James Joyce

James Augustine[1] Aloysius Joyce (2 February 1882 – 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist, short story writer, poet, teacher, and literary critic. He contributed to the modernist avant-garde movement and is regarded as one of the most influential and important writers of the 20th century. Joyce is best known for Ulysses (1922), a landmark work in which the episodes of Homer's Odyssey are paralleled in a variety of literary styles, most famously stream of consciousness. Other well-known works are the short-story collection Dubliners (1914), and the novels A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916) and Finnegans Wake (1939). His other writings include three books of poetry, a play, his published letters and occasional journalism.

James Joyce | |

|---|---|

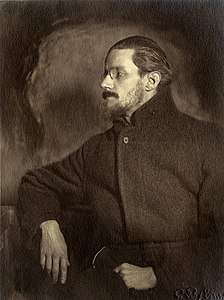

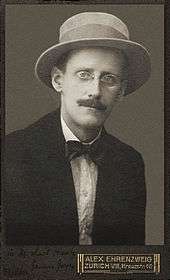

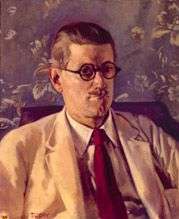

Joyce in Zürich, c. 1918 | |

| Born | James Augustine Aloysius Joyce 2 February 1882 Rathgar, Dublin, Ireland |

| Died | 13 January 1941 (aged 58) Zürich, Switzerland |

| Resting place | Fluntern Cemetery, Zürich |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Language | English |

| Residence | Trieste, Paris, Zürich |

| Nationality | Irish |

| Citizenship | Irish |

| Alma mater | University College Dublin |

| Period | 1914–1939 |

| Genre | Novels, Short stories, Poetry |

| Literary movement | Modernism |

| Notable works | Dubliners Ulysses A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man Finnegans Wake |

| Years active | 1904–1940 |

| Spouse | Nora Barnacle (1931 – his death) |

| Children | Lucia, Giorgio |

| Signature | |

Joyce was born in Dublin into a middle-class family. A brilliant student, he briefly attended the Christian Brothers-run O'Connell School before excelling at the Jesuit schools Clongowes and Belvedere, despite the chaotic family life imposed by his father's unpredictable finances. He went on to attend University College Dublin.

In 1904, in his early twenties, Joyce emigrated to continental Europe with his partner (and later wife) Nora Barnacle. They lived in Trieste, Paris, and Zürich. Although most of his adult life was spent abroad, Joyce's fictional universe centres on Dublin and is populated largely by characters who closely resemble family members, enemies and friends from his time there. Ulysses in particular is set with precision in the streets and alleyways of the city. Shortly after the publication of Ulysses, he elucidated this preoccupation somewhat, saying, "For myself, I always write about Dublin, because if I can get to the heart of Dublin I can get to the heart of all the cities of the world. In the particular is contained the universal."[2]

Early life

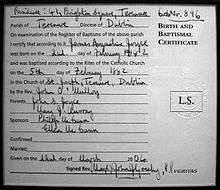

On 2 February 1882, Joyce was born at 41 Brighton Square, Rathgar, Dublin, Ireland.[3] Joyce's father was John Stanislaus Joyce and his mother was Mary Jane "May" Murray. He was the eldest of ten surviving siblings; two died of typhoid. James was baptised according to the Rites of the Catholic Church in the nearby St Joseph's Church in Terenure on 5 February 1882 by Rev. John O'Mulloy. Joyce's godparents were Philip and Ellen McCann.

John Stanislaus Joyce's family came from Fermoy in County Cork, and had owned a small salt and lime works. Joyce's paternal grandfather, James Augustine Joyce, married Ellen O'Connell, daughter of John O'Connell, a Cork Alderman who owned a drapery business and other properties in Cork City. Ellen's family claimed kinship with Daniel O'Connell, "The Liberator".[4] The Joyce family's purported ancestor, Seán Mór Seoighe (fl. 1680) was a stonemason from Connemara.[5]

In 1887, his father was appointed rate collector by Dublin Corporation; the family subsequently moved to the fashionable adjacent small town of Bray, 12 miles (19 km) from Dublin. Around this time Joyce was attacked by a dog, leading to his lifelong cynophobia. He suffered from astraphobia; a superstitious aunt had described thunderstorms as a sign of God's wrath.[6]

In 1891 Joyce wrote a poem on the death of Charles Stewart Parnell. His father was angry at the treatment of Parnell by the Catholic Church, the Irish Home Rule Party and the British Liberal Party and the resulting collaborative failure to secure Home Rule for Ireland. The Irish Party had dropped Parnell from leadership. But the Vatican's role in allying with the British Conservative Party to prevent Home Rule left a lasting impression on the young Joyce.[7] The elder Joyce had the poem printed and even sent a part to the Vatican Library. In November, John Joyce was entered in Stubbs' Gazette (a publisher of bankruptcies) and suspended from work. In 1893, John Joyce was dismissed with a pension, beginning the family's slide into poverty caused mainly by his drinking and financial mismanagement.[8]

Joyce had begun his education at Clongowes Wood College, a Jesuit boarding school near Clane, County Kildare, in 1888 but had to leave in 1892 when his father could no longer pay the fees. Joyce then studied at home and briefly at the Christian Brothers O'Connell School on North Richmond Street, Dublin, before he was offered a place in the Jesuits' Dublin school, Belvedere College, in 1893. This came about because of a chance meeting his father had with a Jesuit priest called John Conmee who knew the family and Joyce was given a reduction in fees to attend Belvedere.[9] In 1895, Joyce, now aged 13, was elected to join the Sodality of Our Lady by his peers at Belvedere.[10] The philosophy of Thomas Aquinas continued to have a strong influence on him for most of his life.[11]

Education

Joyce enrolled at the recently established University College Dublin (UCD) in 1898, studying English, French and Italian. He became active in theatrical and literary circles in the city. In 1900 his laudatory review of Henrik Ibsen's When We Dead Awaken was published in The Fortnightly Review; it was his first publication and, after learning basic Norwegian to send a fan letter to Ibsen, he received a letter of thanks from the dramatist. Joyce wrote a number of other articles and at least two plays (since lost) during this period. Many of the friends he made at University College Dublin appeared as characters in Joyce's works. His closest colleagues included leading figures of the generation, most notably, Tom Kettle, Francis Sheehy-Skeffington and Oliver St. John Gogarty. Joyce was first introduced to the Irish public by Arthur Griffith in his newspaper, United Irishman, in November 1901. Joyce had written an article on the Irish Literary Theatre and his college magazine refused to print it. Joyce had it printed and distributed locally. Griffith himself wrote a piece decrying the censorship of the student James Joyce.[12][13] In 1901, the National Census of Ireland lists James Joyce (19) as an English- and Irish-speaking scholar living with his mother and father, six sisters and three brothers at Royal Terrace (now Inverness Road), Clontarf, Dublin.[14]

After graduating from UCD in 1902, Joyce left for Paris to study medicine, but he soon abandoned this. Richard Ellmann suggests that this may have been because he found the technical lectures in French too difficult. Joyce had already failed to pass chemistry in English in Dublin. But Joyce claimed ill health as the problem and wrote home that he was unwell and complained about the cold weather.[15] He stayed on for a few months, appealing for finance his family could ill-afford and reading late in the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève. When his mother was diagnosed with cancer, his father sent a telegram which read, "NOTHER [sic] DYING COME HOME FATHER".[16] Joyce returned to Ireland. Fearing for her son's impiety, his mother tried unsuccessfully to get Joyce to make his confession and to take communion. She finally passed into a coma and died on 13 August, James and his brother Stanislaus having refused to kneel with other members of the family praying at her bedside.[17] After her death he continued to drink heavily, and conditions at home grew quite appalling. He scraped together a living reviewing books, teaching, and singing—he was an accomplished tenor, and won the bronze medal in the 1904 Feis Ceoil.[18][19]

Career

On 7 January 1904, Joyce attempted to publish A Portrait of the Artist, an essay-story dealing with aesthetics, only to have it rejected by the free-thinking magazine Dana. He decided, on his twenty-second birthday, to revise the story into a novel he called Stephen Hero. It was a fictional rendering of Joyce's youth, but he eventually grew frustrated with its direction and abandoned this work. It was never published in this form, but years later, in Trieste, Joyce completely rewrote it as A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. The unfinished Stephen Hero was published after his death.[20]

Also in 1904, he met Nora Barnacle, a young woman from Galway city who was working as a chambermaid. On 16 June 1904 they had their first outing together, walking to the Dublin suburb of Ringsend, where Nora masturbated him. This event was commemorated by providing the date for the action of Ulysses (as "Bloomsday").[21]

Joyce remained in Dublin for some time longer, drinking heavily. After one of his drinking binges, he got into a fight over a misunderstanding with a man in St Stephen's Green;[22] he was picked up and dusted off by a minor acquaintance of his father, Alfred H. Hunter, who took him into his home to tend to his injuries.[23] Hunter was rumoured to be a Jew and to have an unfaithful wife and would serve as one of the models for Leopold Bloom, the protagonist of Ulysses.[24] He took up with the medical student Oliver St. John Gogarty, who informed the character for Buck Mulligan in Ulysses. After six nights in the Martello Tower that Gogarty was renting in Sandycove, he left in the middle of the night following an altercation which involved another student he lived with, the unstable Dermot Chenevix Trench (Haines in Ulysses), who fired a pistol at some pans hanging directly over Joyce's bed.[25] Joyce walked the 8 miles (13 km) back to Dublin to stay with relatives for the night, and sent a friend to the tower the next day to pack his trunk. Shortly after, the couple left Ireland to live on the continent.

1904–20: Trieste and Zürich

Joyce and Nora went into self-imposed exile, moving first to Zürich in Switzerland, where he ostensibly taught English at the Berlitz Language School through an agent in England. It later became evident that the agent had been swindled; the director of the school sent Joyce on to Trieste, which was then part of Austria-Hungary (until the First World War), and is today part of Italy. Once again, he found there was no position for him, but with the help of Almidano Artifoni, director of the Trieste Berlitz School, he finally secured a teaching position in Pola, then also part of Austria-Hungary (today part of Croatia). He stayed there, teaching English mainly to Austro-Hungarian naval officers stationed at the Pola base, from October 1904 until March 1905, when the Austrians—having discovered an espionage ring in the city—expelled all aliens. With Artifoni's help, he moved back to Trieste and began teaching English there. He remained in Trieste for most of the next ten years.[26][27]

Later that year Nora gave birth to their first child, George (known as Giorgio). Joyce persuaded his brother, Stanislaus, to join him in Trieste, and secured a teaching position for him at the school. Joyce sought to augment his family's meagre income with his brother's earnings.[28] Stanislaus and Joyce had strained relations while they lived together in Trieste, arguing about Joyce's drinking habits and frivolity with money.[29]

Joyce became frustrated with life in Trieste and moved to Rome in late 1906, taking employment as a clerk in a bank. He disliked Rome and returned to Trieste in early 1907. His daughter Lucia was born later that year.[30]

Joyce returned to Dublin in mid-1909 with George, to visit his father and work on getting Dubliners published. He visited Nora's family in Galway and liked Nora's mother very much.[31] While preparing to return to Trieste he decided to take one of his sisters, Eva, back with him to help Nora run the home. He spent a month in Trieste before returning to Dublin, this time as a representative of some cinema owners and businessmen from Trieste. With their backing he launched Ireland's first cinema, the Volta Cinematograph, which was well-received, but fell apart after Joyce left. He returned to Trieste in January 1910 with another sister, Eileen, in tow.[32] Eva became homesick for Dublin and returned there a few years later, but Eileen spent the rest of her life on the continent, eventually marrying the Czech bank cashier Frantisek Schaurek.[33]

Joyce returned to Dublin again briefly in mid-1912 during his years-long fight with Dublin publisher George Roberts over the publication of Dubliners. His trip was once again fruitless, and on his return he wrote the poem "Gas from a Burner", an invective against Roberts. After this trip, he never again came closer to Dublin than London, despite many pleas from his father and invitations from his fellow Irish writer William Butler Yeats.

One of his students in Trieste was Ettore Schmitz, better known by the pseudonym Italo Svevo. They met in 1907 and became lasting friends and mutual critics. Schmitz was a Catholic of Jewish origin and became a primary model for Leopold Bloom; most of the details about the Jewish faith in Ulysses came from Schmitz's responses to queries from Joyce.[34] While living in Trieste, Joyce was first beset with eye problems that ultimately required over a dozen surgical operations.[35]

Joyce concocted a number of money-making schemes during this period, including an attempt to become a cinema magnate in Dublin. He frequently discussed but ultimately abandoned a plan to import Irish tweed to Trieste. Correspondence relating to that venture with the Irish Woollen Mills were for a long time displayed in the windows of their premises in Dublin. Joyce's skill at borrowing money saved him from indigence. What income he had came partially from his position at the Berlitz school and partially from teaching private students.

In 1915, after most of his students in Trieste were conscripted to fight in the Great War, Joyce moved to Zürich. Two influential private students, Baron Ambrogio Ralli and Count Francesco Sordina, petitioned officials for an exit permit for the Joyces, who in turn agreed not to take any action against the emperor of Austria-Hungary during the war.[36]

During this period Joyce took an active interest in socialism.[37] He had attended socialist meetings when he was still in Dublin and 1905, while in Trieste, he described his politics as "those of a socialist artist."[37] Although his practical engagement waned after 1907 due to the "endless internecine warfare" he observed in socialist organizations, many Joyce scholars such as Richard Ellmann, Dominic Manganiello, Robert Scholes, and George J. Watson agree that Joyce's interest in socialism and pacifistic anarchism continued for much of his life, and that both the form and content of Joyce's work reflect a sympathy for democratic and socialist ideas.[38][39][40] In 1918 he declared himself "against every state"[39] and found much succor in the individualist philosophies of Benjamin Tucker and Oscar Wilde's The Soul of Man Under Socialism.[40] Later in the 1930s, Joyce rated his experiences with the defeated multi-ethnic Habsburg Empire as: "They called the Empire a ramshackle empire, I wish to God there were more such empires."[41]

1920–41: Paris and Zürich

Joyce set himself to finishing Ulysses in Paris, delighted to find that he was gradually gaining fame as an avant-garde writer. A further grant from Harriet Shaw Weaver meant he could devote himself full-time to writing again, as well as consort with other literary figures in the city. During this time, Joyce's eyes began to give him more and more problems and he often wore an eyepatch. He was treated by Louis Borsch in Paris, undergoing nine operations before Borsch's death in 1929.[42] Throughout the 1930s he travelled frequently to Switzerland for eye surgeries and for treatments for his daughter Lucia, who, according to the Joyces, suffered from schizophrenia. Lucia was analysed by Carl Jung at the time, who after reading Ulysses is said to have concluded that her father had schizophrenia.[43] Jung said that she and her father were two people heading to the bottom of a river, except that Joyce was diving and Lucia was sinking.[44][45][46]

In Paris, Maria and Eugene Jolas nursed Joyce during his long years of writing Finnegans Wake. Were it not for their support (along with Harriet Shaw Weaver's constant financial support), there is a good possibility that his books might never have been finished or published. In their literary magazine transition, the Jolases published serially various sections of Finnegans Wake under the title Work in Progress. Joyce returned to Zürich in late 1940, fleeing the Nazi occupation of France. Joyce used his contacts to help some sixteen Jews escape Nazi persecution.[47]

Joyce and religion

The issue of Joyce's relationship with religion is somewhat controversial. Early in life, he lapsed from Catholicism, according to first-hand testimonies coming from himself, his brother Stanislaus Joyce, and his wife:

My mind rejects the whole present social order and Christianity—home, the recognised virtues, classes of life and religious doctrines. ... Six years ago I left the Catholic church, hating it most fervently. I found it impossible for me to remain in it on account of the impulses of my nature. I made secret war upon it when I was a student and declined to accept the positions it offered me. By doing this I made myself a beggar but I retained my pride. Now I make open war upon it by what I write and say and do.[48][49]:3

When the arrangements for Joyce's burial were being made, a Catholic priest offered a religious service, which Joyce's wife, Nora, declined, saying, "I couldn't do that to him."[50]

Leonard Strong, William T. Noon, Robert Boyle and others have argued that Joyce, later in life, reconciled with the faith he rejected earlier in life and that his parting with the faith was succeeded by a not so obvious reunion, and that Ulysses and Finnegans Wake are essentially Catholic expressions.[51] Likewise, Hugh Kenner and T. S. Eliot believed they saw between the lines of Joyce's work the outlook of a serious Christian and that beneath the veneer of the work lies a remnant of Catholic belief and attitude.[52] Kevin Sullivan maintains that, rather than reconciling with the faith, Joyce never left it.[53] Critics holding this view insist that Stephen, the protagonist of the semi-autobiographical A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man as well as Ulysses, is not Joyce.[53] Somewhat cryptically, in an interview after completing Ulysses, in response to the question "When did you leave the Catholic Church", Joyce answered, "That's for the Church to say."[54] Eamonn Hughes maintains that Joyce takes a dialectic approach, both affirming and denying, saying that Stephen's much noted non-serviam is qualified—"I will not serve that which I no longer believe...", and that the non-serviam will always be balanced by Stephen's "I am a servant..." and Molly's "yes".[55] He attended Catholic Mass and Orthodox Divine Liturgy, especially during Holy Week, purportedly for aesthetic reasons.[56] His sisters noted his Holy Week attendance and that he did not seek to dissuade them.[56] One friend reported that Joyce cried "secret tears" upon hearing Jesus' words on the cross and another suggested that he was a "believer at heart" because of his frequent attendance at church.[56]

Umberto Eco compares Joyce to the ancient episcopi vagantes (wandering bishops) in the Middle Ages. They left a discipline, not a cultural heritage or a way of thinking. Like them, the writer retains the sense of blasphemy held as a liturgical ritual.[57]

Some critics and biographers have opined along the lines of Andrew Gibson: "The modern James Joyce may have vigorously resisted the oppressive power of Catholic tradition. But there was another Joyce who asserted his allegiance to that tradition, and never left it, or wanted to leave it, behind him." Gibson argues that Joyce "remained a Catholic intellectual if not a believer" since his thinking remained influenced by his cultural background, even though he lived apart from that culture.[58] His relationship with religion was complex and not easily understood, even perhaps by himself. He acknowledged the debt he owed to his early Jesuit training. Joyce told the sculptor August Suter, that from his Jesuit education, he had 'learnt to arrange things in such a way that they become easy to survey and to judge.'[59]

Death

On 11 January 1941, Joyce underwent surgery in Zürich for a perforated duodenal ulcer. He fell into a coma the following day. He awoke at 2 a.m. on 13 January 1941, and asked a nurse to call his wife and son, before losing consciousness again. They were en route when he died 15 minutes later. Joyce was less than a month short of his 59th birthday.[60]

His body was buried in the Fluntern Cemetery, Zürich. The Swiss tenor Max Meili sang Addio terra, addio cielo from Monteverdi's L'Orfeo at the burial service.[61] Although two senior Irish diplomats were in Switzerland at the time, neither attended Joyce's funeral, and the Irish government later declined Nora's offer to permit the repatriation of Joyce's remains. When Joseph Walshe, secretary at the Department of External Affairs in Dublin, was informed of Joyce's death by Frank Cremins, chargé d'affaires at Bern, Walshe responded "Please wire details of Joyce's death. If possible find out did he die a Catholic? Express sympathy with Mrs Joyce and explain inability to attend funeral".[62] Buried originally in an ordinary grave, Joyce was moved in 1966 to a more prominent "honour grave," with a seated portrait statue by American artist Milton Hebald nearby. Nora, whom he had married in 1931, survived him by 10 years. She is buried by his side, as is their son Giorgio, who died in 1976.[62]

In October 2019 a motion was put to Dublin City Council to plan and budget for the costs of the exhumations and reburials of Joyce and his family somewhere in Dublin, subject to his family's wishes.[63] The proposal immediately became controversial, with the Irish Times commenting: "...it is hard not to suspect that there is a calculating, even mercantile, aspect to contemporary Ireland's relationship to its great writers, whom we are often more keen to 'celebrate', and if possible monetise, than read".[64]

Major works

Dubliners

Dubliners is a collection of fifteen short stories by Joyce, first published in 1914.[65] They form a naturalistic depiction of Irish middle-class life in and around Dublin in the early years of the 20th century.

The stories were written when Irish nationalism was at its peak and a search for a national identity and purpose was raging; at a crossroads of history and culture, Ireland was jolted by converging ideas and influences. The stories centre on Joyce's idea of an epiphany: a moment when a character experiences a life-changing self-understanding or illumination. Many of the characters in Dubliners later appear in minor roles in Joyce's novel Ulysses.[66] The initial stories in the collection are narrated by child protagonists. Subsequent stories deal with the lives and concerns of progressively older people. This aligns with Joyce's tripartite division of the collection into childhood, adolescence and maturity.

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man is a nearly complete rewrite of the abandoned novel Stephen Hero. Joyce attempted to burn the original manuscript in a fit of rage during an argument with Nora, though to his subsequent relief it was rescued by his sister. A Künstlerroman, Portrait is a heavily autobiographical[67] coming-of-age novel depicting the childhood and adolescence of the protagonist Stephen Dedalus and his gradual growth into artistic self-consciousness. Some hints of the techniques Joyce frequently employed in later works, such as stream of consciousness, interior monologue, and references to a character's psychic reality rather than to his external surroundings are evident throughout this novel.[68]

Exiles and poetry

Despite early interest in the theatre, Joyce published only one play, Exiles, begun shortly after the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 and published in 1918. A study of a husband-and-wife relationship, the play looks back to The Dead (the final story in Dubliners) and forward to Ulysses, which Joyce began around the time of the play's composition.

Joyce published a number of books of poetry. His first mature published work was the satirical broadside "The Holy Office" (1904), in which he proclaimed himself to be the superior of many prominent members of the Celtic Revival. His first full-length poetry collection, Chamber Music (1907; referring, Joyce joked, to the sound of urine hitting the side of a chamber pot), consisted of 36 short lyrics. This publication led to his inclusion in the Imagist Anthology, edited by Ezra Pound, who was a champion of Joyce's work. Other poetry Joyce published in his lifetime include "Gas from a Burner" (1912), Pomes Penyeach (1927) and "Ecce Puer" (written in 1932 to mark the birth of his grandson and the recent death of his father). It was published by the Black Sun Press in Collected Poems (1936).

Ulysses

As he was completing work on Dubliners in 1906, Joyce considered adding another story featuring a Jewish advertising canvasser called Leopold Bloom under the title Ulysses. Although he did not pursue the idea further at the time, he eventually commenced work on a novel using both the title and basic premise in 1914. The writing was completed in October 1921. Three more months were devoted to working on the proofs of the book before Joyce halted work shortly before his self-imposed deadline, his 40th birthday (2 February 1922).

Thanks to Ezra Pound, serial publication of the novel in the magazine The Little Review began in March 1918. This magazine was edited by Margaret C. Anderson and Jane Heap, with the intermittent financial backing of John Quinn, a successful New York commercial lawyer with an interest in contemporary experimental art and literature.

This provoked the first accusations of obscenity with which the book would be identified for so long. Its amorphous structure with frank, intimate musings (‘stream of consciousness’) were seen to offend both church and state. The publication encountered problems with New York Postal Authorities; serialisation ground to a halt in December 1920; the editors were convicted of publishing obscenity in February 1921.[69] Although the conviction was based on the "Nausicaä" episode of Ulysses, The Little Review had fuelled the fires of controversy with dada poet Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven's defence of Ulysses in an essay "The Modest Woman."[70] Joyce's novel was not published in the United States until 1934.[71]

Partly because of this controversy, Joyce found it difficult to get a publisher to accept the book, but it was published in 1922 by Sylvia Beach from her well-known Rive Gauche bookshop, Shakespeare and Company. An English edition published the same year by Joyce's patron, Harriet Shaw Weaver, ran into further difficulties with the United States authorities, and 500 copies that were shipped to the States were seized and possibly destroyed. The following year, John Rodker produced a print run of 500 more intended to replace the missing copies, but these were burned by English customs at Folkestone. A further consequence of the novel's ambiguous legal status as a banned book was that "bootleg" versions appeared, including pirate versions from the publisher Samuel Roth. In 1928, a court injunction against Roth was obtained and he ceased publication.

With the appearance of Ulysses, and T.S. Eliot's poem, The Waste Land, 1922 was a key year in the history of English-language literary modernism. In Ulysses, Joyce employs stream of consciousness, parody, jokes, and almost every other literary technique to present his characters.[72] The action of the novel, which takes place in a single day, 16 June 1904, sets the characters and incidents of the Odyssey of Homer in modern Dublin and represents Odysseus (Ulysses), Penelope and Telemachus in the characters of Leopold Bloom, his wife Molly Bloom and Stephen Dedalus, parodically contrasted with their lofty models. The book explores various areas of Dublin life, dwelling on its squalor and monotony. Nevertheless, the book is also an affectionately detailed study of the city, and Joyce claimed that if Dublin were to be destroyed in some catastrophe it could be rebuilt, brick by brick, using his work as a model.[73] In order to achieve this level of accuracy, Joyce used the 1904 edition of Thom's Directory—a work that listed the owners and/or tenants of every residential and commercial property in the city. He also bombarded friends still living there with requests for information and clarification.

The book consists of 18 chapters, each covering roughly one hour of the day, beginning around about 8 a.m. and ending sometime after 2 a.m. the following morning. Each of the 18 chapters of the novel employs its own literary style. Each chapter also refers to a specific episode in Homer's Odyssey and has a specific colour, art or science and bodily organ associated with it. This combination of kaleidoscopic writing with an extreme formal, schematic structure represents one of the book's major contributions to the development of 20th century modernist literature.[74] Other contributions include the use of classical mythology as a framework for his book and the near-obsessive focus on external detail in a book in which much of the significant action is happening inside the minds of the characters. Nevertheless, Joyce complained that, "I may have oversystematised Ulysses," and played down the mythic correspondences by eliminating the chapter titles that had been taken from Homer.[75] Joyce was reluctant to publish the chapter titles because he wanted his work to stand separately from the Greek form. It was only when Stuart Gilbert published his critical work on Ulysses in 1930 that the schema was supplied by Joyce to Gilbert. But as Terrence Killeen points out this schema was developed after the novel had been written and was not something that Joyce consulted as he wrote the novel.[76]

Finnegans Wake

Having completed work on Ulysses, Joyce was so exhausted that he did not write a line of prose for a year.[77] On 10 March 1923 he informed his patron, Harriet Shaw Weaver: "Yesterday I wrote two pages—the first I have since the final Yes of Ulysses. Having found a pen, with some difficulty I copied them out in a large handwriting on a double sheet of foolscap so that I could read them. Il lupo perde il pelo ma non il vizio, the Italians say. 'The wolf may lose his skin but not his vice' or 'the leopard cannot change his spots.'"[78] Thus was born a text that became known, first, as Work in Progress and later Finnegans Wake.

By 1926 Joyce had completed the first two parts of the book. In that year, he met Eugene and Maria Jolas who offered to serialise the book in their magazine transition. For the next few years, Joyce worked rapidly on the new book, but in the 1930s, progress slowed considerably. This was due to a number of factors, including the death of his father in 1931, concern over the mental health of his daughter Lucia, and his own health problems, including failing eyesight. Much of the work was done with the assistance of younger admirers, including Samuel Beckett. For some years, Joyce nursed the eccentric plan of turning over the book to his friend James Stephens to complete, on the grounds that Stephens was born in the same hospital as Joyce exactly one week later, and shared the first name of both Joyce and of Joyce's fictional alter-ego, an example of Joyce's superstitions.[79]

Reaction to the work was mixed, including negative comment from early supporters of Joyce's work, such as Pound and the author's brother, Stanislaus Joyce.[80] To counteract this hostile reception, a book of essays by supporters of the new work, including Beckett, William Carlos Williams and others was organised and published in 1929 under the title Our Exagmination Round His Factification for Incamination of Work in Progress. At his 57th birthday party at the Jolases' home, Joyce revealed the final title of the work and Finnegans Wake was published in book form on 4 May 1939. Later, further negative comments surfaced from doctor and author Hervey Cleckley, who questioned the significance others had placed on the work. In his book The Mask of Sanity, Cleckley refers to Finnegans Wake as "a 628-page collection of erudite gibberish indistinguishable to most people from the familiar word salad produced by hebephrenic patients on the back wards of any state hospital."[81]

Joyce's method of stream of consciousness, literary allusions and free dream associations was pushed to the limit in Finnegans Wake, which abandoned all conventions of plot and character construction and is written in a peculiar and obscure English, based mainly on complex multi-level puns. This approach is similar to, but far more extensive than, that used by Lewis Carroll in Jabberwocky. This has led many readers and critics to apply Joyce's oft-quoted description in the Wake of Ulysses as his "usylessly unreadable Blue Book of Eccles"[82] to the Wake itself. However, readers have been able to reach a consensus about the central cast of characters and general plot.

Much of the wordplay in the book stems from the use of multilingual puns which draw on a wide range of languages. The role played by Beckett and other assistants included collating words from these languages on cards for Joyce to use and, as Joyce's eyesight worsened, of writing the text from the author's dictation.[83]

The view of history propounded in this text is very strongly influenced by Giambattista Vico, and the metaphysics of Giordano Bruno of Nola are important to the interplay of the "characters". Vico propounded a cyclical view of history, in which civilisation rose from chaos, passed through theocratic, aristocratic, and democratic phases, and then lapsed back into chaos. The most obvious example of the influence of Vico's cyclical theory of history is to be found in the opening and closing words of the book. Finnegans Wake opens with the words "riverrun, past Eve and Adam's, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodius vicus of recirculation back to Howth Castle and Environs" ("vicus" is a pun on Vico) and ends "A way a lone a last a loved a long the". In other words, the book ends with the beginning of a sentence and begins with the end of the same sentence, turning the book into one great cycle.[84] Indeed, Joyce said that the ideal reader of the Wake would suffer from "ideal insomnia"[85] and, on completing the book, would turn to page one and start again, and so on in an endless cycle of reading.

Legacy

Joyce's work has been an important influence on writers and scholars such as Samuel Beckett,[86] Seán Ó Ríordáin,[87] Jorge Luis Borges,[88] Flann O'Brien,[89] Salman Rushdie,[90] Robert Anton Wilson,[91] John Updike,[92] David Lodge,[93] Cormac McCarthy,[94] and Joseph Campbell.[95] Ulysses has been called "a demonstration and summation of the entire [Modernist] movement".[96] The Bulgarian-French literary theorist Julia Kristeva characterised Joyce's novel writing as "polyphonic" and a hallmark of postmodernity alongside the poets Mallarmé and Rimbaud.[97]

Some scholars, notably Vladimir Nabokov, have reservations, often championing some of his fiction while condemning other works. In Nabokov's opinion, Ulysses was brilliant,[98] while Finnegans Wake was horrible.[99]

Joyce's influence is also evident in fields other than literature. The sentence "Three quarks for Muster Mark!" in Joyce's Finnegans Wake[100] is the source of the word "quark", the name of one of the elementary particles proposed by the physicist Murray Gell-Mann in 1963.[101]

The work and life of Joyce is celebrated annually on 16 June, known as Bloomsday, in Dublin and in an increasing number of cities worldwide, and critical studies in scholarly publications, such as the James Joyce Quarterly, continue. Both popular and academic uses of Joyce's work were hampered by restrictions imposed by Stephen J. Joyce, Joyce's grandson, and executor of his literary estate until his 2020 death.[102][103] On 1 January 2012, those restrictions were lessened by the expiry of copyright protection of much of the published work of James Joyce.[104][105]

In April 2013 the Central Bank of Ireland issued a silver €10 commemorative coin in honour of Joyce that misquoted a famous line from Ulysses.[106]

Bibliography

Prose

- Dubliners (short-story collection, 1914)

- A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (novel, 1916)

- Ulysses (novel, 1922)

- Finnegans Wake (1939, restored 2012)

Poetry collections

- Chamber Music (poems, Elkin Mathews, 1907)

- Giacomo Joyce (written 1907, published by Faber and Faber, 1968)

- Pomes Penyeach (poems, Shakespeare and Company, 1927)

- Collected Poems (poems, Black Sun Press, 1936, which includes Chamber Music, Pomes Penyeach and other previously published works)

Play

- Exiles (play, 1918)

Posthumous publications and drafts

Fiction

- Stephen Hero (precursor to A Portrait; written 1904–06, published 1944)

- The Cat and the Devil (London: Faber and Faber, 1965)

- The Cats of Copenhagen (Ithys Press, 2012)

- Finn's Hotel (Ithys Press, 2013)

Non-Fiction

- The Critical Writings of James Joyce (Eds. Ellsworth Mason and Richard Ellmann, 1959)

- Letters of James Joyce Vol. 1 (Ed. Stuart Gilbert, 1957)

- Letters of James Joyce Vol. 2 (Ed. Richard Ellmann, 1966)

- Letters of James Joyce Vol. 3 (Ed. Richard Ellmann, 1966)

- Selected Letters of James Joyce (Ed. Richard Ellmann, 1975)

Notes and references

- The second name was mistakenly registered as "Augusta". Joyce was named and baptised James Augustine Joyce, for his paternal grandfather, Costello (1992) p. 53, and the Birth and Baptismal Certificate re-issued in 2004 and reproduced above in this article shows "Augustine". Ellman says: "The second child, James Augusta (as the birth was incorrectly registered) ...". Ellmann (1982) p. 21.

- Ellman, p. 505, citing Power, From an Old Waterford House (London, n.d.), pp. 63–64

- Bol, Rosita. "What does Joyce mean to you?". The Irish Times. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- Jackson, John Wyse; Costello, Peter (July 1998). "John Stanislaus Joyce: the voluminous life and genius of James Joyce's father"

- Jackson, John Wyse; Costello, Peter (July 1998). "John Stanislaus Joyce: the voluminous life and genius of James Joyce's father" (book excerpt). excerpt appearing in The New York Times. New York: St. Martin's Press. ch.1 "Ancestral Joyces". ISBN 978-0-312-18599-2. OCLC 38354272. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

To find the missing link in the chain it is necessary to turn south to County Kerry. Some time about 1680, William FitzMaurice, 19th of the Lords of Kerry ... required a new steward for the household at his family seat at Lixnaw on the Brick river, a few miles south-west of Listowel in the Barony of Clanmaurice in North Kerry. He found Seán Mór Seoighe (Big John Joyce) ... Seán Mór Seoige came from Connemara, most likely from in or near the Irish-speaking Joyce Country itself, in that wild area south of Westport, County Mayo.

- "'Why are you so afraid of thunder?' asked [Arthur] Power, 'your children don't mind it.' 'Ah,' said Joyce contemptuously, 'they have no religion.' Joyce's fears were part of his identity, and he had no wish, even if he had had the power, to slough any of them off." Ellmann (1982), p. 514, citing Power, From an Old Waterford House (London, n.d.), p. 71

- In Search of Ireland's Heroes: Carmel McCaffrey pp. 279–86

- Ellmann (1982), pp. 32–34.

- James Joyce: Richard Ellmann 1982 pp. 54–55

- Themodernworld.com Archived 22 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Ellmann (1982), pp. 60, 190, 340, 342; Cf. Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Wordsworth 1992, Intro. & Notes J. Belanger, 2001, 136, n. 309: "Synopsis Philosophiae ad mentem D. Thomae. This appears to be a reference to Elementa Philosophiae ad mentem D. Thomae, a selection of Thomas Aquinas's writings edited and published by G.M. Mancini, Professor of Theology at the Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas, Angelicum in Rome (see The Irish Ecclesiastical Record, Vol V, Year 32, No. 378, June 1899, p. 570

- Jordan, Anthony, "An Irishman's Diary", Irish Times, 20 February 2012

- Arthur Griffith with James Joyce & WB Yeats – Liberating Ireland by Anthony J. Jordan p. 53. Westport Books 2013. ISBN 978-0-9576229-0-6

- "Residents of a house 8.1 in Royal Terrace (Clontarf West, Dublin)". National Archives of Ireland. 1901. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- Richard Ellmann: James Joyce (1959) pp. 117–18

- She was originally diagnosed with cirrhosis of the liver, but this proved incorrect, and she was diagnosed with cancer in April 1903. Ellmann (1982), pp. 128–29

- Ellmann (1982), pp. 129, 136

- "History of the Feis Ceoil Association". Archived from the original on 1 April 2007. Retrieved 9 November 2009.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link). Siemens Feis Ceoil Association. 1 April 2007 version retrieved from the Internet archive on 9 November 2009.

- Michael Parsons. "Michael Flatley confirms he owns medal won by James Joyce". Irishtimes.com. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- "Joyce – Other works". The James Joyce Centre. Archived from the original on 24 June 2010. Retrieved 22 February 2010.

- Menand, Louis (2 July 2012). "Silence, exile, punning". The New Yorker.

They walked to Ringsend, on the south bank of the Liffey, where (and here we can drop the Dante analogy) she put her hand inside his trousers and masturbated him. It was June 16, 1904, the day on which Joyce set “Ulysses.” When people celebrate Bloomsday, that is what they are celebrating.

- "On this day...30 September". The James Joyce Centre.

- Ellmann (1982), pp. 161–62.

- Ellmann (1982), p. 230.

- Ellmann, p. 175.

- McCourt 2001.

- Hawley, M., "James Joyce in Trieste", Radio Netherlands Worldwide, 1 January 2000.

- According to Ellmann, Stanislaus allowed Joyce to collect his pay, "to simplify matters" (p. 213).

- The worst of the conflicts were during July 1910 (Ellmann (1982), pp. 311–13).

- Williams, Bob. Joycean Chronology. Archived 22 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine The Modern World, 6 November 2002, Retrieved on 9 November 2009.

- Beja, Morris (1992). James Joyce: A Literary Life. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio State University Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-8142-0599-0.

- Ellmann (1982), pp. 300–03, 308, 311.

- Ellmann (1982), pp. 384–85.

- Ellmann (1982), p. 272.

- Ellmann (1982), pp. 268, 417.

- Ellman (1982), p. 386.

- Sultan, Stanley (1987). Eliot, Joyce, and Company. Oxford University Press. pp. 208–209.

- Segall, Jeffrey (1993). Joyce in America: Cultural Politics and the Trials of Ulysses. University of California Press. pp. 5–6.

- Fairhall, James (1995). James Joyce and the Question of History. Cambridge University Press. pp. 51–55.

- McCourt, John (2009). James Joyce in Context. Cambridge University Press. pp. 287–290.

- Franz Karl Stanzel: James Joyce in Kakanien (1904–1915). Würzburg 2019, ISBN 978-3-8260-6615-3, p 29.

- Ellmann (1982) pp. 566–74.

- Shloss, p. 278.

- Pepper, Tara

- Shloss p. 297.

- The literary executor of the Joyce estate, Stephen J. Joyce, burned letters written by Lucia that he received upon Lucia's death in 1982.(Stanley, Alessandra. "Poet Told All; Therapist Provides the Record," The New York Times, 15 July 1991. Retrieved 9 July 2007). Stephen Joyce stated in a letter to the editor of The New York Times that "Regarding the destroyed correspondence, these were all personal letters from Lucia to us. They were written many years after both Nonno and Nonna [i.e. Mr and Mrs Joyce] died and did not refer to them. Also destroyed were some postcards and one telegram from Samuel Beckett to Lucia. This was done at Sam's written request."Joyce, Stephen (31 December 1989). "The Private Lives of Writers" (Letter to the Editor). The New York Times. Retrieved 9 November 2009.

- Platt, Len (2011). James Joyce: Texts and Contexts. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 131.

- Letter to Nora Barnacle, August 29, 1904, in R. Ellmann, ed., Selected Letters of James Joyce (London: Faber and Faber, 1975), pp. 25–26. ISBN 0-571-09306-X

- Mierlo, C. Van, James Joyce and Catholicism: The Apostate's Wake (London & New York: Bloombury, 2017), p. 3.

- Ellmann (1982), p. 742, citing a 1953 interview with George ("Giorgio") Joyce.

- Segall, Jeffrey Joyce in America: cultural politics and the trials of Ulysses, p. 140, University of California Press 1993

- Segall, Jeffrey Joyce in America: cultural politics and the trials of Ulysses, p. 142, University of California Press 1993

- Segall, Jeffrey Joyce in America: cultural politics and the trials of Ulysses, p. 160, University of California Press 1993

- Davison, Neil R., James Joyce, Ulysses, and the Construction of Jewish Identity: Culture, Biography, and 'the Jew' in Modernist Europe, p. 78, Cambridge University Press, 1998

- Hughs, Eamonn in Robert Welch's Irish writers and religion, pp. 116–37, Rowman & Littlefield 1992

- R.J. Schork, "James Joyce and the Eastern Orthodox Church" in Journal of Modern Greek Studies, vol. 17, 1999

- Free translation from: Eco, Umberto. Las poéticas de Joyce. Barcelona: DeBolsillo, 2011. ISBN 978-84-9989-253-5, p. 17

- Gibson, Andrew, James Joyce, p. 41, Reaktion Books 2006

- "James Joyce and the Jesuits: a sort of homecoming". Catholicireland.net. 30 November 1999. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- Ellmann (1982), pp. 740-41

- Ellmann (1982), p. 743

- Jordan, Anthony J. (13 January 2018). "Remembering James Joyce 77 Years to the Day after his Death". The Irish Times. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- Irish Times, 14 October 2019

- Irish Times Comment, 26 October 2019

- Osteen, Mark (22 June 1995). "A Splendid Bazaar: The Shopper's Guide to the New Dubliners". Studies in Short Fiction.

- Michael Groden. "Notes on James Joyce's Ulysses". The University of Western Ontario. Archived from the original on 1 November 2005.

- MacBride, p. 14.

- Deming, p. 749.

- Obscenity trial of Ulysses in The Little Review; Gillers, pp. 251–62.

- Gammel, Irene. Baroness Elsa: Gender, Dada and Everyday Modernity. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002, 253.

- The fear of prosecution for publication ended after the court decision of United States v. One Book Called Ulysses, 5 F.Supp. 182 (S.D.N.Y. 1933). Ellman, pp. 666–67.

- Examined at length in Vladimir Nabokov's Lectures on Ulysses. A Facsimile of the Manuscript. Bloomfield Hills/Columbia: Bruccoli Clark, 1980.

- Adams, David. Colonial Odysseys: Empire and Epic in the Modernist Novel. Cornell University Press, 2003, p. 84.

- Sherry, Vincent B. James Joyce: Ulysses. Cambridge University Press, 2004, p. 102.

- Dettmar, Kevin J.H. Rereading the New: A Backward Glance at Modernism. University of Michigan Press, 1992, p. 285.

- Ulysses Unbound: Terence Killeen

- Bulson, Eric. The Cambridge Introduction to James Joyce. Cambridge University Press, 2006, p. 14.

- Joyce, James. Ulysses: The 1922 Text. Oxford University Press, 1998, p. xlvii.

- Ellmann (1982), pp. 591–92.

- Ellmann (1982), pp. 577–85.

- Cleckley, Hervey (1982). The Mask of Sanity. Revised Edition. Mosby Medical Library. ISBN 0-452-25341-1.

- Finnegans Wake, 179. 26–27.

- Gluck, p. 27.

- Shockley, Alan (2009). "Playing the Square Circle: Musical Form and Polyphony in the Wake". In Friedman, Alan W.; Rossman, Charles (eds.). De-Familiarizing Readings: Essays from the Austin Joyce Conference. European Joyce Studies. 18. Amsterdam: Editions Rodopi. p. 104. ISBN 978-90-420-2570-7.

- Finnegans Wake, 120. 9–16.

- Friedman, Melvin J. A review Archived 27 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine of Barbara Reich Gluck's Beckett and Joyce: friendship and fiction, Bucknell University Press (June 1979), ISBN 0-8387-2060-9. Retrieved 3 December 2006.

- Sewell, Frank (2000). Modern Irish Poetry: A New Alhambra (PDF). Oxford University Press. pp. Introduction p. 3. ISBN 978-0-19-818737-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- Williamson, pp. 123–24, 179, 218.

- For example, Hopper, p. 75, says "In all of O'Brien's work the figure of Joyce hovers on the horizon ...".

- Interview of Salman Rushdie, by Margot Dijkgraaf for the Dutch newspaper NRC Handelsblad, translated by K. Gwan Go. Retrieved 3 December 2006.

- Edited transcript of a 23 April 1988 interview of Robert Anton Wilson Archived 31 March 2006 at the Wayback Machine by David A. Banton, broadcast on HFJC, 89.7 FM, Los Altos Hills, California. Retrieved 3 December 2006.

- Updike has referred to Joyce as influential in a number of interviews and essays. The most recent of such references is in the foreword to The Early Stories: 1953–1975 (London: Hamish Hamilton, 2003), p. x. John Collier wrote favorably of "that city of modern prose," and added, "I was struck by the great number of magnificent passages in which words are used as they are used in poetry, and in which the emotion which is originally Other instances include an interview with Frank Gado in First Person: Conversations with Writers and their Writing (Schenectady, NY: Union College Press, 1973), p. 92, and James Plath's Conversations with John Updike (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 1994), pp. 197, 223.

- Guignery, Vanessa; François Gallix (2007). Pre and Post-publication Itineraries of the Contemporary Novel in English. Publibook. p. 126. ISBN 978-2-7483-3510-1. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- Jones, Josh (13 August 2013). "Cormac McCarthy's Three Punctuation Rules and How They All Go Back to James Joyce". Open Culture. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- "About Joseph Campbell". Archived from the original on 1 January 2007. Retrieved 10 December 2006.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link), Joseph Campbell Foundation. 1 January 2007 version retrieved from the Internet archive on 9 November 2009.

- Beebe, p. 176.

- Julia Kristéva, La Révolution du langage poétique, Paris, Seuil, 1974.

- "When I want good reading I reread Proust's A la Recherche du Temps Perdu or Joyce's Ulysses" (Nabokov, letter to Elena Sikorski, 3 August 1950, in Nabokov's Butterflies: Unpublished and Uncollected Writings [Boston: Beacon, 2000], pp. 464–65). Nabokov put Ulysses at the head of his list of the "greatest twentieth century masterpieces" (Nabokov, Strong Opinions [New York: McGraw-Hill, 1974] excerpt).

- "Of course, it would have been unseemly for a monarch to appear in the robes of learning at a university lectern and present to rosy youths Finnigan's Wake [sic] as a monstrous extension of Angus MacDiarmid's "incoherent transactions" and of Southey's Lingo-Grande ..." (Nabokov, Pale Fire [New York: Random House, 1962], p. 76). The comparison is made by an unreliable narrator, but Nabokov in an unpublished note had compared "the worst parts of James Joyce" to McDiarmid and to Swift's letters to Stella (quoted by Brian Boyd, "Notes" in Nabokov's Novels 1955–1962: Lolita / Pnin / Pale Fire [New York: Library of America, 1996], 893).

- Three quarks for Muster Mark! Archived 8 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Text of Finnegans Wake at Trent University, Peterborough, Ontario. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- "quark". Archived from the original on 2 July 2007. Retrieved 28 November 2006.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link), American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition 2000. 2 July 2007 version retrieved from the Internet archive on 9 November 2009.

- Max, D.T. (19 June 2006). "The Injustice Collector". The New Yorker.

- Roberts, S., "Stephen Joyce Dies at 87; Guarded Grandfather’s Literary Legacy", The New York Times, February 7, 2020.

- Kileen, Terence (16 June 2011). "Joyce enters the public domain". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- Kileen, Terence (31 December 2011). "EU copyright on Joyce works ends at midnight". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 3 January 2012. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- "Error in Ulysses line on special €10 coin issued by Central Bank". RTÉ News. 10 April 2013.

Additional references

- Beebe, Maurice (Fall 1972). "Ulysses and the Age of Modernism". James Joyce Quarterly (University of Tulsa) 10 (1): 172–88

- Beja, Morris. James Joyce: A Literary Life. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1992. ISBN 0-8142-0599-2.

- Borges, Jorge Luis, (ed.) Eliot Weinberger, Borges: Selected Non-Fictions, Penguin (31 October 2000). ISBN 0-14-029011-7.

- Bulson, Eric. The Cambridge Introduction to James Joyce. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0-521-84037-8.

- Cavanaugh, Tim, "Ulysses Unbound: Why does a book so bad it "defecates on your bed" still have so many admirers?", reason, July 2004.

- Costello, Peter. James Joyce: the years of growth, 1892–1915. New York: Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, 1992. ISBN 0-679-42201-3.

- Deming, Robert H. James Joyce: The Critical Heritage. Routledge, 1997.

- Ellmann, Richard, James Joyce. Oxford University Press, 1959, revised edition 1982. ISBN 0-19-503103-2.

- Gammel, Irene. Baroness Elsa: Gender, Dada and Everyday Modernity. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002, 253.

- Gillers, Stephen (2007). "A Tendency to Deprave and Corrupt: The Transformation of American Obscenity Law from Hicklin to Ulysses". Washington University Law Review. 85 (2): 215–96. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- Gluck, Barbara Reich. Beckett and Joyce: Friendship and Fiction. Bucknell University Press, 1979.

- Goldman, Jonathan, ed. Joyce and the Law. University Press of Florida (2017). ISBN 978-0813054742.

- Hopper, Keith, Flann O'Brien: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Post-Modernist, Cork University Press (1995). ISBN 1-85918-042-6.

- Jordan, Anthony J, Arthur Griffith with James Joyce & WB Yeats – Liberating Ireland, [Westport Books] (2013) ISBN 978-0-9576229-0-6.

- Jordan, Anthony J, James Joyce Unplugged Westport Books 2017 ISBN 978-0-9576229-2-0

- Joyce, Stanislaus, My Brother's Keeper, New York: Viking Press, 1969.

- MacBride, Margaret. Ulysses and the Metamorphosis of Stephen Dedalus. Bucknell University Press, 2001.

- McCourt, John, The Years of Bloom: James Joyce in Trieste, 1904–1920, The Lilliput Press, 2001. ISBN 1-901866-71-8.

- McCourt, John, ed. James Joyce in Context. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-521-88662-8.

- Pepper, Tara. "Portrait of the Daughter: Two works seek to reclaim the legacy of Lucia Joyce." Newsweek International . 8 March 2003.

- Shloss, Carol Loeb. Lucia Joyce: To Dance in the Wake. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2004. ISBN 0-374-19424-6.

- Williamson, Edwin, Borges: A Life, Viking Adult 2004. ISBN 0-670-88579-7.

Further reading

- Bowker, Gordon (2011). James Joyce : a biography. Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Burgess, Anthony, Here Comes Everybody: An Introduction to James Joyce for the Ordinary Reader, Faber & Faber (1965). (Published in America as Re Joyce, Hamlyn Paperbacks Rev. ed edition (1982)). ISBN 0-600-20673-4.

- Burgess, Anthony, Joysprick: An Introduction to the Language of James Joyce (1973), Harcourt (1975). ISBN 0-15-646561-2.

- Clark, Hilary, The Fictional Encyclopaedia: Joyce, Pound, Sollers. Routledge Revivals, 2011. ISBN 978-0-415-66833-0

- Dening, Greg (2007–2008). "James Joyce and the soul of Irish Jesuitry". Australasian Journal of Irish Studies. 7: 10–19.

- Everdell, William R., The First Moderns: Profiles in the Origins of Twentieth-Century Thought. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997. ISBN 0-226-22480-5 (cloth) ISBN 0-226-22481-3 (bpk)

- Fargnoli, A. Nicholas, and Michael Patrick Gillespie, Eds. Critical Companion to James Joyce: A Literary Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 2014. ISBN 0-8160-6232-3.

- Fennell, Conor. A Little Circle of Kindred Minds: Joyce in Paris. Green Lamp Editions, 2011.

- Levin, Harry (ed. with introduction and notes). The Essential James Joyce. Cape, 1948. Revised edition Penguin in association with Jonathan Cape, 1963.

- Jordan, Anthony J. James Joyce Unplugged. Westport Books, 2017.

- Jordan, Anthony J, 'Arthur Griffith with James Joyce & WB Yeats. Liberating Ireland'. Westport Books 2013.

- Levin, Harry, James Joyce. Norfolk, CT: New Directions, 1941 (1960).

- Quillian, William H. Hamlet and the new poetic: James Joyce and T.S. Eliot. Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press, 1983.

- Read, Forrest. Pound/Joyce: The Letters of Ezra Pound to James Joyce, with Pound's Essays on Joyce. New Directions, 1967.

- Special issue on James Joyce, In-between: Essays & Studies in Literary Criticism, Vol. 12, 2003. [Articles]

- Irish Writers on Writing featuring James Joyce. Edited by Eavan Boland (Trinity University Press, 2007).

- A Bash in the Tunnel. James Joyce by the Irish. 1 November 1970. by John Ryan (Editor)

- Gerhard Charles Rump, Schmidt, Joce und die Suprasegmentalien, in: Interaktionsanalysen. Aspekte dialogischer Kommunikation. Gerhard Charles Rump and Wilfried Heindrichs (eds), Hildesheim 1982, pp. 222-238

External links

Joyce Papers, National Library of Ireland

- The Joyce Papers 2002, c. 1903–1928

- The James Joyce – Paul Léon Papers, 1930–1940

- Hans E. Jahnke Bequest at the Zurich James Joyce Foundation online at the National Library Of Ireland, 2014

- James Joyce by Djuna Barnes: Vanity Fair, March, 1922

Electronic editions

- Works by James Joyce at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by James Joyce at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by James Joyce at Project Gutenberg

Resources

- "Archival material relating to James Joyce". UK National Archives.

- The James Joyce Scholars' Collection from the University of Wisconsin Digital Collections Center

- James Joyce from Dublin to Ithaca Exhibition from the collections of Cornell University

- Bibliography of Joycean Scholarship, Articles and Literary Criticism