HMS Phoenix (1759)

HMS Phoenix was a 44-gun[1][2] fifth-rate ship of the Royal Navy. She was launched in 1759 and sunk in 1780 and saw service during the American War of Independence.

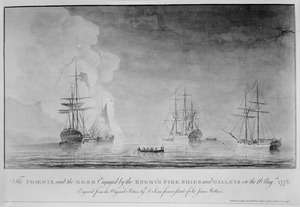

The engraving The Phoenix and the Rose engaged by the enemy's fire ships and galleys on the 16 Aug. 1776. by Dominic Serres after a sketch by Sir James Wallace | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | HMS Phoenix |

| Ordered: | 5 January 1758 |

| Builder: | John & Robert Batson, Limehouse |

| Laid down: | February 1758 |

| Launched: | 25 June 1759 |

| Completed: | By 26 July 1759 |

| Fate: | Wrecked 4 October 1780 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | 40-gun fifth-rate frigate |

| Tons burthen: | 84267⁄94 bm |

| Length: | |

| Beam: | 36 ft 9.75 in (11.2205 m) |

| Depth of hold: | 15 ft 11.5 in (4.864 m) |

| Sail plan: | Full rigged ship |

| Complement: | 280 |

| Armament: |

|

Launch

Phoenix was launched in 1759 under Captain Prince Edward, Duke of York and Albany[3]

Activities in North America

Naval operations

Phoenix saw service during the American War of Independence under Captain Hyde Parker, Jr.[2] The ship was assigned to New York and by 5 June 1776 was laying off Sandy Hook, New Jersey with a small flotilla of ships.[4] Later that month, Phoenix captured at least three ships and disrupted an American attack on a lighthouse near Sandy Hook.[4] In the early days of July 1776, Phoenix, along with Rose and Greyhound moved toward Red Hook, Brooklyn and anchored at Gravesend, Brooklyn.[4] On 8 July 1776, Parker was ordered to assume command of HMS Rose and move upriver from New York City.

She, along with HMS Rose and three smaller ships, launched an attack on New York City on 12 July 1776.[1] During that attack, Phoenix and the other ships easily passed patriot defenses and bombarded urban New York for two hours.[5] This action largely confirmed Continental fears that the Royal Navy could act with relative impunity when attacking deep-water ports.[5] Phoenix continued to harass patriot positions along the Hudson River till 16 August when she withdrew back to the waters off of Staten Island.[6][4] Maps from that autumn show Phoenix and Rose again in the waters south of Manhattan.[7]

Counterfeiting

Phoenix was also involved in a kind of currency war. During the Revolutionary War, the Continental Congress authorized the printing of paper currency called continental currency. As early as January 1776, John and George Folliott began counterfeiting Continental $30 bills on Phoenix.[8] The counterfeiting operation on Phoenix ran till at least April 1777.[9] The counterfeit notes could be purchased for the price of the paper they were printed on.[9] Inflation was indeed a major problem for the rebelling colonists, reaching monthly levels of 47 percent by November 1779.[10] And the Phoenix counterfeiting contributed, at least in part, to such staggering currency problems.[11]

Loss

Phoenix, under Captain Hyde Parker, sunk on the night of 4 October 1780.[12][13] The loss occurred during a major hurricane that disabled England's entire fleet in the West Indies.[13] The loss was memorably recorded by Lieutenant Archer in a letter of 6 November 1780:

If I were to write forever, I could not give you an idea of it; the sea of fire, running as it were the Alps or Peaks of Teneriffe; the wind roaring louder than thunder, the whole made more terrible, if possible, by a very uncommon kind of blue lightning; the poor ship very much pressed, yet doing what she could, shaking her sides and groaning at every stroke.[14]

Before she sunk, the crew cut the mainmast away after the storm felled it.[14]

Over the course of three days, the crew was able to land provisions and stores on the shore of Cuba, a hostile territory then a possession of Spain.[14] Hyde Parker ordered his crew to repaired the damaged cutter and then dispatched it toward Montego Bay in Jamaica.[14] A rescue mission of three fishing boats and, later, the sloop Porcupine evacuated the survivors.[14] Phoenix had lost 20 men when the mainmast fell. The surviving 240 men reached Montego Bay safely on 15 October.[15]

Citations and references

Citations

- Chernow, Ron (2011). Washington: A Life. Penguin Books. p. 238. ISBN 978-0143119968.

- Naval Documents of The American Revolution Vol. 5 Part 5 (PDF). U.S. Government Printing Office. 1970. p. 1043.

- Haydn, Joseph (1851). Book of Dignities; containing Rolls of the Official Personages of the British Empire. London: Longman, Brown, Greene, and Longmans. p. 285.

- Morgan, William (1970). Naval Documents of the American Revolution: Volume 5 (PDF). Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. pp. 212–213, 228, 383, 665, 895.

- Fischer, David (2004). Washington's Crossing. Oxford. pp. 83–84. ISBN 9780195181593.

- Hannings, Bud (2008). Chronology of the American Revolution : military and political actions day by day. McFarland & Co. pp. 122, 124. ISBN 9780786429486.

- Digital Collections, The New York Public Library. "(cartographic) A plan of New York Island, with part of Long Island, Staten Island & east New Jersey : with a particular description of the engagement on the woody heights of Long Island, between Flatbush and Brooklyn, on the 27th of August 1776 between His Majesty's forces commanded by General Howe and the Americans under Major General Putnam, shewing also the landing of the British Army on New-York Island, and the taking of the city of New-York &c. on the 15th of September following, with the subsequent disposition of both the armies, (1776-10-19)". The New York Public Library, Astor, Lennox, and Tilden Foundation. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- Newman, E.P. (1958). "The successful British counterfeiting of American paper money during the American Revolution" (PDF). British Numismatic Journal. 29: 179. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- Rhodes, Karl (2012). "The Counterfeiting Weapon" (PDF). Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Region Focus. 16 (1): 34. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- Hanke, Steve. "The Printing Press". Forbes.com. Forbes. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- The counterfeiting of U.S. currency abroad : hearing before the Subcommittee on General Oversight and Investigations of the Committee on Banking and Financial Services, House of Representatives, One Hundred Fourth Congress, second session, February 27, 1996. Washington: U.S. G.P.O. 1996. pp. 6–7. ISBN 0160535395.

- "The Shipwreck of the Phoenix at Night on the Coast of Cuba, 4 October 1780 926827". National Trust Collections. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- Bentley, Richard (16 January 1907). "Weather in War-Time". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society. 33 (142): 136.

- Paine, Ralph (1921). Lost Ships and Lonely Seas. New York: The Century Co. pp. 212–231.

sea-room.

- Clarke, James Stanier; McArthur, John, eds. (2010) [First published 1801]. The Naval Chronicle: Containing a General and Biographical History of the Royal Navy of the United Kingdom with a Variety of Original Papers on Nautical Subjects. Volume 5. p. 293. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511731570. ISBN 9780511731570. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

References

- Hepper, David J. (1994) British Warship Losses in the Age of Sail, 1650–1859. (Rotherfield: Jean Boudriot). ISBN 0-948864-30-3