History of Qatar

The history of Qatar from its first duration of human occupation to its formation as a modern state. Human occupation of Qatar dates back to 50,000 years ago, and Stone Age encampments and tools have been unearthed in the peninsula.[1] Mesopotamia was the first civilization to have a presence in the area during the Neolithic period, evidenced by the discovery of potsherds originating from the Ubaid period near coastal encampments.[2]

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Qatar |

|

|

Prehistory

|

|

Islamic Golden Age |

|

Post-Islamic and European era |

|

Modern age and independence |

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Qatar |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Cuisine |

|

Festivals |

| Religion |

|

Music and performing arts |

|

Media |

| Sport |

|

Monuments

|

|

Symbols

|

The peninsula fell under the domain of several different empires during its early years of settlement, including the Seleucid, the Parthians and the Sasanians. In 628 AD, the population was introduced to Islam after Muhammad sent an envoy to Munzir ibn Sawa who was the Sasanid governor of Eastern Arabia.[3] It became a pearl trading center by the 8th century.[4] The Abbasid era saw the rise of several settlements.[5] After the Bani Utbah and other Arab tribes conquered Bahrain in 1783, the Al Khalifa imposed their authority over Bahrain and mainland Qatar. Over the proceeding centuries, Qatar was a site of contention between the Wahhabi of Najd and the Al Khalifa. The Ottomans expanded their empire into Eastern Arabia in 1871,[6] withdrawing from the area in 1915 after the beginning of World War I.

In 1916, Qatar became a British protectorate and Abdullah Al Thani signed a treaty stipulating that he could only cede territory to the British in return for protection from all aggression by sea and support in case of a land attack. A 1934 treaty granted more extensive protection.[7] In 1935, a 75-year oil concession was granted to the Qatar Petroleum Company and high-quality oil was discovered in 1940 in Dukhan.[7]

During the 1950s and 1960s, increasing oil revenues brought prosperity, rapid immigration, substantial social progress, and the beginnings of the country's modern history. After Britain announced a policy of ending the treaty relationships with the Persian Gulf sheikdoms in 1968, Qatar joined the other eight states then under British protection in a plan to form a federation of Arab emirates. By mid-1971, as the termination date of the British treaty relationship approached, the nine still had not agreed on terms of union. Accordingly, Qatar declared its independence on September 3, 1971.[7] In June 1995, deputy emir Hamad bin Khalifa became the new emir after his father Khalifa bin Hamad in a bloodless coup. The emir permitted more liberal press and municipal elections as a precursor to parliamentary elections. A new constitution was approved via public referendum in April 2003 and came into effect in June 2005.[7]

Prehistory

Paleolithic Age

In 1961, a Danish archaeological expedition carried out on the peninsula uncovered approximately 30,000 stone implements from 122 paleolithic sites. Most of the sites were situated along the coastline, and were divided into four separate cultural groups based on flint typology. Macrolithic tools such as scrapers, arrowheads and hand axes dating to the lower and middle paleolithic periods were among the discoveries.[8]

The flooding of the Persian Gulf, which occurred roughly 8,000 years ago,[9] resulted in the displacement of Persian Gulf inhabitants, the formation of the Qatari Peninsula and the occupation of Qatar to capitalize on its coastal resources.[10] From this time onward, Qatar was regularly used as rangeland for nomadic tribes from the Najd and al-Hasa regions in Saudi Arabia, and a number of seasonal encampments were constructed around sources of water.[11]

Neolithic period (8000–3800 BC)

Al Da'asa, a settlement located on the northeast coast of Qatar, is the most extensive Ubaid site in the country. It was excavated by a Danish team in 1961.[12] The site is theorized to have accommodated a small sasonal encampment, possibly a lodging for a hunting-fishing-gathering group who made recurrent visits.[13] This is evidenced by the discovery of nearly sixty fire pits at the site, which may have been used to cure and dry fish, in addition to flint tools such as scrapers, cutters, blades and arrow heads. Furthermore, many painted Ubaid potsherds and a carnelian bead were found in the fire pits, suggesting overseas connections.[14]

In an excavation done in Al Khor in 1977–78, several Ubaid-period graves were uncovered in what is considered the earliest recorded burial site in the country.[15] One grave contained the cremated remains of a young woman with no grave goods. Eight other graves contained grave goods, including beads made of shell, carnelian and obsidian. The obsidian most likely originated from Najran in south west Arabia.[12][14] 235

Bronze Age (2100–1155 BC)

The Qatari Peninsula was close enough to the Dilmun civilization in Bahrain to have felt its influence.[1] Barbar pottery was excavated in two sites by the Qatar Archaeology Project, evidencing the country's involvement in Dilmun's trade network.[12] When the people of Dilmun began engaging in maritime activities around 2100 to 1700 BC, the inhabitants of Qatar started diving for pearls in the Persian Gulf.[16] The Qataris were engaged in the trading of pearls and date palms during this era.[17]

It has been argued that the remains of Dilmun settlements found in Qatar do not represent major evidence of long-term human habitation.[13] Qatar remained largely uninhabited during this period due to regular migration by nomadic Arab tribes searching for untapped sources food and water.[18] The settlements dating to the Dilmun period, particularly in Al Khor Island, may have been established to expedite trade journeys between Bahrain to the closest significant settlement in the Persian Gulf, Tell Abraq. Another scenario entails that the encampments were created by visiting fishermen or pearl fishers from Dilmun. It has also been suggested that the presence of pottery is indicative of trade between the inhabitants of Qatar and the Dilmun civilization, though this is considered unlikely due to the scarce population of the peninsula during this period.[19]

Kassite Babylonian-influenced materials dating back to the second millennium BC, which were found in Al Khor Island, reveal evidence of trade relations between the inhabitants of Qatar and the Kassite.[11] Among the findings were 3,000,000 crushed snail shells and Kassite potsherds.[12] It has been asserted that Qatar was the site of the earliest known production of shellfish dye owing to a purple dye industry operated by the Kassite which existed on the island.[2][20] The dye was obtained from the Murex snail and was known as "Tyrian purple".[12] Dye production may have been supervised by the Kassite administration in Bahrain with the purpose of exporting the dye to Mesopotamia.[21]

Antiquity

Iron Age and Babylonian–Persian control (680–325 BC)

.jpg)

Assyrian king Esarhaddon led a successful campaign against Bazu,[22] an area which encompassed Dilmun and Qatar,[23] in c. 680 BC. To date, no archaeological evidence of early Iron Age settlements have been discovered in the Peninsula.[24] This is likely due to adverse climatic changes rendering Qatar less inhabitable during this period.[25]

In the 5th century BC, Greek historian Herodotus published the earliest known description of the population of Qatar, describing its inhabitants as 'sea-faring Canaanites'.[26]

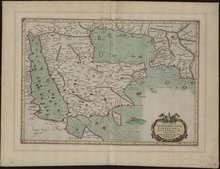

Hellenistic period (325–250 BC)

Around 325 BC,[16] Alexander the Great sent his top admiral, Androsthenes of Thasos, to survey the entire Persian Gulf. The requested charts arrived shortly after Alexander died in 323.[27] Seleucus I Nicator was awarded the eastern part of the Ancient Greek Empire after Alexander's death. Starting from 312, he expanded the Seleucid Empire eastward of Babylon, purportedly encompassing parts of Eastern Arabia.[28] Archaeological evidence of Greek-influenced materials has been discovered in Qatar. Excavations north of Dukhan uncovered potsherds of Seleucid characteristic, and a cairnfield consisting of 100 burial mounds dating to the era was discovered in Ras Abrouq.[12][29] The relatively large number of cairns suggest a sizeable sea-faring community prevailed in the area.[30]

After losing most of their territories in the Persian Gulf, Seleucid influence ceased in the area by c. 250 BC.[5][31]

Persian control (250 BC–642 AD)

Following the eviction of the Seleucid by the Parthian Empire in c. 250 BC, the latter gained dominion over the Persian Gulf and Arabian Coast.[5][31] As the Parthians were dependent on trade routes through the Persian Gulf, they established garrisons along the coast.[5] Pottery recovered from expeditions in Qatar has demonstrated links to the Parthian Empire.[32]

Ras Abrouq, a coastal city north of Dukhan, housed a fishing station which foreign vessels used to dry fish in 140 BC.[33] A number of stone structures and large quantities of fish bones were recovered from the site.[30]

Pliny the Elder, a Roman author, wrote an account on the inhabitants of the peninsula around the mid-first century AD. He referred to them as the "Catharrei" and described them as nomads who constantly roamed in search of water and food.[30] Around the second century, Ptolemy produced the first known map to depict the landmass, referring to it as "Catura".[34]

In 224 AD, the Sasanian Empire gained control over the territories surrounding the Persian Gulf.[31] Qatar played a role in the commercial activity of the Sasanids, contributing to at least two commodities: precious pearls and purple dye.[35] Sasanid pottery and glassware were found in Mezru'ah, a city north-west of Doha, and fragments of glassware and pottery were discovered in a settlement in Umm al-Ma'a.[12]

Under the Sasanid reign, many of the inhabitants in Eastern Arabia were introduced to Christianity after the religion was dispersed eastward by Mesopotamian Christians.[36] Monasteries were constructed in Qatar during this era,[37] and further settlements were founded.[33] During the latter part of the Christian era, Qatar was known by the Syriac name 'Beth Qatraye' (ܒܝܬ ܩܛܪܝܐ; "region of the Qataris").[38] A variant of this was 'Beth Catara'.[39] The region was not limited to Qatar; it also included Bahrain, Tarout Island, Al-Khatt, and Al-Hasa.[40] The dioceses of Beth Qatraye did not form an ecclesiastical province, except for a short period during the mid-to-late seventh century. They were instead subject to the Metropolitan of Fars.[41]

Muhammad sent Al-Ala'a Al-Hadrami, a Muslim envoy, to a Persian ruler in Eastern Arabia named Munzir ibn Sawa Al Tamimi in 628 and requested that he and his people accept Islam. Munzir obliged his request and most Arab tribes in Qatar converted to Islam.[3] It has been proposed by historian Habibur Rahman that Munzir ibn Sawa's seat of administration existed in the Murwab or Umm al-Ma'a area of Qatar. This theory is lent credence by an archaeological find of approximately 100 small stone-built Islamic-period houses and fortified palaces of a tribal leader in Murwab, which are thought to have originated from the early Islamic period.[42] After the adoption of Islam, the Arabs led the Muslim conquest of Persia which resulted in the fall of the Sasanian Empire.[43]

It is likely that some settled populations in Qatar did not immediately convert to Islam. Isaac of Nineveh, a 7th-century Syriac Christian bishop regarded as a saint in some churches, was born in Beth Qatraye.[43][44] Other notable Christian scholars dating to this period who hailed from Beth Qatraye include Dadisho Qatraya, Gabriel of Qatar and Ahob of Qatar. In 674, the bishops of Beth Qatraye stopped attending synods.[41]

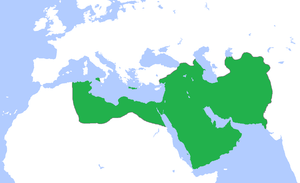

Muslim rule

Umayyad period (661–750)

Qatar was described as a famous horse and camel breeding centre during the Umayyad period.[42] It began benefiting from its commercially strategic position in the Persian Gulf during the 8th century,[45] going on to become a center of pearl trading.[4]

During the Second Fitna, a renowned Khariji commander named Qatari ibn al-Fuja'a, who was described as the most popular, admired and powerful Khariji leader,[46] led the Azariqa, a sub-sect of the Khawarij, in to numerous battles.[47] He held the title of Amir al-Mu'minin and ruled over the radical Azariqa movement for more than 10 years.[48] Born in Al Khuwayr in Qatar,[49] he also minted the first known Kharjite coins, the earliest of which dated to 688 or 689.[47]

The Umayyad Caliphate brought about much political and religious change in western Asia starting from the late seventh century.[50] As a result, there were many revolts against the Umayyad at the end of the seventh century, particularly in Qatar and Bahrain.[48] Ibn al-Fuja'a led an uprising against the Umayyad caliphs for more than twenty years.[46]

In 750, discontent in the caliphate had reached a critical level due to the treatment of non-Arab citizens in the Empire. The Abbasid Revolution resulted in the overthrow of the Umayyad Caliphate, ushering in the Abbasid period.[51]

Abbasid period (750–1253)

Several settlements, including Murwab, were developed during the Abbasid period.[5] Over 100 stone-built houses, two mosques, and an Abbasid fort were constructed in Murwab during this era.[42][52][53] Murwab fort is the oldest intact fort in the country and was built over the ruins of a previous fort which was destroyed by fire. The town was the site of the first sizable settlement established off the coastal area of Qatar.[12] A similar site, containing T'ang stoneware and dating to the 9th and 10th centuries, was discovered in Al Naman (north of Zubarah).[52]

Substantial development in the pearling industry around the Qatari Peninsula occurred during the Abbasid era.[42] Ships from Basra en route to India and China would make stops in the port of Qatar during this period. Chinese porcelain, West African coins and pieces from Thailand have been discovered in Qatar.[43] Archaeological remains from the 9th century suggest that Qatar's inhabitants used greater wealth, perhaps from pearl trade, to construct higher quality homes and public buildings. However, when the caliphate's prosperity declined in Iraq, so too did it in Qatar.[54]

Most of Eastern Arabia, particularly Bahrain and the Qatari Peninsula, were sites of revolt against the Abbasid Caliphate around 868.[55] Mohammed ibn Ali, a revolutionary, roused the people of Bahrain and Qatar into a rebellion, but the rebellion was unsuccessful and he relocated to Basra. He was later successful in instigating the Zanj Rebellion.[56]

A radical Isma'ili group called the Qarmatians established a utopian republic in Eastern Arabia in 899.[57] They considered the pilgrimage to Mecca a superstition and once in control of the Bahraini state they launched raids along the pilgrim routes crossing the Arabian Peninsula. In 906 they ambushed the pilgrim caravan returning from Mecca and massacred 20,000 pilgrims.[58]

Qatar is mentioned in 13th-century Muslim scholar Yaqut al-Hamawi's book, Mu'jam Al-Buldan (Dictionary of Countries), which alludes to the Qataris' fine striped woven cloaks and their skills in improvement and finishing of spears, known as khattiyah spears.[59] The spears acquired their name as an homage to the region of Al-Khatt which encompassed present-day Qatif, Uqair and Qatar.[52]

Post-Islamic Golden Age

Usfurids and Ormus control (1253–1515)

Much of Eastern Arabia was controlled by the Usfurids in 1253, but control of the region was later seized by the prince of Ormus in 1320.[60] Qatar's pearls provided the kingdom with one of its main sources of income.[27] The Portuguese defeated the Ormus by 1507 following the destruction of their fleet by Afonso de Albuquerque's forces. However, Albuquerque's captains grew rebellious and he was compelled to abandon the Ormus island. Ultimately, in 1515, King Manuel I killed Sultan Saifuddin's vizier Reis Hamed, pressuring the sultan to become a vassal of King Manuel.[61]

Portuguese and Ottoman control (1521–1670)

Bahrain and mainland Qatar had been seized by the Portuguese in 1521.[27][62] After the Portuguese claimed control, they constructed a series of fortresses along the Arabian Coast.[62] However, there have been no significant Portuguese ruins found in Qatar.[16] The Portuguese focused on creating a commercial empire in Eastern Arabia, and exported gold, silver, silks, cloves, amber, horses and pearls.[63] The population of Al-Hasa submitted voluntarily to the rule of the Ottomans in 1550, preferring them to the Portuguese.[64]

After the Portuguese were expelled from the area in 1602[65] by the Dutch and British,[66] the Ottomans saw little need to maintain a military presence in the Al-Hasa region. As a result, the Ottomans were expelled by the Bani Khalid in 1670.[66]

Origin of the Bani Utbah Tribe

The Al Bin Ali Tribe are the original descendants of Bani Utbah tribe being that they are the only tribe to carry and nurture the last name Al-Utbi in their Ownership's documents of Palm gardens in Bahrain as early as the year 1699 - 1111 Hijri.[67] They are specifically descendants of their great grand father Ali Al-Utbi who is a descendant of their great grand father Utbah hence the name Bani Utbah which means sons of Utbah. Utbah is the great grandfather of the Bani Utbah which is a section of Khafaf from Bani Sulaim bin Mansoor from Mudhar from Adnan. The plural word for Al-Utbi is Utub and the name of the tribe is Bani Utbah.

Rule of Bani Khalid (1670–1783)

Having expelled the Ottomans, the Bani Khalid held jurisdiction over Qatar from 1670 onward.[68] In 1766,[69] the Utub clans of Al Jalahma and Al Khalifa migrated from Kuwait to Zubarah in Qatar.[70] By the time of their arrival in Zubarah, the Bani Khalid exercised weak power over Qatar, though the largest village was ruled by distant kin of the Bani Khalid.[71] After the Persian Occupation of Basra in 1777 many merchants and families moved from Basra and Kuwait to Zubarah. The town became a thriving center of trade and pearling in the Persian Gulf region after this movement.[72]

The Al Khalifa claimed Qatar and Bahrain by 1783, whereas Bani Khalid control of neighboring Al-Hasa officially came to an end in 1795.[73]

Al Khalifa and Saudi control (1783–1868)

_1794.jpg)

Following Persian aggression towards Zubarah, the Utub and other Arab tribes drove out the Persians from Bahrain in 1783.[72][74] Al Jalahma seceded from the Utub alliance sometime before the Utub annexed Bahrain in 1783 and returned to Zubarah. This left the Al Khalifa tribe in undisputed possession of Bahrain,[75] who then transferred their power base from Zubarah to Manama. They continued to exert authority over the mainland, and paid tribute to the Wahhabi to ward off challenges on Qatar.[69] However, Qatar did not develop a centralized authority because the Al Khalifa oriented their focus towards Bahrain. As a result, Qatar went through many periods of 'transitory sheikhs', with the most notable being Rahmah ibn Jabir al-Jalahimah.[71] By 1790, Zubarah was described as a safe heaven for merchants who enjoyed complete protection and no customs duties.[76]

The town came under threat by the Wahhabi from 1780 onward due to the intermittent raids launched on the Bani Khalid strongholds in Al-Hasa.[77] The Wahhabi speculated that the population of Zubarah would conspire against their regime with the help of the Bani Khalid. They also believed that its residents practiced teachings contrary to the Wahhabi doctrine, and regarded the town as an important gateway to the Persian Gulf.[78] Saudi general Sulaiman ibn Ufaysan led a raid against the town in 1787. Five years later, a massive Wahhabi force conquered Al Hasa, forcing many refugees to flee to Zubarah.[15][79] Wahhabi forces besieged Zubarah and several neighboring settlements in 1794 later as punishment for accommodating asylum seekers.[12][15] The local chieftains were allowed to continue carrying out administrative tasks but were required to pay a tax.[80]

After defeating the Bani Khalid in 1795, the Wahhabi were attacked on two fronts. The Ottomans and Egyptians assaulted the western front, while the Al Khalifa in Bahrain and the Omanis launched an attack against the eastern front.[81][82] The Wahhabi allied themselves with the Al Jalahmah tribe in Qatar, who proceeded to engage the Al Khalifa and Omanis on the eastern frontier.

Upon being made aware of advancements by the Egyptians on the western frontier, in 1811, the Wahhabi amir reduced his garrisons in Bahrain and Zubarah in order to re-position his troops. Said bin Sultan of Muscat capitalized on this opportunity and attacked the Wahhabi garrisons in Bahrain and Zubarah. The fort in Zubarah was set ablaze and the Al Khalifa were effectively returned to power.[82]

British involvement

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

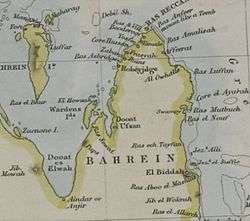

Britain's desire for secure passage for East India Company ships led it to impose its own order in the Persian Gulf. An agreement known as the General Maritime Treaty was signed between the East India Company and the sheikhs of the coastal area (later to be known as the Trucial Coast) in 1820. It acknowledged British authority in the Persian Gulf and sought to end piracy and the slave trade. Bahrain became a party to the treaty, and it was assumed that Qatar, as a dependency, was also a party to it.[1]

A report compiled by Major Colebrook in 1820 gives the first descriptions of the major towns in Qatar. All of the coastal cities mentioned in his report were situated near the Persian Gulf pearl banks and had been practicing pearl fishing for millenniums.[83] Until the late eighteenth century, all of the principal towns of Qatar including Al Huwaila, Fuwayrit, Al Bidda and Doha were situated on the east coast. Doha developed around the largest of these, Al Bidda. The population consisted of nomadic and settled Arabs and a significant proportion of slaves brought from East Africa.[1] As punishment for piracy committed by the inhabitants of Doha, an East India Company vessel bombarded the town in 1821. They razed the town, forcing between 300 and 400 natives to flee.[84]

A survey carried out by the British in 1825 notes that Qatar did not have a central authority and was governed by local sheikhs.[85] Doha was ruled by the Al-Buainain tribe. In 1828, a member of the Al-Buainain murdered a native of Bahrain, prompting the Bahraini sheikh to imprison the offender. The Al-Buainain tribe revolted, provoking the Al Khalifa to destroy their fort and expel them from Doha. The expulsion of the Al-Buainain granted the Al Khalifa more jurisdiction over Doha.[86]

Bahraini–Saudi contention

Desiring to keep surveillance over the proceedings of the Wahhabi, Bahrain stationed a government official named Abdullah bin Ahmad Al-Khalifa on the coast of Qatar as early as 1833.[86] Turning against the Bahrainis, he instigated the people of Al Huwailah to revolt against the Al Khalifa and open up a correspondence with the Wahhabi in 1835. Shortly after the revolt, a peace agreement was signed by both parties under the mediation of the son of the Sultan of Muscat. As part of the stipulations, Al Huwailah was demolished and its residents were removed to Bahrain. Nephews of Abdullah bin Ahmed almost immediately violated the agreement when they incited members of the Al Kuwari tribe to attack Al Huwailah, however.[86][87]

Residents of the peninsula were susceptible to skirmishes between the forces of the sheikh of Bahrain and the Egyptian military commander of Al-Hasa. At the end of 1839 or beginning of 1840, the governor of Al-Hasa dispatched troops to lay waste to Qatar following the refusal of the Al Nuaim tribe of Zubarah to pay the demanded tribute. The assassination of a governor in Hofuf prematurely ended the expedition before the forces could reach the country.[87]

In 1847, Abdullah bin Ahmed Al Khalifa and a Qatari chief named Isa bin Tarif formed a coalition against Mohammed bin Khalifa, the ruler of Bahrain. In November, bin Khalifa landed in Al Khor with 500 troops and military support from the governors of Qatif and Al-Hasa. The opposition forces numbered 600 troops and were led by bin Tarif. On 17 November, a decisive battle, which came to be known as the Battle of Fuwayrit, took place between the coalition forces and the Bahraini forces. The coalition forces were defeated after bin Tarif and eighty of his men were killed.[88] After he defeated the resistance troop, bin Khalifa demolished Al Bidda and moved its inhabitants to Bahrain. He sent his brother, Ali bin Khalifa, as an envoy to Al Bidda. However, he did not exercise any administrative powers, and local tribal leaders remained responsible for the internal affairs of Qatar.[89]

After having concocted a plan to invade Bahrain, the Wahhabi amir Faisal bin Turki left his headquarters in Najd with a platoon of troops in February 1851. Several offers of appeasement were made on behalf of Mohammed bin Khalifa, but these were met with rejection by Faisal. In anticipation of the impending invasion, Ali bin Khalifa moved to enlist military support in Qatar, but Mohammed bin Thani was persuaded to grant support to Faisal's forces when they reached Al Bidda in May.[90] On June 8, forces loyal to Al Thani took possession of an important tower situated close to Ali bin Khalifa's residence in the Al Bidda Fort. This prompted Bahrain to initiate negotiations for a protective treaty with the British in an attempt to thwart Faisal's advances. They were initially unsuccessful in doing so, but the British reconsidered their position after receiving an intelligence report on the conflict and hastily situated a naval blockade in Manama. Accompanying a peace treaty on 25 July 1851, the sheikh of Bahrain agreed to pay a fee of 4,000 German krones in return for the restoration of the Bahraini-occupied Al Bidda Fort and the disassociation of the Wahhabi from the inhabitants of Qatar.[91]

Economic repercussions

In a move which angered Mohammed bin Khalifa, Faisal bin Turki provided a safe haven for Abdullah bin Ahmed's sons in Dammam in 1852. Consequently, the Bahrainis attempted to drive away residents of Al Bidda and Doha who were suspected of being loyal to the Wahhabi by imposing an economic blockade on the inhabitants which prevented them from engaging in pearl hunting. The blockade continued until the end of the year.[92] In February 1853, the Wahhabi began marching from Al-Hasa to Al Khor. After Bahrain received assurance from the Qatar that they would not cooperate with the Wahhabi forces if they crossed into their borders, they sent Ali bin Khalifa to the mainland to act as a collaborator with the local resistance. A British-mediated peace agreement was reached between the two parties in 1853.[92]

Hostilities were provoked again after the Bahraini sheikh, in response to the harboring of Bahraini fugitives in Dammam, stopped paying tribute to the Wahhabi amir in 1859 and proceeded to instigate Qatari tribes to attack its subjects. Following threats made by Abdullah bin Faisal to attack Bahrain, the British navy dispatched a ship off the coast of Dammam to prevent any attacks. The situation escalated in May 1860 when Abdullah threatened to occupy the coast of Qatar until the annual tribute was paid. In May 1861, Bahrain signed a treaty with the British government in which the latter agreed to offer protection and recognize Qatar as a dependent of Bahrain.[93] In February 1862, the treaty was ratified by the Indian government.[94]

Proceeding the British involvement, the sway that the Al Khalifa tribe held over Qatar's affairs began declining. Mohammed bin Thani was described by Gifford Palgrave as the acknowledged governor of the Qatar Peninsula in 1863.[95] Some of Al Wakrah's inhabitants were forced to vacate the town by the Bahraini sheikh in April 1863 due to alleged links with the Wahhabi. The town's chief, Mohammed Bu Kuwara, was taken into custody on a similar charge.[96] In 1866, a report by the British revealed that Qatar was paying an annual zakat of 4,000 German krones to the Wahhabi, in encroachment of the 1861 British treaty. The report also contended that the Al Khalifa were taxing the people of Qatar for the same annual payment.[97]

Qatari–Bahraini War

In June 1867, a representative of Mohammed Al Khalifa seized a Bedouin from Al Wakrah and deported him to Bahrain. Mohammed bin Thani demanded his release, but the representative refused. This prompted Mohammed bin Thani to expel him from Al Wakrah. Upon receiving news of this, Mohammed Al Khalifa released the Bedouin prisoner and expressed his desire of renewed peace talks. Jassim bin Mohammed Al Thani, the son of Mohammed bin Thani, traveled to Bahrain to negotiate on his behalf. He was imprisoned on arrival and a large number of ships and troops were soon sent to punish the people of Al Wakrah and Al Bidda. Abu Dhabi joined on Bahrain's behalf due to the conception that Al Wakrah served as a refuge for fugitives from Oman. Later that year, the combined forces sacked the two aforementioned Qatari cities with 2,000 men in what would come to be known as the Qatari–Bahraini War.[98][99] A British record later stated:

"(...) the towns of Doha and Wakrah were, at the end of 1867 temporarily blotted out of existence, the houses being dismantled and the inhabitants deported."

In June 1868, Qatari tribes retaliated against Bahrain and a battle ensued in which 60 boats were sunk and 1000 men were killed. Afterwards, the Bahraini sheikh agreed to free Jassim bin Mohammed in return for captured Bahraini prisoners.[100]

The joint Bahraini-Abu Dhabi incursion and Qatari counterattack prompted the British political agent, Colonel Lewis Pelly, to impose a settlement in 1868. Pelly's mission to Bahrain and Qatar and the peace treaty that resulted were milestones in Qatar's history. It implicitly recognized the distinctness of Qatar from Bahrain and explicitly acknowledged the position of Mohammed bin Thani as an important representative of the Peninsula's tribes.[101]

Ottoman control (1871–1915)

The Ottoman Empire expanded into Eastern Arabia in 1871. After establishing themselves on Al-Hasa coast, they advanced towards Qatar. Al Bidda soon came to serve as a base of operations for Bedouins harassing the Ottomans in the south, and Abdullah II Al-Sabah of Kuwait was sent to the town to secure a landing for the Ottoman troops. He brought with him four Ottoman flags for the most influential personages in Qatar. Mohammed bin Thani received and accepted one of the flags, but he sent it to Al Wakrah and continued hoisting the local flag above his house. Jassim bin Mohammed accepted a flag and flew it above his house. A third flag was given to Ali bin Abdul Aziz, the ruler of Al Khor.

The British reacted negatively to the Ottoman's advancements as they felt their interests were at stake. Receiving no response to their objections, the British gunboat Hugh Rose arrived in Qatar on 19 July 1871. After inspecting the situation, Sidney Smith, the assistant political resident in the Persian Gulf, discovered that Qatar flew the flags willingly.[6] To further add to their apprehension, Jassim bin Mohammed, who assumed his father's role during this period, authorized the Ottomans to send 100 troops and equipment to Al Bidda in December 1871. By January 1872, the Ottomans incorporated Qatar into their dominion. It was designated a province in Najd under the control of the sanjak of Najd. Jassim bin Mohammed was appointed as the Kaymakam (sub-governor) of the district, and most other Qataris were allowed to keep their positions in the new government.[102]

Charles Grant, the assistant political resident, falsely reported that the Ottomans sent a contingent of 100 troops from Qatif to Zubarah under the command of Hossein Effendi in August 1873. The sheikh of Bahrain reacted negatively to this because the Al Nuaim tribe which resided in Zubarah had signed a treaty agreeing to be subjects of his. Upon being confronted by the sheikh, Grant referred him to political resident Edward Ross. Ross informed the sheikh that he believed he had no right to protect tribes residing in Qatar.[103] In September, the sheikh reiterated his sovereignty over the town and tribe. Grant replied by arguing that there was no special mention of the Al Nuaim or Zubarah in any treaties signed with Bahrain. A British government official concurred with his views, stating that the sheikh of Bahrain "should, as far as practicable abstain from interfering in complications on the mainland."[104]

Another chance arose for the Al Khalifa to renew their claim on Zubarah in 1874 after an opposition leader named Nasir bin Mubarak moved to Qatar. They believed that Mubarak, with the assistance of Jassim bin Mohammed, would target the Al Nuaim living in Zubarah as a prelude to an invasion. As a result, a contingent of Bahraini reinforcements were sent to Zubarah, much to the disapproval of the British who suggested that the sheikh was involving himself in complications. Edward Ross made it apparent that a government council decision advised the sheikh that he should not interfere in the affairs of Qatar.[105] The Al Khalifa remained in consistent contact with the Al Nuaim, drafting 100 members of the tribe in their army and offering financial assistance. Jassim bin Mohammed expelled some members of the tribe after they attacked ships near Al Bidda in 1878.[106]

Despite the opposition of many prominent Qatari tribes, Jassim bin Mohammed continued to show support for the Ottomans. However, there were no signs of improvement in the partnership between the two parties, and relations further deteriorated when the Ottomans refused to aid Jassim in his expedition of Abu Dhabi-occupied Khawr al Udayd in 1882. In addition, the Ottomans supported the Ottoman subject Mohammed bin Abdul Wahab who attempted to supplant Jassim bin Mohammed in 1888.[107]

Battle of Al Wajbah

In February 1893, Mehmed Hafiz Pasha arrived in Qatar in the interests of seeking unpaid taxes and accosting Jassim bin Mohammed's opposition to proposed Ottoman administrative reforms. Fearing that he would face death or imprisonment, Jassim bin Mohammed moved to Al Wajbah (10 miles west of Doha); he was accompanied by several tribe members. Mehmed demanded that he disband his troops and pledge his loyalty to the Ottomans. However, Jassim bin Mohammed remained adamant in his refusal to comply with Ottoman authority. In March 1893, Mehmed imprisoned his brother, Ahmed bin Mohammed Al Thani, in addition to 13 prominent Qatari tribal leaders on the Ottoman corvette 'Merrikh'. After Mehmed declined an offer to release the captives for a fee of ten thousand liras, he ordered a column of approximately 200 Ottoman troops to advance towards Jassim bin Mohammed's fortress in Al Wajbah under the command of Yusuf Effendi.[108]

Shortly after arriving to Al Wajbah, Effendi's troops came under heavy gunfire by Qatari infantry and cavalry troops, which totaled 3,000 to 4,000 men. They retreated to Shebaka fortress, where they once again sustained casualties from a Qatari incursion. After they retreated to the fortress of Al Bidda, Jassim bin Mohammed's advancing column besieged the fortress and cut off the water supply of the neighborhood. The Ottomans conceded defeat and agreed to relinquish the Qatari captives in return for the safe passage of Mehmed Pasha's cavalry to Hofuf by land.[109] Although Qatar did not gain full independence from the Ottoman Empire, the result of the battle forced a treaty that would later form the basis of Qatar emerging as an autonomous separate country within the empire.[110]

Later Ottoman presence

On the cusp of Ottoman withdrawal from the Peninsula in 1915, the British government wrote the following description of the Ottoman presence in Qatar:

"The Qatar Peninsula, to the east of the island of Bahrain, is ruled by Shaikh ’Abdullah bin Jasim, a rich and powerful chief, who has a following of about 2,000 lighting men. Some few years ago his father was engaged in hostilities with the Turks, who succeeded, after some hard fighting, in establishing a garrison in the fort of Al Bida’ (Dohah) on the eastern side of the peninsula and in reducing Jasim to nominal subjection. He is now styled qaim-maqam of the peninsula under the Porte, and flies the Turkish flag, but he dislikes his rulers and would be glad to be rid of them. The Bani Hajar tribes can muster about 4,500 fighting men, which with the Shaikh’s 2,000, would give altogether 6,500; but 4,500 represents as large a force as he is ever likely to bring together. Since about 1900 various attempts have been made by the Porte to assert its sovereignty in other parts of the Qatar peninsula, and in 1910 Turkish mudirs were to be despatched to Zubarah, Odaid, Wakrah, and Abu ’Ali Island. His Majesty’s Government, however, protested against this, and, indeed, have never acknowledged Turkish rule in Qatar. In 1913 Turkey consented to remove her garrison from Qatar; but that agreement has not yet been signed, hence the garrison remains.

The Turkish garrison lives in the fort of Al Bida’, which is in the centre of the town and a little back from the sea. The garrison consists of, at the most, 100 infantry and there are said to be 12 gunners in charge of two old guns. There is an outpost of eight Turkish soldiers in a tower, over the well of Rushairib, about a mile from the fort.[111]

Shaikh Abdullah, who succeeded to the chiefship of Qatar in 1913, is friendly towards the British, and afraid of Bin S’aud. He would no doubt be glad to be rid of the Turks."[112]

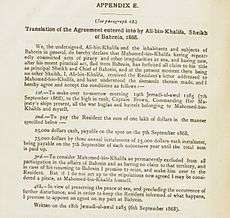

British protectorate (1916–1971)

The Ottomans officially renounced sovereignty over Qatar in 1913, and in 1916 the new ruler Abdullah bin Jassim Al Thani signed a treaty with Britain, thereby instating the area under the trucial system. This meant that Qatar relinquished its autonomy in foreign affairs, such as the power to cede territory, and other affairs, in exchange for Britain's military protection from external threats. The treaty also had provisions suppressing slavery, piracy, and gunrunning, but the British were not strict about enforcing those provisions.[1]

Despite Qatar coming under British protection, Abdullah bin Jassim's position was insecure. Recalcitrant tribes refused to pay tribute; disgruntled family members intrigued against him; and he felt vulnerable to the designs of Bahrain and the Wahhabi. The Al Thani were merchant princes, reliant on trade and especially the pearl trade, and dependent on other tribes to do their fighting for them, primarily the Bani Hajer who owed their allegiance to Ibn Saud, amir of the Najd and Al-Hasa. Despite numerous requests by Abdullah bin Jassim for strong military support, weapons, and a loan, the British were reluctant to become involved in inland affairs. This changed in the 1930s, when competition for oil concessions in the region intensified.

Oil drilling

The scramble for oil raised the stakes in regional territorial disputes and signified the need to establish territorial borders. The first move came in 1922 at a boundary conference in Uqair when prospector Major Frank Holmes attempted to include Qatar in an oil concession he was discussing with Ibn Saud. Sir Percy Cox, the British representative, saw through the ploy and drew a line on the map separating the Qatar Peninsula from the mainland.[113] The first oil survey took place in 1926 under the direction of George Martin Lees, a geologist contracted to the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, but no oil was found. The oil issue raised its head again in 1933 after an oil strike in Bahrain. Lees had already noted that, in such an eventuality, Qatar should be investigated again.[114] After lengthy negotiations on 17 May 1935, Abdullah bin Jassim signed a concession agreement with Anglo-Persian representatives for a period of 75 years in return for 400,000 rupees on signature and 150,000 rupees per annum with royalties.[115] As part of the agreement, Great Britain made more specific promises of assistance than they had in earlier treaties.[1] Anglo-Persian transferred the concession to the IPC subsidiary company Petroleum Development (Qatar) Ltd. in order to meet its obligations under the Red Line Agreement.

Bahrain claimed rule over a group of islands encompassing the two countries in 1936. The largest island was Hawar Islands, situated off the west coast of Qatar, where the Bahrainis had established a small military garrison. Britain accepted the Bahraini claim over Abdullah bin Jassim's objections, in large part because the Bahraini sheikh's personal British adviser was able to phrase their case in a legal manner familiar to British officials. In 1937, the Bahrainis again laid claim to the deserted town of Zubarah after being involved in a dispute involving the Al Nuaim tribe. Abdullah bin Jassim sent a large, heavily armed force and succeeded in defeating the Al Nuaim. The British political resident in Bahrain supported Qatar's claim and warned Hamad ibn Isa Al Khalifa, the ruler of Bahrain, not to intervene militarily. Indignant over the loss of Zubarah, Hamad ibn Isa imposed a crushing embargo on trade and travel to Qatar.[1]

Drilling of the first oil well began in Dukhan in October 1938 and over a year later, the well struck oil in the Upper Jurassic limestone. Unlike the Bahraini strike, this was similar to Saudi Arabia's Dammam field discovered three years before.[116] Production was halted between 1942 and 1947 because of World War II and its aftermath. The disruption of food supplies caused by the war prolonged a period of economic hardship in Qatar which began in the 1920s with the collapse of the pearl trade and was exacerbated in the early 1930s with the onsets of the Great Depression and the Bahraini embargo. As was the case in previous times of privation, entire families and tribes moved to other parts of the Persian Gulf, leaving many Qatari villages deserted. Abdullah bin Jassim went into debt and groomed his favored second son, Hamad bin Abdullah Al Thani, to be his successor in preparation for his retirement. However, Hamad bin Abdullah's death in 1948 led to a succession crisis in which the main candidates were Abdullah bin Jassim's eldest son, Ali bin Abdullah Al Thani, and Hamad bin Abdullah's teenage son, Khalifa bin Hamad Al Thani.[1]

Oil exports and payments for offshore rights began in 1949 and marked a turning point in Qatar. The oil revenues would dramatically transform the economy and society and would also provide the focus for domestic disputes and foreign relations. This became apparent to Abdullah bin Jassim when several of his relatives threatened armed opposition if they did not receive increases in their allowances. Aged and anxious, Abdullah bin Jassim turned to the British. He promised to abdicate and agreed to an official British presence in Qatar in exchange for recognition and support of Ali bin Abdullah as ruler in 1949.[1]

Under British tutelage, the 1950s witnessed the development of government structures and public services. Ali bin Abdullah was at first reluctant to share power, which had centered in his household, with an infant bureaucracy run and staffed mainly by outsiders. Ali bin Abdullah's increasing financial difficulties and inability to control striking oil workers and obstreperous sheikhs led him to succumb to British pressure. The first official budget was drawn up by a British adviser in 1953. By 1954 there were forty-two Qatari government employees.[1]

Protests and reforms

Large numbers of protests against the British and the ruling family occurred during the 1950s. One of the largest protests took place in 1956; it drew 2,000 participants, most of whom were high-ranking Qataris allied with Arab nationalists and dissatisfied oil workers.[117] During another protest which took place in August 1956, the participants waved Egyptian flags and chanted anti-colonialism slogans.[118] In October 1956, protesters tried to sabotage oil pipelines in the Persian Gulf by destroying the pipelines with a bulldozer.[118] These were major impetuses to the development of the British-run police force which was established by the British in 1949.[119] The demonstrations led Ali bin Abdullah to invest the police with his personal authority and support. This was a significant reversal of his previous reliance on his retainers and Bedouin fighters.[1]

Public services developed slowly during the 1950s. The first telephone exchange opened in 1953, the first desalination plant in 1954, and the first power plant in 1957. Also built in this period were a dock, a customs warehouse, an airstrip, and a police headquarters. In the 1950s, 150 adult males of the ruling family received grants from the government. Sheikhs also received land and government positions. This mollified them as long as oil revenues increased. However, when revenues declined in the late 1950s, Ali bin Abdullah could not handle the family pressures this engendered. Discontent was fueled by his residence in Switzerland, extravagant spending, and hunting trips in Pakistan, especially among those who were excluded from the regime's largesse (non-Al Thani Qataris) and among other branches of Al Thani who desired more privileges. Seniority and proximity to the sheikh determined the size of allowances.[1]

Succumbing to family pressures and poor health, Ali bin Abdullah abdicated in 1960. Instead of handing power over to Khalifa bin Hamad, who had been named heir apparent in 1948, he made his son, Ahmad bin Ali, ruler. Nonetheless, Khalifa bin Hamad gained considerable power as heir apparent and deputy ruler, in large part because Ahmad bin Ali spent much time outside the country.[1] One of his first acts was to increase funding for the sheikhs at the expense of development projects and social services. In addition to allowances, adult male Al Thani were given government positions. This added to the anti-regime resentment already felt by, among others, oil workers, low-ranking Al Thani, dissident sheikhs, and some leading government officials. These individuals formed the National Unity Front in response to a fatal shooting of a protester on 19 April 1963 by one of Sheikh Ahmad bin Ali's nephews.[120] While the Saudi monarch was at the ruler's palace on 20 April 1963, a demonstration occurred in front of the building. Police fired and killed three demonstrators, prompting the National Unity Front to organize a general strike on 21 April.[118] The strike lasted around two weeks, and most public services were affected.[121]

The group made a statement that week where it listed 35 of its demands to the government entailing less authority for the ruling family; protection for oil workers; recognition of trade unions; voting rights for citizens and the Arabization of the leadership.[118][121] Ahmed bin Ali rejected most of these demands and moved to arrest and detain fifty of the most prominent National Unity Front members and sympathizers without trial in early May.[122] The government also instituted some reforms in response to the movements. This included the provision of land and loans to poor farmers, instituting a policy of preferential hiring of Qatari citizens, and the election of a municipal council.[1][123]

The infrastructure, foreign labor force, and bureaucracy continued to grow in the 1960s, largely under the instruction of Khalifa bin Hamad. There were also some early attempts at diversifying Qatar's economic base, most notably with the establishment of a cement factory, a national fishing company, and small-scale agriculture.[1] An official gazette was first published in 1961, and in 1962, a nationality law was introduced.[124] No cabinets existed during this period, however, British and Egyptian advisers helped establish a number of governmental departments, such as the Department of Agriculture and a Department of Labor and Social Affairs.[124]

Federation of nine Emirates

In 1968, Britain announced its plans of withdrawing its military commitments east of Suez (including those in force with Qatar) in the proceeding three years. Because of the Persian Gulf sheikhdoms' vulnerability and small size, the rulers of Bahrain, Qatar and the Trucial Coast contemplated forming a federation after the British withdrawal.[125] The federation was first proposed in February 1968, when the rulers of Abu Dhabi and Dubai announced their intention to form a coalition, extending an invitation to other Gulf states to join. Later that month, in a summit meeting attended by the rulers of Bahrain, Qatar and the Trucial Coast, the government of Qatar proposed the formation of a federation of Arab Emirates to be governed by a higher council composed of nine rulers. This proposal was accepted and a declaration of union was approved.[125] There were, however, several disagreements between the rulers on matters such as the location of the capital, the drafting of the constitution and the distribution of ministries.[125]

The rulers remained divided on multiple issues despite Khalifa bin Hamad's election as chairman of the Temporary Federal Council in July 1968 and the establishment of numerous ministries. Two opposing blocs surfaced soon after the initial proposal, with Qatar and Dubai aligning together to oppose the inclinations of Bahrain and Abu Dhabi.[125] Bahrain, being backed by Abu Dhabi, made efforts to marginalize the other rulers' roles in the union in an attempt to assume a leadership role and thus gain political leverage over their long-standing territorial disputes with Iran. The last meeting took place in October 1969 when Zayed Al Nahyan and Khalifa bin Hamad were elected the first president and prime minister of the federation, respectively. There were stalemates on numerous issues during the meeting, including the position of vice-president, the defense of the federation, and whether a constitution was required.[126] Shortly after the meeting, the Political Agent in Abu Dhabi revealed the British government's interests in the outcome of the session, prompting Qatar and Ras al-Khaimah to withdraw from the federation over perceived foreign interference in internal affairs. The federation was consequently disbanded despite efforts by Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Britain to reinvigorate discussions.[127]

Ahmad bin Ali subsequently promulgated a provisional constitution in April 1970 which declared Qatar an independent Arab Islamic state with the Sharia as its basic law. Khalifa bin Hamad was appointed prime minister in May. The first Council of Ministers was sworn in on 1 January 1970 and seven of its ten members were Al Thani. Khalifa bin Hamad's argument prevailed with regard to the federation proposal.[1]

Independence (1971–presence)

Qatar declared its independence on 1 September 1971 and became an independent state on 3 September. When Ahmad bin Ali issued the formal announcement from his Swiss villa instead of from his palace in Doha, many Qataris were convinced that it was time for a change in leadership. On 22 February 1972, Khalifa bin Hamad deposed Ahmad bin Ali when he was on a hunting trip in Iran. Khalifa bin Hamad had the tacit support of the Al Thani and Britain and also had the political, financial and military support of Saudi Arabia.[1]

In contrast to his predecessor's policies, Khalifa bin Hamad cut family allowances and increased spending on social programs, including housing, health, education, and pensions. In addition, he filled many top government posts with close relatives.[1] In 1993, Khalifa bin Hamad remained the Emir, but his son, Hamad bin Khalifa, the heir apparent and minister of defense, had taken over much of the day-to-day running of the country. The two consulted with each other on all matters of importance.[1]

In 1991, Qatar played a significant role in the Gulf War, particularly during the Battle of Khafji in which Qatari tanks rolled through the streets of the town and provided fire support for Saudi Arabian National Guard units which were engaging Iraqi Army troops.[128] Qatar allowed coalition troops from Canada to use the country as an airbase to launch aircraft on CAP duty, and also permitted air forces from the United States and France to operate in its territories.[1]

On 27 June 1995, deputy emir Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa deposed his father Khalifa in a bloodless coup. An unsuccessful counter-coup was staged in 1996. The emir and his father are now reconciled, although some supporters of the counter-coup remain in prison. The emir announced his intention for Qatar to move toward democracy and permitted more liberal press and municipal elections as a precursor to expected parliamentary elections. A new constitution was approved via public referendum in April 2003 and came into effect in June 2005.[7] Economic, social, and democratic reforms occurred in the proceeding years. In 2003, a woman was appointed to the cabinet as minister of education.

Qatar and Bahrain have had disputes over the ownership of Hawar Islands since the mid-20th century.[129] In 2001, the International Court of Justice awarded Bahrain sovereignty over Hawar Islands while allotting Qatar sovereignty over smaller disputed islands and the Zubarah region in mainland Qatar.[130] During the trial, Qatar provided the court with 82 forged documents to substantiate their claims of sovereignty over the territories in question. These claims were withdrawn at a later stage after Bahrain discovered the forgeries.[131]

In 2003, Qatar served as the US Central Command headquarters and one of the main launching sites of the invasion of Iraq.[132] In March 2005, a suicide bombing killed a British teacher at the Doha Players Theatre, shocking the country, which had not previously experienced acts of terrorism. The bombing was carried out by Omar Ahmed Abdullah Ali, an Egyptian resident in Qatar who had suspected ties to Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.[133][134] In June 2013, Sheikh Hamad Bin Khalifa stepped down as emir and transferred leadership to his son and heir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani.[135]

As a means to manage the revenue gained from LNG sales, the Qatar Investment Authority was established in 2005.[136] In 2008, the government launched Qatar National Vision 2030, which provides a framework for Qatar's long-term development as well as identifying threats and solutions.[137]

Arab Spring and military involvements (2010–)

Qatar played a role in the revolutionary wave of demonstrations, protests and civil wars in the Arab world collectively known as the Arab Spring. Having shifted from its traditional diplomatic role as a mediator, Qatar moved to support several transitional states and upheavals in the Middle East and North Africa.[138]

During the initial months of the Arab Spring, the country's most extensive media network, Al Jazeera, helped mobilize Arab support and shaped the narratives of protests and demonstrations.[139] Qatar sent hundreds of ground troops to support the National Transitional Council during the 2011 Libyan Civil War.[140] The troops were primarily military advisers,[141] and were sometimes labelled as "mercenaries" by the media.[142] Qatar also participated in the aerial campaign alongside several other coalition members.[143]

Qatar has taken a proactive role in the Syrian Civil War, which began in Spring of 2011.[139] In 2012, Qatar announced they would begin arming and bankrolling the opposition.[144] It was further reported that Qatar had funded the Syrian rebellion by "as much as $3 billion" over the first two years of the civil war.[145]

Beginning in 2015, Qatar has participated in the Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen against the Houthis and forces loyal to former President Ali Abdullah Saleh, who was deposed in the aftermath of the Arab Spring uprisings.[146]

Diplomatic crises (2014–)

In March 2014, in protest of Qatar's alleged involvement in financing factions and political parties in ongoing Middle Eastern conflicts, Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Bahrain recalled their ambassadors to Qatar.[147] The three countries returned their ambassadors in November of that year after an agreement was reached.[148]

On 5 June 2017, a number of countries led by Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain and Egypt (collectively referred to as the 'Quartet') severed ties with Qatar and enacted several punitive measures, such as closing air, land and sea borders to Qatar. Saudi Arabia also halted Qatari involvement in the ongoing war in Yemen.[149] The Quartet justified their actions by alluding to alleged Qatari ties to 'terrorist groups' in the region.[150]

See also

- History of Asia

- History of the Middle East

- List of emirs of Qatar

- List of wars involving Qatar

- Politics of Qatar

References

- Toth, Anthony. "Qatar: Historical Background." A Country Study: Qatar (Helen Chapin Metz, editor). Library of Congress Federal Research Division (January 19693). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Khalifa, Haya; Rice, Michael (1986). Bahrain Through the Ages: The Archaeology. Routledge. pp. 79, 215. ISBN 978-0710301123.

- "History of Qatar". Amiri Diwan. Archived from the original on 22 January 2008.

- Page, Kogan (2004). Middle East Review 2003-04: The Economic and Business Report. Kogan Page Ltd. p. 169. ISBN 978-0749440664.

- Qatar Country Study Guide Volume 1 Strategic Information and Developments. Int'l Business Publications, USA. 2012. pp. 34, 58. ISBN 978-0739762141.

- Rahman 2006, pp. 138–139

- "Background Note: Qatar". U.S. Department of State (June 2008). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Smith, Philip E. L. (28 October 2009). "Book reviews". American Anthropologist. 72 (3): 700–701. doi:10.1525/aa.1970.72.3.02a00790.

- Jeanna Bryner (9 December 2010). "Lost Civilization May Have Existed Beneath the Persian Gulf". Live Science. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- Abdul Nayeem, Muhammad (1998). Qatar Prehistory and Protohistory from the Most Ancient Times (Ca. 1,000,000 to End of B.C. Era). Hyderabad Publishers. p. 14. ISBN 9788185492049.

- Magee, Peter (2014). The Archaeology of Prehistoric Arabia. Cambridge Press. pp. 50, 178. ISBN 9780521862318.

- "History of Qatar" (PDF). www.qatarembassy.or.th. Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Qatar. London: Stacey International, 2000. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- Rice, Michael (1994). Archaeology of the Arabian Gulf. Routledge. pp. 206, 232–233. ISBN 978-0415032681.

- Masry, Abdullah (1997). Prehistory in Northeastern Arabia: The Problem of Interregional Interaction. Routledge. p. 94. ISBN 978-0710305367.

- Casey & Vine 1991, p. 12

- McCoy, Lisa (2014). Qatar (Major Muslim Nations). Mason Crest. ISBN 9781633559851.

- Mohamed Althani, p. 15

- Peoples of Western Asia. Marshall Cavendish Corporation. 2007. p. 351. ISBN 978-0761476825.

- Carter, Robert Jr.; Killick, Robert (2014). Al-Khor Island: Investigating Coastal Exploitation in Bronze Age Qatar (PDF). Moonrise Press Ltd. p. 43. ISBN 978-1910169001.

- Sterman, Baruch (2012). Rarest Blue: The Remarkable Story Of An Ancient Color Lost To History And Rediscovered. Lyons Press. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0762782222.

- Carter, Killick (2014). p. 45.

- "Late Babylonian Period and Neo-Assyrian Period (1000 BC - 606 BC)". anciv.info. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- Liverani, Mario (2014). The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy. Routledge. p. 518. ISBN 978-0415679060.

- Casey & Vine 1991, p. 16

- Sultan Muhesen & Faisal Al Naimi (June 2014). "Archaeological heritage of pre-Islamic Qatar" (PDF). World Heritage. 72: 50. Retrieved 14 February 2016.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Gulf States: Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, United Arab Emirates, Oman, Yemen. JPM Publications. 2010. p. 31. ISBN 978-2884520997.

- Althani, Mohamed (2013). Jassim the Leader: Founder of Qatar. Profile Books. p. 16. ISBN 978-1781250709.

- Reade, Julian (1996). Indian Ocean In Antiquity. Routledge. p. 252. ISBN 978-0710304353.

- Kapel, Holger (1967). Atlas of the stone-age cultures of Qatar. p. 12.

- Casey & Vine 1991, p. 17

- Cadène, Philippe (2013). Atlas of the Gulf States. BRILL. p. 10. ISBN 978-9004245600.

- "New techniques to locate lost prehistory in Qatar". world-archaeology.com. 28 March 2013.

- Rahman 2006, pp. 33

- "Maps". Qatar National Library. Archived from the original on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- "Qatar - Early history". globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- Gillman, Ian; Klimkeit, Hans-Joachim (1999). Christians in Asia Before 1500. University of Michigan Press. pp. 87, 121. ISBN 978-0472110407.

- Commins, David (2012). The Gulf States: A Modern History. I. B. Tauris. p. 16. ISBN 978-1848852785.

- "AUB academics awarded $850,000 grant for project on the Syriac writers of Qatar in the 7th century AD" (PDF). American University of Beirut. 31 May 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2015. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- PROCEEDINGS OF THE DOMESTIC AND FOREIGN MISSIONARY SOCIETY OF THE PROTESTANT EPISCOPA; CHURCH IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, AT MEETING HELD IN PHILADELPHIA IN AUGUST AND SEPT. 1835, p. 65

- Kozah, Mario; Abu-Husayn, Abdulrahim; Al-Murikhi, Saif Shaheen (2014). The Syriac Writers of Qatar in the Seventh Century. Gorgias Press LLC. p. 24. ISBN 978-1463203559.

- "Christianity in the Gulf during the first centuries of Islam" (PDF). Oxford Brookes University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2015. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- Rahman 2006, pp. 34

- Fromherz, Allen (13 April 2012). Qatar: A Modern History. Georgetown University Press. pp. 43, 60, 2041. ISBN 978-1-58901-910-2.

- O'Mahony, Anthony; Loosley, Emma (2010). Eastern Christianity in the Modern Middle East (Culture and Civilization in the Middle East). Routledge. p. 23. ISBN 978-0415548038.

- A political chronology of the Middle East. Routledge / Europa Publications. 2001. p. 192. ISBN 978-1857431155.

- Lo, Mbaye (2009). Understanding Muslim Discourse: Language, Tradition, and the Message of Bin Laden. University Press of America. p. 56. ISBN 978-0761847489.

- Gaiser, Adam R (2010). "What do we learn about the early Kharijites and Ibadiyya from their coins?". The Journal of the American Oriental Society. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Sanbol, Amira (2012). Gulf Women. Bloomsbury UK. p. 42. ISBN 978-1780930435.

- al-Aqlām. 1. Wizārat al-Thaqāfah wa-al-Irshād.

وذكر في وفيات الاعيان لابن خنكان ابو نعامة قطري بن الفجاءة واسمه جعونة ين مازن بن يزيد اين زياد ين حبتر بن مالك ين عمرو رين تهيم بن مر التميمي الثسيباني ولد في الجنوب الشرقي من قرية الخوير شمال قطر في

- Baum, Wilhelm; Winkler, Dietmar W. (2010). The Church of the East: A Concise History. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415600217.

- Paul Rivlin, Arab Economies in the Twenty-First Century, p. 86. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009. ISBN 9780521895002

- Casey & Vine 1991, p. 18

- Qatar, 2012 (The Report: Qatar). Oxford Business Group. 2012. p. 233. ISBN 978-1907065682.

- Russell, Malcolm (2014). The Middle East and South Asia 2014. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 151. ISBN 978-1475812350.

- Mohamed Althani, p. 17

- Al-Tabari, Abu Ja'far Muhammad ibn Jarir. The History of al-Tabari, Volume XXXVI: The Revolt of the Zanj. Trans. David Waines. Ed. Ehsan Yar-Shater. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1992. ISBN 0-7914-0764-0. p. 31

- Zizek, Slavoj (2009). First as Tragedy, Then as Farce. Verso. p. 121. ISBN 978-1844674282.

- Saunders, John Joseph (1978). A History of Medieval Islam. Routledge. p. 130.

- "History". qatarembassy.net. Archived from the original on 17 February 2015. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- Larsen, Curtis (1984). Life and Land Use on the Bahrain Islands: The Geoarchaeology of an Ancient Society (Prehistoric Archeology and Ecology series). University of Chicago Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0226469065.

- Olson, James S. (1991). Historical Dictionary of European Imperialism. Greenwood. p. 289. ISBN 978-0313262579.

- Gillespie, Carol Ann (2002). Bahrain (Modern World Nations). Chelsea House Publications. p. 31. ISBN 978-0791067796.

- Orr, Tamra (2008). Qatar (Cultures of the World). Cavendish Square Publishing. p. 18. ISBN 978-0761425663.

- Anscombe, Frederick (1997). The Ottoman Gulf: The Creation of Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar. Columbia University Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0231108393.

- Leonard, Thomas (2005). Encyclopedia of the Developing World. Routledge. p. 133. ISBN 978-1579583880.

- Potter, Lawrence (2010). The Persian Gulf in History. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 262. ISBN 978-0230612822.

- Ownership's Document of a Palm Garden in Island of Sitra, Bahrain belonging to Shaikh Salama Bin Saif in which the owner carries the Al-Utbi last name dated 1699 - 1111 Hijri, http://www.jasblog.com/wp/upload/e0dc2f375e58_11E3C/_____12_thumb.jpg , http://www.jasblog.com/wp/upload/e0dc2f375e58_11E3C/_____11_thumb.jpg , see also Ownership's Document of a Palm Garden in Island of Nabih Saleh, Bahrain belonging to Shaikh Mohamed Bin Derbas in which the owner carries the Al-Utbi last name dated 1804 - 1219 Hijri, http://www.jasblog.com/wp/upload/e0dc2f375e58_11E3C/_____21_thumb.jpg , http://www.jasblog.com/wp/upload/e0dc2f375e58_11E3C/996.jpg , http://www.jasblog.com/wp/upload/e0dc2f375e58_11E3C/_____22.jpg , also in the Precis Of Turkish Expansion On The Arab Littoral Of The Persian Gulf And Hasa And Katif Affairs. By J. A. Saldana; 1904, I.o. R R/15/1/724, assertion by British Foreign Secretary Of State in 1871 that Isa Bin Tarif belongs to the Original Uttoobee's who conquered Bahrain, which means that he differentiates the Original Uttoobee's whose descendants are the Al Bin Ali since they are the oldest tribe who officially carried the Al-Utbi last name in their ownership's documents, from the Uttoobees who entered under its umbrella such as the Al-Khalifa and Al-Sabah and other families

- Alghanim, Salwa (1998). The Reign of Mubarak-Al-Sabah: Shaikh of Kuwait 1896-1915. I. B. Tauris. p. 6. ISBN 978-1860643507.

- Heard-Bey, Frauke (2008). From Tribe to State. The Transformation of Political Structure in Five States of the GCC. p. 39. ISBN 978-88-8311-602-5.

- 'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol I. Historical. Part IA & IB. J G Lorimer. 1915' [1000] (1155/1782), p. 1001

- Crystal, Jill (1995). Oil and Politics in the Gulf: Rulers and Merchants in Kuwait and Qatar. Cambridge University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0521466356.

- "Qatar". worldatlas.com. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- Hasan, Mohibbul (2005). Waqai-I Manazil-I Rum; Tipu Sultan's Mission to Constantinople. AAKAR BOOKS. p. 17. ISBN 978-8187879565.

- "'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol I. Historical. Part IA & IB. J G Lorimer. 1915' [839] (994/1782)". qdl.qa. 30 September 2014. p. 840. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- "'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol I. Historical. Part IA & IB. J G Lorimer. 1915' [840] (995/1782)". qdl.qa. 30 September 2014. p. 840. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- "'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol I. Historical. Part IA & IB. J G Lorimer. 1915' [789] (944/1782)". qdl.qa. 30 September 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- Casey & Vine 1991, p. 29

- Rahman 2006, p. 53

- "Arabia, Yemen, and Iraq 1700-1950". san.beck.org. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- Rahman 2006, p. 54

- Casey, Michael S. (2007). The History of Kuwait (The Greenwood Histories of the Modern Nations). Greenwood. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-0313340734.

- "'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol I. Historical. Part IA & IB. J G Lorimer. 1915' [843] (998/1782)". qdl.qa. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- Rahman 2006, pp. 35–37

- "'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol I. Historical. Part IA & IB. J G Lorimer. 1915' [793] (948/1782)". qdl.qa. 30 September 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- Rahman 2006, pp. 37

- "'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol I. Historical. Part IA & IB. J G Lorimer. 1915' [794] (949/1782)". qdl.qa. 30 September 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- "'Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf. Vol I. Historical. Part IA & IB. J G Lorimer. 1915' [795] (950/1782)". qdl.qa. 30 September 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- Rahman 2006, p. 97

- Rahman 2006, p. 98

- Rahman 2006, p. 109

- Rahman 2006, pp. 110–113

- Rahman 2006, pp. 113–115

- Rahman 2006, p. 118

- Rahman 2006, pp. 115–116

- Rahman 2006, p. 116

- Rahman 2006, p. 117

- Rahman 2006, p. 119

- "'A collection of treaties, engagements and sanads relating to India and neighbouring countries [...] Vol XI containing the treaties, & c., relating to Aden and the south western coast of Arabia, the Arab principalities in the Persian Gulf, Muscat (Oman), Baluchistan and the North-West Frontier Province' [113v] (235/822)". Qatar Digital Library. 9 October 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- "'File 19/243 IV Zubarah' [8r] (15/322)". Qatar Digital Library. 21 March 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- Rahman 2006, pp. 120

- Rahman 2006, pp. 123

- Rahman 2006, p. 140

- "'Persian Gulf Gazetteer, Part I Historical and Political Materials, Précis of Bahrein Affairs, 1854-1904' [35] (54/204)". qdl.qa. 4 April 2014. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- "'Persian Gulf Gazetteer, Part I Historical and Political Materials, Précis of Bahrein Affairs, 1854-1904' [36] (55/204)". qdl.qa. 4 April 2014. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- Rahman 2006, pp. 141–142

- Rahman 2006, pp. 142–143

- Rahman 2006, pp. 143–144

- Fromherz, Allen (13 April 2012). Qatar: A Modern History. Georgetown University Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-58901-910-2.

- Rahman 2006, pp. 152

- "Battle of Al Wajbah". Qatar Visitor. 2 June 2007. Archived from the original on 17 January 2013. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- "'Field notes. Mesopotamia' [95r] (194/230)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 14 January 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- "'Field notes. Mesopotamia' [95v] (195/230)". Qatar Digital Library. Retrieved 14 January 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- H.R.P. Dickson to the Political Resident, Bahrain, 4 July 1933, British Library India Office Records (IOR) PS/12/2/213-0

- Report of G.M. Lees of 21 March 1926, BP Archive, Warwick University, Archive reference 135500.

- Diary of a Visit to Qatar, C.C. Mylles, BP Archive, Warwick University, Archive Reference 135500.

- "The Qatar Oil Discoveries" by Rasoul Sorkhabi". geoxpro.com. 2010. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- Herb, Michael (2014). The Wages of Oil: Parliaments and Economic Development in Kuwait and the UAE. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0801453366.

- Shahdad, Ibrahim. "الحراك الشعبيفيقطر 1950–1963 دراسة تحليلية (Popular movements 1950–1963, analytic study)" (PDF). gulfpolicies.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- "About Ministry of Interior". Qatar Ministry of Interior. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- Halliday, Fred (2001). Arabia Without Sultans. Saqi Books. ISBN 978-0863563812.

- "الدراسة الجامعية في مصر و حركة 1963 في قطر (University of Egypt and 1963 movement in Qatar)" (PDF) (in Arabic). dr-alkuwari.net. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- Kadhim, Abbas (2013). Governance in the Middle East and North Africa: A Handbook. Routledge. p. 258. ISBN 978-1857435849.

- Hiro, Dilip (2014). Inside the Middle East. Routledge. p. 15. ISBN 978-0415835084.

- Zahlan 1979, p. 102

- Zahlan 1979, p. 104

- Zahlan 1979, p. 105

- Zahlan 1979, p. 106

- "Saudi Town Reclaimed". Washington Post. 1 February 1991. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- Guo, Rongxing (2007). Territorial Disputes and Resource Management: A Global Handbook. Nova Science Pub Inc. p. 149. ISBN 978-1600214455.

- "Maritime Delimitation and Territorial Questions between Qatar and Bahrain (Qatar v. Bahrain)". International Court of Justice. 16 March 2001. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- "Maritime Delimitation and Territorial Questions between Qatar and Bahrain (Qatar v. Bahrain)" (PDF). International Court of Justice. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- "Qatar (01/10)". State.gov. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- Coman, Julian (21 March 2005). "Egyptian Suicide Bomber Blamed for Attack in Qatar". The Independent.

- Analytica, Oxford (25 March 2005). "The Advent of Terrorism in Qatar". Forbes.

- "Profile: Qatar Emir, Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani". bbc.com. 25 June 2013. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- Mohammed Sergie (11 January 2017). "The Tiny Gulf Country With a $335 Billion Global Empire". Bloomberg. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- "Qatar National Vision 2030". Amiri Diwan of the State of Qatar. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- Guido Steinberg (7 February 2012). "Qatar and the Arab Spring" (PDF). German Institute for International and Security Affairs. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- Kristian Coates Ulrichsen (24 September 2014). "Qatar and the Arab Spring: Policy Drivers and Regional Implications". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- Black, Ian (26 October 2011). "Qatar admits sending hundreds of troops to support Libya rebels". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- Walker, Portia (13 May 2011). "Qatari military advisers on the ground, helping Libyan rebels get into shape". The Washington Post.

- aira (31 December 2011). "Qatar Creates Anti-Syria Mercenary Force based in Turkey". Turkishnews.com. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- "Qatar, several EU states up for Libya action: diplomat". EU Business. 19 March 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- DeYoung, Karen (2 March 2012). "Saudi, Qatari plans to arm Syrian rebels risk overtaking cautious approach favored by U.S". The Washington Post. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- Roula Khalaf and Abigail Fielding Smith (16 May 2013). "Qatar bankrolls Syrian revolt with cash and arms". Financial Times. Retrieved 3 June 2013. (subscription required)

- "Saudi-led coalition strikes rebels in Yemen, inflaming tensions in region". CNN. 27 March 2015.

- "Saudi Arabia, UAE, Bahrain withdraw envoys from Qatar". CNN. 5 March 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- "Saudi Arabia, UAE and Bahrain end rift with Qatar, return ambassadors". Reuters. 16 November 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- "Gulf rift deepens: Saudi suspends Qatar troops' involvement in Yemen war". Business Standard India. Business Standard. 5 June 2017. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- "Four countries cut links with Qatar over 'terrorism' support". BBC News. 5 June 2017. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

Bibliography

- Rahman, Habibur (2006). The Emergence Of Qatar. Routledge. ISBN 978-0710312136.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Casey, Paula; Vine, Peter (1991). The heritage of Qatar (print ed.). Immel Publishing. ISBN 978-0907151500.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zahlan, Rosemarie Said (1979). The creation of Qatar (print ed.). Barnes & Noble Books. ISBN 978-0064979658.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Qatar Digital Library - an online portal providing access to previously undigitised British Library archive materials relating to Gulf history and Arabic science

- The History of Qatar - Qatar Visitor

- The History of Qatar - ILoveQatar.net