Convention of Chuenpi

The Convention of Chuenpi[1] (also "Chuenpee", pinyin: Chuān bí) was a tentative agreement between British Plenipotentiary Charles Elliot and Chinese Imperial Commissioner Qishan during the First Opium War between the United Kingdom and the Qing dynasty of China. The terms were published on 20 January 1841, but both governments rejected them and dismissed Elliot and Qishan, respectively, from their positions. Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston stated that Elliot acquired too little while the Daoguang Emperor believed Qishan conceded too much. Palmerston appointed Major-General Henry Pottinger to replace Elliot, while the emperor appointed Yang Fang to replace Qishan, along with Yishan as General-in-Chief of Repressing Rebellion and Longwen as an assistant regional commander. Although the convention was unratified, many of the terms were later included in the Treaty of Nanking (1842).

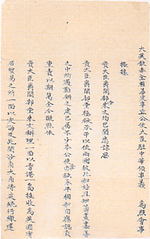

Page one of the convention | |

| Drafted | 20 January 1841 |

|---|---|

| Location | Humen, Guangdong, China |

| Condition | Unratified; superseded by the Treaty of Nanking (1842) |

| Negotiators | Charles Elliot Qishan |

| Convention of Chuenpi | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 穿鼻草約 | ||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 穿鼻草约 | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of Hong Kong |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

| By topic |

|

Background

On 20 February 1840, Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston instructed the joint plenipotentiaries Captain Charles Elliot and his cousin Admiral George Elliot to acquire the cession of at least one island for trade on the Chinese coast, amongst other terms.[2] In November 1840, during the First Opium War, George returned to Britain due to ill health, leaving Charles as sole plenipotentiary. In negotiations with Imperial Commissioner Qishan, Elliot wrote on 29 December to "request a place in the outer sea, where the British can fly their flag and administer themselves, just as the Westerners do in Macao."[3] However, the year ended with no agreement. To force Chinese concessions, the British captured the forts at the entrance of the Humen strait (Bogue) on 7 January 1841, after which Qishan agreed to consider Elliot's demands. Negotiations ensued at the Bogue near Chuenpi.[4]

On 11 January, Qishan offered to "grant a place outside the estuary to lodge temporarily".[3] He later wrote to Elliot on 15 January, offering either Hong Kong Island or Kowloon but not both. Elliot replied the next day, accepting Hong Kong. On 15 January, trader James Matheson wrote to his business partner William Jardine that Elliot arrived in Macao the night before: "I learn from him very confidentially that Ki Shen [Qishan] has agreed to the British having a possession of their own outside, but objects to ceding Chuenpee; in lieu of which Captain Elliot has proposed Hong Kong".[5]

One factor that may have led to settling on Hong Kong was the perceived ambiguity of the Chinese language. Matheson believed that when Qishan wrote "as we have granted you territory you do not now require another port", Elliot as a result gave up demands of British access to a port in northern China in the hope that he could hold Qishan to an interpretation of the Chinese characters in which the British had been ceded Hong Kong rather than just being given a trading factory there.[6][7]

Terms

On 20 January, Elliot issued a circular announcing "the conclusion of preliminary arrangements" between Qishan and himself involving the following conditions:[8]

- The cession of the island and harbour of Hong Kong to the British crown. All just charges and duties to the empire [of China] upon the commerce carried on there to be paid as if the trade were conducted at Whampoa.

- An indemnity to the British government of six millions of dollars, one million payable at once, and the remainder in equal annual instalments ending in 1846.

- Direct official intercourse between the countries upon equal footing.

- The trade of the port of Canton to be opened within ten days after the Chinese new-year, and to be carried on at Whampoa till further arrangements are practicable at the new settlement.

Other terms that were agreed upon were the restoration of the islands of Chuenpi and Taikoktow to the Chinese, and the evacuation of Chusan (Zhoushan), which the British had captured and occupied since July 1840.[9] Chusan was returned in exchange for the release of British prisoners in Ningpo who became shipwrecked on 15 September 1840 after the brig Kite struck quicksand en route to Chusan.[10][11] The convention allowed the Qing government to continue collecting tax at Hong Kong, which was the main sticking point that led to the disagreement according to Lord Palmerston.[12]

Aftermath

The forts were restored to the Chinese on 21 January in a ceremony on Chuenpi, which had been held by Captain James Scott as pro tempore governor of the fort.[4] Commodore Gordon Bremer, commander-in-chief of British forces in China, sent an officer to Anunghoy (north of Chuenpi) with a letter for Chinese Admiral Guan Tianpei, informing him of their intention to return the forts. About an hour later, Guan sent a mandarin to receive them. The British colours were hauled down and the Chinese colours were hoisted in their place, under a salute fired from HMS Wellesley, and returned by the Chinese with a salute fired from the Anunghoy batteries.[14][15] The ceremony was repeated at Taikoktow.[16] Military secretary Keith Mackenzie observed: "I never saw a [Chinese] man in such an ecstasy of chin chin [a gesture of greeting or farewell], as he was, when our colours were lowered—he absolutely jumped for joy."[17]

Two days later, Elliot dispatched the brig Columbine to Chusan, with instructions to evacuate it for Hong Kong. Duplicates of these dispatches were also forwarded overland by the imperial express. At the same time, Qishan directed Yilibu, the viceroy of Liangjiang, to release the British prisoners at Ningpo.[18] News of the terms was sent to England aboard the East India Company steamer Enterprise, which left China on 23 January.[19] On the same day, the Canton Free Press published the opinion of British residents in China regarding the cession of Hong Kong:

We consider that, for an independent British settlement, no situation can possibly be more favourably chosen than that of Hong-Kong. The island itself is of little extent ... but it forms, with the neighbouring lands, one of the finest ports existing ... Hong Kong would, we doubt not, in a very short time, become a place of very considerable trade, were its possession by the British not clogged with the condition that the same duties at Whampoa are to be paid there; which, in our estimation, destroys at once all the benefits that might be expected to trade there.[20]

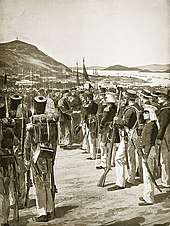

On 26 January 1841, Commodore Bremer took formal possession of Hong Kong with the naval officers of the squadron at Possession Point, where the Union Jack was raised, under a feu de joie from the Royal Marines and a royal salute from the warships.[21]

Banquet

On the same day as the Hong Kong ceremony, Elliot left Macao on board the steamer Nemesis to meet Qishan at Lotus Flower Hill near the Second Bar pagoda to settle the convention.[22][23] 100 marines from the Wellesley, Druid, and Calliope were embarked on board the steamer Madagascar to be Elliot's guard of honour. He was accompanied by several officers, including Lieutenant Anthony Stransham, Captain Thomas Herbert, and Captain Thomas Maitland, as well as the military band of the Wellesley. As the steamers passed through the Bogue, they were saluted with three guns by the forts on both sides. The steamer returned the salute while the band played "God Save the Queen".[24][25] The ships arrived too late in the evening to land, but Qishan sent a few staff who said he would be ready to receive them in the morning.[26]

At 9 am, after boarding the steamers' boats and Chinese boats provided by Qishan, they sailed to the landing place about 0.25 miles (400 m) up a creek.[26] The marine guard was drawn up for Elliot, accompanied by Captain Herbert and Captain Richard Dundas, and preceded by the band before Qishan received the party at his main tent.[27] This was the first time in Sino-British relations that a Chinese high official received a British representative, with a carefully selected suite, not as a "barbarian vassal" but as a plenipotentiary of standing.[28] A series of dishes were served at the luncheon for over 20 people, including the shark's fin and bird's nest soups.[29] Elliot and interpreter John Morrison later had a private meeting with Qishan, who did not sign the convention but agreed to put matters in abeyance until Chusan was evacuated.[28] In the evening, the Nemesis launched a display of rockets and fireworks "for the amusement" of Qishan on shore.[30]

In February 1841, Qishan sent a memorial to the emperor which reached Peking (Beijing) on 16 February. He covered four main topics, summarised as follows:[31][32]

- The forts – Located on small islands and having channels in the rear, foreign ships could easily blockade them and starve out the defenders. Canton can also be reached from other channels, not just the same route followed during peace time.

- The guns – Inadequate in number, with many obsolete and not in working order. They are placed at the front of the forts, leaving the sides undefended.

- The troops – The soldiers being used as marines are unused to ships and those normally employed for patrol duty are sometimes of poor quality.

- The Cantonese people – Even putting aside those considered "traitors", they have generally become so used to the foreigners that they no longer regard them as vastly different people and often get along with them. A small present such as a mechanical contrivance is enough to win over most of the people.

Renewed hostilities

During the meeting on 27 January, the Daoguang Emperor received a memorial Qishan sent on 8 January, reporting on the British capture of the Bogue forts. He instructed Qishan via the Grand Council:

To this display of rebelliousness, the only response can be to suppress them and wipe them out. If they show no reasonableness there is no point in trying to give them orders. You are to lead the commanders and officers and spare no effort in exterminating them, to recover [the lost territory].[3]

The order arrived on 9 February, but Qishan did not change course. In a memorial to the emperor on 14 February, he said he received the order "yesterday" to cover up his continued meetings with Elliot.[33] In favour of a peaceful solution, Qishan defied orders to attack.[34] One of the convention's terms was that the port of Canton was to be opened for trade within 10 days after the Chinese New Year, but no announcement for the opening appeared by 2 February.[9] Elliot and Qishan met again on 11–12 February at Shetouwan near the Bogue.[33] A British account described Qishan's demeanour:

There was an appearance of constraint about him, as if his mind was downcast, and his heart burdened and heavy laden. He never indeed for a moment lost his self-possession, or that dignified courtesy of manner which no people can better assume than the Chinese of rank; but there was still something undefinable in his bearing, which impressed upon all present the conviction that something untoward had happened.[35]

After negotiating for 12 hours, they reached a preliminary agreement, but Qishan asked for 10 days before he would sign it,[33] which Elliot accepted.[9] Under pressure, Qishan had abandoned open resistance in favour of delaying tactics.[33] Commodore Bremer reported that at this time, Chinese troops and cannons were being mobilised around the Bogue.[9] When Qishan returned to Canton on 13 February, there were two documents awaiting him. The first was an edict the emperor sent on 30 January, which stated that a large army would be sent to Canton and appointed Yang Fang as the new imperial commissioner, Yishan as General-in-Chief of Repressing Rebellion, and Longwen as an assistant regional commander. The second was a letter from Elliot with a draft agreement, requesting to meet promptly so they could sign it together. Qishan ran out of options.[33] With his dismissal, he had little choice but to change tack and prepare to fight. On 16 February, Elliot reported that the British withdrew from Chusan and demanded that Qishan sign the agreement otherwise attacks would recommence. In an attempt to delay the British, Qishan claimed illness and needed time to recover.[34]

The Nemesis was dispatched to Canton to receive written ratification of the convention.[36] On 19 February, the ship returned without any reply and came under fire from North Wangtong Island in the Bogue.[9] Meanwhile, Qishan sent his intermediary Bao Peng to deliver a letter with a new concession that same day. Instead of lodging on "only a corner of Hong Kong", the British could "have the whole island".[34] He instructed Bao: "Pay attention to the situation: hand it to them if they are respectful, if they are capricious, do not give it to them."[34] Bao arrived in Macao later that evening, announcing Qishan's refusal to sign the treaty and demanded more time. However, Elliot responded that fair means had been exhausted.[37] The next day, Bao returned with the letter.[34] The British captured the rest of the Bogue forts on 23–26 February, which allowed them to proceed towards Canton to force the opening of trade. As the fleet advanced up the Pearl River towards the city, they captured more forts in the Battle of First Bar (27 February) and Battle of Whampoa (2 March). After capturing Canton on 18 March, the resumption of trade was announced.[38]

Dismissals

After leaving Canton on 12 March,[39] Qishan stood trial at the Board of Punishments in Peking.[40] He faced several charges, including giving "the barbarians Hongkong as a dwelling place", to which he claimed, "I pretended to do so from the mere force of circumstances, and to put them off for a time, but had no such serious intention."[41] The court denounced him as a traitor and sentenced him to death. But after being imprisoned for several months, he was allowed—without official rank—to deal with the British.[42] On 21 April, Lord Palmerston dismissed Elliot, considering the concessions to be inadequate. He felt that Elliot treated his instructions as "waste paper" and dismissed Hong Kong as "a barren island with hardly a house upon it".[43] In May 1841, Major-General Henry Pottinger of the Bombay Army was appointed to replace Elliot. Pottinger was given reinforcements that enlarged the expedition to 25 warships and 12,000 men.[44] Many of the convention's terms were later added in the Treaty of Nanking in 1842: the cession of Hong Kong (Article 3), a six million dollar indemnity (Article 4), and both countries being on an equal footing (Article 11).[45]

Gallery

Page two of the convention

Page two of the convention Page three

Page three Page four, signed by Charles Elliot

Page four, signed by Charles Elliot

Notes

- Hoe & Roebuck 1999, p. xviii

- Morse 1910, p. 628

- Mao 2016, p. 192

- Bernard & Hall 1844, p. 134

- Lowe 1989, p. 12

- Lowe 1989, p. 9

- Le Pichon 2006, pp. 465–466

- The Chinese Repository, vol. 10, p. 63

- "No. 19984". The London Gazette. 3 June 1841. pp. 1423–1424.

- The Chinese Repository, vol. 10, p. 191

- Bingham, vol. 1, p. 271

- Courtauld et al. 1997

- Scott 1842, pp. 5, 9

- Mackenzie 1842, p. 30

- Ellis 1866, p. 148

- The United Service Journal 1841, p. 244

- Mackenzie 1842, p. 31

- Ouchterlony 1844, p. 107

- Eitel 1895, p. 163

- Martin 1841, p. 108

- The Chinese Repository, vol. 12, p. 492

- Waley 1958, p. 132

- Bernard & Hall 1844, p. 135

- Bernard & Hall 1844, p. 137

- Mackenzie 1842, p. 34

- Mackenzie 1842, pp. 35–36

- Bernard & Hall 1844, p. 139

- Hoe & Roebuck 1999, p. 152

- Bernard & Hall 1844, p. 140

- Bernard & Hall 1844, p. 141

- Waley 1958, p. 134

- Mackenzie 1842, pp. 237–253

- Mao 2016, p. 193

- Mao 2016, p. 194

- Bernard & Hall 1844, p. 143

- Ouchterlony 1844, p. 109

- Bingham, vol. 2, p. 47

- The Chinese Repository, vol. 10, p. 233

- The Chinese Repository, vol. 10, p. 184

- Martin 1847, p. 66

- Davis 1852, p. 50

- Davis 1852, pp. 51–52

- Morse 1910, p. 642

- Tsang 2004, p. 12

- Treaty of Nanking

References

- Bernard, William Dallas; Hall, William Hutcheon (1844). Narrative of the Voyages and Services of the Nemesis from 1840 to 1843 (2nd ed.). London: Henry Colburn.

- Bingham, John Elliot (1843). Narrative of the Expedition to China, from the Commencement of the War to Its Termination in 1842 (2nd ed.). Volume 1. London: Henry Colburn.

- Bingham, John Elliot (1843). Narrative of the Expedition to China from the Commencement of the War to Its Termination in 1842 (2nd ed.). Volume 2. London: Henry Colburn.

- The Chinese Repository. Volume 10. Canton. 1841.

- The Chinese Repository. Volume 12. Canton. 1843.

- Courtauld, Caroline; Holdsworth, May; Vickers, Simon (1997). The Hong Kong Story. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-590353-6.

- Davis, John Francis (1852). China, During the War and Since the Peace. Volume 1. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans.

- Eitel, E. J. (1895). Europe in China: The History of Hongkong from the Beginning to the Year 1882. London: Luzac & Company. p. 163.

- Ellis, Louisa, ed. (1886). Memoirs and Services of the Late Lieutenant-General Sir S. B. Ellis, K.C.B., Royal Marines. London: Saunders, Otley, and Co. p. 148

- Hoe, Susanna; Roebuck, Derek (1999). The Taking of Hong Kong: Charles and Clara Elliot in China Waters. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon Press. ISBN 0-7007-1145-7.

- Le Pichon, Alain (2006). China Trade and Empire. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780197263372.

- Lowe, K. J. P. (1989). "Hong Kong, 26 January 1841: Hoisting the Flag Revisited". Journal of the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. Volume 29. p. 12.

- Mao, Haijian (2016). The Qing Empire and the Opium War. Cambridge University Press. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-107-06987-9.

- Mackenzie, Keith Stewart (1842). Narrative of the Second Campaign in China. London: Richard Bentley.

- Martin, Robert Montgomery (1841). "Colonial Intelligence". The Colonial Magazine and Commercial-Maritime Journal. Volume 5. London: Fisher Son, & Co. p. 108.

- Martin, Robert Montgomery (1847). China; Political, Commercial, and Social; In an Official Report to Her Majesty's Government. Volume 2. London: James Madden.

- Morse, Hosea Ballou (1910). The International Relations of the Chinese Empire. Volume 1. New York: Paragon Book Gallery.

- Ouchterlony, John (1844). The Chinese War. London: Saunders and Otley.

- Scott, John Lee (1842). Narrative of a Recent Imprisonment in China After the Wreck of the Kite (2nd ed.). London: W. H. Dalton. pp. 5, 9.

- The United Service Journal and Naval Military Magazine. Part 2. London: Henry Colburn. 1841.

- Tsang, Steve (2004). A Modern History of Hong Kong. London: I.B. Tauris. p. 12. ISBN 1845114191.

- Waley, Arthur (1958). The Opium War Through Chinese Eyes. London: George Allen & Unwin. ISBN 0049510126.