Laura Wheeler Waring

Laura Wheeler Waring (May 16, 1887 – February 3, 1948) was an American artist and educator, best known for her paintings of prominent African Americans that she made during the Harlem Renaissance.[1] She taught art for more than 30 years at Cheyney University in Pennsylvania.[2]

Laura Wheeler Waring | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | May 16, 1887 |

| Died | February 3, 1948 (aged 60) |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Painter |

| Spouse(s) | Walter E. Waring |

Early life

Laura Wheeler was born on May 16, 1887, in Hartford, Connecticut, the fourth child of six, to Mary (née Freeman) and Reverend Robert Foster Wheeler. Her mother was a daughter of Amos Noë Freeman, a Presbyterian minister, and Christiana Williams Freeman, who had been prominent in anti-slavery activities, including the Underground Railroad in Portland, Maine and Brooklyn, New York.[3]

In 1906, Waring began teaching part-time in Philadelphia at Cheyney Training School for Teachers (later renamed Cheyney State Teachers College and now known as Cheyney University.) She taught art and music at Cheyney until 1914 when she traveled abroad to Europe. Her occupation at Cheyney was time-consuming, as it was a boarding school and she was often needed to work evenings and Sundays. This left her without much time to practice art. 1906–1914 were slow years for her artistic career as a result of this. Waring worked long hours teaching art, sometimes spending summers teaching drawing at Harvard and Columbia for additional money.

After she returned from Europe, she continued to work at Cheyney and did so for more than thirty years. In her later years at Cheyney, she was the director of the art programs. In 1914 Laura Wheeler-Waring was granted a trip to Europe by the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts’ William E. Cresson Memorial Scholarship. She studied at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière in Paris, France and traveled throughout Great Britain. While living in Paris, Wheeler-Waring frequented the Jardin du Luxembourg. She painted Le Parc Du Luxembourg (1918), oil on canvas, based on a sketch she made during one of her recurrent visits. Wheeler-Waring also spent much time in the Louvre Museum studying Monet, Manet, Corot and Cézanne. "I thought again and again how little of the beauty of really great pictures is revealed in the reproductions which we see and how freely and with what ease the great masters paint."[4]

Wheeler-Waring planned on traveling more to Switzerland, Italy, Germany and the Netherlands, but her trip was cut short when war was declared in Europe. After being in Europe for three months, she was required to return to the United States. Waring's trip at the time had very little effect on her career, but it has been remarked as a major influence on her and her work as an artist. Receiving the scholarship gave her the time to evolve as an artist and, as the award was highly regarded, she also gained publicity by it.[4]

Education

Laura graduated from Hartford Public High School in 1906 and studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, graduating in 1914.[2]

Time in Paris (1924–1925)

After the end of the war, Waring returned to Paris in June 1924. Her second trip to Paris was regarded to be a turning point in her style as well as her career. Waring described this time as the most purely art-motivated period in her life, the "only period of uninterrupted life as an artist with an environment and associates that were a constant stimulus and inspiration."[5] For approximately four months, Waring lived in France, absorbing French culture and lifestyle. She began to paint many portraits, and in October enrolled to study at the Académie de la Grande Chaumiére, where she studied painting. Instead of soft, pastel tones she painted a more vibrant and realistic method. Houses at Semur, France (1925), oil on canvas, has been noted by art historians the painting that marked Waring's change in style. Her use of vivid color, light, and atmosphere in this work is characteristic of the style she established after this trip to Europe and which she continued throughout her career.

Besides a posthumous exhibition at Howard University in 1949, Waring's paintings made in Paris are not believed to have been exhibited and their whereabouts are unknown. In addition to painting, Waring wrote and illustrated a short story with close friend and novelist, Jessie Redmon Fauset. Fauset accompanied Waring throughout her travels in France at this time. Waring wrote the short story, "Dark Algiers and White," for The Crisis magazine of the NAACP, and it was later published.[4]

Personal life

Laura Wheeler married Walter Waring on June 23, 1927. He was from Philadelphia and worked in the public school system as a teacher. When they first married, money was scarce, so they delayed their honeymoon for two years. In 1929, the newlyweds traveled to France, spending more than two months there. They had no children.[4]

Art career

Waring was among the artists displayed in the country's first exhibition of African-American art, held in 1927 by the William E. Harmon Foundation.[6] She was commissioned by the Harmon Foundation to do portraits of prominent African Americans and chose some associated with the Harlem Renaissance.[6] Her work was soon displayed in American institutions, including the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, DC, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art.[7] She currently has portraits in the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery.

Death

Wheeler-Waring died on February 3, 1948, in her Philadelphia home after a long illness.[7] A year later, Howard University Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. held an exhibition of art in her honor.[8]

Works

Selected portraits

|

|

|

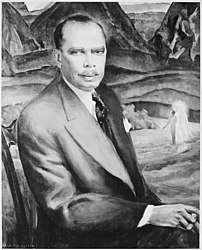

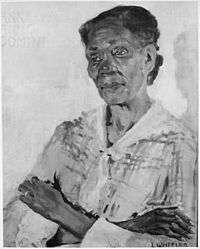

| W. E. B. Du Bois | James Weldon Johnson | Anna Washington Derry |

Further reading

- Rosenfeld, Michael (2008). African American art : 200 years : 40 distinctive voices reveal the breadth of nineteenth and twentieth century art. New York, NY: Michael Rosenfeld Gallery. ISBN 9781930416437. OCLC 226235431.

- Farrington, Lisa E. (2011). Creating their own image : the history of African-American women artists (paperback ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199767601. OCLC 712600445.

References

- Bontemps, Arna Alexander; Fonvielle-Bontemps, Jacqueline (Spring 1987). "African-American Women Artists: An Historical Perspective". Sage: A Scholarly Journal on Black Women. 4 (1): 17–24. ISBN 9780815322184.

- "Laura Wheeler Waring". Connecticut Women's Hall of Fame.

- "Abyssinian Congregational Church". Congregational Library & Archives. Retrieved May 5, 2019.

- Leininger-Miller, Theresa (Summer 2005). "'A Constant Stimulus and Inspiration': Laura Wheeler Waring in Paris in the 1910s and 1920s". Source: Notes in the History of Art. 24 (4): 13–23. doi:10.1086/sou.24.4.23207946. JSTOR 23207946.

- Kirschke, Amy Helene (August 4, 2014). Women Artists of the Harlem Renaissance. University Press of Mississippi. p. 77. ISBN 9781626742079.

- Art and Culture: Exploring Freedom/Laura Wheeler Waring, African American World, PBS-WNET

- Mennenga, Lacinda (May 30, 2008), "Laura Wheeler Waring (1887–1948)", Black Past.org, accessed January 28, 2014.

- "Laura Wheeler Waring | American artist". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- "Anna Washington Derry by Laura Wheeler Waring / American Art". americanart.si.edu.

- Thomas, Alma; Fort Wayne Museum of Art (1998). Alma W. Thomas: A Retrospective of the Paintings. Pomegranate. pp. 22. ISBN 9780764906862.

External links

- Laura Wheeler Waring at the Connecticut Women's Hall of Fame

- Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery

- Article about Waring at the African American Print & Visual Media at the Nat'l Archives