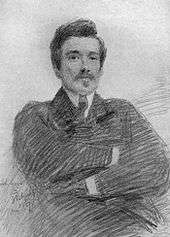

John Millington Synge

Edmund John Millington Synge (/sɪŋ/; 16 April 1871 – 24 March 1909) was an Irish playwright, poet, prose writer, travel writer and collector of folklore. He was a key figure in the Irish Literary Revival and was one of the co-founders of the Abbey Theatre. He is best known for his play The Playboy of the Western World, which caused riots in Dublin during its opening run at the Abbey Theatre.

John Millington Synge | |

|---|---|

John Millington Synge | |

| Born | Edmund John Millington Synge 16 April 1871 Rathfarnham, County Dublin, Ireland |

| Died | 24 March 1909 (aged 37) Elpis Nursing Home, Dublin, Ireland |

| Nationality | Irish |

| Occupation | Novelist, short story writer, playwright, poet, essayist |

| Known for | Drama, fictional prose |

| Movement | Folklore Irish Literary Revival |

Although he came from a privileged Anglo-Irish background, Synge's writings are mainly concerned with the world of the Catholic peasants of rural Ireland and with what he saw as the essential paganism of their world view. Synge developed Hodgkin's disease, a metastatic cancer that was then untreatable. He died several weeks short of his 38th birthday as he was trying to complete his last play, Deirdre of the Sorrows.

Biography

Early life

Synge was born in Newtown Villas, Rathfarnham, County Dublin, on 16 April 1871.[1] He was the youngest son in a family of eight children. His parents were members of the Protestant, upper middle class.[1] his father, John Hatch Synge, who was a barrister, came from a family of landed gentry in Glanmore Castle, County Wicklow. He was the uncle of brothers, mathematician John Lighton Synge and optical microscopy pioneer Edward Hutchinson Synge.[2] Synge's paternal grandfather, also named John Synge, was an evangelical Christian involved in the movement that became the Plymouth Brethren and his maternal grandfather, Robert Traill, had been a Church of Ireland rector in Schull, County Cork, who died in 1847 during the Great Irish Famine.His great, great grandfather was the archdeacon of killala [3]

Synge's father contracted smallpox and died in 1872 at the age of 49. He was buried on his son's first birthday. Synge's mother moved the family to the house next door to her mother's house in Rathgar, County Dublin. Synge, although often ill, had a happy childhood there. He developed an interest in bird-watching along the banks of the River Dodder[4] and during family holidays at the seaside resort of Greystones, County Wicklow, and the family estate at Glanmore.[5]

Synge was educated privately at schools in Dublin and Bray, and later studied piano, flute, violin, music theory and counterpoint at the Royal Irish Academy of Music. He travelled to the continent to study music, but changed his mind and decided to focus on literature.[1] He was a talented student and won a scholarship in counterpoint in 1891. The family moved to the suburb of Kingstown (now Dún Laoghaire) in 1888, and Synge entered Trinity College, Dublin the following year. He graduated with a bachelor's degree in 1892, having studied Irish and Hebrew, as well as continuing his music studies and playing with the Academy Orchestra in the Antient Concert Rooms.[6] Between November 1889 and 1894 he took private music lessons with Robert Prescott Stewart.[7]

Synge joined the Dublin Naturalists' Field Club and read the works of Charles Darwin.[1] He wrote: "When I was about 14, I obtained a book of Darwin's .... My studies showed me the force of what I read, [and] the more I put it from me the more it rushed back with new instances and power ... Soon afterwards I turned my attention to works of Christian evidence, reading them at first with pleasure, soon with doubt, and at last in some cases with derision."[8] He then continued, "Soon after I had relinquished the kingdom of God I began to take up a real interest in the kingdom of Ireland. My politics went round ... to a temperate Nationalism."[9]

Synge later developed an interest in Irish antiquities and the Aran Islands, and became a member of the Irish League for a year.[10] He left the League because, as he told Maud Gonne, "my theory of regeneration for Ireland differs from yours ... I wish to work on my own for the cause of Ireland, and I shall never be able to do so if I get mixed up with a revolutionary and semi-military movement."[11] In 1893 he published his first known work, a poem influenced by Wordsworth, Kottabos: A College Miscellany.

Emerging writer

After graduating, Synge decided that he wanted to be a professional musician and went to Germany to study music. He stayed in Coblenz during 1893 and moved to Würzburg in January 1894.[12] Partly because he was shy about performing in public, and partly because of doubt about his ability, he decided to abandon music and pursue his literary interests. He returned to Ireland in June 1894, and moved to Paris in January 1895 to study literature and languages at the Sorbonne.[13]

During summer holidays with his family in Dublin he met and fell in love with Cherrie Matheson, a friend of one of his cousins and a member of the Plymouth Brethren. He proposed to her in 1895 and again the next year, but she turned him down on both occasions because of their differing views on religion. This rejection affected Synge greatly and reinforced his determination to spend as much time as possible outside Ireland.[14]

In 1896, Synge visited Italy to study the language for a time before returning to Paris. Later that year he met W. B. Yeats, who encouraged him to live for a while in the Aran Islands, and then return to Dublin and devote himself to creative work. That year he joined with Yeats, Augusta, Lady Gregory, and George William Russell to form the Irish National Theatre Society, which later established the Abbey Theatre.[10] He also wrote some pieces of literary criticism for Gonne's Irlande Libre and other journals, as well as unpublished poems and prose in a decadent fin de siècle style.[15] (These writings were eventually gathered in the 1960s for his Collected Works.)[16] He also attended lectures at the Sorbonne by the noted Celtic scholar Henri d'Arbois de Jubainville.[17]

Aran Islands and first plays

.jpg)

A resident of the island of Inishmaan

In 1897, Synge had his first attack of Hodgkin's disease and had an enlarged gland removed from his neck.[18] The following year he spent the summer in the Aran Islands.[19] He spent the next five summers in the Aran Islands, collecting stories and folklore, and perfecting his Irish, while continuing to live in Paris for most of the rest of each year.[20] He also visited Brittany regularly.[21] During this period he wrote his first play, When the Moon Has Set and sent it to Lady Gregory for the Irish Literary Theatre in 1900, but she rejected it. (The play was not published until it appeared in the Collected Works.)[22]

Synge's first account of life in the Aran Islands was published in the New Ireland Review in 1898 and his book, The Aran Islands, based largely on journals, was completed in 1901 and published in 1907 with illustrations by Jack Butler Yeats.[1] Synge considered the book "my first serious piece of work".[1] When Lady Gregory read the manuscript she advised Synge to remove any direct naming of places and to add more folk stories, but he refused to do either because he wanted to create something more realistic.[23] The book expresses Synge's belief that beneath the Catholicism of the islanders it was possible to detect a substratum of the pagan beliefs of their ancestors. His experiences in the Aran Islands were to form the basis for the plays about Irish rural life that Synge went on to write.[24]

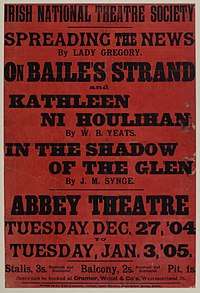

In 1903 Synge left Paris and moved to London. He had written two one-act plays, Riders to the Sea and The Shadow of the Glen, the previous year. These met with Lady Gregory's approval and The Shadow of the Glen was performed at the Molesworth Hall in October 1903.[25] Riders to the Sea was performed at the same venue in February the following year. The Shadow of the Glen, under the title In the Shadow of the Glen, formed part of the bill for the opening run of the Abbey Theatre from 27 December 1904 to 3 January 1905.[25] Both plays were based on stories that Synge had collected in the Aran Islands, and Synge relied on props from the Aran Islands to help set the stage for each of them.[25] He also relied on Hiberno-English, the English dialect of Ireland, to reinforce its usefulness as a literary language, partly because he believed that the Irish language could not survive.[26]

The Shadow of the Glen, based on a story about an unfaithful wife, was attacked in print by the Irish nationalist leader Arthur Griffith as "a slur on Irish womanhood".[26] Years later Synge wrote: "When I was writing The Shadow of the Glen some years ago I got more aid than any learning could have given me from a chink in the floor of the old Wicklow house where I was staying, that let me hear what was being said by the servant girls in the kitchen."[27] This encouraged more critical attacks alleging that Synge described Irish women in an unfair manner.[26] Riders to the Sea was also attacked by nationalists, this time including Patrick Pearse, who decried it because of the author's attitude to God and religion. Pearse, Arthur Griffith and other conservative-minded Catholics claimed Synge had done a disservice to Irish nationalism by not idealising his characters.[28] However, later critics have attacked Synge for idealising the Irish peasantry too much.[28] A third one-act play, The Tinker's Wedding, was drafted around this time, but Synge initially made no attempt to have it performed, largely because of a scene in which a priest is tied up in a sack, which, as he wrote to the publisher Elkin Mathews in 1905, would probably upset "a good many of our Dublin friends".[29]

When the Abbey Theatre was set up, Synge was appointed literary adviser and became one of the directors, along with Yeats and Lady Gregory. He differed from Yeats and Lady Gregory on what he believed the Irish theatre should be, as he wrote to Stephen MacKenna:

I do not believe in the possibility of "a purely fantastic, unmodern, ideal, breezy, spring-dayish, Cuchulainoid National Theatre" ... no drama can grow out of anything other than the fundamental realities of life, which are never fantastic, are neither modern nor unmodern and, as I see them, rarely spring-dayish, or breezy or Cuchulanoid.[30]

Synge's next play, The Well of the Saints, was staged at the Abbey in 1905, again to nationalist disapproval, and then in 1906 at the Deutsches Theater in Berlin.[31] The critic Joseph Holloway claimed that the play combined "lyric and dirt".[32]

Playboy riots and after

The play widely regarded as Synge's masterpiece, The Playboy of the Western World, was first performed at the Abbey Theatre on 26 January 1907. A comedy about apparent patricide, it attracted a hostile reaction from sections of the Irish public. The Freeman's Journal described it as "an unmitigated, protracted libel upon Irish peasant men, and worse still upon Irish girlhood".[33] Arthur Griffith, who believed that the Abbey Theatre was insufficiently politically committed, described the play as "a vile and inhuman story told in the foulest language we have ever listened to from a public platform", and perceived a slight on the virtue of Irish womanhood in the line "... a drift of chosen females, standing in their shifts ..."

At the time, a shift was known as a symbol representing Kitty O'Shea and adultery.[34] A significant portion of the audience at the first performance rioted, causing the third act of the play to be acted out in dumbshow.[35] Riots continued at each of the scheduled performances that week. Yeats referred to this incident in a speech to the Abbey audience in 1926 on the fourth night of Seán O'Casey's The Plough and the Stars, when he declared: "You have disgraced yourselves again. Is this to be an ever-recurring celebration of the arrival of Irish genius? Synge first and then O'Casey?"[36]

Although the writing of The Tinker's Wedding began at the same time as Riders to the Sea and In the Shadow of the Glen, it took Synge five years to complete, and was finished in 1907.[29] Riders was performed in the Racquet Court theatre in Galway 4–8 January 1907 and not performed again until 1909, and only then in London. The first critic to respond to the play was Daniel Corkery, who said, "One is sorry Synge ever wrote so poor a thing, and one fails to understand why it ever should have been staged anywhere."[37]

Death

Synge died at the Elpis Nursing Home in Dublin on 24 March 1909, aged 37, and was buried in Mount Jerome Cemetery, Harold's Cross, Dublin.

A collected volume, Poems and Translations, with a preface by Yeats, was published by the Cuala Press on 8 April 1909. Yeats and actress and one-time fiancée Molly Allgood (Maire O'Neill) completed Synge's unfinished final play, Deirdre of the Sorrows, and it was presented by the Abbey players on Thursday 13 January 1910 with Allgood as Deirdre.[28]

Personality

John Masefield, who knew Synge, wrote that he "gave one from the first the impression of a strange personality".[38] Masefield said that Synge's view of life originated in his poor health. In particular, Masefield said "His relish of the savagery made me feel that he was a dying man clutching at life, and clutching most wildly at violent life, as the sick man does".[39]

Yeats summarised his view of Synge in one of the stanzas of his poem "In Memory of Major Robert Gregory":

- And that enquiring man John Synge comes next,

- That dying chose the living world for text

- And never could have rested in the tomb

- But that, long travelling, he had come

- Towards nightfall upon certain set apart

- In a most desolate stony place,

- Towards nightfall upon a race

- Passionate and simple like his heart.

Synge was a political radical, immersed in the socialist literature of William Morris, and in his own words "wanted to change things root and branch."[40] Much to the consternation of his mother, he went to Paris in 1896 to become more involved in radical politics, and his interest in the topic lasted until his dying days when he sought to engage his nurses on the topic of feminism.[40]

Legacy

Synge's plays helped to set the dominant style of plays at the Abbey Theatre until the 1940s. The stylised realism of his writing was reflected in the training given at the theatre's school of acting, and plays of peasant life were the main staple of the repertoire until the end of the 1950s. Sean O'Casey, the next major dramatist to write for the Abbey, knew Synge's work well and attempted to do for the Dublin working classes what Synge had done for the rural poor. Brendan Behan, Brinsley MacNamara, and Lennox Robinson were all indebted to Synge.[41]

Critic Vivian Mercier was among the first to recognise Samuel Beckett's debt to Synge.[42] Beckett was a regular member of the audience at the Abbey in his youth and particularly admired the plays of Yeats, Synge and O'Casey. Mercier points out parallels between Synge's casts of tramps, beggars and peasants and many of the figures in Beckett's novels and dramatic works.[43]

In recent years. Synge's cottage in the Aran Islands has been restored as a tourist attraction. An annual Synge Summer School has been held every summer since 1991 in the village of Rathdrum, County Wicklow.[44] Synge is the subject of Mac Dara Ó Curraidhín's 1999 documentary film, Synge agus an Domhan Thiar (Synge and the Western World). Joseph O'Connor wrote a novel, Ghost Light (2010), loosely based on Synge's relationship with Molly Allgood.[45][46]

Works

- In the Shadow of the Glen, 1903

- Riders to the Sea, 1904

- The Well of the Saints, 1905

- The Aran Islands, 1907 (The book at wikisource: The Aran Islands)

- The Playboy of the Western World, 1907

- The Tinker's Wedding, 1908

- Poems and Translations, 1909

- Deirdre of the Sorrows 1910

- In Wicklow and West Kerry, 1912

- Collected Works of John Millington Synge 4 vols, 1962–1968

- Volume 1 Poems, 1962

- Volume 2 Prose, 1966

- Volumes 3 and 4 Plays, 1968

Notes

- Smith 1996 xiv

- Review of The Life and Works of Edward Hutchinson Synge Living Edition

- W. J. McCormack, "Synge, (Edmund) John Millington (1871–1909)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2010 accessed 20 March 2017

- Greene and Stephens 1959, pp. 4–5

- Greene and Stephens 1959, p. 6

- Greene and Stephens 1959, pp. 16–19, 26

- Parker, Lisa: Robert Prescott Stewart (1825–1894): A Victorian Musician in Dublin (Ph.D. thesis, NUI Maynooth, 2009), unpublished.

- Synge 1982, pp. 10–11

- Synge 1982, p. 13

- Smith 1996 xv

- Greene and Stephens 1959, pp. 62–63

- Greene and Stephens 1959, 35

- Greene and Stephens 1959, pp. 43–47

- Greene and Stephens 1959, pp. 48–52

- Greene and Stephens 1959, 60

- Price 1972, 292

- Greene and Stephens 1959, p. 72

- Greene and Stephens 1959, p. 70

- He also spent time at Lady Gregory's home, Coole Park near Gort, County Galway, where he met Yeats again and also Edward Martyn.

- Greene and Stephens 1959, pp. 74–88

- Greene and Stephens 1959, p. 95

- Price 1972, p. 293

- Smith 1996, xvi

- Greene and Stephens 1959, pp. 96–99

- Smith 1996, xvii

- Smith 1996, xxiv

- Synge "Preface" to The Playboy

- Smith 1996, xiii

- Smith 1996, xviii

- Greene and Stephens 1959, p. 157

- Smith 1996, xix

- Hogan and O'Neill 1967, p. 53

- Ferriter 2004, pp. 94–95

- Price 1961, pp. 15, 25

- Isherwood 2004

- Gassner 2002, p. 468

- Corkery 1931, p. 152

- Masefield 1916, p. 6

- Masefield 1916, p. 22

- Kiberd, Declan (1997). Inventing Ireland. Harvard University Press. p. 175.

- Greene 1994, p. 26

- Mercier 1977, p. 23

- Mercier 1977, pp. 20–23

- Irish Theatre and the World Stage Archived 2 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine, SyngeSummerSchool.org; retrieved 27 August 2008.

- "Ghost Light by Joseph O'Connor". Josephoconnorauthor.com. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- "Brimming with sympathy and skill". The Irish Times. 29 May 2010. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

References

- Mary Burke, 'Tinkers': Synge and the Cultural History of the Irish Traveller (Oxford, OUP, 2009).

- Corkery, Daniel. Synge and Anglo-Irish Literature. Cork University Press, 1931.

- Ferriter, Diarmaid (2004). The Transformation of Ireland 1900–2000. Profile Books. pp. 94–95. ISBN 1-86197-307-1.

- Gassner, John & Quinn, Edward. "The Reader's Encyclopedia of World Drama". Dover Publications, May 2002. ISBN 0-486-42064-7

- Greene, David H. & Stephens, Edward M. "J.M. Synge 1871–1909" (The MacMillan Company New York 1959)

- Greene, David. "J.M. Synge: A Reappraisal" in Critical Essays on John Millington Synge, ed. Daniel J. Casey, 15–27. New York: G. K. Hall & Co., 1994.

- Hogan, Robert and O'Neill, Michael. Joseph Holloway's Abbey Theatre. Carbondale, Southern Illinois University Press, 1967.

- Isherwood, Charles. "A Seductive Fellow Returns, but in a Darker Mood". New York Times, 28 October 2004.

- Masefield, John. John M. Synge: A Few Personal Recollections With Biographical Notes, Netchworth: Garden City Press Ltd., 1916.

- Mercier, Vivian. Beckett/Beckett. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977. ISBN 0-19-281269-6

- Price, Alan. "Synge and Anglo-Irish Drama". London: Methuen, 1961.

- Price, Alan. "A Survey of Recent Work on J. M. Synge" in A Centenary Tribute to J. M. Synge 1871–1909. Ed. S. B. Bushrui. New York: Barnes & Noble, 1972. ISBN 0-389-04567-5.

- Smith, Alison. "Introduction" in Collected Plays, Poems, and The Aran Islands. Edited by Alison Smith. London: Everyman, 1996.

- Synge, John Millington. Collected Works. Edited by Robin Skelton, Alan Price, and Ann Saddlemeyer. Gerrards Cross: Smythe, 1982. ISBN 0-86140-058-5

- Watson, George. Irish Identity and the Literary Revival. London: Croom Helm, 1979.

Further reading

- Igoe, Vivien. A Literary Guide to Dublin. (Methuen, 1994) ISBN 0-413-69120-9

- Johnston, Denis. John Millington Synge, (Columbia Essays on Modern Writing No. 12), (Columbia Univ. Press, New York, 1965)

- Kiberd, Declan. Synge and the Irish Language. (Rowman and Littlefield, 1979)

- Kiely, David M. John Millington Synge: A Biography (New York, St. Martin's Press, 1994) ISBN 0-312-13526-2

- Kopper, Edward A. (ed.). A J.M. Synge Literary Companion. (Greenwood, 1988)

- McCormack, W. J. Fool of the Family: A Life of J. M. Synge (New York University Press, 2001) ISBN 0-8147-5652-2

- Ryan, Philip B. The Lost Theatres of Dublin. (The Badger Press, 1998) ISBN 0-9526076-1-1

- Synge, J. M. The Complete Plays. 1st. New York: Vintage Books, 1935.

- Synge, J. M."The Aran Islands" edited with an introduction by Tim Robinson (Penguin 1992) ISBN 0-14-018432-5

- Irish Writers on Writing featuring John Millington Synge. Edited by Eavan Boland (Trinity University Press, 2007).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John Millington Synge. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: John Millington Synge |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: John Millington Synge |

- Works by John Millington Synge at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about John Millington Synge at Internet Archive

- Works by John Millington Synge at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- "Archival material relating to John Millington Synge". UK National Archives.

- Portraits of John Millington Synge at the National Portrait Gallery, London