History of Syria

The history of Syria covers events which occurred on the territory of the present Syrian Arab Republic and events which occurred in the region of Syria. The present Syrian Arab Republic spans territory which was first unified in the 10th century BCE under the Neo-Assyrian Empire, the capital of which was the city of Assur, from which the name "Syria" most likely derives. This territory was then conquered by various rulers, and settled in by different peoples. Syria is considered to have emerged as an independent country for the first time on 24 October 1945, upon the signing of the United Nations Charter by the Syrian government, effectively ending France’s mandate by the League of Nations to "render administrative advice and assistance to the population" of Syria, which came in effect on April 1946. On 21 February 1958, however, Syria merged with Egypt to create the United Arab Republic after plebiscitary ratification of the merger by both countries’ nations, but seceded from it in 1961, thereby recovering its full independence. Since 1963, the Syrian Arab Republic has been ruled by the Ba’ath Party, run by the Assad family exclusively since 1970. Currently Syria is fractured between rival forces due to the Syrian Civil War.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Syria |

|

| Prehistory |

| Bronze Age |

| Antiquity |

| Middle Ages |

|

| Early modern |

| Modern |

|

| Timeline |

|

|

Prehistory

The oldest remains found in Syria date from the Palaeolithic era (c.800,000 BCE). On 23 August 1993 a joint Japan-Syria excavation team discovered fossilized Paleolithic human remains at the Dederiyeh Cave some 400 km north of Damascus. The bones found in this massive cave were those of a Neanderthal child, estimated to have been about two years old, who lived in the Middle Palaeolithic era (ca. 200,000 to 40,000 years ago). Although many Neanderthal bones had been discovered already, this was practically the first time that an almost complete child's skeleton had been found in its original burial state.[1]

Archaeologists have demonstrated that civilization in Syria was one of the most ancient on earth. Syria is part of the Fertile Crescent, and since approximately 10,000 BCE it was one of the centers of Neolithic culture (PPNA) where agriculture and cattle breeding appeared for the first time in the world. The Neolithic period (PPNB) is represented by rectangular houses of the Mureybet culture. In the early Neolithic period, people used vessels made of stone, gyps and burnt lime. Finds of obsidian tools from Anatolia are evidence of early trade relations. The cities of Hamoukar and Emar flourished during the late Neolithic and Bronze Age.

Ancient Near East

The ruins of Ebla, near Idlib in northern Syria, were discovered and excavated in 1975. Ebla appears to have been an East Semitic speaking city-state founded around 3000 BCE. At its zenith, from about 2500 to 2400 BCE, it may have controlled an empire reaching north to Anatolia, east to Mesopotamia and south to Damascus. Ebla traded with the Mesopotamian states of Sumer, Akkad and Assyria, as well as with peoples to the northwest.[2] Gifts from Pharaohs, found during excavations, confirm Ebla's contact with Egypt. Scholars believe the language of Ebla was closely related to the fellow East Semitic Akkadian language of Mesopotamia[3] and to be among the oldest known written languages.[2]

From the third millennium BCE, Syria was occupied and fought over successively by Sumerians, Eblaites, Akkadians, Assyrians, Egyptians, Hittites, Hurrians, Mitanni, Amorites and Babylonians.[2]

Ebla was probably conquered into the Mesopotamian Akkadian Empire (2335-2154 BCE) by Sargon of Akkad around 2330 BCE. The city re-emerged, as the part of the nation of the Northwest Semitic speaking Amorites, a few centuries later, and flourished through the early second millennium BCE until conquered by the Indo-European Hittites.[4] The Sumerians, Akkadians and Assyrians of Mesopotamia referred to the region as Mar.Tu or The land of the Amurru (Amorites) from as early as the 24th century BCE.

Parts of Syria were controlled by the Neo-Sumerian Empire, Old Assyrian Empire and Babylonian Empire between the 22nd and 18th centuries BCE.

The region was fought over by the rival empires of the Hittites, Egyptians, Assyrians and Mitanni between the 15th and 13th centuries BCE, with the Middle Assyrian Empire (1365-1050 BCE) eventually left controlling Syria.

When the Middle Assyrian Empire began to deteriorate in the late 11th century BCE, Canaanites and Phoenicians came to the fore and occupied the coast, and Arameans and Suteans supplanted the Amorites in the interior, as part of the general disruptions and exchanges associated with the Bronze Age Collapse and the Sea Peoples. During this period the bulk of Syria became known as Eber Nari and Aramea.

From the 10th century BCE the Neo-Assyrian Empire (935-605 BCE) arose, and Syria was ruled by Assyria for the next three centuries, until the late 7th century BCE, and was still known as Eber-Nari and Aram throughout the period. It is from this period that the name Syria first emerges, but not in relation to modern Syria, but as an Indo-European corruption of Assyria, which in fact encompassed the modern regions of northern Iraq, north east Syria, south east Turkey and the northwestern fringe of Iran. (see Etymology of Syria)

After this empire finally collapsed, Mesopotamian dominance continued for a time with the short lived Neo-Babylonian Empire (612-539 BCE), which ruled the region for 70 or so years.

Classical antiquity

Persian Syria

In 539 BCE, Cyrus the Great, King of Achaemenid Persians, took Syria as part of his empire. Due to Syria's location on the Eastern Mediterranean coast, its navy fleet, and abundant forests, Persians showed great interest in easing control while governing the region. Thus, the indigenous Phoenicians paid a much lesser annual tribute which was only 350 talent compared to Egypt's tribute of 700 talents. Furthermore, Syrians were allowed to rule their own cities in that they continued to adhere their native religions, establish their own businesses, and build colonies all over the Mediterranean coast. Syria's satraps used to reside in Damascus, Sidon or Tripoli.

In 525 BCE, Cambyses II managed to conquer Egypt after the Battle of Pelusium. Afterwards, he decided to launch an expedition towards Siwa Oasis and Carthage, but his efforts were in vain as Phoenicians refused to operate against their kindred.

Later on, Phoenicians contributed dearly to Xerxes I’s invasion of Greece. Arwad aided the campaign with its fleet, while land troops helped in constructing a bridge for Xerxes's army to cross the Bosphorus into mainland Greece.

During Artaxerxes III’s reign, Sidon, Egyptians, and eleven other Phoenician cities started to revolt against the Persian rulers. The revolutions were heavily suppressed in that Sidon was burnt with its citizens.[5]

Hellenistic Syria

Persian dominion ended with the conquests of the Macedonian Greek king, Alexander the Great in 333-332 BCE after the Battle of Issus which took place south of the ancient town Issus, close to the present-day Turkish town of Iskenderun. Syria was then incorporated into the Seleucid Empire by general Seleucus who started, with the Seleucid Kings after him, using the title of King of Syria. The capital of this Empire (founded in 312 BCE) was situated at Antioch, then a part of historical Syria, but just inside the Turkish border today as well.

A series of six wars, Syrian Wars, were fought between the Seleucid Empire and the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt, during the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE over the region then called Coele-Syria, one of the few avenues into Egypt. These conflicts drained the material and manpower of both parties and led to their eventual destruction and conquest by Rome and Parthia. Mithridates II, King of Parthian Empire, extended his control further west, occupying Dura-Europos in 113 BCE.[6]

By 100 BCE, the once formidable Seleucid Empire encompassed little more than Antioch and some Syrian cities. In 83 BCE, after a bloody strife for the throne of Syria, governed by the Seleucids, the Syrians decided to choose Tigranes the Great, King of Armenia, as the protector of their kingdom and offered him the crown of Syria.[7]

Roman Syria

The Roman general Pompey the Great captured Antioch in 64 BCE, turning Syria into a Roman province and ended Armenian rule,[2] establishing the city of Antioch as its capital.

Antioch was the third largest city in the Roman Empire, after Rome and Alexandria, with an estimated population of 500,000 at its zenith, and being a commercial and cultural hub at the region for many centuries later. The largely Aramaic-speaking population of Syria during the heyday of the empire was probably not exceeded again until the 19th century. Syria's large and prosperous population made it one of the most important Roman provinces, particularly during the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE.[8] In the course of the second century AD, the cities of Palmyra and neighboring Emesa (modern-day Homs) rose to wealth and prominence and both would be notably active in the third century, both in resisting the Parthian Empire but also in raising up Roman usurpers.[9]

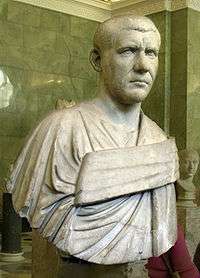

Under the Severan dynasty, Syrian nobles administered Rome and even rose to imperial title, such as the matriarch of the family, Julia Domna, who descended from the Emesan dynasty of priest-kings of Elagabalus and who married Septimius Severus in 187. After the ascension of Domna's two sons to the throne and their eventual death, the Severan dynasty was usurped by Macrinus, a prominent figure in Roman court and a Praetorian prefect. Domna's sister Julia Maesa returned to Emesa, taking her enormous wealth, and her two daughters and grandsons with her.[10] Back in Emesa, her grandson, Elagabalus.[10] Soldiers from Legio III Gallica who were stationed near Emesa would visit the city occasionally,[10] and were persuaded to swear fealty to Elagabalus by Maesa who used her enormous wealth[11] and claimed that he was Caracalla's bastard.[10] Elagabalus later rode to battle against Marcinus, and entered the city of Antioch emerging as emperor, with Marcinus fleeing before being captured near Chalcedon and executed in Cappadocia. Whatsoever, his reign lasted only a short 4 years, filled with sex scandals, eccentricity, decadence, and zealotry. Realizing that the popular support for the emperor was fading, Julia Maesa decided to replace him with her younger grandson, his cousin Severus Alexander, and convinced Elagabalus to name him as his heir and give him the title of Caesar, but after revoking his far more popular cousin of his titles and ranks, and reversing his consulships, the Praetorian guard cheered on Alexander, naming him emperor and slaying Elagabalus and his mother. Severus Alexander's rule was longer, and unlike Elagabalus's disastrous rule, was filled with domestic achievements and he earned the popularity and respect of his people, something Elagabalus never had. He ruled for 13 years, before eventually losing the popularity he once had and being slain by the Legio XXII Primigenia.

Another Emperor of Syrian origin was Philip the Arab, born in modern-day Shahba, he reigned from 244 to 249. His reign enjoyed relative stability, he maintained good relations with the senate, reaffirmed old Roman virtues and traditions, and started many building projects, most popularly in his hometown, renaming it Philippopolis, and raising it to civic status. Whatsoever, the creation of a new city, alongside the massive tribute to the Persians, he had to raise taxes to high levels and stop paying subsidies to the tribes north of the Danube, which were essential to keeping the peace with them. Nonetheless, his reign ended shortly after Decius usurped the throne, killing Philip and emerging as the new emperor.

During the Roman–Sasanian war of the 3rd century, the Romans, struggling in the early stages of the Crisis of the Third Century depended on Odaenathus, the King of the Syrian city-state of Palmyra to secure the Roman East from the Persian invaders and to regain lost Roman territories, so Odaenathus rode north leading the Palmyrene army, and regained Armenia, Northern Syria, parts of Asia Minor from the Persians, and even reached the Persian capital of Ctesiphon, thus weakening the Persians and securing the Roman East, before he was murdered by his own nephew, Maeonius.

Years later, Palmyra rose in rebellion against the Roman Empire under the leadership of Zenobia, Odaenathus's widow and Queen Mother of Palmyra, who led her armies to conquer Syria, Asia Minor, Arabia and Lower Egypt in a series of campaigns in which she annexed almost the entire Roman east, all while the Roman Empire was struggling during the Crisis of the Third Century, ruled by incompetent emperors and torn apart by civil war. Whatsoever, the Palmyrene Empire was short lived; once the Roman general Aurelian rose to power, he rode east, defeated Queen Zenobia in battle twice, and rode to Palmyra to reconquer it and subsequently sacked it around 273 CE, which effectively put an end to Palmyrene civilization.

With the decline of the empire in the west, Syria became part of the Eastern Roman, or Byzantine, Empire in 395. The province was subsequently divided into three, smaller provinces. Syria Prima, with the capital remaining at Antioch, and Syria Secunda, with its capital moving to Apamea on the Orontes, and the new province of Theodorias, with Laodice as its capital.[12] By then the empire had converted to Christianity, in the history of which Syria had played a significant role; Paul the Apostle had converted on the Road to Damascus and emerged as a significant figure in the Church of Antioch, from where he had set off on many of his missionary journeys. (Acts 9:1–43)

Syria remained one of the most important regions of the Byzantine Empire, and was of strategic importance, being occupied by the Sasanians between 609 and 628, then recovered by the emperor Heraclius. Byzantine rule in the region was lost to the Muslims after the battle of Yarmouk and the fall of Antioch.[12]

Medieval era

In 634–640, Syria was conquered by the Muslim Arabs in the form of the Rashidun army led by Khalid ibn al-Walid, resulting in the region becoming part of the Islamic empire. In the mid-7th century, the Umayyad dynasty, then rulers of the empire, placed the capital of the empire in Damascus. Syria was divided into four districts: Damascus, Homs, Palestine and Jordan. The Islamic empire expanded rapidly and at its height stretched from Spain to India and parts of Central Asia; thus Syria prospered economically, being the centre of the empire. Early Umayyad rulers such as Abd al-Malik and Al-Walid I constructed several splendid palaces and mosques throughout Syria, particularly in Damascus, Aleppo and Homs.

There was complete toleration of Christians (mostly ethnic Arameans and in the north east, Assyrians) in this era and several held governmental posts. In the mid-8th century, the Caliphate collapsed amid dynastic struggles, regional revolts and religious disputes. The Umayyad dynasty was overthrown by the Abbasid dynasty in 750, who moved the capital of empire to Baghdad. Arabic — made official under Umayyad rule — became the dominant language, replacing Greek and Aramaic in the Abbasid era. For periods, Syria was ruled from Egypt, under the Tulunids (887–905), and then, after a period of anarchy, the Ikhshidids (941–969). Northern Syria came under the Hamdanids of Aleppo.[13]

.jpg)

The court of Saif al-Daula (944–967) was a center of culture, thanks to its nurturing of Arabic literature. He resisted Byzantine efforts to reconquer Syria by skillful defensive tactics and counter-raids into Anatolia. After his death, the Byzantines captured Antioch and Aleppo (969). Syria was then in turmoil as a battleground between the Hamdanids, Byzantines and Damascus-based Fatimids. The Byzantines had conquered all of Syria by 996, but the chaos continued for much of the 11th century as the Byzantines, Fatimids and Buyids of Baghdad engaged in a struggle for supremacy. Syria was then conquered by the Seljuk Turks (1084–1086), during the reign of Malik-Shah I. Afterward, Nur ad-Din of the Zengid dynasty controlled the region between Aleppo and Damascus in 1154, taken from the Burid dynasty. Later on, Syria was conquered (1175–1185) by Saladin, founder of the Ayyubid dynasty of Egypt.

During the 12th-13th centuries, parts of Syria were held by Crusader states: the County of Edessa (1098–1149), the Principality of Antioch (1098–1268) and County of Tripoli (1109–1289). The area was also threatened by Shi'a extremists known as Assassins (Hassassin) and in 1260 the Mongols briefly swept through Syria. The withdrawal of the main Mongol army prompted the Mamluks of Egypt to invade and conquer Syria. In addition to the sultanate's capital in Cairo, the Mamluk leader, Baibars, made Damascus a provincial capital, with the cities linked by a mail service that traveled by both horses and carrier pigeons. The Mamluks eliminated the last of the Crusader footholds in Syria and repulsed several Mongol invasions.

In 1400, Timur Lenk, or Tamerlane, invaded Syria, defeated the Mamluk army at Aleppo and captured Damascus. Many of the city's inhabitants were massacred, except for the artisans, who were deported to Samarkand.[14][15] At this time the Christian population of Syria suffered persecution.

By the end of the 15th century, the discovery of a sea route from Europe to the Far East ended the need for an overland trade route through Syria. In 1516, the Ottoman Empire conquered Syria.

Ottoman era

_Dervish%2C_Syrian_Peasant%2C_Young_Druse_Woman%2C_Karvass_(Police_Officer)_in_Damascus.jpg)

Ottoman Sultan Selim I conquered most of Syria in 1516 after defeating the Mamlukes at the Battle of Marj Dabiq near Aleppo. Syria was part of the Ottoman Empire from 1516 to 1918, although with 2 brief captures by the Iranian Safavids, notably under Shah Ismail I and Shah Abbas. Ottoman rule was not burdensome to the Syrians because the Turks, as Muslims, respected Arabic as the language of the Koran, and accepted the mantle of defenders of the faith. Damascus became the major entrepot for Mecca, and as such it acquired a holy character to Muslims, because of the barakah (spiritual force or blessing) of the countless pilgrims who passed through on the hadj, the pilgrimage to Mecca.[16]

The Ottoman Turks reorganized Syria into one large province or eyalet. The eyalet was subdivided into several districts or sanjaks. In 1549, Syria was reorganized into two eyalets; the Eyalet of Damascus and the new Eyalet of Aleppo. In 1579, the Eyalet of Tripoli which included Latakia, Hama and Homs was established. In 1586, the Eyalet of Raqqa was established in eastern Syria. Ottoman administration did not foster a peaceful co-existence amongst the different sections of Syrian society but Each religious minority — Shia Muslim, Greek Orthodox, Maronite, Armenian, and Jewish — constituted a millet. The religious heads of each community administered all personal status law and performed certain civil functions as well.[16]

As part of the Tanzimat reforms, an Ottoman law passed in 1864 provided for a standard provincial administration throughout the empire with the Eyalets becoming smaller Vilayets governed by a Wali, or governor, still appointed by the Sultan but with new provincial assemblies participating in administration. The territory of Greater Syria in the final period of Ottoman rule included modern Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Jordan, Palestine, and parts of Turkey and Iraq.

During World War I, French diplomat François Georges-Picot and British diplomat Mark Sykes secretly agreed on the post war division of the Ottoman Empire into respective zones of influence in the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916. In October 1918, Arab and British troops advanced into Syria and captured Damascus and Aleppo. In line with the Sykes-Picot agreement, Syria became a League of Nations mandate under French control in 1920.[17]

The demographics of this area underwent a huge shift in the early part of the 20th century when Ottoman troops along with Kurdish detachments conducted ethnic cleansing of its Christian populations. Some Circassian, Kurdish and Chechens tribes cooperated with the Ottoman authorities in the massacres of Armenian and Assyrian Christians in Upper Mesopotamia, in southeastern Turkey, between 1914 and 1920, with further attacks on unarmed fleeing civilians conducted by local Arab militias.[18][19][20][21][22][23] Many Assyrians fled to northeastern Syria during the Simele Massacre in the early 1930s in Iraq and settled mainly in the Al-Hasakah Governorate governate in the Jazira Region.[19][24][20][25][22][26][27][28] In 1936, the French forces bombarded Amuda (Tusha Amudi). On 13 August 1937, in a revenge attack, about 500 Kurds from the Dakkuri, Milan, and Kiki tribes attacked the then predominantly Christian Amuda,[29] and burned the town.[30] The town was destroyed and the Christian population, about 300 families, fled to the towns of Qamishli and Hasakah.[31] During the great war, Kurdish tribes attacked and sacked and villages in Albaq District immediately to the north of Hakkari mountains. According to lieutenant Ronald Sempill Stafford, a large numbers of Assyrians and Armenians were killed.[20]

In 1941, the Assyrian community of al-Malikiyah was subjected to a vicious assault. Even though the assault failed, Assyrians were terrorized and left in large numbers, and the immigration of Kurds from Turkey to the area have resulted in a Kurdish majority in Amuda, al-Malikiyah, and al-Darbasiyah.[32] The historically-important Christian city of Nusaybin had a similar fate when its Christian population left after it was ceded to Turkey through the Franco-Turkish Agreement of Ankara in October 1921. The Christian population of the city crossed the border into Syria and settled in Qamishli, which was separated by the railway (new border) from Nusaybin. Nusaybin became Kurdish and Qamishli became a Syriac Christian city. Things soon changed, however, with the immigration of Kurds beginning in 1926 following the failure of the rebellion of Saeed Ali Naqshbandi against the Turkish authorities.[32] During the 1920s, waves of Kurds fled their homes in Turkey and settled in northeastern Syria where they were granted citizenship by the French mandate authorities.[33]

Modern history

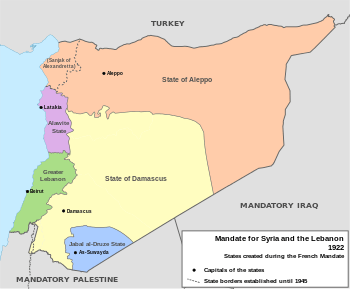

French Mandate

In 1919, a short-lived dependent Kingdom of Syria was established under Emir Faisal I of the Hashemite dynasty, who later became the king of Iraq. In March 1920, the Syrian National Congress proclaimed Faisal as king of Syria "in its natural boundaries" from the Taurus mountains in Turkey to the Sinai desert in Egypt. However, his rule in Syria ended after only a few months following a clash between his Syrian Arab forces and French forces at the Battle of Maysalun. French troops took control of Syria and forced Faisal to flee. Later that year the San Remo conference split up Faisal's kingdom by placing Syria-Lebanon under a French mandate, and Palestine under British control. Syria was divided into three autonomous regions by the French, with separate areas for the Alawis on the coast and the Druze in the south.[34]

Nationalist agitation against French rule led to Sultan al-Atrash leading a revolt that broke out in the Druze Mountain in 1925 and spread across the whole of Syria and parts of Lebanon. The revolt saw fierce battles between rebel and French forces in Damascus, Homs and Hama before it was suppressed in 1927.

The French sentenced Sultan al-Atrash to death, but he had escaped with the rebels to Transjordan and was eventually pardoned. He returned to Syria in 1937 and was met with a huge public reception. Elections were held in 1928 for a constituent assembly, which drafted a constitution for Syria. However, the French High Commissioner rejected the proposals, sparking nationalist protests.

Syria and France negotiated a treaty of independence in September 1936. France agreed to Syrian independence in principle although maintained French military and economic dominance. Hashim al-Atassi, who had been Prime Minister under King Faisal's brief reign, was the first president to be elected under a new constitution, effectively the first incarnation of the modern republic of Syria. However, the treaty never came into force because the French Legislature refused to ratify it. With the fall of France in 1940 during World War II, Syria came under the control of Vichy France until the British and Free French occupied the country in the Syria-Lebanon campaign in July 1941. Syria proclaimed its independence again in 1941, but it was not until 1 January 1944 that it was recognised as an independent republic. There were protests in 1945 over the slow pace of French withdrawal. The French responded to these protests with artillery. In an effort to stop the movement toward independence, French troops occupied the Syrian parliament in May 1945 and cut off Damascus's electricity. Training their guns on Damascus's old city, the French killed 400 Syrians and destroyed hundreds of homes.[35] With casualties mounting Winston Churchill ordered British troops to invade Syria where they escorted French troops to their barracks on June 1. With continuing pressure from the British and Syrian nationalist groups the French were forced to evacuate the last of their troops in April 1946, leaving the country in the hands of a republican government that had been formed during the mandate.[36]

Independence, war and instability

Syria became independent on 17 April 1946. Syrian politics from independence through the late 1960s were marked by upheaval. Between 1946 and 1956, Syria had 20 different cabinets and drafted four separate constitutions.

In 1948, Syria was involved in the Arab–Israeli War, aligning with the other local Arab states who wanted to destroy the state of Israel.[37] The Syrian army entered northern Israel but, after bitter fighting, was gradually driven back to the Golan Heights by the Israelis. An armistice was agreed in July 1949. A demilitarized zone under UN supervision was established; the status of these territories proved a stumbling-block for all future Syrian-Israeli negotiations. It was during this period that many Syrian Jews, who faced growing persecution, fled Syria as part of Jewish exodus from Arab countries.

The outcome of the war was one of factors behind the March 1949 Syrian coup d'état by Col. Husni al-Za'im, in what has been described as the first military overthrow of the Arab World[37] since the Second World War. The coup was caused due to the disgrace the army faced in the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, and thus, sought to relieve itself of that shame. This was soon followed by another coup by Col. Sami al-Hinnawi.[37] Army officer, which was caused by the alienation of Za'im's allies. Adib Shishakli seized power in the third military coup of 1949, in an attempt to prevent a union with Iraq. A Jabal al-Druze uprising was suppressed after extensive fighting (1953–54). Growing discontent eventually led to another coup, in which Shishakli was overthrown in February 1954. The Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party, founded in 1947, played a part in the overthrow of Shishakli. Veteran nationalist Shukri al-Quwatli was president from 1955 until 1958, but by then his post was largely ceremonial.

Power was increasingly concentrated in the military and security establishment, which had proved itself to be the only force capable of seizing and, perhaps, keeping power.[37] Parliamentary institutions remained weak, dominated by competing parties representing the landowning elites and various Sunni urban notables, whilst the economy was mismanaged and little was done to better the role of Syria's peasant majority. In November 1956, as a direct result of the Suez Crisis,[38] Syria signed a pact with the Soviet Union, providing a foothold for Communist influence within the government in exchange for planes, tanks, and other military equipment being sent to Syria.[37] This increase in Syrian military strength worried Turkey, as it seemed feasible that Syria might attempt to retake İskenderun, a matter of dispute between Syria and Turkey. On the other hand, Syria and the Soviet Union accused Turkey of massing its troops on the Syrian border. Only heated debates in the United Nations (of which Syria was an original member) lessened the threat of war.[39]

In this context, the influence of Nasserism, Pan-Arab and anti-imperial ideologies created fertile ground for the idea of closer ties with Egypt.[37][40] The appeal of Egyptian President Gamal Abdal Nasser's leadership in the wake of the Suez Crisis created support in Syria for union with Egypt.[37] On 1 February 1958, Syrian President al-Quwatli and Nasser announced the merging of the two states, creating the United Arab Republic.[36] The union was not a success, however.[37] Discontent with Egyptian dominance of the UAR, led elements opposed to the union under Abd al-Karim al-Nahlawi, to seize power on 28 September 1961. Two days later, Syria re-established itself as the Syrian Arab Republic. Frequent coups, military revolts, civil disorders and bloody riots characterized the 1960s. The 8 March 1963 coup, resulted in installation of the National Council of the Revolutionary Command (NCRC), a group of military and civilian officials who assumed control of all executive and legislative authority. The takeover was engineered by members of the Ba'ath Party led by Michel Aflaq and Salah al-Din al-Bitar. The new cabinet was dominated by Ba'ath members; the moderate al-Bitar became premier.[36][37] He was overthrown early in 1966 by left-wing military dissidents of the party led by General Salah Jadid.

Under Jadid's rule, Syria aligned itself with the Soviet bloc and pursued hardline policies towards Israel[41] and "reactionary" Arab states especially Saudi Arabia, calling for the mobilization of a "people's war" against Zionism rather than inter-Arab military alliances. Domestically, Jadid attempted a socialist transformation of Syrian society at forced pace, creating unrest and economical difficulties. Opponents of the government were harshly suppressed, while the Ba'ath Party replaced parliament as law-making body and other parties were banned. Public support for his government, such as it was, declined sharply following Syria's defeat in the 1967 Six-Day War,[42] when Israel destroyed much of Syria's air force and captured the Golan Heights.[43][44]

Conflicts also arose over different interpretations of the legal status of the Demilitarized Zone. Israel maintained that it had sovereign rights over the zone, allowing the civilian use of farmland. Syria and the UN maintained that no party had sovereign rights over the zone.[45] Israel was accused by Syria of cultivating lands in the Demilitarized Zone, using armored tractors backed by Israel forces. Syria claimed that the situation was the result of an Israeli aim to increase tension so as to justify large-scale aggression, and to expand its occupation of the Demilitarized Zone by liquidating the rights of Arab cultivators.[46] The Israeli defense minister Moshe Dayan said in a 1976 interview that Israel provoked more than 80% of the clashes with Syria.[47][48]

Conflict developed between right-wing army officers and the more moderate civilian wing of the Ba'ath Party. The 1970 retreat of Syrian forces sent to aid the PLO during the "Black September" hostilities with Jordan reflected this political disagreement within the ruling Ba'ath leadership.[49] On 13 November 1970, Minister of Defense Hafez al-Assad seized power in a bloodless military overthrow ("The Corrective Movement").[50]

Syria under Hafez al-Assad (1970–2000)

Upon assuming power, Hafez al-Assad moved quickly to create an organizational infrastructure for his government and to consolidate control. The Provisional Regional Command of Assad's Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party nominated a 173-member legislature, the People's Council, in which the Ba'ath Party took 87 seats. The remaining seats were divided among "popular organizations" and other minor parties. In March 1971, the party held its regional congress and elected a new 21-member Regional Command headed by Assad.

In the same month, a national referendum was held to confirm Assad as President for a 7-year term. In March 1972, to broaden the base of his government, Assad formed the National Progressive Front, a coalition of parties led by the Ba'ath Party, and elections were held to establish local councils in each of Syria's 14 governorates. In March 1973, a new Syrian constitution went into effect followed shortly thereafter by parliamentary elections for the People's Council, the first such elections since 1962.[36] The 1973 Constitution defined Syria as a secular socialist state with Islam recognised as the majority religion.

On 6 October 1973, Syria and Egypt initiated the Yom Kippur War by launching a surprise attack on Israel. After intense fighting, the Syrians were repulsed in the Golan Heights. The Israelis pushed deeper into Syrian territory, beyond the 1967 boundary. As a result, Israel continues to occupy the Golan Heights as part of the Israeli-occupied territories.[51] In 1975, Assad said he would be prepared to make peace with Israel in return for an Israeli withdrawal from "all occupied Arab land".

In 1976, the Syrian army intervened in the Lebanese civil war to ensure that the status quo was maintained, and the Maronite Christians remained in power. This was the beginning of what turned out to be a thirty-year Syrian military occupation. Many crimes in Lebanon, including the accused assassinations of Rafik Hariri, Kamal Jumblat and Bachir Gemayel were attributed to the Syrian forces and intelligence services although were not proven to this day.[52] In 1981 Israel declared its annexation of the Golan Heights. The following year, Israel invaded Lebanon and attacked the Syrian army, forcing it to withdraw from several areas. When Lebanon and Israel announced the end of hostilities in 1983, Syrian forces remained in Lebanon. Through extensive use of proxy militias, Syria attempted to stop Israel from taking over southern Lebanon. Assad sent troops into Lebanon for a second time in 1987 to enforce a ceasefire in Beirut.

The Syrian-sponsored Taif Agreement finally brought the Lebanese civil war to an end in 1990. However, the Syrian Army's presence in Lebanon continued until 2005, exerting a strong influence over Lebanese politics. The assassination of the popular former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri, was blamed on Syria, and pressure was put on Syria to withdraw their forces from Lebanon. On 26 April 2005 the bulk of the Syrian forces withdrew from Lebanon[53] although some of its intelligence operatives remained, drawing further international rebuke.[54]

About one million Syrian workers went to Lebanon after the war to find jobs in the reconstruction of the country.[55] In 1994 the Lebanese government controversially granted citizenship to over 200,000 Syrian residents in the country.[56] (For more on these issues, see Demographics of Lebanon)

The government was not without its critics, though open dissent was repressed. A serious challenge arose in the late 1970s, however, from fundamentalist Sunni Muslims, who rejected the secular values of the Ba'ath program and objected to rule by the Shia Alawis. After the Islamic Revolution in Iran, Muslim groups instigated uprisings and riots in Aleppo, Homs and Hama and attempted to assassinate Assad in 1980. In response, Assad began to stress Syria's adherence to Islam. At the start of Iran–Iraq War, in September 1980, Syria supported Iran, in keeping with the traditional rivalry between Ba'athist leaderships in Iraq and Syria. The arch-conservative Muslim Brotherhood, centered in the city of Hama, was finally crushed in February 1982 when parts of the city were hit by artillery fire and leaving between 10,000 and 25,000 people, mostly civilians, dead or wounded (see Hama massacre).[57] The government's actions at Hama have been described as possibly being "the single deadliest act by any Arab government against its own people in the modern Middle East".[58] Since then, public manifestations of anti-government activity have been limited.[36] Amidst the pressure of the time, Hafez al-Assad also cracked down on secular and liberal dissent, jailing and torturing prominent Syrian figures like lawyer and former judge Haitham al-Maleh, political leader Riad al-Turk, writer Akram al-Bunni, and poet Mohammed al-Maghout.[59]

When Iraq invaded Kuwait in 1990, Syria joined the US-led coalition against Iraq. This led to improved relations with the US and other Arab states. Syria participated in the multilateral Southwest Asia Peace Conference in Madrid in October 1991, and during the 1990s engaged in direct negotiations with Israel. These negotiations failed over the Golan Heights issue and there have been no further direct Syrian–Israeli talks since President Hafez al-Assad's meeting with then President Bill Clinton in Geneva in March 2000.[60]

In 1994, Assad's son Bassel al-Assad, who was likely to succeed his father, was killed in a car accident. Assad's brother, Rifaat al-Assad, was "relieved of his post" as vice-president in 1998. Thus, when Assad died in 2000, his second son, Bashar al-Assad was chosen as his successor.

Syria under Bashar al-Assad (2000–present)

Hafez al-Assad died on 10 June 2000, after 30 years in power. Immediately following al-Assad's death, the Syrian Parliament amended the constitution, reducing the mandatory minimum age of the President from 40 to 34. This allowed Bashar Assad to become eligible for nomination by the ruling Ba'ath party. On 10 July 2000, Bashar al-Assad was elected President by referendum in which he ran unopposed, garnering 97.29% of the vote, according to Syrian Government statistics.[36]

The period after Bashar al-Assad's election in the summer of 2000 saw new hopes of reform and was dubbed the Damascus Spring. The period was characterized by the emergence of numerous political forums or salons where groups of like-minded people met in private houses to debate political and social issues. The phenomenon of salons spread rapidly in Damascus and to a lesser extent in other cities. Political activists, such as Riad Seif, Haitham al-Maleh, Kamal al-Labwani, Riyad al-Turk, and Aref Dalila were important in mobilizing the movement.[61] The most famous of the forums were the Riad Seif Forum and the Jamal al-Atassi Forum. Pro-democracy activists mobilized around a number of political demands, expressed in the "Manifesto of the 99". Assad ordered the release of some 600 political prisoners in November 2000. The outlawed Muslim Brotherhood resumed its political activity. In May 2001 Pope John Paul II paid a historic visit to Syria.

However, by the autumn of 2001, the authorities had suppressed the pro-reform movement, crushing hopes of a break with the authoritarian past of Hafez al-Assad. Arrests of leading intellectuals continued, punctuated by occasional amnesties, over the following decade. Although the Damascus Spring had lasted for a short period, its effects still echo during the political, cultural and intellectual debates in Syria today.[62]

Tensions with the USA grew worse after 2002, when the US claimed Damascus was acquiring weapons of mass destruction and included Syria in a list of states that they said made-up an "axis of evil". The USA was critical of Syria because of its strong relationships with Hamas, the Islamic Jihad Movement in Palestine and Hezbollah, which the US, Israel and EU regard as terrorist groups. In 2003 the US threatened sanctions if Damascus failed to make what Washington called the "right decisions". Syria denied US allegations that it was developing chemical weapons and helping fugitive Iraqis. An Israeli air strike against a Palestinian militant camp near Damascus in October 2003 was described by Syria as "military aggression".[63] President Assad visited Turkey in January 2004, the first Syrian leader to do so. The trip marked the end of decades of frosty relations, although ties were to sour again after 2011. In May 2004, the USA imposed economic sanctions on Syria over what it called its support for terrorism and failure to stop militants entering Iraq.[64] Tensions with the US escalated in early 2005 after the killing of the former Lebanese PM Hariri in Beirut. Washington cited Syrian influence in Lebanon behind the assassination. Damascus was urged to withdraw its forces from Lebanon, which it did by April.[65]

Following 2004 al-Qamishli riots, the Syrian Kurds protested in Brussels, in Geneva, in Germany, at the US and UK embassies, and in Turkey. The protesters pledged against violence in north-east Syria starting Friday, 12 March 2004, and reportedly extending over the weekend resulting in several deaths, according to reports. The Kurds allege the Syrian government encouraged and armed the attackers. Signs of rioting were seen in the towns of Qameshli and Hassakeh.[66]

Renewed opposition activity occurred in October 2005 when activist Michel Kilo and other opposition figures launched the Damascus Declaration, which criticized the Syrian government as "authoritarian, totalitarian and cliquish" and called for democratic reform.[67] Leading dissidents Kamal al-Labwani and Michel Kilo were sentenced to a long jail terms in 2007, only weeks after human rights lawyer Anwar al-Bunni was jailed. Although Bashar al-Assad said he would reform, the reforms have been limited to some market reforms.[57][68][69]

Over the years the authorities have tightened Internet censorship with laws such as forcing Internet cafes to record all the comments users post on chat forums.[70] While the authorities have relaxed rules so that radio channels can now play Western pop music, websites such as Wikipedia, YouTube, Facebook and Amazon have been blocked,[71] but were recently unblocked throughout the nation.[72][73]

Syria's international relations improved for a period. Diplomatic relations with Iraq were restored in 2006, after nearly a quarter century. In March 2007, dialogue between Syria and the European Union was relaunched. The following month saw US House of Representatives Speaker Nancy Pelosi meet President Assad in Damascus, although President Bush objected.[74][75][76][77] Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice then met with Syrian Foreign Minister Walid Muallem in Egypt, in the first contact at this level for two years.[78][79][80]

An Israeli air strike against a site in northern Syria in September 2007 was a setback to improving relations. The Israelis claimed the site was a nuclear facility under construction with North Korean help.[81] 2008 March - When Syria hosted an Arab League summit in 2008, many Western states sent low-level delegations in protest at Syria's stance on Lebanon. However, the diplomatic thaw was resumed when President Assad met the then French President Nicolas Sarkozy in Paris in July 2008. The visit signaled the end of Syria's diplomatic isolation by the West that followed the assassination of Hariri in 2005. While in Paris, President Assad also met the recently elected Lebanese president, Michel Suleiman. The two men laid the foundations for establishing full diplomatic relations between their countries. Later in the year, Damascus hosted a four-way summit between Syria, France, Turkey and Qatar, in a bid to boost efforts towards Middle East peace.

In April 2008, President Assad told a Qatari newspaper that Syria and Israel had been discussing a peace treaty for a year, with Turkey acting as a mediator. This was confirmed in May 2008 by a spokesman for Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert. The status of the Golan Heights, a major obstacle to a peace treaty, was being discussed.[82]

In 2008, an explosion killed 17 on the outskirts of Damascus, the most deadly attack in Syria in several years. The government blamed Islamist militants.[83][84][85]

2009 saw a number of high level meetings between Syrian and US government diplomats and officials. US special envoy George J. Mitchell visited for talks with President Assad on Middle East peace.[86][87][88][89] Trading launched on Syria's stock exchange in a gesture towards liberalising the state-controlled economy.[90][91][92] The Syrian writer and pro-democracy campaigner Michel Kilo was released from prison after serving a three-year sentence.[93][94] In 2010, the USA posted its first ambassador to Syria after a five-year break.[95][96][97]

The thaw in diplomatic relations came to an abrupt end. In May 2010, the USA renewed sanctions against Syria, saying that it supported terrorist groups, seeks weapons of mass destruction and has provided Lebanon's Hezbollah with Scud missiles in violation of UN resolutions.[98][99][100] In 2011 the UN's IAEA nuclear watchdog reported Syria to the UN Security Council over its alleged covert nuclear programme.[101][102]

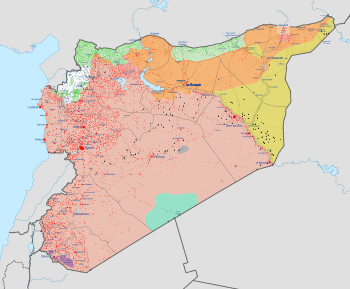

Civil War (2011–present)

(For a more detailed, interactive map, see Template:Syrian Civil War detailed map.)

.svg.png)

The Syrian Uprising (later known as the Syrian Civil War) is an ongoing internal conflict between the Syrian army and the rebel groups composed by many heterogeneous branches. Encouraged by the Arab Spring, there were pro-reform protests in Damascus and the southern city of Deraa in March 2011. Protestors demanded political freedom and the release of political prisoners. This was immediately followed by a government crackdown whereby the Syrian Army was deployed to quell unrest.[106][107]

Security forces shot and killed a number of people in Deraa, triggering days of violent unrest that steadily spread nationwide over the following months. There were unconfirmed reports that soldiers who refused to open fire on civilians were summarily executed.[108] The Syrian government denied reports of executions and defections, and blamed militant armed groups for causing trouble.[109] President Assad announced some conciliatory measures: dozens of political prisoners were released, he dismissed the government, and in April he lifted the 48-year-old state of emergency. The government accused protesters of being stirred up by Israeli agents, and in May, army tanks entered Deraa, Banyas, Homs and the suburbs of Damascus in an effort to crush anti-government protests. In June, the government claimed that in 120 members of the security forces had been killed by "armed gangs" in the northwestern town of Jisr al-Shughour. Troops besieged the town, whose inhabitants mostly fled to Turkey. At the same time, President Assad pledged to start a "national dialogue" on reform. He sacked the governor of the northern province of Hama and sent in more troops to restore order.

In July 2011, some of the anti-Assad groups met in Istanbul with a view to bringing the various internal and external opposition groups together. They agreed to form the Syrian National Council. Rebel fighters were joined by army defectors on the Turkish–Syrian border and declared the formation of the Free Syrian Army (FSA). They began forming fighting units to escalate the insurgency from September 2011. From the outset, the FSA was a disparate collection of loosely organized and largely independent units.

In December 2011, Syria agreed to an Arab League initiative allowing Arab observers into the country. Thousand of people gathered in Homs to greet them, but the League suspended the mission in January 2012, citing worsening violence. Twin suicide bomb attacks outside security buildings in Damascus killed 44 people in December 2011. This was the first in a series of bombings and suicide attacks in the Syrian capital that continued throughout 2012. The opposition accuses the government itself of staging the attacks. The government accuses the Western media of turning a blind eye to the rebels' use of al-Qaeda-style terrorist attacks.

As the Syrian army recaptured the Homs district of Baba Amr in March 2012, the UN Security Council endorsed a non-binding peace plan drafted by UN envoy Kofi Annan. However, the violence continued unabated. A number of Western nations expelled senior Syrian diplomats in protest. In May, the UN Security Council strongly condemned both the Syrian government's use of heavy weaponry and the massacre by rebels of over a hundred civilians in Houla, near Homs.

The UN reported that, in the first six months alone, 9,100–11,000 people had been killed during the insurgency, of which 2,470–3,500 were actual combatants and rest were civilians.[110][111][112] The Syrian government estimated that more than 3,000 civilians, 2,000–2,500 members of the security forces and over 800 rebels had been killed.[113] UN observers estimated that the death toll in the first six months included over 400 children.[114][115][116][117][118] Additionally, some media reported that over 600 political prisoners and detainees, some of them children, have died in custody.[119] A prominent case was that of Hamza Al-Khateeb. Syria's government has disputed Western and UN casualty estimates, characterizing their claims as being based on false reports originating from rebel groups.[120]

According to the UN, about 1.2 million Syrians had been internally displaced within the country[121] and over 355,000 Syrian refugees had fled to the neighboring countries of Jordan,[122] Iraq,[123] Lebanon and Turkey during the first year of fighting.[121][124]

Both sides have been accused of human rights abuses. The United Nations Human Rights Council has found numerous incidents of torture, summary executions and attacks on cultural property. The Syrian government has been accused of committing the majority of war crimes, although independent verification has proven extremely difficult.[125] The conflict has the hallmarks of a sectarian civil war; the leading government figures are Shia Alawites, whilst the rebels are mainly Sunni Muslims. Although neither side in the conflict has described sectarianism as playing a major role,[126] the UN Human Rights Council has warned that "entire communities are at risk of being forced out of the country or of being killed."[127] The conflict has increasingly forced minorities to align themselves with one side or another, with Christians, Druze and Armenians largely siding with the government while Turkmen are mostly anti-government. Palestinians have split, while Kurds have fought against both rebels and government forces. Some Christian communities have formed militias to protect their neighborhoods from rebel fighters. International religious freedom groups have been drawing attention to the plight of Syria's Christian minority at the hands of the rebel jihadist elements. Churches have been destroyed, killings and kidnapping reported, and Christians driven out of their homes. Almost the entire Christian population of Homs—50,000–60,000 people—have fled the city.[128]

The Arab League, the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, GCC states, the US and the European Union have condemned the use of violence by the Syrian government and applied sanctions against Syria. China and Russia have sought to avoid foreign intervention and called for a negotiated settlement. They have avoided condemning the Syrian government and disagree with sanctions. China has sought to engage with the Syrian opposition.[129] The Arab League and Organisation of Islamic Cooperation have both suspended Syria's membership.[130][131]

In June 2012 a number of high-ranking military and political personnel, such as Manaf Tlas[132] and Nawaf al-Fares, fled the country. Nawaf al-Fares stated in a video that this was in response to crimes against humanity by the Assad government.[133] In August 2012, the country's Deputy Prime Minister Qadri Jamil said President Assad's resignation could not be a condition for starting peace negotiations.[134]

Syria-Turkish tension increased in October 2012, when Syrian mortar fire hit a Turkish border town and killed five civilians. Turkey returned fire and intercepted a Syrian plane allegedly carrying arms from Russia. Both countries banned each other's planes from their air space. In the south, the Israeli military fired on Syrian units after alleging shelling from Syrian positions across the Golan Heights.

After heavy fighting, a fire destroyed much of the historic market of Aleppo in October. A UN-brokered ceasefire during the Islamic holiday of Eid al-Adha soon broke down as fighting and bomb attacks continued in several cities. By this time, the Syrian Arab Red Crescent estimated that 2.5 million people had been displaced within Syria, double the previous estimate. According to the anti-Assad Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, almost 44,000 people have died since the insurgency against began. According to a UN report, the humanitarian situation has been "aggravated by widespread destruction and razing of residential areas. ... Towns and villages across Latakia, Idlib, Hama and Dara'a governorates have been effectively emptied of their populations," the report said. "Entire neighborhoods in southern and eastern Damascus, Deir al-Zour and Aleppo have been razed. The downtown of Homs city has been devastated."[127]

In November 2012, the National Coalition for Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces, commonly named the 'Syrian National Coalition' was formed at a meeting hosted by Qatar. Islamist militias in Aleppo, including the Al-Nusra and Al-Tawhid groups, refused to join the Coalition, denouncing it as a "conspiracy". There is also concern over Muslim Brotherhood or Islamist domination of the anti-Assad coalition.[128] Despite this, in December 2012, the US, the Arab states of the Persian Gulf, Turkey and many EU members moved quickly to recognise the coalition as the "sole legitimate representative of the Syrian people" rather than the former main rebel group, the Syrian National Council. The USA and Persian Gulf states wanted a reshaped opposition coalition to include more Syrians who were fighting on the ground—as opposed to those who had been in exile for decades—and one that was more broadly representative of all Syria's regions. At the same times, the U.S. has added al-Nusra—one of the most successful rebel military groups—to its terrorist list, citing ties to al-Qaeda.

On 20 December 2012, a UN Independent Commission of Inquiry said that Syria's newest insurgent groups increasingly operate independently of the rebel command and some are affiliated with al-Qaeda. Many of the insurgents are foreign fighters; "Sunnis hailing from countries in the Middle East and North Africa," and are linked to extremist groups.[127]

A sarin gas attack occurred in Syria, near Damascus, on 21 August 2013. The attack is alleged to have been carried out by the Syrian government of Bashar al-Assad according to French and United States' government's intelligence.[135][136][137] However, Russia, one of the Syrian government's international supporters, seems unconvinced of the origins of the attack.[138] The attack has led to increased international pressure on the Assad government and threat of international military intervention in Syria led by United States armed forces.

On 22 December 2016, the city of Aleppo was fully captured by the Syrian Arab Army forces.

See also

- Abila

- Adib Shishakli

- Bilad al-Sham

- Franco-Syrian Treaty of Independence (1936)

- Hashim al-Atassi

- History of the Levant

- History of Asia

- History of Damascus

- History of the Middle East

- List of Presidents of Syria

- List of Prime Ministers of Syria

- Munir al-Ajlani

- Ottoman Syria

- Rulers of Damascus

- Politics of Syria

- Shukri al-Quwatli

- Syria

- Syrian Social Nationalist Party

- Taj al-Din al-Hasani

- Timeline of Syrian history

- Timeline of Damascus

- Usamah ibn Munqidh

- Kitab al-I'tibar Autobiography of Usamah

References

- "The Dederiyeh Neanderthal". www.kochi-tech.ac.jp.

- "Syria: A country Study – Ancient Syria". Library of Congress. 2007. Retrieved 5 September 2007.

- "The Aramaic Language and Its Classification" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 14 (1).

- Relations between God and Man in the Hurro-Hittite Song of Release, Mary R. Bachvarova, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Jan–Mar SAAD 2005

- Bounni, Adnan. "Achaemenid: Persian Syria 538-331 BCE. Two Centuries of Persian Rule". Iran Chamber Society. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- Curtis 2007, pp. 11–12

- Manaseryan, Ruben (1985). "Տիգրան Բ [Tigran II]". Armenian Soviet Encyclopedia (in Armenian). 11. Yerevan: Armenian Encyclopedia Publishing. pp. 697–698.

- Cavendish Corporation, Marshall (2006). World and Its Peoples. Marshall Cavendish. p. 183. ISBN 0-7614-7571-0.

- Young, Gary K. "Emesa in Roman Syria". Prudentia: 43.

- Gibbon, Edward (1776). The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. p. 182.

- "Roman Emperors - DIR severan Julias". www.roman-emperors.org.

- Kazhdan, Alexander (Ed.) (1991). Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford University Press. p. 1999. ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Syria: History Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 22 October 2008.

- Battle of Aleppo.

- "The Eastern Mediterranean, 1400–1600 CE". Metmuseum.org. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- "Syria – Ottoman Empire". Library of Congress Country Studies.

- Mandat Syrie-Liban. Retrieved 1 February 2010.

- Travis, Hannibal. Genocide in the Middle East: The Ottoman Empire, Iraq, and Sudan. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 2010, 2007, pp. 237–77, 293–294.

- Hovannisian, Richard G., 2007. [The Armenian Genocide: Cultural and Ethical Legacies https://books.google.com/books?id=K3monyE4CVQC&pg=PA271&dq=assyrian+genocide+by+kurds+in+syria&hl=en#v=onepage&q=Amuda&f=false]. Accessed on 11 November 2014.

- R. S. Stafford (2006). The Tragedy of the Assyrians. pp. 24–25.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (2007). The Armenian Genocide: Cultural and Ethical Legacies. Archived from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- Joan A. Argenter, R. McKenna Brown (2004). On the Margins of Nations: Endangered Languages and Linguistic Rights. p. 199.

- Lazar, David William, not dated A brief history of the plight of the Christian Assyrians* in modern-day Iraq Archived 17 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine. American Mespopotamian.

- R. S. Stafford (2006). The Tragedy of the Assyrians. p. 24.

- R. S. Stafford (2006). The Tragedy of the Assyrians. pp. 24–25.

- "Ray J. Mouawad, Syria and Iraq – Repression Disappearing Christians of the Middle East". Middle East Forum. 2001. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- Bat Yeʼor (2002). Islam and Dhimmitude: Where Civilizations Collide. p. 162.

- Lazar, David William, not dated.A brief history of the plight of the Christian Assyrians* in modern-day Iraq Archived 17 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine. American Mespopotamian.

- Jordi Tejel, "Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society", footnote 57.

- Watenpaugh, Keith David (2014). Being Modern in the Middle East: Revolution, Nationalism, Colonialism, and the Arab Middle Class. Princeton University Press. p. 270. ISBN 1-4008-6666-9.

- John Joseph, "Muslim-Christian Relations and Inter-Christian Rivalries in the Middle East", p107.

- Abu Fakhr, Saqr, 2013. As-Safir daily Newspaper, Beirut. in Arabic Christian Decline in the Middle East: A Historical View

- Chatty, Dawn, 2010. Displacement and Dispossession in the Modern Middle East. Cambridge University Press. pp. 230-232.

- Peter N. Stearns, William Leonard Langer (2001). "The Middle East, p. 761". The Encyclopedia of World History. Houghton Mifflin Books. ISBN 978-0-395-65237-4.

- Rogan, Eugene (2011). The Arabs: A Complete History. Penguin. pp. 244–246.

- "Background Note: Syria". United States Department of State, Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs, May 2007.

- "Syria: World War II and independence". Britannica Online Encyclopedia.

- Robson, John. (2012-02-10) Syria hasn't changed, but the world has. Toronto Sun. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- Brecher, Michael; Jonathan Wilkenfeld (1997). A Study of Crisis. University of Michigan Press. pp. 345–346. ISBN 0-472-10806-9.

- Walt, Stephen (1990). The Origins of Alliances. Cornell University Press. pp. 72–73. ISBN 0-8014-9418-4.

- "Yearbook of the United Nations 1966 (excerpts) (31 December 1966)". unispal.un.org.

- Mark A. Tessler (1994). A History of the Israeli–Palestinian Conflict. Indiana University Press. p. 382. ISBN 978-0-253-20873-6. Retrieved 29 December 2010.

- Oren, Michael. (2006). "The Six-Day War", in Bar-On, Mordechai (ed.), Never-Ending Conflict: Israeli Military History. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-275-98158-4, p. 135.

- Gilbert, Martin. (2008). Israel – A History. McNally & Loftin Publishers. ISBN 0-688-12363-5, p. 365.

- Alasdair Drysdale, Raymond A. Hinnebusch (1991), "Syria and the Middle East peace process", Council on Foreign Relations, ISBN 0-87609-105-2, p. 99.

- "OpenDocument Yearbook of the United Nations 1967". Archived from the original on 6 December 2013.

- General's Words Shed a New Light on the Golan By Serge Schmemann, 11 May 1997. Retrieved 1 February 2010.

- Eyal Zisser (2002). "June 1967: Israel's Capture of the Golan Heights". Israel Studies. 7 (1): 168–194. doi:10.2979/isr.2002.7.1.168.

- "Jordan asked Nixon to attack Syria, declassified papers show - CNN.com". Edition.cnn.com. 28 November 2007. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- Seale, Patrick (1988). Asad: The Struggle for the Middle East. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-06976-5.

- Rabinovich, Abraham (2005). The Yom Kippur War: The Epic Encounter That Transformed the Middle East. New York, New York: Schocken Books. p. 302. ISBN 0-8052-4176-0.

- Anti Syrian leader warns of more Lebanon killings The Epoch Times, 22 November 2006.

- "Security Council Press Release SC/8372". Un.org. 29 April 2005. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- Syrian intelligence still in Lebanon Washington Post, 27 April 2005.

- "Syria's Role in Lebanon by Mona Yacoubian: USIPeace Briefing: U.S. Institute of Peace". Usip.org. Archived from the original on 18 July 2008. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- "تقرير الوزير اللبناني أحمد فتفت عن ملف المجنسين". Alzaytouna.net. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- Ghadry, Farid N. (Winter 2005). "Syrian Reform: What Lies Beneath". The Middle East Quarterly.

- Wright, Robin, Dreams and Shadows: the Future of the Middle East, Penguin Press, 2008, pp. 243–4.

- Oweis, Khaled. "Fear barrier crumbles in Syrian "kingdom of silence"". Reuters. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- Marc Perelman (11 July 2003). "Syria Makes Overture Over Negotiations - Forward.com". Forward.com. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- "Syria Smothering Freedom of Expression: the detention of peaceful critics". Amnesty International. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- George, Alan (2003). Syria: neither bread nor freedom. London: Zed Books. pp. 56–58. ISBN 1-84277-213-9.

- Huggler, Justin (6 October 2003). "Israel launches strikes on Syria in retaliation for bomb attack". London: The Independent. Retrieved 23 October 2008.

- Fact Sheet, The White House. (11 May 2004)

- Guerin, Orla (6 March 2005). "Syria sidesteps Lebanon demands". BBC News. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- "Naharnet Newsdesk – Syria Curbs Kurdish Riots for a Merger with Iraq's Kurdistan". Naharnet.com. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- "The Damascus Declaration for Democratic National Change". 15 October 2005. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- Michael Bröning (7 March 2011). "The Sturdy House That Assad Built". The Foreign Affairs.

- "Profile: Syria's Bashar al-Assad". BBC News. 10 March 2005. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- "Bashar Al-Assad, President, Syria". Reporters Without Borders. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- "Red lines that cannot be crossed – The authorities don't want you to read or see too much". The Economist. 24 July 2008.

- Weber, Harrison (8 February 2011). "Facebook and YouTube Unblocked in Syria Today". The Next Web. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- "Facebook, YouTube unblocked in Syria". ITP.net. 9 February 2011. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- Shadid, Anthony (5 April 2007). "Pelosi Meets Syrian President Despite Objections From Bush". Washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- "House Speaker Pelosi Says Syria Willing to Resume Peace Talks With Israel". Fox News. 4 April 2007. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- Associated, The (5 April 2007). "U.S. Republican meets Assad day after contentious Pelosi visit". Haaretz. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- "Pelosi meets with Syria's Assad". NBC News. 4 April 2007. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- "Condi Rice never looks back". Salon.com. 4 May 2007. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- "Rice meets with Syrian FM in Egypt's resort". Xinhua. 4 May 2007. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- "Middle East | US and Syria hold landmark talks". BBC News. 3 May 2007. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- Sanger, David (14 October 2007). "Israel Struck Syrian Nuclear Project, Analysts Say". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- Walker, Peter; News Agencies (21 May 2008). "Olmert confirms peace talks with Syria". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

Israel and Syria are holding indirect peace talks, with Turkey acting as a mediator....

- Mitchell Prothero in Beirut and Peter Beaumont (28 September 2008). "Syria: Damascus car bomb kills 17 at Shia shrine". London: Guardian. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- Makdessi, Marwan (27 September 2008). "Car bomb near Syrian security base kills 17". Reuters. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- "Syria: Car bomb kills 17 in Damascus". CNN.com. 27 September 2008. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- Otterman, Sharon (29 July 2009). "U.S. Opens Way to Ease Sanctions Against Syria". The New York Times.

- Associated Press (26 July 2009). "Barack Obama's Middle East envoy steps up diplomatic push in Syria". London: Guardian. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- "Visit to Syria starts week of U.S. diplomacy in Middle East". CNN.com. 27 July 2009. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- "Mitchell Cites Syria's Role in Mideast Peace Effort". The New York Times. 14 June 2009.

- Raed Rafei (11 March 2009). "Syria launches stock exchange". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- Whatley, Stuart (10 March 2009). "Syria Launches Damascus Securities Exchange As Part Of Economic Liberalization Effort". Huffingtonpost.com. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- "Syria launches first stock exchange". Alarabiya.net. 10 March 2009. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- Labidi, Kamel. "Q&A: Syrian journalist Michel Kilo after prison". Committee to Protect Journalists. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- "Michel Kilo released". Newsfromsyria.com. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- Sweet, Lynn (16 February 2010). "Obama names ambassador to Syria; first in five years". Blogs.suntimes.com. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- "BBC News - Robert Ford is first US ambassador to Syria since 2005". Bbc.co.uk. 16 January 2011. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- "US appoints first ambassador to Syria for five years". DW.DE. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- "Obama renews Syria sanctions". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- "Barack Obama renews sanctions on Syria for a year". London: Telegraph. 4 May 2010. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- France-Presse, Agence (3 May 2010). "Obama Renews Syria Sanctions". The New York Times.

- Jonathan Marcus (9 June 2011). "BBC News - UN nuclear watchdog refers Syria to Security Council". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- "IAEA reports Syria to UN Security Council". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- Daraghi, Borzou (30 December 2011). "Syrian rebels raise a flag from the past". Retrieved 28 August 2012.

- Moubayed, Sami (6 August 2012). "Capture The Flag". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- "Syria: The virtue of civil disobedience". Al Jazeera. 6 April 2012. Retrieved 28 August 2012.

- "Syrian army tanks 'moving towards Hama'". BBC News. 5 May 2011. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- "'Dozens killed' in Syrian border town". Al Jazeera. 17 May 2011. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- "'Defected Syria security agent' speaks out". Al Jazeera. 8 June 2011. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- "Syrian army starts crackdown in northern town". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- Carsten, Paul. (2012-03-15) Syria: Bodies of 23 'extreme torture' victims found in Idlib as thousands rally for Assad. Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- Arab League delegates head to Syria over 'bloodbath'. Usatoday.com (2011-12-22). Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- "Number as a civil / military". Translate.googleusercontent.com. Retrieved 6 February 2012.

- 3,000 security forces (15 March 2011 – 27 March 2012),"Archived copy". Archived from the original on 12 September 2012. Retrieved 5 February 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) 230 security forces (28 March – 8 April),"Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 October 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) 1,117 insurgents (15 March 2011 – 10 April 2012), 3,478 civilians (15 March 2011 – 6 April 2012), total of 7,825 reported killed

- "UNICEF says 400 children killed in Syria". The Courier-Mail. 8 February 2012. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- "UNICEF says 400 children killed in Syria unrest". Google News. Geneva. Agence France-Presse. 7 February 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- Peralta, Eyder (3 February 2012). "Rights Group Says Syrian Security Forces Detained, Tortured Children: The Two-Way". NPR. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- "UNICEF says 400 children killed in Syria unrest". Daily Nation.

- UNICEF says 400 children killed in Syria | United Nations Radio. Unmultimedia.org (2012-02-07). Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- Fahim, Kareem (5 January 2012). "Hundreds Tortured in Syria, Human Rights Group Says". The New York Times.

- Syrian Arab news agency – SANA – Syria : Syria news :: Archived 6 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Sana.sy (2012-02-28). Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- Kasolowsky, Raissa (9 October 2012). "Up to 335,000 people have fled Syria violence: UNHCR". Reuters. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- Syria: Refugees brace for more bloodshed. News24 (2012-03-12). Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- Lara Jakes and Yyahya Barzanji. Syrian Kurds get cold reception from Iraqi Kurds. news.yahoo.com – Associated Press (14 March 2012)

- Syrian Refugees May Be Wearing Out Turks' Welcome. NPR (2012-03-11). Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- "Archived copy". Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- Sengupta, Kim (20 February 2012). "Syria's sectarian war goes international as foreign fighters and arms pour into country". The Independent. Antakya. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Countries/SY/ColSyriaDecember2012.pdf

- Goodenough, Patrick. "As Islamists Rise, Christians Cower in Syria and Americans Oppose Arming Rebels". CNS News. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- "Envoy to Syrian President Visits China for Talks". ABC News. 14 August 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- MacFarquhar, Neil (12 November 2011). "Arab League Votes to Suspend Syria". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- "Regional group votes to suspend Syria; rebels claim downing of jet". CNN. 14 August 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- "Why Syria could get even uglier". Global Public Square – CNN.com Blogs. 19 July 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- "Syria ambassador to Iraq, Nawaf al-Fares, defects from Assad's regime". CBS News. 12 July 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- "Syria envoy says Assad resignation is not up for discussio". BBC News. 22 August 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- "French Intelligence: Syria Used and Will Use Sarin Gas". Israel National News.

- Sanger, David E.; Schmitt, Eric (3 September 2013). "Allies' Intelligence Differs on Details, but Still Points to Assad Forces". The New York Times.

- Sayare, Scott (2 September 2013). "French Release Intelligence Tying Assad Government to Chemical Weapons". The New York Times.

- Oliphant, Roland (2 September 2013). "US intelligence on Syria gas attack 'unconvincing', says Russia". The Daily Telegraph. London.

Bibliography

- Fedden, Robin (1955). Syria: an historical appreciation. London: Readers Union — Robert Hale.

- Hinnebusch, Raymond (2002). Syria: Revolution from Above. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-28568-2.