History of Hong Kong

The region of Hong Kong has been inhabited since the Old Stone Age, later becoming part of the Chinese empire with its loose incorporation into the Qin dynasty (221–206 BC). Starting out as a farming fishing village and salt production site, it became an important free port and eventually a major international financial centre.[1]

| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of Hong Kong |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

| By topic |

|

The Qing dynasty ceded Hong Kong to the British Empire in 1842 through the treaty of Nanjing, ending the First Opium War. Hong Kong then became a British crown colony.[2] Britain also won the Second Opium War, forcing the Qing Empire to cede Kowloon in 1860, while leasing the New Territories for 99 years from 1898.[3][4]

Japan occupied Hong Kong from 1941 to 1945 during the Second World War.[5] By the end of the war in 1945, Hong Kong had been liberated by joint British and Chinese troops and returned to British rule.[6] Hong Kong greatly increased its population from refugees from Mainland China, particularly during the Korea War and the Great Leap Forward. In the 1950s, Hong Kong transformed from a territory of entrepôt trade to one of industry and manufacturing.[7] The Chinese economic reform prompted manufacturers to relocate to China, leading Hong Kong to develop its commercial and financial industry.

In 1984, the British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher signed the Sino-British Joint Declaration, which incited a wave of emigration from Hong Kong.[8] The Handover of Hong Kong on July 1, 1997, returned Hong Kong to Chinese rule, and it adopted the Hong Kong Basic Law.[9][10]

In the 21st century, Hong Kong has continued to enjoy success as a financial center. However, civil unrest, dissatisfaction with the government and Chinese influence, in general, has been a central issue.[11] The planned implementation of Hong Kong Basic Law Article 23 caused great controversy and a massive demonstration on 1 July 2003, causing the bill to be shelved.[12] Citizens expressed displeasure at their electoral system, culminating in the 2014 Hong Kong protests.[13] In 2019, the proposed Hong Kong extradition bill was seen as another step taken by the Chinese Communist Party to undermine the law and human rights in Hong Kong, instigating multiple protests.[14] In 2020, the National People's Congress passed a national security law that was highly scrutinzed by the pro-democracy faction; it was a catalyst that provoked many protests throughout the island.[15][16]

Prehistoric era

Archaeological findings suggesting human activity in Hong Kong date back over 30,000 years. Stone tools from the Old Stone Age have been excavated in Sai Kung in Wong Tei Tung.[17] The stone tools found in Sai Kung were perhaps from a stone tool making ground from perhaps the Late Neolithic Period or Early Bronze Age.[18]

Evidence of an Upper Paleolithic settlement in Hong Kong was found at Wong Tei Tung in Sham Chung beside the Three Fathoms Cove in Sai Kung Peninsula. There were 6000 artefacts found in a slope in the area and jointly confirmed by the Hong Kong Archaeological Society and Centre for Lingnan Archaeology of Zhongshan University.[19]

The Neolithic Era began approximately 7,000 years ago in Hong Kong. The settlers in this area during that time were the Che people, who also settled on the coast of Southern China. Excavations were mostly found on the western shores of Hong Kong. This location was most likely chosen to avoid strong winds from the southeast and to collect food from the nearby shores. Settlement can be found in Cheung Chau, Lantau Island and Lamma Island.

The coming of the Warring States period brought an influx of Yuet people from the north into the area. They probably might have avoided the instabilities at the north and went south. Bronze fishing, combat, and ritual tools were excavated on Lantau Island and Lamma Island. Ma Wan was the earliest settlement with direct evidence in Hong Kong. The Yuet people competed and assimilated with the indigenous Che people.[20] Hong Kong's prehistoric period ended roughly around the duration of the Qin and Han dynasties, when the territory became part of Panyu County.

Imperial China era (221 BC – 1911 AD)

The territory that now comprises Hong Kong was loosely part of China during the Qin dynasty (221–206 BC), and the area was part of the ancient kingdom of Nam Viet (203–111 BC).[21] During the Qin dynasty, the territory was governed by Panyu County until the time of the Jin dynasty.[22]

Archaeological evidence indicates that the population increased during the Han dynasty (206 BC – AD 220). In the 1950s, the tomb at Lei Cheng Uk from the Eastern Han dynasty (25–220 AD) was excavated and archaeologists began to investigate the possibility that salt production flourished in Hong Kong around 2000 years ago, although conclusive evidence has not been found. Tai Po Hoi, the sea of Tai Po, was a major pearl hunting harbour in China from the Han dynasty through to the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), with activities peaking during the Southern Han (917–971).

During the Jin dynasty until the early Tang dynasty, Hong Kong was governed by Bao'an County. Under the Tang dynasty, the Guangdong region flourished as an international trading centre. The Tuen Mun region in what is now Hong Kong's New Territories served as a port, naval base, salt production centre and later as a base for the exploitation of pearls. Lantau Island was also a salt production centre, where riots by salt smugglers against the government broke out. From the middle of the Tang dynasty until the Ming dynasty, Hong Kong was governed by Dongguan County.

On 10 May 1278, Child Zhao Bing, the last Song Dynasty emperor, was enthroned at Mui Wo on Lantau Island; this event is commemorated by the Sung Wong Toi memorial in Kowloon.[23][24] After his defeat at the Battle of Yamen on 19 March 1279, the child emperor committed suicide by drowning with his officials at Mount Ya (modern Yamen Town in Guangdong). Tung Chung valley, named after a hero who gave up his life for the emperor, is believed to have been one of the locations for his court. Hau Wong, an official of the emperor, is still worshipped in Hong Kong today.

During the Mongol period, Hong Kong saw its first population boom as Chinese refugees entered the area. Many refugees were driven by war and famine. Others arrived seeking employment. The five clans of Hau, Tang, Pang and Liu and Man were Chinese from Guangdong, Fujian and Jiangxi who lived mostly in the New Territories and eventually became Punti speakers.

Despite the immigration and sparse development of agriculture, the area was hilly and relatively barren. People had to rely on salt, pearl and fishery trades to produce income. Some clans built walled villages to protect themselves from the threat of bandits, rival clans and wild animals. The Qing-dynasty Chinese pirate Cheung Po Tsai became a legend in Hong Kong. During the Ming dynasty, Hong Kong was administered by Xin'an County.

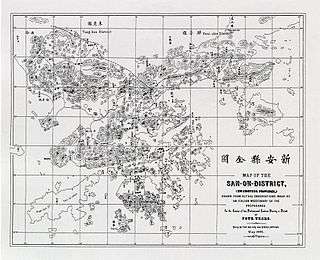

During the Qing dynasty, Hong Kong remained under the governance of Xin'an County, before it was colonised by the British. As a military outpost and trading port, Hong Kong's territory gained the attention of the world. After the Great Clearance policy, ordered by the Kangxi Emperor, many Hakka people migrated from inland China to Xin'an County, which included modern Hong Kong.

Before the British government colonised the New Territories and New Kowloon in 1898, Punti, Hakka, Tanka and Hokkien people had migrated to and stayed in Hong Kong for many years. They are the indigenous inhabitants of Hong Kong. The Punti and Hokkien lived in the New Territories while the Tanka and Hakka lived both in the New Territories and Hong Kong Island. British reports on Hong Kong described the Tanka and Hoklo living in Hong Kong "since time unknown".[25][26] The Encyclopaedia Americana described Hoklo and Tanka as living in Hong Kong "since prehistoric times".[27][28][29]

When the Union Flag was raised over Possession Point on 26 January 1841, the population of Hong Kong island was about 7,450, mostly Tanka fishermen and Hakka charcoal burners living in a number of coastal villages.[30][31] In the 1850s large numbers of Chinese would emigrate from China to Hong Kong due to the Taiping Rebellion. Other events such as floods, typhoons and famine in mainland China would also play a role in establishing Hong Kong as a place to escape the mayhem.

Colonial Hong Kong era (1800s – 1930s)

| Date | Treaty | Outcome | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 January 1841 | Convention of Chuenpi | Preliminary cession of Hong Kong Island to the United Kingdom | Included Green Island and Ap Lei Chau. Before the cession of Hong Kong Island, this territory was governed by Xin'an County . |

| 29 August 1842 | Treaty of Nanking | Cession of Hong Kong Island, founded as a crown colony of the United Kingdom | |

| 18 October 1860 | Convention of Beijing | Cession of Kowloon | South of Boundary Street, including Ngong Shuen Chau. Before the cession of Kowloon Peninsula, this territory was governed by Xin'an County. |

| 1 July 1898 | Second Convention of Beijing (Convention for the Extension of Hong Kong Territory) | Lease of the New Territories | South of the Shenzhen River in Xin'an County, including New Kowloon, Lantau and outlying islands. |

By the early 19th century, the British Empire trade was heavily dependent upon the importation of tea, silk, and porcelain from China.[32][33] While the British exported to China luxury items like clocks, watches, there remained an overwhelming imbalance in trade. China developed a strong demand for silver, which was a difficult commodity for the British to come by in large quantities. The counterbalance of trade came with exports of opium to China, opium being legal in Britain and grown in significant quantities in the UK[34] and later in far greater quantities in India.[35][36][37]

A Chinese commissioner Lin Zexu voiced to Queen Victoria the Qing state's opposition to the opium trade. The First Opium War which ensued lasted from 1839 to 1842. Britain occupied the island of Hong Kong on 25 January 1841 and used it as a military staging point. China was defeated and was forced to cede Hong Kong to Britain in the Treaty of Nanking signed on 29 August 1842. Hong Kong became a Crown Colony of the British Empire.

Christian missionaries founded many schools and churches in Hong Kong. St Stephen's Anglican Church located in West Point was founded by the Church Mission Society in 1865. Ying Wa Girls' School located in Mid-levels was founded by the London Missionary Society in 1900. The Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese was founded by the London Missionary Society in 1887, and Sun Yat-sen was one of its first two graduates in 1892. The college was the forerunner of the School of Medicine of the University of Hong Kong, which was established in 1911.

Along with fellow students Yeung Hok-ling, Chan Siu-bak and Yau Lit, Sun Yat-sen started to promote the thought of overthrowing the Qing empire while he studied in the Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese. The four students were known by the Qing as the Four Bandits. Sun attended To Tsai Church (道濟會堂, founded by the London Missionary Society in 1888) while he studied in this College. Sun led the Chinese Revolution of 1911, which changed China from an empire to a republic.

In April 1899, the residents of Kam Tin rebelled against the colonial government. They defended themselves in Kat Hing Wai, a walled village. After several unsuccessful attacks by the British troops, the iron gate was blasted open. The gate was then shipped to London for exhibition. Under the demand of the Tang clan in 1924, the gate was eventually returned in 1925 by the 16th governor, Sir Reginald Stubbs.

Soon after the first gas company in 1862 came the first electric company in 1890. Rickshaws gave way to buses, ferries, trams and airlines.[38] Every industry went through major transformation and growth. Western-style education made advances through the efforts of Frederick Stewart.[39] This was a crucial step in separating Hong Kong from mainland China during the political turmoil associated with the falling Qing dynasty. The seeds of the future financial city were sown with the first large scale bank.[40]

The Third Pandemic of Bubonic Plague attacked Hong Kong in 1894. It provided the pretext for racial zoning with the creation of Peak Reservation Ordinance[41] and recognising the importance of the first hospital.

On the outbreak of World War I in 1914, fear of a possible attack on the colony led to an exodus of 60,000 Chinese. However, Hong Kong's population continued to boom in the following decades from 530,000 in 1916 to 725,000 in 1925. Nonetheless the crisis in mainland China in the 1920s and 1930s left Hong Kong vulnerable to a strategic invasion from Imperial Japan.

British lease of Kowloon and the New Territories

During the second half of the 19th century, the British had grown increasingly worried about the security of their free port at Hong Kong. It was an isolated island, surrounded by areas still under Chinese control. The British decided the answer would be to lease a buffer zone around Hong Kong that would make the island less vulnerable to invasion.

In 1860, at the end of the Second Opium War, the UK gained a perpetual lease over the Kowloon Peninsula, which is the mainland Chinese area just across the strait from Hong Kong Island. This agreement was part of the Convention of Beijing that ended that conflict.

In 1898, the British and Chinese governments signed the Second Convention of Peking, which included a 99-year lease agreement for the islands surrounding Hong Kong, called the "New Territories". The lease awarded control of more than 200 surrounding small islands to the British. In return, China received a promise that the islands would be returned to it after 99 years, at the end of the single negotiated term of lease.

On 19 December 1984, British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and Chinese Premier Zhao Ziyang signed the Sino-British Joint Declaration, in which Britain agreed to return not only the New Territories but also Kowloon and Hong Kong itself when the lease term expired. China promised to implement a "One Country, Two Systems" regime, under which for fifty years Hong Kong citizens could continue to practice capitalism and political freedoms forbidden on the mainland.

On 1 July 1997, the lease ended, and the United Kingdom transferred control of Hong Kong and surrounding territories to the People's Republic of China.

Japanese occupation era (1940s)

Hong Kong was occupied by Japan from 23 December 1941 to 15 August 1945. The period, called '3 years and 8 months' halted the economy. The British, Canadians, Indians and the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Forces resisted the Japanese invasion commanded by Sakai Takashi which started on 8 December 1941, eight hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Japan achieved air superiority on the first day of battle and the defensive forces were outnumbered. The British and the Indians retreated from the Gin Drinker's Line and consequently from Kowloon under heavy aerial bombardment and artillery barrage. Fierce fighting continued on Hong Kong Island; the only reservoir was lost. Canadian Winnipeg Grenadiers fought at the crucial Wong Nai Chong Gap, which was the passage between the north and the secluded southern parts of the island.

On 25 December 1941, referred to as Black Christmas by locals, British colonial officials headed by the Governor of Hong Kong, Mark Aitchison Young, surrendered in person at the Japanese headquarters on the third floor of the Peninsula Hotel. Isogai Rensuke became the first Japanese governor of Hong Kong.

During the Japanese occupation, hyper-inflation and food rationing became the norm of daily lives. It became unlawful to own Hong Kong Dollars, which were replaced by the Japanese Military Yen, a currency without reserves issued by the Imperial Japanese Army administration. During the three and half years of occupation by the Japanese, an estimated 10,000 Hong Kong civilians were executed, while many others were tortured, raped, or mutilated.[43] Philip Snow, a prominent historian of the period, said that the Japanese cut rations for civilians to conserve food for soldiers, usually to starvation levels and deported many to famine- and disease-ridden areas of the mainland. Most of the repatriated had come to Hong Kong just a few years earlier to flee the terror of the Second Sino-Japanese War in mainland China.

By the end of the war in 1945, Hong Kong had been liberated by joint British and Chinese troops. The population of Hong Kong had shrunk to 600,000; less than half of the pre-war population of 1.6 million due to scarcity of food and emigration. The communist revolution in China in 1949 led to another population boom in Hong Kong. Thousands of refugees emigrated from mainland China to Hong Kong, and made it an important entrepôt until the United Nations ordered a trade embargo on mainland China due to the Korean War. More refugees came during the Great Leap Forward.

Post Japanese occupation

After the Second World War, the trend of decolonization swept across the world. Still, Britain chose to keep Hong Kong for strategic reasons. In order to consolidate its rule, constitutional changes, the Young Plan, were proposed in response to the trend of decolonization so as to meet the needs of the people. The political and institutional system made only minimal changes due to the political instability in Mainland China at that time (aforementioned) which caused an influx of mainland residents to Hong Kong.

Modern Hong Kong

Modern Hong Kong under British rule (1950s–1997)

1950s

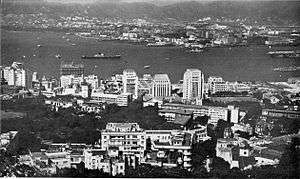

Skills and capital brought by refugees of Mainland China, especially from Shanghai, along with a vast pool of cheap labour helped revive the economy. At the same time, many foreign firms relocated their offices from Shanghai to Hong Kong. Enjoying unprecedented growth, Hong Kong transformed from a territory of entrepôt trade to one of industry and manufacturing. The early industrial centres, where many of the workers spent the majority of their days, turned out anything that could be produced with small space from buttons, artificial flowers, umbrellas, textile, enamelware, footwear to

Large squatter camps developed throughout the territory providing homes for the massive and growing number of immigrants. The camps, however, posed a fire and health hazard, leading to disasters like the Shek Kip Mei Fire. Governor Alexander Grantham responded with a "multi-storey buildings" plan as a standard. It was the beginning of the high rise buildings. Conditions in public housing were very basic with several families sharing communal cooking facilities. Other aspects of life changed as traditional Cantonese opera gave way to big screen cinemas. The tourism industry began to formalise. North Point was known as "Little Shanghai" (小上海), since in the minds of many, it had already become the replacement for the surrendered Shanghai in China.[44]

1960s

The manufacturing industry opened a new decade employing large sections of the population. The period is considered a turning point for Hong Kong's economy. The construction business was also revamped with new detailed guidelines for the first time since World War II. While Hong Kong started out with a low GDP, it used the textile industry as the foundation to boost the economy. China's cultural revolution put Hong Kong on a new political stage. Events like the 1967 riot filled the streets with home-made bombs and chaos. Bomb disposal experts from the police and the British military defused as many as 8,000 home-made bombs. One in every eight bombs was genuine.[45]

Family values and Chinese tradition were challenged as people spent more time in the factories than at home. Other features of the period included water shortages, long working hours coupled with extremely low wages. The Hong Kong Flu of 1968 infected 15% of the population.[46] Amidst all the struggle, "Made in Hong Kong" went from a label that marked cheap low-grade products to a label that marked high-quality products.[47]

1970s

The 1970s saw the extension of government subsidised education from six years to nine years and the setup of Hong Kong's country parks system.

The opening of the mainland Chinese market and rising salaries drove many manufacturers north. Hong Kong consolidated its position as a commercial and tourism centre in Asia. High life expectancy, literacy, per-capita income and other socio-economic measures attest to Hong Kong's achievements over the last four decades of the 20th century. Higher income also led to the introduction of the first high-rise, private housing estates with Taikoo Shing. From this time, people's homes became part of Hong Kong's skyline and scenery.

In 1974, Murray McLehose founded the ICAC, the Independent Commission Against Corruption, in order to combat corruption within the police force. The corruption was so widespread that a mass police petition took place resisting prosecutions. Despite early opposition to the ICAC by the police force, Hong Kong was successful in its anti-corruption efforts, eventually becoming one of the least corrupt societies in the world.

The early 1970s saw legislation requiring equal pay and benefits for equal work by men and women, including the right for married women to be permanent employees.[48][49][50]

1980s

In 1982, the British Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, hoped that the increasing openness of the PRC government and the economic reform in the mainland would allow the continuation of British rule. The resulting meeting led to the signing of Sino-British Joint Declaration and the proposal of the One country, two systems concept by Deng Xiaoping. Political news dominated the media, while real estate took a major upswing. The financial world was also rattled by panics, leading to waves of policy changes and Black Saturday. Meanwhile, Hong Kong was now recognised as one of the wealthiest representatives of the far east. At the same time, the warnings of the 1997 handover raised emigration statistics to historic highs. Many left Hong Kong for the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, Japan, and anywhere else in the world without any communist influence.

Hong Kong's Cinema enjoyed one paramount run that put it on the international map. Some of the biggest names included Jackie Chan and Chow Yun-fat. The music world also saw a new group of cantopop stars like Anita Mui and Leslie Cheung.

1990s

On 4 April 1990, the Hong Kong Basic Law was officially accepted as the mini-constitution of the Hong Kong SAR after the handover. The pro-Beijing bloc welcomed the Basic Law, calling it the most democratic legal system to ever exist in the PRC. The pro-democratic bloc criticised it as not democratic enough. In July 1992, Chris Patten was appointed as the last British Governor of Hong Kong. Patten had been Chairman of the Conservative Party in the UK until he lost his parliamentary seat in the general election earlier that year. Relations with the PRC government in Beijing became increasingly strained, as Patten introduced democratic reforms that increased the number of elected members in the Legislative Council. The PRC government viewed this as a breach of the Basic Law. On 1 July 1997, Hong Kong was handed over to Communist China by the United Kingdom. The old Legislative Council, elected under Chris Patten's reforms, was replaced by the Provisional Legislative Council elected by a selection committee whose members were appointed by the PRC government. Tung Chee Hwa assumed duty as the first Chief Executive of Hong Kong, elected in December by a selection committee with members appointed by the PRC government. He immediately reappointed the entire team of policy secretaries, guaranteeing significant continuity.[51]

| Unchanged after 1997 | Changed after 1997 |

|---|---|

|

|

Modern Hong Kong after the handover (1997–present)

The new millennium signalled a series of events. A sizeable portion of the population that was previously against the handover found itself living with the adjustments. Article 23 became a controversy, and led to marches in different parts of Hong Kong with as many as 750,000 people out of a population of approximately 6,800,000 at the time. The government also dealt with the SARS outbreak in 2003. A further health crisis, the Bird Flu Pandemic (H5N1) gained momentum from the late 90s, and led to the disposal of millions of chickens and other poultry. The slaughter put Hong Kong at the centre of global attention. At the same time, the economy tried to adjust fiscally. Within a short time, the political climate heated up and the Chief Executive position was challenged culturally, politically and managerially. Hong Kong Disneyland, Lantau was also launched during this period. In 2009 Hong Kong suffered from another a flu pandemic which resulted in a school closure for two weeks.

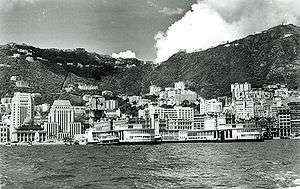

Hong Kong's skylines have continued to evolve, with three new skyscrapers dominating, each in Kowloon, Tsuen Wan and Victoria, Hong Kong. The 415 metre (1,362-feet) tall 88 storey Two International Finance Centre, completed in 2003, previously Hong Kong's tallest building, has been eclipsed by the 484 metre (1,588-feet) tall, 118 storey International Commerce Centre in West Kowloon, which was topped-out in 2010 and remains the tallest skyscraper in Hong Kong. Also worth mentioning is the 320 metre (1,051-feet) tall Nina Tower located in Tsuen Wan. Eight additional skyscrapers over 250 meters (825 feet) have also been completed during this time.[53]

Occupy Central with Love and Peace (OCLP; 讓愛與和平佔領中環 or 和平佔中) was a single-purpose Hong Kong civil disobedience campaign convened by Reverend Chu Yiu-ming, Dr Benny Tai Yiu-ting, and Chan Kin-man on 27 March 2013. Its aim was to pressure the PRC Government into reforming the systems for election of the Hong Kong Chief Executive and Legislative Council so as to satisfy "international standards in relation to universal suffrage" as promised in the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration and Article 45 of the 1997 Hong Kong Basic Law. Its manifesto called for occupation of the region's central business district if such reforms were not made. Upstaged by the Hong Kong Federation of Students (HKFS) and Scholarism in September 2014, its leaders joined in the Occupy Central protests.

The number of impoverished Hongkongers hit a record high in 2016 with one in five people living below the poverty line.[54] Along with housing issues was growing sentiment over the influence of the Chinese Communist Party and Chinese culture. The anti-Hong Kong Express Rail Link movement protested at the proposed Hong Kong section of the Guangzhou-Shenzhen-Hong Kong Express Rail Link; the link was nevertheless completed in 2018. The Hong Kong 818 incident, inhibited by the visit of Li Keqiang, caused controversy regarding civil rights violations. The Moral and National Education controversy exemplified the conflict between communist and nationalist positions of China's government with democratic sentiments expressed by Hong Kong citizens.

The 2016 Legislative council election saw the localists emerging as a new political force behind the pro-Beijing and pan-democracy camps by winning six seats in Hong Kong's geographical constituencies. However, six candidates were barred from contesting by the Electoral Affairs Commission, due to their association with the Hong Kong independence movement. Another six localist members who were elected were disqualified in the Hong Kong Legislative Council oath-taking controversy. After the 5th Hong Kong Chief Executive Election, Carrie Lam became the first female Chief Executive of Hong Kong. However, her proposal of the Fugitive Offenders and Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters Legislation (Amendment) Bill 2019 has led to mass demonstrations against its implementation. The bill would make it legal for China to extradite criminals from Hong Kong, potentially including political prisoners. It is feared that the bill would cause the city to open itself up to the reach of mainland Chinese law and that people from Hong Kong could become subject to a different legal system.

See also

.svg.png)

- History of Colonial Hong Kong (1800s–1930s)

- History of China (timeline)

- History of the People's Republic of China

- British Empire

- British nationality law and Hong Kong

- Secretary of State for War and the Colonies (1801–1854)

- Secretary of State for the Colonies (1768–1782 and 1854–1966)

- Secretary of State for Commonwealth Affairs (1966–1968)

- Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs (since 1968)

- Governor of Hong Kong

- Declared monuments of Hong Kong

- Heritage conservation in Hong Kong

- Museums in Hong Kong

- History of Macau

References

- CIA gov. "CIA." HK GDP 2004. Retrieved on 6 March 2007.

- "Treaty of Nanjing | Definition, Terms, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. 10 April 2009. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- Szczepanski, Kallie (9 June 2020). "Why Did Hong Kong Belong to Britain?". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- "Hong Kong ceded to the British". Sky HISTORY. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- "Japan invades Hong Kong". HISTORY. 16 December 2019. Archived from the original on 28 May 2020. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- "Three Years and Eight Months: Hong Kong during the Japanese Occupation". HKUST Library. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- "Economic History of Hong Kong". eh.net. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- "A Culture of Emigration". www.theatlantic.com. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- Press, Hong Kong Free (31 December 2016). "In Pictures: The 1997 Handover of Hong Kong from Britain to China". Hong Kong Free Press HKFP. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- "Hong Kong's Return To China". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- "China's interference in Hong Kong reaching alarming levels: U.S. congressional panel". Reuters. 17 November 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- Bradsher, Keith (2 July 2003). "Security Laws Target of Huge Hong Kong Protest". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- Kaiman, Jonathan (30 September 2014). "Hong Kong's umbrella revolution - the Guardian briefing". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- Ives, Mike (10 June 2019). "What Is Hong Kong's Extradition Bill?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- "China's new law: Why is Hong Kong worried?". BBC News. 30 June 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- CNN, Jessie Yeung. "What you need to know about Hong Kong's controversial new national security law". CNN. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- Lu, Tracey (30 April 2007). "Report on the Date of the Wong Tei Tung Archaeological Assemblage" (PDF). The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

- "Rescue excavation at Sha Ha, Sai Kung". www.amo.gov.hk. 31 July 2018.

- 2005 Field Archaeology on Sham Chung Site Archived 3 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Meacham, William (2008). The Archaeology of Hong Kong. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 978-9622099258.

- "Nam Viet | ancient kingdom, Asia". Encyclopedia Britannica. 20 July 1998. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- "Hong Kong Museum of History: Lei Cheng Uk Han Tomb". www.lcsd.gov.hk. 30 July 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- "Last emperor: is Shenzhen the resting place of final Song ruler?". South China Morning Post. 7 November 2019. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- "Sung Wong Toi | Hong Kong Tourism Board". Discover Hong Kong. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- Great Britain. Colonial Office, Hong Kong. Government Information Services (1970). Hong Kong. Govt. Press. p. 219.

The Hoklo people, like the Tanka, have been in the area since time unknown. They too are boat-dwellers but are less numerous than the Tanka and are mostly found in eastern waters. In some places, they have lived ashore for several

- Hong Kong: report for the year ... Government Press. 1970. p. 219.

- Grolier Incorporated (1999). The encyclopedia Americana, Volume 14. Grolier Incorporated. p. 474. ISBN 0-7172-0131-7.

In Hong Kong, the Tanka and Hoklo peoples have dwelt in houseboats since prehistoric times. These houseboaters seldom marry shore dwellers. The Hong Kong government estimated that in December 1962 there were 46459 people living on houseboats there, although a typhoon had wrecked hundreds of boats a few months earlier.

- Scholastic Library Publishing (2006). Encyclopedia Americana, Volume 1. Scholastic Library Pub. p. 474. ISBN 0-7172-0139-2.

- The Encyclopedia Americana, Volume 14. Grolier. 1981. p. 474. ISBN 0-7172-0112-0.

- John Thomson 1837–1921, Chap on Hong Kong, Illustrations of China and Its People (London,1873–1874)

- Info Gov HK. "Hong Kong Gov Info Archived 18 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine." History of Hong Kong. Retrieved on 16 February 2007.

- Pritchard, Earl H. (1957). "Private Trade between England and China in the Eighteenth Century (1680-1833)". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 1 (1): 108–137. doi:10.2307/3596041. ISSN 0022-4995.

- "opium trade | History & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. 17 April 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- International Substance Abuse library "http://www.drugtext.org/library/books/opiumpeople/opiuminthefens.html" Retrieved on 26 March 2011.

- "Opium War | National Army Museum". www.nam.ac.uk. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- "5. Opium and the expansion of trade". www.bl.uk. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- Chung, Tan (1973). "THE BRITAIN-CHINA-INDIA TRADE TRIANGLE (1771-1840)". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 34: 77–91. ISSN 2249-1937.

- Wiltshire, Trea. [First published 1987] (republished & reduced 2003). Old Hong Kong - Volume One. Central, Hong Kong: Text Form Asia books Ltd. ISBN Volume One 962-7283-59-2

- Bickley, Gillian. [1997](1997). The Golden Needle: The Biography of Frederick Stewart (1836-1889). Hong Kong. ISBN 962-8027-08-5

- Lim, Patricia. [2002] (2002). Discovering Hong Hong's Cultural Heritage. Central, Hong Kong: Oxford University Press. ISBN Volume One 0-19-592723-0

- Wordie, Jason (2002). Streets: Exploring Hong Kong Island. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. pp. 74–75. ISBN 962-209-563-1.

- Nosowitz, Dan (18 April 2013). "Life Inside The Most Densely Populated Place On Earth [Infographic]". Popular Science. Popular Science. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

1990 50,000 inhabitants

- Carroll 2007, p. 123.

- Wordie, Jason (2002). Streets: Exploring Hong Kong Island. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 962-209-563-1.

- Wiltshire, Trea. [First published 1987] (republished & reduced 2003). Old Hong Kong – Volume Three. Central, Hong Kong: Text Form Asia books Ltd. p. 12. ISBN 962-7283-61-4

- Starling, Arthur (2006). Plague, SARS, and the Story of Medicine in Hong Kong. HK University Press. ISBN 962-209-805-3

- Buckley, Roger. [1997] (1997). Hong Kong: The Road to 1997 By Roger Buckley. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-46979-1

- Toronto SUN Archived 16 July 2012 at Archive.today

- "Celebrating two lives well lived : Featured OTT : Videos". Archived from the original on 4 July 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- SUN, Toronto; Share Life, love and service Tumblr Pinterest Google Plus Reddit LinkedIn Email; Tumblr; Pinterest; Plus, Google; Reddit; LinkedIn; Email; shooting, NewsWoman badly hurt in Etobicoke condo; cause, NewsPOLAR PLUNGE: Cops brave cold in Lake Ontario dip for 'special'; cold, NewsWHEELIE BIG HEARTS: Cops rescue wheelchair-bound man from; ID'd, NewsCRIME SCENE: Fire doused; crook sought; murder victim (7 April 2012). "Life, love and service - Toronto Sun".

- Brian Hook, "British views of the legacy of the colonial administration of Hong Kong: A preliminary assessment," China Quarterly (1997) Issue 151, pp. 553–66

- Wei, Betty; Li, Elizabeth (2008). Culture Shock! Hong Kong. New York: Marshall Cavendish Editions. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-7614-5482-3.

- "Hong Kong - Buildings - EMPORIS". www.emporis.com.

- "Poverty in Hong Kong hits record high with 1 in 5 considered poor". South China Morning Post. 17 November 2017.

Further reading

- Butenhoff, Linda. Social movements and political reform in Hong Kong, Westport: Praeger 1999, ISBN 0-275-96293-8

- Carroll, John M. A Concise History of Hong Kong (2007)

- Clayton, Adam. Hong Kong since 1945: An Economic and Social History (2003)

- Eitel, Ernest John (1895). . London and Hong Kong: Luzac & Co.; Kelly & Walsh – via Wikisource. [scan

- Garver, John W. China's Quest: The History of the Foreign Relations of the People's Republic (2nd ed. 2016) pp 578–606. excerpt

- Hayes, James (1984). "Hong Kong Island Before 1841". Journal of the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 24: 105–142.

- Lui, Adam Yuen-chung (1990). Forts and Pirates – A History of Hong Kong. Hong Kong History Society. p. 114. ISBN 962-7489-01-8.

- Liu, Shuyong; Wang, Wenjiong; Chang, Mingyu (1997). An Outline History of Hong Kong. Foreign Languages Press. p. 291. ISBN 978-7-119-01946-8.

- Ngo, Tak-Wing (1 August 1999). Hong Kong's History: State and Society Under Colonial Rule. Routledge. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-415-20868-0.

- Siu-Kai, Lau. "The Hong Kong Policy of the People's Republic of China, 1949-1997." Journal of Contemporary China 9.23 (2000): 77–93.

- Snow, Philip. The Fall of Hong Kong: Britain, China, and the Japanese Occupation (2004) excerpt and text search

- Tsang, Steve (2007). A Modern History of Hong Kong. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-419-0. excerpt and text search

- Welsh, Frank (1993). A Borrowed place: the history of Hong Kong. Kodansha International. p. 624. ISBN 978-1-56836-002-7.

- Wong, Kam C. Policing in Hong Kong: History and Reform (CRC: Taylor and Francis, 2015)

Primary sources

- Endacott, G. B. (1964). An Eastern Entrepot: A Collection of Documents Illustrating the History of Hong Kong. Her Majesty's Stationery Office. p. 293. ASIN B0007J07G6. OCLC 632495979.

- Tsang, Steve (1995). Government and Politics: A Documentary History of Hong Kong. Hong Kong University Press. p. 312. ISBN 962-209-392-2.

External links

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: History of Hong Kong |

- Hong Kong Museum of History website

- A speech script on history of Hong Kong

- Bibliography of Hong Kong Archaeology on the University of Hong Kong website

- "Story of the Stanford family and the effect of the fall of Hong Kong in 1941."

- Basic Law Drafting History Online -University of Hong Kong Libraries, Digital Initiatives

- Historical Laws of Hong Kong Online - University of Hong Kong Libraries, Digital Initiatives

- Sidney C. H. Cheung, Martyrs, Mystery and Memory Behind the Colonial Shift - Anti-British resistance movement in 1899

- Dr Howard M Scott "Images of Hong Kong - Journal"

- Historical and statistical abstract of the colony of Hongkong (1907)