntoohil 1,041 meters (3,415 ft) |

| Lowest point | North Slob −3 meters (−10 ft) |

| Longest river | River Shannon 360.5 km (224.0 mi) |

| Largest lake | Lough Neagh 392 km2 (151 sq mi) |

| Climate | temperate oceanic climate with abundant rainfall |

| Terrain | flat, low-lying area in the midlands, ringed by mountain ranges |

| Natural Resources | mineral deposits, natural gas, marine resources |

| Natural Hazards | Cyclones, thunderstorms |

| Environmental Issues | Acidic soil, bogs, debris |

Politically, the island consists of the Republic of Ireland, with jurisdiction over about five-sixths of the island; and Northern Ireland, a constituent country (and an unconfirmed "practical" exclave) of the United Kingdom, with jurisdiction over the remaining sixth. Located west of the island of Great Britain, it is located at approximately 53°N 8°W. It has a total area of 84,421 km2 (32,595 sq mi).[1] It is separated from Great Britain by the Irish Sea and from mainland Europe by the Celtic Sea. Ireland and Great Britain, together with nearby islands, are known collectively as the British Isles; as the term British Isles is controversial in relation to Ireland, the alternative term 'Britain and Ireland' is increasingly preferred.[2]

Geological development

The geology of Ireland is diverse. Different regions contain rocks belonging to different geological periods, dating back almost 2 billion years. The oldest known Irish rock is about 1.7 billion years old and is found on Inishtrahull Island off the north coast of Inishowen[3][4] and on the mainland at Annagh Head on the Mullet Peninsula.[5] The newer formations are the drumlins and glacial valleys as a result of the last ice age, and the sinkholes and cave formations in the limestone regions of Clare.[6][7]

Ireland's geological history covers everything from volcanism and tropical seas to the last glacial period. Ireland was formed in two distinct parts and slowly joined together, uniting about 440 million years ago. As a result of tectonics and the effect of ice, the sea level has risen and fallen. In every area of the country the rocks which formed can be seen as a result. Finally, the impact of the glaciers shaped the landscape seen today.[8] The variation between the two areas, along with the differences between volcanic areas and shallow seas, led to a range of soils. There are extensive bogs and free-draining brown earths. The mountains are granite, sandstone, limestone with karst areas, and basalt formations.[9][10][11][12]

Most of Ireland was likely above sea level during the last 60 million years. As such its landscapes have been shaped by erosion and weathering on land.[13] Protracted erosion does also means most of the Paleogene and Neogene sediments have been eroded away or, as known in a few cases, buried by Quaternary deposits.[14] Before the Quaternary glaciations affected Ireland the landscape had developed thick weathered regolith on the uplands and karst in the lowlands.[13] There has been some controversy regarding the origin of the planation surfaces found in Ireland.[14][15] While some have argued for an origin in marine planation others regard these surfaces as peneplains formed by weathering and fluvial erosion. Not only is their origin disputed but also their actual extent and the relative role of sea-level change and tectonics in their shaping.[14] Most river systems in Ireland formed in the Cenozoic before the Quaternary glaciations. Rivers follow for most of their course structural features of the geology of Ireland.[13] Marine erosion since the Miocene may have made Ireland's western coast retreat more than 100 km. Pre-Quaternary relief was more dramatic than today's glacier-smoothened landscapes.[13]

Physical geography

Mountain ranges

Ireland consists of a mostly flat low-lying area in the midlands, ringed by mountain ranges such as (beginning in County Kerry and working counter-clockwise) the MacGillycuddy's Reeks, Comeragh Mountains, Blackstairs Mountains, Wicklow Mountains, the Mournes, Glens of Antrim, Sperrin Mountains, Bluestack Mountains, Derryveagh Mountains, Ox Mountains, Nephinbeg Mountains and the Twelve Bens/Maumturks group. Some mountain ranges are further inland in the south of Ireland, such as the Galtee Mountains (the highest inland range),[16] Silvermine and Slieve Bloom Mountains. The highest peak Carrauntoohil, 1,038 m (3,405 ft) high,[17] is in the MacGillycuddy's Reeks, a range of glacier-carved sandstone mountains. Ireland's mountains are not high – only three peaks are over 1,000 m (3,281 ft)[17] and another 457 exceed 500 m (1,640 ft).[18] Ireland is sometimes known as the "Emerald Isle" because of its green landscape.

Forests

Ireland, like the neighbouring Great Britain, was once covered in forest. Clearing of forests began in the Neolithic Age, resulting in forest cover of only 1% by the start of the twentieth century.[19] As of 2019, total tree cover in the Republic of Ireland stood at 10.5% of land area.[20] The figure for native forest stood at 1% in 2018; the second lowest in Europe behind Iceland.[21]

Rivers and lakes

The main river in Ireland is the River Shannon. 360.5 km (224.0 mi) The longest river in Ireland, it separates the midlands of Ireland from the west of the island. The river develops into three lakes along its course, Lough Allen, Lough Ree, and Lough Derg. Of these, Lough Derg is the largest.[17] The River Shannon enters the Atlantic Ocean in Limerick city in the Shannon Estuary. Other major rivers include the River Liffey, River Lee, River Blackwater, River Nore, River Suir, River Barrow, River Bann, River Foyle, River Erne, and River Boyne (see the list of rivers in Ireland).

Lough Neagh, in Ulster,[17] is the largest lake in Ireland and Britain with an area of 392 km2 (151 sq mi). The largest lake in the Republic of Ireland is Lough Corrib 176 km2 (68 sq mi). Other large lakes include Lough Erne.[17]

Inlets

In County Donegal, Lough Swilly separates the western side of the Inishowen peninsula. Lough Foyle on the other side, is one of Ireland's larger inlets, situated between County Donegal and County Londonderry.[22] Clockwise round the coast is Belfast Lough, between County Antrim and County Down.[23] Also in County Down is Strangford Lough, actually an inlet partially separating the Ards peninsula from the mainland. Further south, Carlingford Lough is situated between Down and County Louth.[23]

Dublin Bay is the next sizeable inlet. The east coast of Ireland has no major inlets until Wexford Harbour at the mouth of the River Slaney.[24] On the south coast, Waterford Harbour is situated at the mouth of the River Suir[25] (into which the other two of the Three Sisters (River Nore and River Barrow) flow). The next major inlet is Cork Harbour, at the mouth of the River Lee, in which Great Island is situated.

Dunmanus Bay, Kenmare estuary and Dingle Bay are all inlets between the peninsulas of County Kerry. North of these is the Shannon Estuary. Between north County Clare and County Galway is Galway Bay. Clew Bay is located on the coast of County Mayo, south of Achill Island, while Broadhaven Bay, Blacksod Bay and Sruth Fada Conn bays are situated in northwest Connacht, in North Mayo. Killala Bay is on the northeast coast of Mayo. Donegal Bay is a major inlet between County Donegal and County Sligo.[22]

Headlands

Malin Head is the most northerly point in Ireland,[26] while Mizen Head is one of the most southern points, hence the term "from Malin to Mizen" (or the reverse) is used for anything applying to the island of Ireland as a whole. Carnsore Point is another extreme point of Ireland, being the southeastern most point of Ireland. Hook Head and the Old Head of Kinsale are two of many headlands along the south coast.

Loop Head is the headland at which County Clare comes to a point on the west coast of Ireland, with the Atlantic on the north, and the Shannon estuary to the south. Hag's Head is another headland further up Clare's north/western coastline, with the Cliffs of Moher along the coastline north of the point.

Erris Head is the northwesternmost point of Connacht.

Islands and peninsulas

Apart from Ireland itself, Achill Island to its northwest is now considered the largest island in the group. The island is inhabited, and is connected to the mainland by a bridge.[27] Some of the next largest islands are the Aran Islands, off the coast of southern Connacht, host to an Irish-speaking community, or Gaeltacht. Valentia Island off the Iveragh peninsula is also one of Ireland's larger islands, and is relatively settled, as well as being connected by a bridge at its southeastern end. Omey Island, off the coast of Connemara is a tidal island.

Some of the best-known peninsulas in Ireland are in County Kerry; the Dingle peninsula, the Iveragh peninsula and the Beara peninsula. The Ards peninsula is one of the larger peninsulas outside Kerry. The Inishowen peninsula in County Donegal includes Ireland's most northerly point, Malin Head and several important towns including Buncrana on Lough Swilly, Carndonagh and Moville on Lough Foyle. Ireland's most northerly land feature is Inishtrahull island, off Malin Head. Rockall Island may deserve this honour but its status is disputed, being claimed by the United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland, Denmark (for the Faroe Islands) and Iceland. The most southerly point is the Fastnet Rock.

The Hebrides off Scotland and Anglesey off Wales were grouped with Ireland ("Hibernia") by the Greco-Roman geographer Ptolemy,[28] but this is no longer common.

Climate

The climate of Ireland is mild, moist and changeable with abundant rainfall and a lack of temperature extremes. Ireland's climate is defined as a temperate oceanic climate, or Cfb on the Köppen climate classification system, a classification it shares with most of northwest Europe.[29][30] The country receives generally warm summers and mild winters. It is considerably warmer than other areas at the same latitude on the other side of the Atlantic, such as in Newfoundland, because it lies downwind of the Atlantic Ocean. It is also warmer than maritime climates near the same latitude, such as the Pacific Northwest as a result of heat released by the Atlantic overturning circulation that includes the North Atlantic Current and Gulf Stream. For comparison, Dublin is 9 °C warmer than St. John's in Newfoundland in winter and 4 °C warmer than Seattle in the Pacific Northwest in winter.[31]

The influence of the North Atlantic Current also ensures the coastline of Ireland remains ice-free throughout the winter.[32] The climate in Ireland does not experience extreme weather, with tornadoes and similar weather features being rare.[33][34] However, Ireland is prone to eastward moving cyclones which come in from the North Atlantic.[35]

The prevailing wind comes from the southwest, breaking on the high mountains of the west coast.[30] Rainfall is therefore a particularly prominent part of western Irish life, with Valentia Island, off the west coast of County Kerry, getting almost twice as much annual rainfall as Dublin on the east (1,400 mm or 55.1 in vs. 762 mm or 30.0 in).[36]

January and February are the coldest months of the year, and mean daily air temperatures fall between 4 and 7 °C (39.2 and 44.6 °F) during these months. July and August are the warmest, with mean daily temperatures of 14 to 16 °C (57.2 to 60.8 °F), whilst mean daily maximums in July and August vary from 17 to 18 °C (62.6 to 64.4 °F) near the coast, to 19 to 20 °C (66.2 to 68.0 °F) inland. The sunniest months are May and June, with an average of five to seven hours sunshine per day.[37]

Though extreme weather events in Ireland are comparatively rare when compared with other countries in the European Continent, they do occur. Atlantic depressions, occurring mainly in the months of December, January and February, can occasionally bring winds of up to 160 km/h or 99 mph to Western coastal counties; while the summer months, and particularly around late July/early August, thunderstorms can develop.[38][39][40]

The table shows mean climate figures for the Dublin Airport weather station over a thirty-year period. Climate statistics based on the counties of Northern Ireland vary slightly but are not significantly different.[41]

| Climate data for Dublin Airport | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 16.6 (61.9) |

15.3 (59.5) |

21.3 (70.3) |

20.5 (68.9) |

23.4 (74.1) |

25.1 (77.2) |

27.6 (81.7) |

28.7 (83.7) |

23.9 (75.0) |

21.2 (70.2) |

18.0 (64.4) |

16.2 (61.2) |

28.7 (83.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7.6 (45.7) |

7.5 (45.5) |

9.5 (49.1) |

11.4 (52.5) |

14.2 (57.6) |

17.2 (63.0) |

18.9 (66.0) |

18.6 (65.5) |

16.6 (61.9) |

13.7 (56.7) |

9.8 (49.6) |

8.4 (47.1) |

12.8 (55.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.5 (36.5) |

2.5 (36.5) |

3.1 (37.6) |

4.4 (39.9) |

6.8 (44.2) |

9.6 (49.3) |

11.4 (52.5) |

11.1 (52.0) |

9.6 (49.3) |

7.6 (45.7) |

4.2 (39.6) |

3.4 (38.1) |

6.0 (42.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −9.4 (15.1) |

−6.2 (20.8) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

−3.7 (25.3) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

1.5 (34.7) |

4.8 (40.6) |

4.1 (39.4) |

1.7 (35.1) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

−10.1 (13.8) |

−10.1 (13.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 69.4 (2.73) |

50.4 (1.98) |

53.8 (2.12) |

50.7 (2.00) |

55.1 (2.17) |

56.0 (2.20) |

49.9 (1.96) |

70.5 (2.78) |

66.7 (2.63) |

69.7 (2.74) |

64.7 (2.55) |

75.6 (2.98) |

732.7 (28.85) |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 1.8 | 2.5 | 3.6 | 5.2 | 6.1 | 6.0 | 5.4 | 5.1 | 4.3 | 3.1 | 2.4 | 1.7 | 3.9 |

| Source: [42] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Belfast | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 13 (55) |

14 (57) |

19 (66) |

21 (70) |

26 (79) |

28 (82) |

29 (84) |

28 (82) |

26 (79) |

21 (70) |

16 (61) |

14 (57) |

29 (84) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 6 (43) |

7 (45) |

9 (48) |

12 (54) |

15 (59) |

18 (64) |

18 (64) |

18 (64) |

16 (61) |

13 (55) |

9 (48) |

7 (45) |

12 (54) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2 (36) |

2 (36) |

3 (37) |

4 (39) |

6 (43) |

9 (48) |

11 (52) |

11 (52) |

9 (48) |

7 (45) |

4 (39) |

3 (37) |

6 (43) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −13 (9) |

−12 (10) |

−12 (10) |

−4 (25) |

−3 (27) |

−1 (30) |

4 (39) |

1 (34) |

−2 (28) |

−4 (25) |

−6 (21) |

−11 (12) |

−13 (9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 80 (3.1) |

52 (2.0) |

50 (2.0) |

48 (1.9) |

52 (2.0) |

68 (2.7) |

94 (3.7) |

77 (3.0) |

80 (3.1) |

83 (3.3) |

72 (2.8) |

90 (3.5) |

846 (33.3) |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3.4 |

| Source: [43] | |||||||||||||

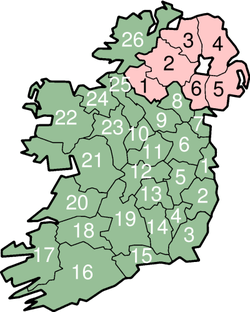

Political and human geography

Ireland is divided into four provinces, Connacht, Leinster, Munster and Ulster, and 32 counties.[44] Six of the nine Ulster counties form Northern Ireland and the other 26 form the state, Ireland. The map shows the county boundaries for all 32 counties.

|

(Republic of) Ireland |

Northern Ireland |

From an administrative viewpoint, 21 of the counties in the Republic are units of local government. The other six have more than one local council area, resulting in a total of 31 county-level authorities. County Tipperary had two ridings, North Tipperary and South Tipperary, originally established in 1838, renamed in 2001[45] and amalgamated in 2014.[46] The cities of Dublin, Cork and Galway have city councils and are administered separately from the counties bearing those names. The cities of Limerick and Waterford were merged with their respective county councils in 2014 to form new city and county councils. The remaining part of County Dublin is divided into Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown, Fingal, and South Dublin.[44]

Electoral areas in Ireland (the state) are called constituencies in accordance with Irish law, mostly follow county boundaries. Maintaining links to the county system is a mandatory consideration in the re-organisation of constituency boundaries by a Constituency Commission.[47]

In Northern Ireland, a major re-organisation of local government in 1973 replaced the six traditional counties and two county boroughs (Belfast and Derry) by 26 single-tier districts,[48] which, apart from Fermanagh cross the traditional county boundaries. The six counties and two county-boroughs remain in use for purposes such as Lieutenancy. In November 2005, proposals were announced which would see the number of local authorities reduced to seven.[49] The island's total population of nearly 7 million people is concentrated on the east coast, particularly in Dublin and Belfast and their surrounding areas.[50][51]

Natural resources

| Life in Ireland |

|---|

| Culture |

| Economy |

| General |

|

| Society |

| Politics |

|

| Policies |

Bogs

Ireland has 12,000 km² (about 4,600 sq miles) of bogland,[52] consisting of two distinct types: blanket bogs and raised bogs. Blanket bogs are the more widespread of the two types. They are essentially a product of human activity aided by the moist Irish climate. Blanket bogs formed on sites where Neolithic farmers cleared trees for farming. As the land so cleared fell into disuse, the soil began to leach and become more acidic, producing a suitable environment for the growth of heather and rushes. The debris from these plants accumulated and a layer of peat formed. One of the largest expanses of Atlantic blanket bog in Ireland is to be found in County Mayo.[53]

Raised bogs are most common in the Shannon basin. They formed when depressions left behind after the last ice age filled with water to form lakes. Debris from reeds in these lakes formed a layer at the bottom of the water to form fens. Dead plant matter, preserved by the water, eventually filled the lake, covering this alkaline base. This led to the growth of plants that could survive in a wet low-nutrient acidic medium, The plants kept growing and dying, increasingly well preserved by the acidic conditions and they piled up raising the surface of the bog above the surrounding land, forming raised bogs.[54]

Since the 17th century, peat has been cut for fuel for domestic heating and cooking, and it is called turf when so used. The process accelerated as commercial exploitation of bogs grew. In the 1940s, machines for cutting turf were introduced and larger-scale harvesting became possible. In the Republic, this became the responsibility of a semi-state company called Bord na Móna. In addition to domestic uses, commercially extracted turf is used in a number of industries, producing peat briquettes for domestic fuel and milled peat for electricity generation.[55] More recently peat is being combined with biomass for dual-firing electricity generation.[56]

In recent years, the destruction of bogs has raised environmental concerns. The issue is particularly acute for raised bogs which were more widely mined as they yield a higher-grade fuel than blanket bogs. Plans are now in place in both the Republic and Northern Ireland to conserve most of the remaining raised bogs on the island.[57]

Marine resources

Ireland has major marine resources, with a significant fishing industry in the Atlantic Ocean. The Exclusive Economic Zone of the Republic of Ireland is 410,310 km2 (158,420 sq mi).

Oil, natural gas and minerals

Offshore exploration for natural gas began in 1970.[58] The first major discovery was the Kinsale Head gas field in 1971.[59] Next were the smaller Ballycotton gas field in 1989,[58] and the Corrib gas field in 1996.[60] Exploitation of the Corrib project has yet to get off the ground because the controversial proposal to refine the gas onshore, rather than at sea, has been met with widespread opposition. Gas from these fields is pumped ashore and used for both domestic and industrial purposes. The Helvick oil field, estimated to contain over 28 million barrels (4,500,000 m3) of oil, was discovered in 2000.[61] Ireland is the largest European producer of zinc, with three operating zinc-lead mines at Navan, Galmoy and Lisheen. Other mineral deposits with actual or potential commercial value include gold, silver, gypsum, talc, calcite, dolomite, roofing slate, limestone aggregate, building stone, sand and gravel.[62]

In May 2007 the Department of Communications, Marine and Natural Resources (now replaced by the Department of Communications, Energy and Natural Resources) reported that there may be volumes over 130 billion barrels (2.1×1010 m3) of petroleum and 50 trillion cubic feet (1,400 km3) of natural gas in Irish waters[63] – worth trillions of Euro, if true. The minimum confirmed amount of oil in the Irish Atlantic waters is 10 billion barrels (1.6×109 m3), worth over €450 billion. There are also areas of petroleum and natural gas on shore, for example the Lough Allen basin, with 9.4 trillion cubic feet (270 km3) of gas and 1.5 billion barrels (240,000,000 m3) of oil, valued at €74.4 billion. Already some fields are being exploited, such as the Spanish Point field, with 1.25 trillion cubic feet (35 km3) of gas and 206 million barrels (32,800,000 m3) of oil, valued at €19.6 billion. The Corrib Basin is also quite large, worth anything up to €87 billion, while the Dunquin gas field, initially estimated to have 25 trillion cubic feet (710 km3) of natural gas and 4.13 billion barrels (657,000,000 m3) of petroleum[63] but 2012 revised estimates suggest only 14 trillion cubic feet (400 km3) of natural gas and .5 billion barrels (79,000,000 m3) barrels of oil condensate.[64]

In March 2012 the first commercial oil well was drilled 70 km off the Cork coast by Providence Resources. The Barryroe oil well is yielding 3500 barrels per day; at current oil prices of $120 a barrel Barryroe oil well is worth in excess of €2.14bn annually.[65]

See also

- Extreme points of Ireland

- Gravity Anomalies of Britain and Ireland

- Coastal landforms of Ireland

- Geographical centre of Ireland

References

- Nolan, Professor William. "Geography of Ireland". Government of Ireland. Archived from the original on 24 November 2009. Retrieved 15 October 2009.

- Davies, Alistair; Sinfield, Alan (2000), British Culture of the Postwar: An Introduction to Literature and Society, 1945–1999, Routledge, p. 9, ISBN 978-0-415-12811-7,

Many of the Irish dislike the 'British' in 'British Isles', while the Welsh and Scottish are not keen on 'Great Britain'. ... In response to these difficulties, 'Britain and Ireland' is becoming preferred usage although there is a growing trend amounts some critics to refer to Britain and Ireland as 'the archipelago'.

- "Site Synopsis (Inishtrahull)" (PDF). National Parks and Wildlife Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 30 January 2008.

- Woodcock, N. H. (2000). Geological History of Britain and Ireland. Blackwell Publishing. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-632-03656-1.

- Daly, J. Stephen (1996). "Pre-Caledonian History of the Annagh Gneiss Complex North-Western Ireland, and Correlation with Laurentia-Baltica". Irish Journal of Earth Sciences. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy. 15: 5–18. JSTOR 30002311.

- Woodcock, N. H. (1994). Geology and Environment in Britain and Ireland. CRC Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-85728-054-8.

- Moody, Theodore William; Francis John Byrne; Francis X Martin; Art Cosgrove (2005). A New History of Ireland. Oxford University Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-19-821737-4.

- Foster, John Wilson; Helena C. G. Chesney (1998). Nature in Ireland: A Scientific and Cultural History. McGill-Queen's Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-7735-1817-9.

- "Bog of Allen". Ask About Ireland. Department of the Environment, Community and Local Government. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- "Giant's Causeway and Causeway Coast". Unesco World Heritage Sites. Retrieved 23 January 2008.

- Brittle tectonism in relation to the Palaeogene evolution of the Thulean/NE Atlantic domain: a study in Ulster (Subscription required) Retrieved on 10 November 2007

- Deegan, Gordon (27 May 1999). "Blasting threatens future of stalactite". Irish Examiner. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 23 January 2008.

- Simms, Michael J.; Coxon, Peter (2017). "The Pre-Quaternary Landscape of Ireland". In Coxon, Peter; McCarron, Stephen; Mitchell, Fraser (eds.). Advances in Irish Quaternary Studies. Atlantis Advances in Quaternary Science. Atlantis Press. p. 19–42. ISBN 978-94-6239-219-9.

- Mitchell, G.F. (1980). "The search for Tertiary Ireland". Journal of Earth Sciences Royal Dublin Society. 3: 13–33.

- Miller, A.A. (1955). "The origin of the South Ireland Peneplane". Irish Geography. 3 (2): 79–86. doi:10.1080/00750775509555491.

- "Glen of Aherlow". Glen of Aherlow Fáilte Society. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- "Ordnance Survey FAQs". Ordnance Survey of Ireland. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- "500 m Irish Mountains". MountainViews.com. Retrieved 11 January 2008.

- Sullivan, Arthur (27 July 2018). "Ireland's forests: Watching a vanished world return". Environment. Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- "Forestry Inventory finds 10.5% of Ireland's total land area is forest". TheJournal.ie. 15 October 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- "Forestry and Woodland in Ireland". Irish Wildlife Trust. February 2018. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- Joyce, P.W. (1900). "Description of County Donegal". Atlas and Cyclopedia of Ireland. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- Joyce, P.W. (1900). "Description of County Down". Atlas and Cyclopedia of Ireland. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- Joyce, P.W. (1900). "Description of County Wexford". Atlas and Cyclopedia of Ireland. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- Joyce, P.W. (1900). "Description of County Waterford". Atlas and Cyclopedia of Ireland. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- "Malin Head". Weather Observing Stations. Met Éireann. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- Walsh, David; Sean Pierce (2004). Oileain: A Guide to the Irish Islands. Pesda Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-9531956-9-5.

- Ptolemy, Geog., Bk. 2, Ch. 1 & 2.

- Peel, M. C. and Finlayson, B. L. and McMahon, T. A. (2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen–Geiger climate classification". Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 11 (5): 1633–1644. doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007. ISSN 1027-5606.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) (direct: Final Revised Paper)

- "Marine Climatology". Met Éireann. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- McCarthy, G. D., Gleeson, E. and Walsh, S. (2015) The influence of the Ocean on the Climate of Ireland. Weather. 70, 8, 242–245, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/wea.2543/abstract

- "Climate". Education in Ireland.

- "Exceptional weather events" (PDF). Met Éireann. March 1995. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 October 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- "Met Éireann Weather Warning System Explained". Met Éireann. 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- Devoy, R.J.N. (2008). Coastal vulnerability and the implications of sea-level rise for Ireland. Journal of Coastal Research, 24(2) pp. 327-331

- "Rainfall in Ireland". Climate. Met Éireann. 2017. Archived from the original on 29 September 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- "Sunshine in Ireland". Met Éireann. Retrieved 23 January 2008.

- "Evidence of winter storms". Independent Newspapers. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- "Evidence of storms". Irish Examiner. 13 February 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- "July Thunderstorm" (PDF). Met Éireann. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 April 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- "Northern Ireland climate information". UK Met Office. Retrieved 30 September 2009.

- "30 Year Averages – Dublin Airport". Met Éireann. Met Éireann. Archived from the original on 30 December 2010. Retrieved 23 January 2008.

- "Belfast, Northern Ireland – Average Conditions". BBC Weather Centre. BBC. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- "Placenames (Counties and Provinces) Order 2003" (PDF). Department of Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht. 30 October 2003. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- Callanan, Mark; Keogan, Justin F. (2003). Local Government in Ireland: Inside Out. Dublin: Institute of Public Administration. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-902448-93-0.

- "Tipperary County Council: General News". 3 June 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

Tipperary County Council will become an official unified authority on 3 June 2014. The new authority combines the existing administration of North Tipperary County Council and South Tipperary County Council.

- "Electoral Act 1997: Part II, Section 6 (2)c". Irish Statute Book. Office of the Attorney General of Ireland. 15 May 1997. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- "Local Government Policy Division Structure". Department of the Environment, Northern Ireland. Archived from the original on 3 January 2008. Retrieved 30 January 2008.

- "Major reform of local government". bbc.co.ik, 22 November 2005. Retrieved on 23 January 2007.

- "Population of each Province, County and City, 2011". Principal Statistics. Central Statistics Office Ireland. Archived from the original on 6 March 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- "Provisional Population Statistics for New 11 Districts, 2011/2012" (PDF). Population Statistics. NISRA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- Abbot, Patrick. "Ireland's Peat Bogs". The Ireland Story. Retrieved 21 January 2008.

- "Blanket Bogs". Irish Peatland Conservation Council. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- "Raised Bogs". Irish Peatland Conservation Council. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- "Peat Energy History". Bord na Móna. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 21 January 2008.

- "Replacement of peat with Biomass in Electricity Generation". Feedstock. Bord na Móna. 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- "Written Answers. – Raised Bog Conservation". Dáil Éireann Parliamentary Debates – Volume 487. Office of the Houses of the Oireachtas. 26 February 1998. Retrieved 21 January 2008.

- Shannon, Corcoran & Haughton (2001), The petroleum exploration of Ireland's offshore basins: introduction, Geological Society, London Lyell Collection—Special Publications, p 2

- "Major petroleum exploration conference: Conference on Ireland's Deepwater Frontier". Department of Communications, Energy and Natural Resources. 16 September 2001. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- "History of the Corrib Project". Natural Resources. Department of Communications, Energy and Natural Resources. 2015. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- "Providence sees Helvick oil field as key site in Celtic Sea". Irish Examiner. 17 July 2000. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 27 January 2008.

- "Mining in Ireland". Minerals Ireland: Exploration and Mining Division. Department of Communications, Energy and Natural Resources. 2009. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- "Ireland on the verge of an oil and gas bonanza". Irish Independent. 20 May 2007. Retrieved 11 January 2008.

- Cresswell, Jeremy (1 October 2012). "Exxon to drill Irish Atlantic Frontier early next year". EnergyVoice. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- "Ireland's first oil well to yield 4,000 barrels per day". Northern Ireland. BBC News. 15 March 2012. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

Bibliography

Print

- Mitchell, Frank and Ryan, Michael. Reading the Irish landscape (1998). ISBN 1-86059-055-1

- Whittow, J. B. Geography and Scenery in Ireland (Penguin Books 1974)

- Holland, Charles, H and Sanders, Ian S. The Geology of Ireland 2nd ed. (2009). ISBN 1903765722

- Place-names, Diarmuid O Murchadha and Kevin Murray, in The Heritage of Ireland, ed. N. Buttimer et al., The Collins Press, Cork, 2000, pp. 146–155.

- A paper landscape:the Ordnance Survey in nineteenth-century Ireland, J.H. Andrews, London, 1975

- Monasticon Hibernicum, M. Archdall, 1786

- Etymological aetiology in Irish tradition, R. Baumgarten, Eiru 41, pp. 115–122, 1990

- The Origin and History of Irish names of Places, Patrick Weston Joyce, three volumes, Dublin, 1869, 1875, 1913.

- Irish Place Names, D. Flanagan and L. Flanagan, Dublin, 1994

- Census of Ireland:general alphabetical index to the townlands and towns, parishes and paronies of Ireland, Dublin, 1861

- The Placenames of Westmeath, Paul Walsh, 1957

- The Placenames of Decies, P. Power, Cork, 1952

- The place-names of county Wicklow, Liam Price, seven volumes, Dublin, 1945–67

Online

- Abbot, Patrick. Ireland's Peat Bogs. Retrieved on 23 January 2008.

- Ireland – The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved on 23 January 2008.

- OnlineWeather.com – climate details for Ireland. Retrieved 2011-01-12

External links

- OSI FAQ – lists of the longest, highest and other statistics

- A discussion on RTÉ Radio 1's science show Quantum Leap about the quality of GPS mapping in Ireland is available here (archived link). The discussion starts 8mins 17sec into the show. It was aired on 18 Jan 2007 (archived link). Requires RealPlayer.