Baiyue

The Baiyue, Hundred Yue, or simply Yue, were various non-Han Chinese ethnic groups who inhabited the regions of Southern China to Northern Vietnam between the first millennium BC and the first millennium AD.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7] They were known for their short hair, body tattoos, fine swords, and naval prowess.

| Baiyue | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Statue of a man with typical Yue-style short hair and body tattoos, from the state of Yue | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 百越 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Hundred Yue | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese | Bách Việt | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

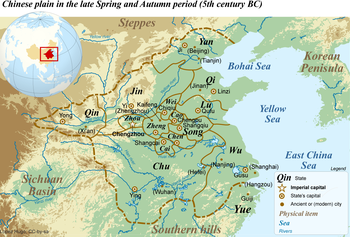

During the Warring States period, the word "Yue" referred to the State of Yue in Zhejiang. The later kingdoms of Minyue in Fujian and Nanyue in Guangdong were both considered Yue states. Meacham (1996:93) notes that, during the Zhou and Han dynasties, the Yue lived in a vast territory from Jiangsu to Yunnan,[6] while Barlow (1997:2) indicates that the Luoyue occupied the southwest Guangxi and northern Vietnam.[8] The Han shu (漢書) describes the lands of Yue as stretching from the regions of Kuaiji (會稽) to Jiaozhi (交趾).[9]

The Yue tribes were gradually displaced or assimilated into Chinese culture as the Han empire expanded into what is now Southern China and Northern Vietnam.[10][11][12][13][14] Many modern southern Chinese dialects bear traces of substrate languages originally spoken by the ancient Yue. Variations of the name are still used for the name of modern Vietnam, in Zhejiang-related names including Yue opera, the Yue Chinese language, and in the abbreviation for Guangdong.

Names

The modern term "Yue" (Chinese: 越 or 粵; pinyin: Yuè; Cantonese Yale: Yuht; Wade–Giles: Yüeh4; Vietnamese: Việt; Early Middle Chinese: Wuat) comes from Old Chinese *ɢʷat (William H. Baxter and Laurent Sagart 2014).[15] It was first written using the pictograph "戉" for an axe (a homophone), in oracle bone and bronze inscriptions of the late Shang dynasty (c. 1200 BC), and later as "越".[16] At that time it referred to a people or chieftain to the northwest of the Shang.[6] In the early 8th century BC, a tribe on the middle Yangtze were called the Yángyuè, a term later used for peoples further south.[6] Between the 7th and 4th centuries BC "Yue" referred to the State of Yue in the lower Yangtze basin and its people.[6][16]

The term "Hundred Yue" first appears in the book Lüshi Chunqiu compiled around 239 BC.[17] It was used as a collective term for many non-Huaxia/Han Chinese populations of south and southwest China and northern Vietnam.[6]

Ancient texts mention a number of Yue states or groups. Most of these names survived into early imperial times:

| Chinese | Mandarin | Cantonese (Jyutping) | Vietnamese | Literal meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 於越/于越 | Yūyuè | jyu1 jyut6 | Ư Việt | Yue by Wuyu (first ruler of Yue) |

| 揚越 | Yángyuè | joeng4 jyut6 | Dương Việt | Yue of Yangzhou |

| 東甌 | Dōng'ōu | joeng4 jyut6 | Đông Âu | Eastern Ou |

| 閩越 | Mǐnyuè | man5 jyut6 | Mân Việt | Yue of Min |

| 夜郎 | Yèláng | je6 long4 | Dạ Lang | |

| 南越 | Nányuè | naam4 jyut6 | Nam Việt | Southern Yue |

| 山越 | Shānyuè | saan1 jyut6 | Sơn Việt | Mountain Yue |

| 雒越 | Luòyuè | lok6 jyut6 | Lạc Việt | |

| 甌越 | Ōuyuè | au1 jyut6 | Âu Việt | Yue of Ou |

| 滇越 | Dianyuè | au1 jyut6 | Điền Việt | Yue of Dian |

History

Yuyue

During the early Zhou dynasty, the Chinese came into contact with a people known as the Yuyue or Wuyue, but it's uncertain if they had any connection with the later Yue.[18]

Wu and Yue

The men of Wu and the people of Yue hate each other, but when they are sailing in the same boat and meet with a storm, they will save each other, just like a left hand [helping] a right.[19]

From the 9th century BC, two northern Yue tribes on the southeastern coastline of China, the Gouwu and Yuyue, came under the cultural influence of their northern Chinese neighbours. These two peoples were based in the areas of what is now southern Jiangsu and northern Zhejiang, respectively. Traditional accounts attribute the cultural exchange to Taibo, a Zhou dynasty prince who had self-exiled to the south. During the Spring and Autumn period, the Gouwu founded the state of Wu and the Yuyue the state of Yue. The Wu and Yue peoples hated each other and had an intense rivalry but were indistinguishable from each other to the other Chinese states. It's suggested in some sources that their distinctive appearance made them victims of discrimination abroad.[19]

The northern Wu eventually became the more sinicized of the two states. The royal family of Wu claimed descent from King Wen of Zhou as the founder of their dynasty. King Fuchai of Wu made every effort to assert this claim and was the source of much contention among his contemporaries. Some scholars believe the Wu royalty may have been Chinese and ethnically distinct from the people they ruled.[18] The recorded history of Wu began with King Shoumeng (r. 585-561 BC). He was succeeded in succession by his sons King Zhufan (r. 560-548 BC), King Yuji (r. 547-531 BC), and King Yumei (r. 530-527 BC). The brothers all agreed to exclude their sons from the line of succession and to eventually pass the throne to their youngest brother, Prince Jizha, but when Yumei died, a succession crisis erupted which saw his son King Liao taking the throne. Not much is known about their reigns as Yue history largely concentrates on the last two Wu kings, Helü of Wu, who killed his cousin Liao, and his son Fuchai of Wu.[20]

Records for the southern state of Yue begin with the reign of King Yunchang (d. 497 BC). According to the Records of the Grand Historian, the Yue kings were descended from Shao Kang of the Xia dynasty. According to another source, the kings of Yue were related to the royal family of Chu. Other sources simply name the Yue ruling family as the house of Zou. There is no scholarly consensus on the origin of the Yue or their royalty.[21]

Wu and Yue spent much of the time at war with each other, during which Yue gained a fearsome reputation for its martial valour:

Zhuangzi of Qi wanted to attack Yue, and he discussed this with Hezi. Hezi said: “Our former ruler handed down his instruction: ‘Do not attack Yue, for Yue is [like] a cruel tiger.’” Zhuangzi said: “Even though it was a cruel tiger, now it is already dead.” Hezi reported this to Xiaozi. Xiaozi said: “It may already be dead but people still think it is alive.[22]

Almost nothing is known about the organizational structure of the Wu and Yue states. Wu records only mention its ministers and kings while Yue records only mention its kings, and of these kings only Goujian's life is recorded in any appreciable detail. Goujian's descendants are listed but aside from their succession of each other until 330 BC, when Yue was conquered by Chu, nothing else about them is known. Therefore, the lower echelons of Wu-Yue society remain shrouded in mystery, appearing only in reference to their strange clothing, tattoos, and short hair by northern Chinese states. After the fall of Yue, the ruling family moved south to what is now Fujian and established the kingdom of Minyue. There they stayed, outside the reach of Chinese history until the end of the Warring States period and the rise of the Qin dynasty.[22]

In 512 BC, Wu launched a large expedition against the large state of Chu, based in the Middle Yangtze River. A similar campaign in 506 succeeded in sacking the Chu capital Ying. Also in that year, war broke out between Wu and Yue and continued with breaks for the next three decades. Wu campaigns against other states such as Jin and Qi are also mentioned. In 473 BC, King Goujian of Yue finally conquered Wu and was acknowledged by the northern states of Qi and Jin. In 333 BC, Yue was in turn conquered by Chu.[23]

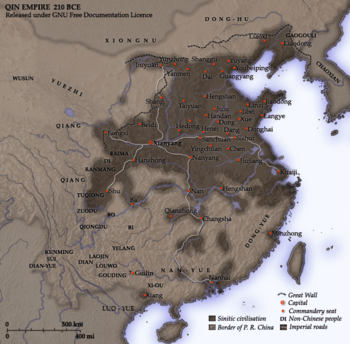

Qin dynasty

After the unification of China by Qin Shi Huang, the former Wu and Yue states were absorbed into the nascent Qin empire. The Qin armies also advanced south along the Xiang River to modern Guangdong and set up commanderies along the main communication routes. Motivated by the region's vast land and valuable exotic products, Emperor Qin Shi Huang is said to have sent half a million troops divided into five armies to conquer the lands of the Yue.[24][25][26] The Yue defeated the first attack by Qin troops and killed the Qin commander.[25] A passage from Huai nan tzu of Liu An quoted by Keith Taylor (1991:18) describing the Qin defeat as follows:[27]

The Yue fled into the depths of the mountains and forests, and it was not possible to fight them. The soldiers were kept in the garrisons to watch over abandoned territories. This went on for a long time, and the soldiers went weary. Then the Yue went out and attacked; the Chi'n (Qin) soldiers suffered a great defeat. Subsequently, convicts were sent to hold the garrisons against the Yue.

Afterwards, Qin Shi Huang sent reinforcements to defend against the Yue. In 214 BC, Qin Shi Huang ordered the construction of the Lingqu Canal, which linked the north and south so that reinforcements could be transported to modern Guangdong, Guangxi and northern Vietnam, which were subjugated and reorganized into three prefectures within the Qin empire.[28] Qin Shi Huang imposed sinicization by sending a large number of Chinese military agricultural colonists to what are now eastern Guangxi and western Guangdong.[29]

Minyue and Dong'ou

When the Qin dynasty fell in 206 BC, the Hegemon-King Xiang Yu did not make Zou Wuzhu and Zou Yao kings. For this reason they refused to support him and instead joined Liu Bang in attacking Xiang Yu. When Liu Bang won the war in 202 BC, he made Zou Wuzhu king of Minyue and in 192 BC, Zou Yao the king of Dong'ou (Eastern Ou).[30] Both Minyue and Dong'ou claimed descent from Goujian.[22]

In 154 BC, Liu Pi, the King of Wu, revolted against the Han and tried to persuade Minyue and Dong'ou to join him. The king of Minyue refused but Dong'ou sided with the rebels. However, when Liu Pi was defeated and fled to Dong'ou, they killed him to appease the Han, and therefore escaped any retaliation. Liu Pi's son, Liu Ziju, fled to Minyue and worked to incite a war between the Minyue and Dong'ou.[30]

In 138 BC, Minyue attacked Dong'ou and besieged their capital. Dong'ou managed to send someone to appeal for help from the Han. Opinions at the Han court were mixed on whether or not to help Dong'ou. Grand commandant Tian Fen was of the opinion that the Yue constantly attacked each other and it was not in the Han's interest to interfere in their affairs. Palace counsellor Zhuang Zhu argued that to not aid Dong'ou would be to signal the end of the empire just like the Qin. A compromise was made to allow Zhuang Zhu to call up troops, but only from Kuaiji Commandery, and finally an army was transported by sea to Dong'ou. By the time the Han forces had arrived, Minyue had already withdrawn its troops. The king of Dong'ou no longer wished to live in Dong'ou, so he requested permission for the inhabitants of his state to move into Han territory. Permission was granted and he and all his people settled in the region between the Changjiang and Huai River.[30][31]

In 137 BC, Minyue invaded Nanyue. An imperial army was sent against them, but the Minyue king was murdered by his brother Zou Yushan, who sued for peace with the Han. The Han enthroned Zou Wuzhu's grandson, Zou Chou, as king. After they left, Zou Yushan secretly declared himself king while the Han backed Zou Chou found himself powerless. When the Han found out about this the emperor deemed it too troublesome to punish Yushan and let the matter slide.[31][32]

In 112 BC, Nanyue rebelled against the Han. Zou Yushan pretended to send forces to aid the Han against Nanyue, but secretly maintained contact with Nanyue and only took his forces as far as Jieyang. Han general Yang Pu wanted to attack Minyue for their betrayal, however the emperor felt that their forces were already too exhausted for any further military action, so the army was disbanded. The next year, Zou Yushan learned that Yang Pu had requested permission to attack him and saw that Han forces were amassing at his border. Zou Yushan made a preemptive attack against the Han, taking Baisha, Wulin, and Meiling, killing three commanders. In the winter, the Han retaliated with a multi-pronged attack by Han Yue, Yang Pu, Wang Wenshu, and two Yue marquises. When Han Yue arrived at the Minyue capital, the Yue native Wu Yang rebelled against Zou Yushan and murdered him. Wu Yang was enfeoffed by the Han as marquis of Beishi. Emperor Wu of Han felt it was too much trouble to occupy Minyue as it was a region full of narrow mountain passes. He commanded the army to evict the region and resettle the people between the Changjiang and Huai River, leaving the region (modern Fujian) a deserted land.[33]

Lạc Việt (Luoyue)

Lạc Việt, known in Chinese as Luoyue, was a conglomeration of Yue tribes in what is now modern Guangxi and northern Vietnam. According to legend, the Lạc Việt founded a state called Văn Lang (Wenlang) in 2879 BC and were ruled by the Hùng kings, who were descended from Lạc Long Quân (Lạc Dragon Lord). Lạc Long Quân came from the sea and subdued all the evil of the land, taught the people how to cultivate rice and wear clothes, and then returned to the sea again. He then met and married Âu Cơ, a fairy, daughter of Đế Lai. Âu Cơ soon bore an egg sac, from which hatched a hundred children. They became ancestors of baiyue tribes. The first born son became Hùng King and ancestor of Luòyuè (Lạc Việt) people.

Despite its legendary origins, Lạc Việt history only begins in the 7th century BC with the first Hùng king in Mê Linh uniting the various tribes. He could use magic.[34]

In 208, the Western Ou (Xi'ou or Nam Cương) king Thục Phán conquered Văn Lang.[35]

Âu Việt (Ouyue)

The Âu Việt, known in Chinese as Ouyue, resided in modern northeast Vietnam, Guangdong province, and Guangxi province. At some point they split and became the Western Ou (Xi'ou or Nam Cương) and the Eastern Ou (Dong'ou). At some point in the late 3rd century BC, Thục Phán, a descendant of the last ruler of Shu, came to rule the Western Ou (Xi'ou or Nam Cương). In 219 BC, Western Ou came under attack from the Qin Empire and lost its king. Seeking refuge, Thục Phán led a group of dispossessed Ou lords south in 208 BC and conquered the Lạc Việt state of Văn Lang, which he renamed Âu Lạc (Ouluo). Henceforth he came to be known as An Dương Vương.[36]

An Dương Vương and the Ou lords built the citadel Cổ Loa, literally "Old Snail"; so called because its walls were laid out in concentric rings reminiscent of a snail shell. According to legend, the construction of the citadel was halted by a group of spirits seeking to gain revenge for the son of the previous king. The spirits were led by a white chicken. A golden turtle appeared, subdued the white chicken, and protected An Dương Vương until the citadel's compleition. When the turtle departed, he left one of his claws behind, which An Dương Vương used as the trigger for his magical crossbow, the "Saintly Crossbow of the Supernaturally Luminous Golden Claw".[27]

An Dương Vương sent a giant called Lý Ông Trọng to the Qin dynasty as tribute. During his stay with the Qin, Lý Ông Trọng distinguished himself in fighting the Xiongnu, after which he returned to his native village and died there.[37]

In 179 BC, An Dương Vương the suzerainty of the Han dynasty, causing Zhao Tuo of Nanyue to become hostile and mobilize forces against Âu Lạc. Zhao Tuo's initial attack was unsuccessful. According to legend, Zhao Tuo asked for a truce ans sent his son to conduct an alliance marriage with An Dương Vương's daughter. Zhao Tuo's son stole the turtle claw that powered An Dương Vương's magical crossbow, rendering his realm without protection. When Zhao Tuo invaded again, An Dương Vương fled into the sea where he was welcomed by the golden turtle. Âu Lạc was divided into the two prefectures of Jiaozhi and Jiuzhen.[38]

Nanyue

Zhao Tuo was a Qin general originally born around 240 BC in the state of Zhao (within modern Hebei). When Zhao was annexed by Qin in 222 BC, Zhao Tuo joined the Qin and served as one of their generals in the conquest of the Baiyue. The territory of the Baiyue was divided into the three provinces of Guilin, Nanhai, and Xiang. Zhao served as magistrate in the province of Nanhai until his military commander, Ren Xiao, fell ill. Before he died, Ren advised Zhao not to get involved in the affairs of the declining Qin, and instead set up his own independent kingdom centered around the geographically remote and isolated city of Panyu (modern Guangzhou). Ren gave Zhao full authority to act as military commander of Nanhai and died shortly afterwards. Zhao immediately closed off the roads at Hengpu, Yangshan, and Huangqi. Using one excuse or another he eliminated the Qin officials and replaced them with his own appointees. By the time the Qin fell in 221 BC, Zhao had also conquered the provinces of Guilin and Xiang. He declared himself King Wu of Nanyue (Southern Yue).[39] Unlike Qin Shi Huang, Zhao respected Yue customs, rallied their local rulers, and let local chieftains continue their old policies and local political traditions. Under Zhao's rule, he encouraged Han Chinese settlers to intermarry with the indigenous Yue tribes through instituting a policy of “Harmonizing and Gathering" while creating a syncretic culture that was a blend of Han and Yue cultures.[25][28]

In 196 BC, Emperor Gaozu of Han dispatched Lu Jia to recognize Zhao Tuo as king of Nanyue.[39] Lu gave Zhao a seal legitimizing him as king of Nanyue in return for his nominal submission to the Han. Zhao received him in the manner of the local people with his hair in a chignon while squatting. Lu accused him of going native and forgetting his true ancestry. Zhao excused himself by saying he had forgotten the northern customs after living in the south for so long.[40]

In 185 BC, Empress Lü's officials outlawed trade of iron and horses with Nanyue. Zhao Tuo retaliated by proclaiming himself Emperor Wu of Nanyue and attacking the neighboring kingdom of Changsha, taking a few border towns. In 181 BC, Zhou Zao was dispatched by Empress Lü to attack Nanyue, but the heat and dampness caused many of his officers and men to fall ill, and he failed to make it across the mountains into enemy territory. Zhao began to menace the neighboring kingdoms of Minyue, Xiou (Western Ou), and Luoluo. After securing their submission he began passing out edicts in a similar manner to the Han emperor.[41]

In 180 BC, Emperor Wen of Han made efforts to appease Zhao. Learning that Zhao's parents were buried in Zhending, he set aside a town close by just to take care of their graves. Zhao's cousins were appointed to high offices at the Han court. He also withdrew the army stationed in Changsha on the Han-Nanyue border. In response, Zhao rescinded his claims to emperorship while communicating with the Han, however he continued using the title of emperor within his kingdom. Tribute bearing envoys from Nanyue were sent to the Han and thus the iron trade was resumed.[42]

In 179 BC, Zhao Tuo defeated the kingdom of Âu Lạc and annexed it.[25]

Zhao Tuo died in 137 BC and was succeeded by his grandson, Zhao Mo.[42] Upon Zhao Mo's accession in 137 BC, the neighboring king of Minyue, Zou Ying, sent his army to attack Nanyue. Zhao sent for help from the Han dynasty, his nominal vassal overlord. The Han responded by sending troops against Minyue, but before they could get there, Zou Ying was killed by his brother Zou Yushan, who surrendered to the Han. The Han army was recalled.[43] Zhao considered visiting the Han court in order to show his gratitude. His high ministers argued against it, reminding him that his father kept his distance from the Han and merely avoided a breach of etiquette to keep the peace. Zhao therefore pleaded illness and never went through with the trip. Zhao did actually fall ill several years later and died in 122 BC. He was succeeded by his son, Zhao Yingqi.[43]

After the Han dynasty aided Nanyue in fending off an invasion by Minyue, Zhao Mo sent his son Yingqi to the Han court, where he joined the emperor's guard (宿衛, Sù wèi). Zhao Yingqi married a Han Chinese woman from the Jiu (樛氏) family of Handan, who gave birth to his second son, Zhao Xing. Yingqi behaved without any scruples and committed murder on several occasions. When his father died in 122 BC, he refused to visit the Han emperor to ask for his leave due to fearing that he would be arrested and punished for his behavior. Yingqi died in 115 BC and was succeeded by his second son, Zhao Xing, rather than the eldest, Zhao Jiande.[44]

In 113 BC, Emperor Wu of Han sent Anguo Shaoji to summon Zhao Xing and the Queen Dowager Jiu to Chang'an for an audience with the emperor. The Queen Dowager Jiu, who was Han Chinese, was regarded as a foreigner by the Yue people, and it was widely rumored that she had an illicit relationship with Anguo Shaoji before she married Zhao Yingqi. When Anguo arrived, quite a number of people believed the two resumed their relationship. The Queen Dowager feared that there would be a revolt against her authority so she urged the king and his ministers to seek closer times to the Han. Xing agreed to and proposed that relations between Nanyue and the Han should be normalized with a triennial journey to the Han court as well as the removal of custom barriers along the border.[45] The prime of Nanyue, minister Lü Jia, held military power and his family was more well connected than either the king or the Queen Dowager. According to the Records of the Grand Historian and Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư, Lü Jia was chief of a Lạc Việt tribe, related to King Qin of Cangwu by marriage, and over 70 of his kinsmen served as officials in various parts of the Nanyue court. Lü refused to meet the Han envoys which angered the Queen Dowager. She tried to kill him at a banquet but was stopped by Xing. The Queen Dowager tried to gather enough support at court to kill Lü in the following months, but her reputation prevented it.[46] When news of the situation reached Emperor Wu in 112 BC, he ordered Zhuang Can to lead a 2,000 men expedition to Nanyue. However Zhuang refused to accept the mission, declaring that it was illogical to send so many men under the pretext of peace, but so few to enforce the might of the Han. The former prime minister of Jibei, Han Qianqiu, offered to lead the expedition and arrest Lü Jia. When Han crossed the Han-Nanyue border, Lü conducted a coup, killing Xing, Queen Dowager Jiu, and all the Han emissaries in the capital. Xing's brother, Zhao Jiande, was declared the new king.[46]

The 2000 men led by Han Qianqiu took several small towns but were defeated as they neared Panyu, which greatly shocked and angered Emperor Wu. The emperor then sent an army of 100,000 to attack Nanyue. The army marched on Panyu in a multi-pronged assault. Lu Bode advanced from the Hui River and Yang Pu from the Hengpu River. Three natives of Nanyue also joined the Han. One advanced from the Li River, the second invaded Cangwu, and the third advanced from the Zangke River. In the winter of 111 BC Yang Pu captured Xunxia and broke through the line at Shimen. With 20,000 men he drove back the vanguard of the Nanyue army and waited for Lu Bode. However Lu failed to meet up on time and when he did arrive, he had no more than a thousand men. Yang reached Panyu first and attacked it at night, setting fire to the city. Panyu surrendered at dawn. Jiande and Lü Jia fled the city by boat, heading east to appeal for Minyue's aid, but the Han learned of their escape and sent the general Sima Shuang after them. Both Jiande and Lü Jia were captured and executed.[47]

Dianyue

In 135 BC, the Han envoy Tang Meng brought gifts to Duotong, the king of Yelang, which bordered the Dian Kingdom, and convinced him to submit to the Han. The Jianwei Commandery was established in the region. In 122 BC, Emperor Wu dispatched four groups of envoys to the southwest in search of a route to Daxia in Central Asia. One group was welcomed by the king of Dian but none of them were able to make it any further as they were blocked in the north by the Sui and Kunming tribes of the Erhai region and in the south by the Di and Zuo tribes. However they learned that further west there was a kingdom called Dianyue where the people rode elephants and traded with the merchants from Shu in secret.[48]

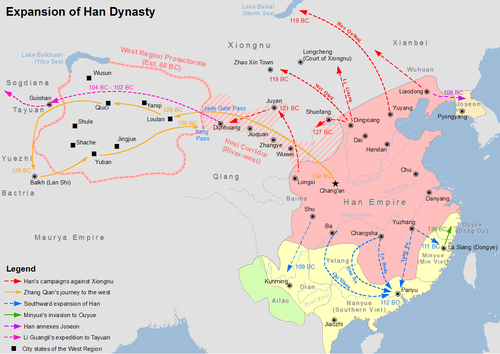

Han dynasty

In 111 BC, the Han dynasty conquered Nanyue (Southern Yue) and ruled it for the next several hundred years.[49][50] The former territory of Nanyue was converted into nine commanderies and two outpost commands.[51][52]

Nanyue was seen as attractive to the Han rulers as they desired to secure the area's maritime trade routes and gain access to luxury goods from the south such as pearls, incense, elephant tusks, rhinoceros horns, tortoise shells, coral, parrots, kingfishers, peacocks, and other rare luxuries to satisfy the demands of the Han aristocracy.[53][54][55] Other considerations such as frontier security, revenue from a relatively large agricultural population, and access to tropical commodities all contributed to the Han dynasty's desire to retain control of the region.[56] Panyu was already a major center for international maritime trade and was one of the most economically prosperous metropolises during the Han dynasty.[57] Regions in the principal ports of modern Guangdong were used for the production of pearls and a trading terminal for maritime silk with Ancient India and the Roman Empire.[57]

Sinicization of the southern Han dynasty which used to be Nanyue was the result of several factors.[58]

Northern and central China was often a theater of imperial dynastic conflict which resulted in waves of Han Chinese refugees fleeing to the south. With dynastic changes, wars, and foreign invasions, Han Chinese living in central China were forced to expand into the unfamiliar and southern regions in large numbers.[2] As the number of Han Chinese immigrants into the Yue coastal regions increased, many Chinese families joined them to escape political unrest, military service, tax obligations, persecution, or sought new opportunities.[59][60] As early arrivals took advantage of the easily accessible fertile land, latecomers had to continue migrating to more remote areas.[2] Conflicts would sometimes arise between the two groups but eventually Han Chinese immigrants from the northern plains moved south to form ad hoc groups and take on the role as powerful local political leaders, many of whom accepted Chinese government titles.[61] Each new wave of Han immigrants exerted additional pressure on the indigenous Yue inhabitants as the Han Chinese in southern China gradually became the predominant ethnic group in local life while displacing the Yue tribes into more mountainous and remote border areas.[62]

The difficulty of logistics and the malarial climate in the south made Han migration and eventual sinicization of the region a slow process.[63][64] Describing the contrast in immunity towards malaria between the indigenous Yue and the Chinese immigrants, Robert B. Marks (2017:145-146) writes:[65] Over the same period, the Han dynasty incorporated many other border peoples such as the Dian and assimilated them.[66] Under the direct rule and greater efforts at sinification by the victorious Han, the territories of the Lac states were annexed and ruled directly, along with other former Yue territories to the north as provinces of the Han empire.[67]

- The Yue population in southern China, especially those who lived in the lower reaches of the river valleys, may have had knowledge of the curative value of the "qinghao" plant, and possibly could also have acquired a certain level of immunity to malaria before Han Chinese even appeared on the scene. But for those without acquired immunity—such as Han Chinese migrants from north China—the disease would have been deadly.

Trưng Sisters

In 40 AD, the Lạc lord Thi Sách rebelled on the advice of his daughter Trưng Trắc. The administrator of Jiaozhi Commandery, Su Ding, was too afraid to confront them and fled. The commanderies of Jiuzhen, Hepu, and Rinan all rebelled. Trưng Trắc abolished the Han taxes and was recognized as queen at Mê Linh. Later Vietnamese sources would claim that her father was killed by the Han, thus stirring her to action, but Chinese sources make it clear Trưng Trắc was always in the leading position alongside her sister Trưng Nhị. Together they came to be known as the legendary Trưng Sisters of Vietnamese history. A large number of names and biographies of leaders under the Trưng Sisters are recorded in temples dedicated to them, many of them also women.[68]

In 41 AD, the veteran Han general Ma Yuan led 20,000 troops against the Trưng Sisters. His advance was checked by Cổ Loa Citadel for over a year, but the Lạc lords became increasingly nervous at the sight of a large Han army. Realizing that she would soon lose her followers if she did not do anything, Trưng Trắc sallied out against the Han army and lost badly, losing more than 10,000 followers. Her followers fled, allowing Ma Yuan to advance. By the end of 42 AD, both sisters had been captured and executed.[69]

Post-rebellion sinicization

After the rebellion of the Trưng Sisters, more direct rule and greater efforts at sinicization were imposed by the Han dynasty. The territories of the Lạc lords were revoked and ruled directly, along with other former Yue territories to the north, as provinces of the Han empire.[70] Division among the Yue leaders were exploited by the Han dynasty with the Han military winning battles against the southern kingdoms and commandaries that were of geographic and strategic value to them. Han foreign policy also took advantage of the political turmoil among rival Yue leaders and enticed them with bribes and lured prospects for submitting to the Han Empire as a subordinate vassal.[71]

Continuing internal Han Chinese migration during the Han dynasty eventually brought all the non-Chinese Yue coastal peoples under Chinese political control and cultural influence.[72] As the number of Han Chinese migrants intensified following the annexation of Nanyue, the Yue people were gradually absorbed and driven out into poorer land on the hills and into the mountains.[73][74][75][76][77] Chinese military garrisons showed little patience with the Yue tribes who refused to submit to Han Chinese imperial power and resisted the influx of Han Chinese immigrants, driving them out to the coastal extremities and the highland areas where they became marginal scavengers and outcasts.[78] Han dynasty rulers saw the opportunity offered by the Chinese family agricultural settlements and used it as a tool for colonizing newly conquered regions and transforming those environments.[79] Displaced Yue tribes often staged sneak attacks and small-scale raids or attacks to reclaim their lost territories on Chinese settlements termed "rebellions" by traditional historians but were eventually stymied by the strong action of the Han dynasty's military superiority.[80][81][82][83][84][2][10][67]

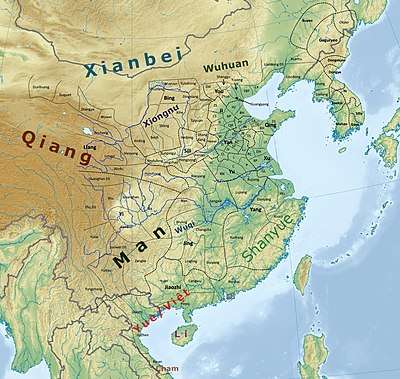

Shanyue

The Shanyue "Mountain Yue" were one of the last groups of Yue mentioned in Chinese history. They lived in the mountain regions of modern Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Anhui, Jiangxi and Fujian.

Yan Baihu, or "White Tiger Yan", was a bandit leader of possibly Shanyue origins. When Sun Ce came to Wu Commandery in 195, Yan Baihu gave refuge to the displaced Xu Gong and threatened the flank of Sun Ce's army. However Sun Ce paid him no attention and the two avoided any altercations. In 197, Cao Cao's agent Chen Yu provoked Yan into rebellion. Sun Ce sent Lü Fan to drive out Chen Yu while he himself attacked Yan. The defeated Yan fled south to join Xu Zhao but died soon afterwards. Remnants of Yan's band joined Xu Gong in 200 to threaten Sun Ce's rear as he attacked Huang Zu in the west. Sun Ce decided to retreat and finish off the bandits once and for all, only to fall into an ambush and die at their hands.[85]

In 203, they rebelled against Sun Quan's rule and were defeated by the generals Lü Fan, Cheng Pu, and Taishi Ci. In 217, Sun Quan appointed Lu Xun supreme commander of an army to suppress martial activities by the Shanyue in Guiji (modern Shaoxing). Captured Shanyue tribesmen were recruited into the army. In 234, Zhuge Ke was made governor of Danyang. Under his governorship, the region was cleansed of the Shanyue through systematic destruction of their settlements. Captured tribesmen were used as front line fodder in the army. The remaining population was resettled in lowlands and many became tenant farmers for Chinese landowners.[86]

Post-Han

The fall of the Han dynasty and the following period of division sped up the process of sinicization. Periods of instability and war in northern and central China, such as the Northern and Southern dynasties and during the Mongol conquest of the Song dynasty sent waves of Han Chinese into the south.[87] Waves of migration and subsequent intermarriage and cross-cultural dialogue gave rise to modern Chinese demographics with a dominant Han Chinese majority and minority non-Han Chinese indigenous peoples in the south.[88][89] By the Tang dynasty (618–907), the term "Yue" had largely become a regional designation rather than a cultural one, as in the Wuyue state during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period in what is now Zhejiang province. During the Song dynasty, a bridge known as the Guojie qiao (World Crossing Bridge) was built at Jiaxing between the modern border of Jiangsu province and Zhejiang province. On the northern side of the bridge stands a statue of King Fuchai of Wu and on the southern side, a statue of King Goujian of Yue.[90] Successive waves of migration in different localities during various times in Chinese history over the past two thousand years have given rise to different dialect groups seen in Southern China today.[91] Modern Lingnan culture contains both Nanyue and Han Chinese elements: the modern Cantonese language resembles Middle Chinese (the prestige language of the Tang Dynasty), but has retained some features of the long-extinct Nanyue language. Some distinctive features of the vocabulary, phonology, and syntax of southern varieties of Chinese are attributed to substrate languages that were spoken by the Yue.[92][93]

Legacy

In ancient China, the characters 越 and 粵 (both yuè in pinyin) were used interchangeably, but they are differentiated in modern Chinese:

- The character "越" refers to the original territory of the state of Yue, which was based in what is now northern Zhejiang, especially the areas around Shaoxing and Ningbo. It is also used to write Vietnam, a word adapted from Nányuè (Vietnamese: Nam Việt), (literal English translation as Southern Yue). This character is also still used in the city Guangzhou for the Yuexiu (越秀) District and when referring to the Nanyue Kingdom.

- The character "粵" is associated with the southern province of Guangdong. Both the regional dialects of Yue Chinese and the standard form, popularly called "Cantonese", are spoken in Guangdong, Guangxi, Hong Kong, Macau and in many Cantonese communities around the world.

Vietnam

Viet is the Vietnamese pronunciation of Yue. The modern name of Vietnam derives from Nanyue, or Nam Việt, except reversed.[94]

Culture

The Ou Yue people have their hair cut short and tattooed bodies, their right shoulder is left bare and their clothes are fastened on the left. In the kingdom of Wu they blacken their teeth and scarify their faces, they wear hats made of fish-skin and [clothes] stitched with an awl.[19]

— Zhanguo Ce

The Han Chinese referred to the various non-Han "barbarian" peoples of southern China as Baiyue, saying they possessed common habits like adapting to water, having their hair cropped short and tattooed. The Han also said their language was "animal shrieking" and that they lacked morals, modesty, civilization and culture.[95][96] According to one Han Chinese immigrant of the 2nd century BC: "The Yue cut their hair short, tattooed their body, live in bamboo groves with neither towns nor villages, possessing neither bows or arrows, nor horses or chariots."[97][98][99] They also blackened their teeth.[100]

Militarily, the ancient states of Yue and Wu were distinct from other Sinitic states for their possession of a navy.[101] Unlike other Chinese states of the time, they also named their boats and swords.[102] A Chinese text described the Yue as a people who used boats as their carriages and oars as their horses.[103] The marshy lands of the south gave the Gouwu and Yuyue people unique characteristics. According to Robert Marks (2017:142), the Yue lived in what is now Fujian province gained their livelihood mostly from fishing, hunting, and practiced some kind of swidden rice farming.[104] Prior to Han Chinese migration from the north, the Yue tribes cultivated wet rice, practiced fishing and slash and burn agriculture, domesticated water buffalo, built stilt houses, tattooed their faces and dominated the coastal regions from shores all the way to the fertile valleys in the interior mountains.[105][106][107][108][109][110] Water transport was paramount in the south, so the two states became advanced in shipbuilding and developed maritime warfare technology mapping trade routes to Eastern coasts of China and Southeast Asia.[111][112]

Swords

The Yue were known for their swordsmanship and producing fine swords. According to the Spring and Autumn Annals of Wu and Yue, King Goujian met a female sword fighter called Nanlin (Yuenü) who demonstrated mastery over the art, and so he commanded his top five commanders to study her technique. Ever since, the technique came to be known as the "Sword of the Lady of Yue". The Yue were also known for their possession of mystical knives embued with the talismanic power of dragons or other amphibious creatures.[113]

The woman was going to travel north to have audience with King [Goujian of Yue] when she met an old man on the road, and he introduced himself as Lord Yuan. He asked the woman: “I have heard that you are good at swordsmanship, I would like to see this.”!e woman said: “I do not dare to conceal anything from you; my lord, you may put me to the test.” Lord Yuan then selected a stave of linyu bamboo, the top of which was withered. He broke off [the leaves] at the top and threw them to the ground, and the woman picked them up [before they hit the ground]. Lord Yuan then grabbed the bottom end of the bamboo and stabbed at the woman. She responded, and they fought they fought three bouts, and just as the woman lifted the stave to strike him, Lord Yuan flew into the treetops and became a white gibbon (yuan).[114]

The Zhan Guo Ce mentions the high quality of southern swords and their ability to cleave through oxen, horses, bowls, and basins, but would shatter if used on a pillar or rock. Wu and Yue swords were highly valued and those who owned them would hardly ever use them for fear of damage, however in Wu and Yue these swords were commonplace and treated with less reverence.[115] The Yuejue shu (Record of Precious Swords) mentions several named swords: Zhanlu (Black), Haocao (Bravery), Juque (Great Destroyer), Lutan (Dew Platform), Chunjun (Purity), Shengxie (Victor over Evil), Yuchang (Fish-belly), Longyuan (Dragon Gulf), Taie (Great Riverbank), and Gongbu (Artisanal Display). Many of these were made by the Yue swordsmith Ou Yezi.[116]

Swords held a special place in the culture of the ancient kingdoms of Wu and Yue. Legends about swords were recorded here far earlier and in much greater detail than any other part of China, and this reflects both the development of sophisticated sword-making technology in this region of China, and the importance of these blades within the culture of the ancient south. Both Wu and Yue were famous among their contemporaries for the quantity and quality of the blades that they produced, but it was not until much later, during the Han dynasty, that legends about them were first collected. These tales became an important part of Chinese mythology, and introduced the characters of legendary swordsmiths such as Gan Jiang 干將 and Mo Ye 莫耶 to new audiences in stories that would be popular for millennia. These tales would serve to keep the fame of Wu and Yue sword-craft alive, many centuries after these kingdoms had vanished, and indeed into a time when swords had been rendered completely obsolete for other than ceremonial purposes by developments in military technology.[117]

— Olivia Milburn

Even after Wu and Yue was assimilated into larger Chinese polities, memory of their swords lived on. During the Han dynasty, Liu Pi King of Wu (195-154 BC) had a sword named Wujian to honour the history of metalworking in his kingdom.[118]

The Sword of Goujian

The Sword of Goujian Inscription on the Sword of Goujian

Inscription on the Sword of Goujian Miniature model of a Yue ship

Miniature model of a Yue ship

Language

Knowledge of Yue speech is limited to fragmentary references and possible loanwords in other languages, principally Chinese. The longest is the Song of the Yue Boatman, a short song transcribed phonetically in Chinese characters in 528 BC and included, with a Chinese version, in the Garden of Stories compiled by Liu Xiang five centuries later.[119]

There is some disagreement about the languages the Yue spoke, with candidates drawn from the non-Sinitic language families still represented in areas of southern China, pre-Kra–Dai, pre-Hmong–Mien and Austroasiatic;[120] as Chinese, Kra–Dai, Hmong–Mien and the Vietic branch of Austroasiatic have similar tone systems, syllable structure, grammatical features and lack of inflection, but these features are believed to have spread by means of diffusion across the Mainland Southeast Asia linguistic area, rather than indicating common descent.[121][122]

- Scholars in China often assume that the Yue spoke an early form of Kra–Dai. The linguist Wei Qingwen gave a rendering of the "Song of the Yue boatman" in Standard Zhuang. Zhengzhang Shangfang proposed an interpretation of the song in written Thai (dating from the late 13th century) as the closest available approximation to the original language, but his interpretation remains controversial.[119][123]

- Chamberlain (1998) posits that the Austroasiatic predecessor of modern Vietnamese language originated in modern-day Bolikhamsai Province and Khammouane Province in Laos as well as parts of Nghệ An Province and Quảng Bình Province in Vietnam, rather than in the region north of the Red River delta.[124] However, Ferlus (2009) showed that the inventions of pestle, oar and a pan to cook sticky rice, which is the main characteristic of the Đông Sơn culture, correspond to the creation of new lexicons for these inventions in Northern Vietic (Việt–Mường) and Central Vietic (Cuoi-Toum).[125] The new vocabularies of these inventions were proven to be derivatives from original verbs rather than borrowed lexical items. The current distribution of Northern Vietic also correspond to the area of Đông Sơn culture. Thus, Ferlus concludes that the Northern Vietic (Viet-Muong) speakers are the "most direct heirs" of the Dongsonians, who have resided in Southern part of Red river delta and North Central Vietnam since the 1st millennium BC.[125]

Wolfgang Behr (2002) points out that some scattered non-Sinitic words found in the two ancient Chinese fictional texts, Mu tianzi zhuan (4th c. BC) and Yuejue shu 越絕書 (1st c. AD), can be compared to lexical items in Kra–Dai languages.[126] For example, Chinese transcribed the Wú words for:

- "Good" (善) with 伊 OC *bq(l)ij; comparable to proto-Tai *ʔdɛiA1 and Proto-Kam-Sui *ʔdaai1 "good";

- "Way" (道) with 缓 OC *awan; comparable to proto-Tai *xronA1, proto-Kam-Sui *khwən "road, way", Proto-Hlai *kuun; confer proto-Austronesian *Zalan (Thurgood 1994:353).

Behr (2009) also notes that the Chǔ dialect was influenced by three substrata, predominantly Kra-Dai, but also possibly Austroasiatic and Hmong-Mien.[127]

Besides a limited number of lexical items left in Chinese historical texts, remnants of language(s) spoken by the ancient Yue can be found in non-Han substrata in Southern Chinese dialects, e.g.: Wu, Min, Hakka, Yue, etc.

- Robert Bauer (1987) identifies twenty seven lexical items in Yue, Hakka and Min varieties, which share Kra–Dai roots.[128] Bauer (1996) also points out twenty nine possible cognates between Cantonese spoken in Guangzhou and Kra–Dai, of which seven cognates are confirmed to originate from Kra–Dai sources.[129] Li Hui (2001) identifies 126 Kra–Dai cognates in Maqiao Wu dialect spoken in the suburbs of Shanghai out of more than a thousand lexical items surveyed.[130] According to the author, these cognates are likely traces of 'old Yue language' (古越語).[131]

- Several authors pointed out the possible link between Hmongic She (畬) and Hakka Chinese.[132][133][134][135]

- Ye (2014) identified a few Austroasiatic loanwords in Ancient Chu dialect.[136]

Jerry Norman and Mei Tsu-Lin presented evidence that at least some Yue spoke an Austroasiatic language:[16][137][138]

- A well-known loanword into Sino-Tibetan[139] is k-la for tiger (Hanzi: 虎; Old Chinese (ZS): *qʰlaːʔ > Mandarin pinyin: hǔ, Sino-Vietnamese hổ) from Proto-Austroasiatic *kalaʔ (compare Vietic *k-haːlʔ > kʰaːlʔ > Vietnamese khái & Muong khảl).

- The early Chinese name for the Yangtze (Chinese: 江; pinyin: jiāng; EMC: kœ:ŋ; OC: *kroŋ; Cantonese: "kong") was later extended to a general word for "river" in south China. Norman and Mei suggest that the word is cognate with Vietnamese sông (from *krong) and Mon kruŋ "river".

- They also provide evidence of an Austroasiatic substrate in the vocabulary of Min Chinese.[16][140]

Norman & Mei's hypothesis is widely quoted, but has recently been criticized by Laurent Sagart who suggests that Yue language, together with proto-Austronesian languages, was descended from the language or languages of the Tánshíshān‑Xītóu culture complex (modern day Fujian province of China); he also argues that the Vietic cradle must be located farther south in current north Vietnam.[141]

- According to the Shuowen Jiezi (100 AD), "In Nanyue, the word for dog is (Chinese: 撓獀; pinyin: náosōu; EMC: nuw-ʂuw)", possibly related to other Austroasiatic terms. Sōu is "hunt" in modern Chinese. However, in Shuowen Jiezi, the word for dog is also recorded as 獶獀 with its most probable pronunciation around 100 CE must have been *ou-sou, which resembles proto-Austronesian *asu, *u‑asu 'dog' than it resembles the palatal‑initialed Austroasiatic monosyllable Vietnamese chó, Old Mon clüw, etc.[123]

- Norman & Mei also compares Min verb "to know, to recognize" 捌 (Proto-Min *pat; whence Fuzhou /paiʔ˨˦/ & Amoy /pat̚˧˨/) to Vietnamese biết, also meaning "to know, to recognize". However, Sagart contends that the Min & Vietnamese sense "to know, to recognize" is semantically extended from well-attested Chinese verb 別 "to distinguish, discriminate, differentiate" ((Mandarin: bié; MC: /bˠiɛt̚/; OC: *bred);[142] thus Sagart considers Vietnamese biết as a loanword from Chinese.

See also

- Hundred Pu (百濮), collective name for non-Sinitic people living in upper Yangtze river.

- Southern Man

- Sanmiao (三苗; Sān Miáo; 'Three Miao')

- Rau peoples

References

- Diller, Anthony; Edmondson, Jerry; Luo, Yongxian (2008). The Tai-Kadai Languages. Routledge (published August 20, 2008). p. 9. ISBN 978-0700714575.

- Hsu, Cho-yun; Lagerwey, John (2012). Y. S. Cheng, Joseph (ed.). China: A Religious State. Columbia University Press (published June 19, 2012). pp. 193–194.

- Holcombe, Charles (2001). The Genesis of East Asia: 221 B.C. - A.D. 907. University of Hawaii Press (published May 1, 2001). p. 150. ISBN 978-0824824655.

- Diller, Anthony (2011). The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Linguistics. Routledge. p. 11. ISBN 978-0415688475.

- Wang, William (2015). The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Linguistics. Oxford University Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-0199856336.

- Meacham, William (1996). "Defining the Hundred Yue". Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. 15: 93–100. doi:10.7152/bippa.v15i0.11537.

- Barlow, Jeffrey G. (1997). "Culture, ethnic identity, and early weapons systems: the Sino-Vietnamese frontier". In Tötösy de Zepetnek, Steven; Jay, Jennifer W. (eds.). East Asian cultural and historical perspectives: histories and society—culture and literatures. Research Institute for Comparative Literature and Cross-Cultural Studies, University of Alberta. pp. 1–15. ISBN 978-0-921490-09-8.

- Barlow, Jeffrey G. (1997). "Culture, ethnic identity, and early weapons systems: the Sino-Vietnamese frontier". In Tötösy de Zepetnek, Steven; Jay, Jennifer W. (eds.). East Asian cultural and historical perspectives: histories and society—culture and literatures. Research Institute for Comparative Literature and Cross-Cultural Studies, University of Alberta. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-921490-09-8.

- Brindley 2003, p. 13.

- Carson, Mike T. (2016). Archaeological Landscape Evolution: The Mariana Islands in the Asia-Pacific Region. Springer (published June 18, 2016). p. 23. ISBN 978-3319313993.

- Wiens, Herold Jacob (1967). Han Chinese expansion in South China. Shoe String Press. p. 276.

- Hutcheon, Robert (1996). China-Yellow. The Chinese University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-9622017252.

- Marks, Robert B. (2011). China: An Environmental History. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 127. ISBN 978-1442212756.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2001). Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War: A Political, Social, and Military History. Oxford University Press. p. 350. ISBN 978-0195135251.

- Old Chinese pronunciation from Baxter, William H. and Laurent Sagart. 2014. Old Chinese: A New Reconstruction. Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-994537-5. These characters are both given as gjwat in Grammata Serica Recensa 303e and 305a.

- Norman, Jerry; Mei, Tsu-lin (1976). "The Austroasiatics in Ancient South China: Some Lexical Evidence" (PDF). Monumenta Serica. 32: 274–301. doi:10.1080/02549948.1976.11731121. JSTOR 40726203.

- The Annals of Lü Buwei, translated by John Knoblock and Jeffrey Riegel, Stanford University Press (2000), p. 510. ISBN 978-0-8047-3354-0. "For the most part, there are no rulers to the south of the Yang and Han Rivers, in the confederation of the Hundred Yue tribes."

- Milburn 2010, p. 5.

- Milburn 2010, p. 2.

- Milburn 2010, p. 6-7.

- Milburn 2010, p. 7.

- Milburn 2010, p. 9.

- Brindley 2003, pp. 1–32.

- Hoang, Anh Tuan (2007). Silk for Silver: Dutch-Vietnamese relations, 1637–1700. Brill Academic Publishing. p. 12. ISBN 978-90-04-15601-2.

- Howard, Michael C. (2012). Transnationalism in Ancient and Medieval Societies: The Role of Cross-Border Trade and Travel. McFarland Publishing. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-7864-6803-4.

- Holcombe, Charles (2001). The Genesis of East Asia: 221 B.C. – A.D. 907. University of Hawaii Press (published May 1, 2001). p. 147. ISBN 978-0-8248-2465-5.

- Taylor 1991, p. 18.

- Him & Hsu (2004), p. 5.

- Huang, Pingwen. "Sinification of the Zhuang People, Culture, And Their Language" (PDF). SEALS. XII: 91.

- Watson 1993, p. 220-221.

- Whiting 2002, p. 145.

- Watson 1993, p. 222.

- Watson 1993, p. 224.

- Taylor 1991, p. 2.

- Milburn 2010, p. 16.

- Taylor 1991, p. 16.

- Taylor 191, p. 18.

- Taylor 1991, p. 20.

- Watson 1993, p. 208.

- Taylor 1991, p. 19.

- Watson 1993, p. 209.

- Watson 1993, p. 210.

- Watson 1993, p. 211.

- Watson 1993, p. 212.

- Watson 1993, p. 213.

- Watson 1993, p. 214.

- Watson 1993, p. 216.

- Watson 1993, p. 236.

- Brindley, Erica Fox (2015). Ancient China and the Yue: Perceptions and Identities on the Southern Frontier, c.400 BCE–50 CE. Cambridge University Press. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-1-316-35228-1.

- Suryadinata, Leo (1997). Ethnic Chinese As Southeast Asians. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 268.

- Xu, Stella (2016). Reconstructing Ancient Korean History: The Formation of Korean-ness in the Shadow of History. Lexington Books (published May 12, 2016). p. 27. ISBN 978-1-4985-2144-4.

- Miksic, John Norman; Yian, Goh Geok (2016). Ancient Southeast Asia. Routledge (published October 27, 2016). p. 157. ISBN 978-0-415-73554-4.

- Kiernan, Ben (2017). A History of Vietnam, 211 BC to 2000 AD. Oxford University Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-19-516076-5.

- Miksic, John Norman; Yian, Goh Geok (2016). Ancient Southeast Asia. Routledge (published October 27, 2016). p. 158. ISBN 978-0-415-73554-4.

- Higham, Charles (1989). The Archaeology of Mainland Southeast Asia: From 10,000 B.C. to the Fall of Angkor. Cambridge University Press. p. 289. ISBN 978-0-521-27525-5.

- Taylor 1991, p. 21.

- H. Brill, Robert; Gan, Fuxi (2009). Tian, Shouyun (ed.). Ancient Glass Research Along the Silk Road. World Scientific Publishing (published March 13, 2009). p. 169.

- Taylor 1991, p. 24.

- Hashimoto, Oi-kan Yue (2011). Studies in Yue Dialects 1: Phonology of Cantonese. Cambridge University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0521189828.

- Stuart-Fox, Martin (2003). A Short History of China and Southeast Asia: Tribute, Trade and Influence. Allen & Unwin (published November 1, 2003). pp. 24–25.

- Hsu, Cho-yun; Lagerwey, John (2012). Y. S. Cheng, Joseph (ed.). China: A Religious State. Columbia University Press (published June 19, 2012). p. 241.

- Weinstein, Jodi L. (2013). Empire and Identity in Guizhou: Local Resistance to Qing Expansion. University of Washington Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0295993270.

- Marks 2017, pp. 144-146.

- Hutcheon, Robert (1996). China-Yellow. The Chinese University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-962-201-725-2.

- Marks 2017, pp. 145-146.

- Anderson, David (2005). The Vietnam War (Twentieth Century Wars). Palgrave. ISBN 978-0333963371.

- McLeod, Mark; Nguyen, Thi Dieu (2001). Culture and Customs of Vietnam. Greenwood (published June 30, 2001). p. 15-16. ISBN 978-0313361135.

- Taylor 1991, p. 30-31.

- Taylor 1991, p. 32.

- McLeod, Mark; Nguyen, Thi Dieu (2001). Culture and Customs of Vietnam. Greenwood (published June 30, 2001). pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-0-313-36113-5.

- Brindley 2015, pp. 249.

- Stuart-Fox, Martin (2003). A Short History of China and Southeast Asia: Tribute, Trade and Influence. Allen & Unwin (published November 1, 2003). p. 18.

- Marks, Robert B. (2011). China: An Environmental History. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-4422-1275-6.

- Crooks, Peter; Parsons, Timothy H. (2016). Empires and Bureaucracy in World History: From Late Antiquity to the Twentieth Century. Cambridge University Press (published August 11, 2016). pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-1-107-16603-5.

- Ebrey, Patricia; Walthall, Anne (2013). East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. Wadsworth Publishing (published January 1, 2013). p. 53. ISBN 978-1-133-60647-5.

- Peterson, Glen (1998). The Power of Words: Literacy and Revolution in South China, 1949-95. University of British Columbia Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-7748-0612-1.

- Michaud, Jean; Swain, Margaret Byrne; Barkataki-Ruscheweyh, Meenaxi (2016). Historical Dictionary of the Peoples of the Southeast Asian Massif. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers (published October 14, 2016). p. 163. ISBN 978-1-4422-7278-1.

- Hutcheon, Robert (1996). China-Yellow. The Chinese University Press. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-962-201-725-2.

- Marks, Robert B. (2011). China: An Environmental History. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 339. ISBN 978-1-4422-1275-6.

- Walker, Hugh Dyson (2012). East Asia: A New History. AuthorHouse. p. 93.

- "Yue 越, Baiyue 百越, Shanyue 山越". China Knowledge. August 17, 2012.

- Siu, Helen (2016). Tracing China: A Forty-Year Ethnographic Journey. Hong Kong University Press. p. 231. ISBN 978-9888083732.

- Marks, Robert B. (2017). China: An Environmental History. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 143. ISBN 978-1442277878.

- Hsu, Cho-yun; Lagerwey, John (2012). Y. S. Cheng, Joseph (ed.). China: A Religious State. Columbia University Press (published June 19, 2012). pp. 240–241.

- de Crespigny 2007, p. 938.

- "Yue 越 (WWW.chinaknowledge.de)".

- Gernet, Jacques (1996). A History of Chinese Civilization (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-49781-7.

- de Sousa (2015), p. 363.

- Wen, Bo; Li, Hui; Lu, Daru; Song, Xiufeng; Zhang, Feng; He, Yungang; Li, Feng; Gao, Yang; Mao, Xianyun; Zhang, Liang; Qian, Ji; Tan, Jingze; Jin, Jianzhong; Huang, Wei; Deka, Ranjan; Su, Bing; Chakraborty, Ranajit; Jin, Li (2004). "Genetic evidence supports demic diffusion of Han culture". Nature. 431 (7006): 302–305. Bibcode:2004Natur.431..302W. doi:10.1038/nature02878. PMID 15372031.

- Milburn 2010, p. 1.

- Crawford, Dorothy H.; Rickinson, Alan; Johannessen, Ingolfur (2014). Cancer Virus: The story of Epstein-Barr Virus. Oxford University Press (published March 14, 2014). p. 98.

- de Sousa (2015), pp. 356–440.

- Yue-Hashimoto, Anne Oi-Kan (1972). Studies in Yue Dialects 1: Phonology of Cantonese. Cambridge University Press. pp. 14–32. ISBN 978-0-521-08442-0.

- Taylor 1991, p. 34.

- Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association, Issue 15. Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. 1996. p. 94.

- Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. Congress (1996). Indo-Pacific Prehistory: The Chiang Mai Papers, Volume 2. Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. Volume 2 of Indo-Pacific Prehistory: Proceedings of the 15th Congress of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 5–12 January 1994. The Chiang Mai Papers. Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association, Australian National University. p. 94.

- Kiernan, Ben (2017). A History of Vietnam, 211 BC to 2000 AD. Oxford University Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0195160765.

- Hutcheon, Robin (1996). China–Yellow. Chinese University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-962-201-725-2.

- Mair, Victor H.; Kelley, Liam C. (2016). Imperial China and Its Southern Neighbours. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (published April 28, 2016). pp. 25–33.

- Milburn 2010, p. 1-2.

- Holm 2014, p. 35.

- Kiernan 2017, pp. 49-50.

- Kiernan 2017, p. 50.

- Marks (2017), p. 142.

- Sharma, S. D. (2010). Rice: Origin, Antiquity and History. CRC Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-57808-680-1.

- Brindley 2015, p. 66.

- Him & Hsu (2004), p. 8.

- Peters, Heather (April 1990). H. Mair, Victor (ed.). "TATTOOED FACES AND STILT HOUSES: WHO WERE THE ANClENT YUE?" (PDF). Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations. East Asian Collection. Sino-Platonic Papers. 17: 3.

- Marks (2017), p. 72.

- Marks (2017), p. 62.

- Lim, Ivy Maria (2010). Lineage Society on the Southeastern Coast of China. Cambria Press. ISBN 978-1604977271.

- Lu, Yongxiang (2016). A History of Chinese Science and Technology. Springer. p. 438. ISBN 978-3-662-51388-0.

- Brindley 2015, p. 181-183.

- Milburn 2010, p. 291.

- Milburn 2010, p. 247.

- Milburn 2010, p. 285.

- Milburn 2010, p. 273.

- Milburn 2010, p. 276.

- Zhengzhang, Shangfang (1991). "Decipherment of Yue-Ren-Ge (Song of the Yue boatman)". Cahiers de Linguistique Asie Orientale. 20 (2): 159–168. doi:10.3406/clao.1991.1345.

- DeLancey, Scott (2011). "On the Origins of Sinitic". Proceedings of the 23rd North American Conference on Chinese Lingusitic. Studies in Chinese Language and Discourse. 1. pp. 51–64. doi:10.1075/scld.2.04del. ISBN 978-90-272-0181-2.

- Enfield, N.J. (2005). "Areal Linguistics and Mainland Southeast Asia" (PDF). Annual Review of Anthropology. 34: 181–206. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.34.081804.120406. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0013-167B-C. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-24. Retrieved 2013-06-05.

- LaPolla, Randy J.. (2010). Language Contact and Language Change in the History of the Sinitic Languages. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2(5), 6858-6868.

- Sagart 2008, p. 143.

- Chamberlain, J.R. 1998, "The origin of Sek: implications for Tai and Vietnamese history", in The International Conference on Tai Studies, ed. S. Burusphat, Bangkok, Thailand, pp. 97-128. Institute of Language and Culture for Rural Development, Mahidol University.

- Ferlus, Michael (2009). "A Layer of Dongsonian Vocabulary in Vietnamese" (PDF). Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society. 1: 95–108.

- Behr 2002.

- Behr, Wolfgang (2009). "Dialects, diachrony, diglossia or all three? Tomb text glimpses into the language(s) of Chǔ", TTW-3, Zürich, 26.-29.VI.2009, “Genius loci”

- Bauer, Robert S. (1987). 'Kadai loanwords in southern Chinese dialects', Transactions of the International Conference of Orientalists in Japan 32: 95–111.

- Bauer (1996), pp. 1835-1836.

- Li 2001, p. 15.

- Li 2001.

- Sagart, Laurent. (2002). Gan, Hakka and the formation of Chinese dialects. In D. A. Ho (Ed.), Dialect variations in Chinese [漢語方言的差異與變化] (pp.129-154). Taipei: Academia Sinica.

- Lo, Seogim. (2006). Origin of the Hakka Language [客語源起南方的語言論證]. Language and Linguistics, 7(2), 545-568.

- Lee, Chyuan-Luh. (2015). The source and fate of She-: She- language, She- words, Hakka words. Journal of Hakka Studies, 8(2), 101-128.

- Lai, Wei-Kai. (2015). The “Hakka-She”basic words are derived from the South Minority: The source of the “Hakka” and “She” Ethnic Name. Journal of Hakka Studies, 8(2), 27-62.

- Ye, Xiaofeng (叶晓锋) (2014). 上古楚语中的南亚语成分 (Austroasiatic elements in ancient Chu dialect). 《民族语文》. 3: 28-36.

- Norman, Jerry (1988). Chinese. Cambridge University Press. pp. 17–19. ISBN 978-0-521-29653-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Boltz, William G. (1999). "Language and Writing". In Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L. (eds.). The Cambridge history of ancient China: from the origins of civilization to 221 B.C.. Cambridge University Press. pp. 74–123. ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8.

- Sino-Tibetan Etymological Dictionary and Thesaurus, http://stedt.berkeley.edu/~stedt-cgi/rootcanal.pl/etymon/5560

- Norman (1988), pp. 18–19, 231

- Sagart 2008, pp. 141-145.

- Sagart 2008, p. 142.

Sources

- Bauer, Robert S. (1996), "Identifying the Tai substratum in Cantonese" (PDF), Proceedings of the Fourth International Symposium on Languages and Linguistics, Pan-Asiatic Linguistics V: 1 806- 1 844, Bangkok: Institute of Language and Culture for Rural Development, Mahidol University at Salaya.

- Behr, Wolfgang (2002). "Stray loanword gleanings from two Ancient Chinese fictional texts". 16e Journées de Linguistique d'Asie Orientale, Centre de Recherches Linguistiques Sur l'Asie Orientale (E.H.E.S.S.), Paris: 1–6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brindley, Erica F. (2015), Ancient China and the Yue, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-107-08478-0.

- Brindley, Erica F. (2003), "Barbarians or Not? Ethnicity and Changing Conceptions of the Ancient Yue (Viet) Peoples, ca. 400–50 BC" (PDF), Asia Major. 16, No. 2: 1–32.

- de Sousa, Hilário (2015), "The Far Southern Sinitic languages as part of Mainland Southeast Asia" (PDF), in Enfield, N.J.; Comrie, Bernard. (eds.), Languages of Mainland Southeast Asia: The State of the Art, Walter de Gruyter, pp. 356–440, ISBN 978-1-5015-0168-5.

- Him, Mark Lai; Hsu, Madeline (2004), Becoming Chinese American: A History of Communities and Institutions, AltaMira Press, ISBN 978-0-759-10458-7.

- Holm, David (2014). "A Layer of Old Chinese Readings in the Traditional Zhuang Script". Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities: 1–45.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kiernan, Ben (2017), Việt Nam: A History from Earliest Times to the Present, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-516076-5.

- Li, Hui (2001). "Daic Background Vocabulary in Shanghai Maqiao Dialect" (PDF). Proceedings for Conference of Minority Cultures in Hainan and Taiwan, Haikou: Research Society for Chinese National History: 15–26.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marks, Robert B. (2017), China: An Environmental History, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 978-1-442-27789-2.

- Milburn, Olivia, The Glory of Yue

- Sagart, Laurent (2008), "The expansion of Setaria farmers in East Asia", in Sanchez-Mazas, Alicia; Blench, Roger; Ross, Malcolm D.; Ilia, Peiros; Lin, Marie (eds.), Past human migrations in East Asia: matching archaeology, linguistics and genetics, Routledge, pp. 133–157, ISBN 978-0-415-39923-4,

Quote: in conclusion, there is no convincing evidence, linguistic or other, of an early Austroasiatic presence on the southeast China coast.

- Taylor, Keith W. (1991), The Birth of Vietnam, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-07417-0.

- Watson, Burton (1993), Records of the Grand Historian by Sima Qian: Han Dynasty II (Revised Edition, Columbia University Press

- Whiting, Marvin C. (2002), Imperial Chinese Military History, Writers Club Press

- von Stella, Xu (2016), Reconstructing Ancient Korean History: The Formation of Korean-ness in the Shadow of History, Lexington Books, ISBN 978-1-4985-2145-1.

External links

- "The power of language over the past: Tai settlement and Tai linguistics in southern China and northern Vietnam", Jerold A. Edmondson, in Studies in Southeast Asian languages and linguistics, ed. by Jimmy G. Harris, Somsonge Burusphat and James E. Harris, 39–64. Bangkok, Thailand: Ek Phim Thai Co. Ltd.