History of Saudi Arabia

The history of Saudi Arabia in its current form as a state began with its foundation in 1744, although the history of the region extends as far as 20,000 years ago. The region has had a global impact twice in world history. In the 7th century it became the cradle of Islam and the capital of the Islamic Rashidun Caliphate. From the mid-20th century the discovery of vast oil deposits propelled it into a key economic and geo-political role.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Saudi Arabia |

|

|

|

At other times, the region existed in relative obscurity and isolation, although from the 7th century the cities of Mecca and Medina had the highest spiritual significance for the Muslim world, with Mecca becoming the destination for the Hajj pilgrimage, an obligation, at least once in a believer's lifetime, if at all possible.[1]

For much of the region's history a patchwork of tribal rulers controlled most of the area. The Al Saud (the Saudi royal family) emerged as minor tribal rulers in Najd in central Arabia. Over the following 150 years, the extent of the Al Saud territory fluctuated. However, between 1902 and 1927, the Al Saud leader, Abdulaziz, carried out a series of wars of conquest which resulted in his establishing the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in 1930.

From 1930 until his death in 1953, Abdulaziz ruled Saudi Arabia as an absolute monarchy. Thereafter six of his sons in succession have reigned over the kingdom:

- Saud, the immediate successor of Abdulaziz, faced opposition from most in the royal family and was eventually deposed.

- Faisal replaced Saud in 1964. Until his murder by a nephew in 1975, Faisal presided over a period of growth and modernization fueled by oil wealth. Saudi Arabia's role in the 1973 oil crisis and, the subsequent rise in the price of oil, dramatically increased the country's political significance and wealth.

- Khalid, Faisal's successor, reigned during the first major signs of dissent: Islamist extremists temporarily seized control of the Grand Mosque in Mecca in 1979.

- Fahd became king in 1982. During his reign Saudi Arabia became the largest oil producer in the world. However, internal tensions increased when the country allied itself with the United States, and others, in the Gulf War of 1991. In the early 2000s, the Islamist opposition to the regime carried out a series of terrorist attacks.

- Abdullah succeeded Fahd in 2005. He instituted a number of mild reforms to modernize many of the country's institutions and, to some extent, increased political participation.

- Salman became king in 2015.

Pre-Islamic Arabia

There is evidence that human habitation in the Arabian Peninsula dates back to about 63,000 years ago.[2][3] Nevertheless, the stone tools from the Middle Paleolithic age along with fossils of other animals discovered at Ti's al Ghadah, in northwestern Saudi Arabia, might imply that hominids migrated through a "Green Arabia" between 300,000 and 500,000 years ago.[4]

Archaeology has revealed some early settled civilizations: the Dilmun civilization on the east of the Arabian Peninsula, Thamud north of the Hejaz, and Kindah kingdom and Al-Magar civilization in the central of Arabian Peninsula. The earliest known events in Arabian history are migrations from the peninsula into neighbouring areas.[5]

There is also evidence from Timna (Israel) and de:Tell el-Kheleifeh (Jordan) that the local Qurayya/Midianite pottery originated within the Hejaz region of NW Saudi Arabia, which suggests that the biblical Midianites originally came from the Hejaz region of NW Saudi Arabia before expanding into Jordan and Southern Israel.[6][7]

The spread of Islam

Muhammad, the Prophet of Islam, was born in Mecca in about 570 and first began preaching in the city in 610, but migrated to Medina in 622. From there, He and His companions united the tribes of Arabia under the banner of Islam and created a single Arab Muslim religious polity in the Arabian Peninsula.

Following Muhammad's death in 632, Abu Bakr became leader of the Muslims as the first Caliph. After putting down a rebellion by the Arab tribes (known as the Ridda wars, or "Wars of Apostasy"), Abu Bakr attacked the Byzantine Empire. On his death in 634, he was succeeded by Umar as caliph, followed by Uthman ibn al-Affan and Ali ibn Abi Talib. The period of these first four caliphs is known as the Rashidun or "rightly guided" Caliphate (al-khulafā' ar-rāshidūn). Under the Rashidun Caliphs, and, from 661, their Umayyad successors, the Arabs rapidly expanded the territory under Muslim control outside of Arabia. In a matter of decades Muslim armies decisively defeated the Byzantine army and destroyed the Persian Empire, conquering huge swathes of territory from the Iberian peninsula to India. The political focus of the Muslim world then shifted to the newly conquered territories.[8][9]

Nevertheless, Mecca and Medina remained the spiritually most important places in the Muslim world. The Quran requires every able-bodied Muslim who can afford it, as one of the five pillars of Islam, to make a pilgrimage, or Hajj, to Mecca during the Islamic month of Dhu al-Hijjah at least once in his or her lifetime.[10] The Masjid al-Haram (the Grand Mosque) in Mecca is the location of the Kaaba, Islam's holiest site, and the Masjid al-Nabawi (the Prophet's Mosque) in Medina is the location of Muhammad tomb; as a result, from the 7th century, Mecca and Medina became the pilgrimage destinations for large numbers of Muslims from across the Muslim world.[11]

Umayyad and Abbasid periods

After the fall of the Umayyad empire in 750 CE, most of what was to become Saudi Arabia reverted to traditional tribal rule soon after the initial Muslim conquests, and remained a shifting patchwork of tribes and tribal emirates and confederations of varying durability.[12][13]

Muawiyah I, the first Umayyad caliph, took an interest in his native Mecca, erecting buildings and digging wells.[14] Under his Marwanids successors, Mecca became the abode of poets and musicians. Even then, Medina eclipsed Mecca in importance for much of the Umayyad period, as it was home to the new Muslim aristocracy.[14] Under Yazid I, the revolt of Abd Allah bin al-Zubair brought Syrian troops to Mecca.[14] An accident led to a fire that destroyed the Kaaba, which was rebuilt by Ibn al-Zubair.[14] In 747, a Kharidjit rebel from Yemen seized Mecca unopposed, but he was soon defeated by Marwan II.[14] In 750, Mecca, along with the rest of the caliphate, was passed to the Abbasids.[14]

Sharifate of Mecca

From the 10th century (and, in fact, until the 20th century) the Hashemite Sharifs of Mecca maintained a state in the most developed part of the region, the Hejaz. Their domain originally comprised only the holy cities of Mecca and Medina but in the 13th century it was extended to include the rest of the Hejaz. Although the Sharifs exercised at most times independent authority in the Hejaz, they were usually subject to the suzerainty of one of the major Islamic empires of the time. In the Middle Ages, these included the Abbasids of Baghdad, and the Fatimids, Ayyubids and Mamluks of Egypt.[12]

Ottoman Era

Beginning with Selim I's acquisition of Medina and Mecca in 1517, the Ottomans, in the 16th century, added to their Empire the Hejaz and Asir regions along the Red Sea and the al-Hasa region on the Persian Gulf coast, these being the most populous parts of what was to become Saudi Arabia. They also laid claim to the interior, although this remained a rather nominal suzerainty. The degree of control over these lands varied over the next four centuries with the fluctuating strength or weakness of the Empire's central authority. In the Hejaz, the Sharifs of Mecca were largely left in control of their territory (although there would often be an Ottoman governor and garrison in Mecca). On the eastern side of the country, the Ottomans lost control of the al-Hasa region to Arab tribes in the 17th century but regained it again in the 19th century. Throughout the period, the interior remained under the rule of a large number of petty tribal rulers in much the same way as it had in previous centuries.[15]

Rise of Wahhabism and the first Saudi state

The emergence of the Saudi dynasty began in central Arabia in 1744. In that year, Muhammad ibn Saud, the tribal ruler of the town of Ad-Dir'iyyah near Riyadh, joined forces with the religious leader Muhammad ibn Abd-al-Wahhab,[16] the founder of the Wahhabi movement.[17] This alliance formed in the 18th century provided the ideological impetus to Saudi expansion and remains the basis of Saudi Arabian dynastic rule today. Over the next 150 years, the fortunes of the Saud family rose and fell several times as Saudi rulers contended with Egypt, the Ottoman Empire, and other Arabian families for control of the peninsula.[3][12]

The first Saudi State was established in 1744 in the area around Riyadh and briefly controlled most of the present-day territory of Saudi Arabia through conquests made between 1786 and 1816; these included Mecca and Medina.[18] Concerned at the growing power of the Saudis, the Ottoman Sultan, Mustafa IV, instructed his viceroy in Egypt, Mohammed Ali Pasha, to reconquer the area. Ali sent his sons Tusun Pasha and Ibrahim Pasha who were eventually successful in routing the Saudi forces in 1818 and destroyed the power of the Al Saud.[3][12]

Return to Ottoman domination

The Al Saud returned to power in 1824 but their area of control was mainly restricted to the Saudi heartland of the Najd region, known as the second Saudi state. However, their rule in Najd was soon contested by new rivals, the Rashidis of Ha'il. Throughout the rest of the 19th century, the Al Saud and the Al Rashid fought for control of the interior of what was to become Saudi Arabia. By 1891, the Al Saud were conclusively defeated by the Al Rashid, who drove the Saudis into exile in Kuwait.[3][12][12][19]

Meanwhile, in the Hejaz, following the defeat of the first Saudi State, the Egyptians continued to occupy the area until 1840. After they left, the Sharifs of Mecca reasserted their authority, albeit with the presence of an Ottoman governor and garrison.[12]

Arab Revolt

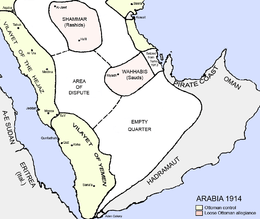

By the early 20th century, the Ottoman Empire continued to control or have suzerainty (albeit nominal) over most of the peninsula. Subject to this suzerainty, Arabia was ruled by a patchwork of tribal rulers (including the Al Saud who had returned from exile in 1902 – see below) with the Sharif of Mecca having preeminence and ruling the Hejaz.[12][15][20]

In 1916, with the encouragement and support of Britain and France[21] (which were fighting the Ottomans in the World War I), the sharif of Mecca, Hussein bin Ali, led a pan-Arab revolt against the Ottoman Empire with the aim of securing Arab independence and creating a single unified Arab state spanning the Arab territories from Aleppo in Syria to Aden in Yemen.

The Arab army comprised bedouin and others from across the peninsula, but not the Al Saud and their allied tribes who did not participate in the revolt partly because of a long-standing rivalry with the Sharifs of Mecca and partly because their priority was to defeat the Al Rashid for control of the interior. Nevertheless, the revolt played a part in the Middle-Eastern Front and tied down thousands of Ottoman troops thereby contributing to the Ottomans' World War I defeat in 1918.[12][22]

However, with the subsequent partitioning of the Ottoman Empire, the British and French reneged on promises to Hussein to support a pan-Arab state. Although Hussein was acknowledged as King of the Hejaz, Britain later shifted support to the Al Saud, leaving him diplomatically and militarily isolated. The revolt, therefore, failed in its objective to create a pan-Arab state but Arabia was freed from Ottoman suzerainty and control.[22]

Unification

In 1902, Abdul-Aziz Al Saud, leader of the Al Saud, returned from exile in Kuwait to resume the conflict with the Al Rashid, and seized Riyadh – the first of a series of conquests ultimately leading to the creation of the modern state of Saudi Arabia in 1930. The main weapon for achieving these conquests was the Ikhwan, the Wahhabist-Bedouin tribal army led by Sultan bin Bajad Al-Otaibi and Faisal al-Duwaish.[19][23][24]

By 1906, Abdulaziz had driven the Al Rashid out of Najd and the Ottomans recognized him as their client in Najd. His next major acquisition was Al-Hasa, which he took from the Ottomans in 1913, bringing him control of the Persian Gulf coast and what would become Saudi Arabia's vast oil reserves. He avoided involvement in the Arab Revolt, having acknowledged Ottoman suzerainty in 1914, and instead continued his struggle with the Al Rashid in northern Arabia. In 1920, the Ikhwan's attention turned to the south-west, when they seized Asir, the region between the Hejaz and Yemen. In the following year, Abdul-Aziz finally defeated the Al Rashid and annexed all northern Arabia.[13][19]

Prior to 1923, Abdulaziz had not risked invading the Hejaz because Hussein bin Ali, King of the Hejaz, was supported by Britain. However, in that year, the British withdrew their support. At a conference in Riyadh in July 1924 complaints were stated against the Hejaz; principally that pilgrimage from Najd was prevented and it boycotted the implementation of certain public policy in contravention of shari'a. Ikhwan units were massed on a large scale for the first time, and under Khalid bin Lu'ayy and Sultan bin Bajad rapidly advanced on Mecca laying waste to symbols of "heathen" practices.[25] The Ikhwan completed their conquest of the Hejaz by the end of 1925. On 10 January 1926 Abdulaziz declared himself King of the Hejaz and, then, on 27 January 1927 he took the title King of Najd (his previous title was Sultan). The use of the Ikhwan to effect the conquest had important consequences for the Hejaz: The old cosmopolitan society was uprooted, and version of Wahhabi culture was imposed as a new compulsory social order.[26]

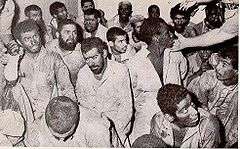

By the Treaty of Jeddah, signed on 20 May 1927, the United Kingdom recognized the independence of Abdul-Aziz's realm (then known as the Kingdom of Hejaz and Najd).[13][19] After the conquest of the Hejaz, the Ikhwan leaders wanted to continue the expansion of the Wahhabist realm into the British protectorates of Transjordan, Iraq and Kuwait. Abdul-Aziz, however, refused to agree to this, recognizing the danger of a direct conflict with the British. The Ikhwan therefore revolted but were defeated in the Battle of Sabilla in 1929, and the Ikhwan leadership were massacred.[27]

In 1930, the two kingdoms of the Hejaz and Najd were united as the 'Kingdom of Saudi Arabia'.[19][23] Boundaries with Transjordan, Iraq, and Kuwait were established by a series of treaties negotiated in the 1920s, with two "neutral zones" created, one with Iraq and the other with Kuwait. The country's southern boundary with Yemen was partially defined by the 1934 Treaty of Ta'if, which ended a brief border war between the two states.[28]

Modern history

Abdulaziz's military and political successes were not mirrored economically until vast reserves of oil were discovered in 1938 in the Al-Hasa region along the Persian Gulf coast. Development began in 1941 and by 1949 production was in full swing.

In February 1945, King Abdul Aziz met President Franklin D. Roosevelt aboard the USS Quincy in the Suez Canal. A historic handshake agreeing on supplying oil to the United States in exchange for guaranteed protection to the Saudi regime is still in force today. It has survived seven Saudi Kings and twelve US presidents.

Abdulaziz died in 1953. King Saud succeeded to the throne on his father's death in 1953. Oil provided Saudi Arabia with economic prosperity and a great deal of political leverage in the international community. At the same time, the government became increasingly wasteful and lavish. Despite the new wealth, extravagant spending led to governmental deficits and foreign borrowing in the 1950s.[13][29][30]

However, by the early 1960s an intense rivalry between the King and his half-brother, Prince Faisal emerged, fueled by doubts in the royal family over Saud's competence. As a consequence, Saud was deposed in favor of Faisal in 1964.[13]

The mid-1960s saw external pressures generated by Saudi-Egyptian differences over Yemen. When civil war broke out in 1962 between Yemeni royalists and republicans, Egyptian forces entered Yemen to support the new republican government, while Saudi Arabia backed the royalists. Tensions subsided only after 1967, when Egypt withdrew its troops from Yemen. Saudi forces did not participate in the Six-Day (Arab–Israeli) War of June 1967, but the government later provided annual subsidies to Egypt, Jordan, and Syria to support their economies.[13][31]

During the 1973 Arab-Israeli war, Saudi Arabia participated in the Arab oil boycott of the United States and Netherlands. A member of the OPEC, Saudi Arabia had joined other member countries in moderate oil price increases beginning in 1971. After the 1973 war, the price of oil rose substantially, dramatically increasing Saudi Arabia's wealth and political influence.[13]

Faisal was assassinated in 1975 by his nephew, Prince Faisal bin Musaid,[32] and was succeeded by his half-brother King Khalid during whose reign economic and social development continued at an extremely rapid rate, revolutionizing the infrastructure and educational system of the country; in foreign policy, close ties with the US were developed.

In 1979, two events occurred which the Al Saud perceived as threatening the regime, and had a long-term influence on Saudi foreign and domestic policy. The first was the Iranian Islamic revolution. There were several anti-government riots in the region in 1979 and 1980. The second event was the seizure of the Grand Mosque in Mecca by Islamist extremists. The militants involved were in part angered by what they considered to be the corruption and un-Islamic nature of the Saudi regime.[13][29][30][33] Part of the response of the royal family was to enforce a much stricter observance of Islamic and traditional Saudi norms. Islamism continued to grow in strength.[13][29][30][33]

King Khalid died in June 1982.[13] Khalid was succeeded by his brother King Fahd in 1982, who maintained Saudi Arabia's foreign policy of close cooperation with the United States and increased purchases of sophisticated military equipment from the United States and Britain.

Following the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990, Saudi Arabia joined the anti-Iraq Coalition. King Fahd, fearing an attack from Iraq, invited soldiers from the US and 32 other countries to Saudi Arabia. Saudi and Coalition forces also repelled Iraqi forces when they breached the Kuwaiti-Saudi border in 1991( see Battle of Khafji).[34]

In 1995, Fahd suffered a debilitating stroke and the Crown Prince, Prince Abdullah assumed day-to-day responsibility for the government. In 2003, Saudi Arabia refused to support the US and its allies in the invasion of Iraq.[13] Terrorist activity within Saudi Arabia increased dramatically in 2003, with the Riyadh compound bombings and other attacks, which prompted the government to take more stringent action against terrorism.[33]

In 2005, King Fahd died and his half-brother, Abdullah, ascended to the throne. Despite growing calls for change, the king has continued the policy of moderate reform.[35] King Abdullah has pursued a policy of limited deregulation, privatization and seeking foreign investment. In December 2005, following 12 years of talks, the World Trade Organization gave the green light to Saudi Arabia's membership.[36]

As the Arab Spring unrest and protests began to spread across Arab world in early 2011, King Abdullah announced an increase in welfare spending. No political reforms were announced as part of the package.[37] At the same time, Saudi troops were sent to participate in the crackdown on unrest in Bahrain. King Abdullah gave asylum to deposed President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali of Tunisia and telephoned President Hosni Mubarak of Egypt (prior to his deposition) to offer his support.[38]

On 23 January 2015, King Abdullah died and was succeeded by King Salman.

See also

References

- "Hajj Explained" in Al Arabia News 03 Oct 2014 by Shounaz Meky

- "Early humans settled in Arabia". usatoday. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- Saudi Embassy (US) Website Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine retrieved 20 January 2011

- Roberts, Patrick; Stewart, Mathew; Alagaili, Abdulaziz N.; Breeze, Paul; Candy, Ian; Drake, Nick; Groucutt, Huw S.; Scerri, Eleanor M. L.; Lee-Thorp, Julia; Louys, Julien; Zalmout, Iyad S.; Al-Mufarreh, Yahya S. A.; Zech, Jana; Alsharekh, Abdullah M.; al Omari, Abdulaziz; Boivin, Nicole; Petraglia, Michael (29 October 2018). "Fossil herbivore stable isotopes reveal middle Pleistocene hominin palaeoenvironment in 'Green Arabia'". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 2 (12): 1871–1878. doi:10.1038/s41559-018-0698-9. hdl:10072/382068. PMID 30374171.

- Philip Khuri Hitti (2002), History of the Arabs, Revised: 10th Edition

- Levy, Thomas E.; Higham, Thomas; Bronk Ramsey, Christopher; Smith, Neil G.; Ben-Yosef, Erez; Robinson, Mark; Münger, Stefan; Knabb, Kyle; Schulze, Jürgen P.; Najjar, Mohammad; Tauxe, Lisa (28 October 2008). "High-precision radiocarbon dating and historical biblical archaeology in southern Jordan". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (43): 16460–16465. doi:10.1073/pnas.0804950105. PMC 2575442. PMID 18955702.

- Bimson, John J.; Tebes, Juan Manuel, Timna revisited : egyptian chronologyand the silver mines of the southernArabah Antiguo Oriente Vol. 7, 2009

- See: Holt (1977a), p.57, Hourani (2003), p.22, Lapidus (2002), p.32, Madelung (1996), p.43, Tabatabaei (1979), p.30–50

- L. Gardet; J. Jomier. "Islam". Encyclopaedia of Islam Online.

- Farah, Caesar (1994). Islam: Beliefs and Observances (5th ed.), pp.145–147 ISBN 978-0-8120-1853-0

- Goldschmidt, Jr., Arthur; Lawrence Davidson (2005). A Concise History of the Middle East (8th ed.), p.48 ISBN 978-0-8133-4275-7

- Encyclopædia Britannica Online: History of Arabia retrieved 18 January 2011

- Joshua Teitelbaum. "Saudi Arabia History". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- M. Th. Houtsma (1993). E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936. BRILL. pp. 441–442. ISBN 978-90-04-09791-9. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- Goodwin, Jason (2003). Lords of the Horizons: A History of the Ottoman Empire. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-42066-6.

- King Abdul Aziz Information Resource – First Ruler of the House of Saud Archived 14 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine retrieved 20 January 2011

- 'Wahhabi', Encyclopædia Britannica Online retrieved 20 January 2011

- The Saud Family and Wahhabi Islam. Library of Congress Country Studies.

- Global Security Retrieved 19 January 2011

- David Murphy, The Arab Revolt 1916–18: Lawrence Sets Arabia Ablaze, Osprey Publishing, 2008,

- Murphy, David The Arab Revolt 1916–1918, London: Osprey, 2008 page 18

- David Murphy, The Arab Revolt 1916–18: Lawrence Sets Arabia Ablaze, Osprey Publishing, 2008

- King Abdul Aziz Information Resource Archived 13 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine retrieved 19 January 2011

- 'Arabian Sands' by Wilfred Thesiger, 1991

- Schulze, Reinhard, A Modern History of the Islamic World (New York: New York University Press, 2002) ("Schulze"), p. 70.

- Schulze, p. 69.

- 'Arabian Sands' by Wilfred Thesiger, 1991, pps 248-249

- Country Data – External boundaries retrieved 19 January 2011

- al-Rasheed, M., A History of Saudi Arabia (Cambridge University Press, 2002) ISBN 0-521-64335-X

- Robert Lacey, The Kingdom: Arabia & The House of Sa'ud, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc, 1981 (Hard Cover) and Avon Books, 1981 (Soft Cover). Library of Congress: 81-83741 ISBN 0-380-61762-5

- "Background note: Saudi Arabia". US State Department. 29 June 2012. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- Robert Lacey, The Kingdom: Arabia and the House of Saud (Harcourt, Brace and Jovanovich Publishing: New York, 1981) p. 426.

- 'Jihad in Saudi Arabia: Violence and Pan-Islamism since 1979' by Thomas Hegghammer, 2010, Cambridge Middle East Studies ISBN 978-0-521-73236-9

- Titus, James (1 September 1996). The Battle of Khafji: An Overview and Preliminary Analysis (Report).

- "Saudi Arabia | The Middle East Channel". Mideast.foreignpolicy.com. Archived from the original on 22 January 2013. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- "Accession status: Saudi Arabia". WTO. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- "Saudi king announces new benefits". Al Jazeera English. 23 February 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- Black, Ian (31 January 2011). "Egypt Protests could spread to other countries". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

Further reading

- Bowen, Wayne H. The History of Saudi Arabia (The Greenwood Histories of the Modern Nations, 2007)

- Determann, Jörg. Historiography in Saudi Arabia: Globalization and the State in the Middle East (2013)

- Kostiner, Joseph. The Making of Saudi Arabia, 1916–1936: From Chieftaincy to Monarchical State (1993)

- Parker, Chad H. Making the Desert Modern: Americans, Arabs, and Oil on the Saudi Frontier, 1933–1973 (U of Massachusetts Press, 2015), 161 pp.

- al-Rasheed, M.. A History of Saudi Arabia (2nd ed. 2010)

- Vassiliev, A. The History of Saudi Arabia (2013)

- Wynbrandt, James and Fawaz A. Gerges. A Brief History of Saudi Arabia (2010)