Espada Cemetery

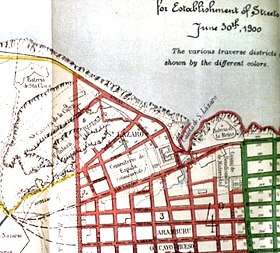

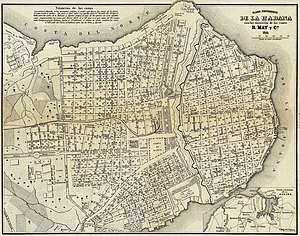

The Espada Cemetery was located in the Barrio of San Lazaro approximately a mile west of the city walls, near the cove of Juan Guillen and close to the San Lázaro Leper Hospital.[1] In use from 1806 to 1878, the Espada Cemetery was the first public burial place designed and constructed in Havana; prior to the cemetery, the Havana custom had been to bury the dead in the vaults of the churches such as Iglesia del Espíritu Santo in Havava Vieja.[1] It was named after the Bishop incumbent at the time of design, José Díaz de Espada y Landa.[1] Its boundaries included the present streets of San Lázaro, Vapor, Espada, and Aramburu. Despite being officially called Campo Santo, the people of Havana referred to the cemetery as el Cementerio de Espada. The cemetery was closed in 1878 and demolished in 1908, only a small wall remains of the original structure.[2]

| Details | |

|---|---|

| Established | 1806 |

| Location | Havana |

| Country | Cuba |

| Coordinates | 23°08′27″N 82°22′31″W |

| Type | Public |

Location

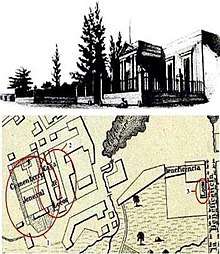

The site of Espada Cemetery was between present-day Calle Espada to the east and Calles Vapor and San Lazaro. The main cemetery entrance was on Calle San Lazaro, most of the funeral processions went down Calle San Lazaro. The Hospital de San Lazaro had its entrance pediment facing present day Calle Marina, the area was the edge of the city originally known as Barrio San Lazaro. The Torreón de San Lázaro built in 1655 is located at the intersections of Calles Vaor and Marina. The San Dionisio hospital, created by the initiative of Captain General Francisco Dionisio Vives and by Bishop Espada, was exclusively for mentally ill men and located between the hospital of San Lazaro and the General Cemetery. In the same area was also a room of the Real Casa de Beneficencia, intended exclusively for demented women, but this had its front to Calle Belascoaín. The quarry of San Lazaro where Jose Marti had been imprisoned in 1870, was to the east. In front of the Casa de Beneficencia was the Bateria de la Reina which was named after the Count of Santa Clara, Juan Procopio Bassecourt, governor of Cuba, who built the battery between 1797 and 1799.

Design

The Espada cemetery was a garden type, a single wall 2.5 meters thick which contained the crypts. The design and construction were directed by an architect with the surname of Aulet. The cemetery had a central courtyard, the walls were approximately 6 meters tall (4 crypts) with an elaborate stone coping for protection from the elements. The paintings that adorned the building entrance pavilion were by the Venetian Giuseppe Perovani (1765-1835). The cemetery was officially inaugurated on February 2, 1806. Only a small section of the original wall remains.

History

.

The cemetery was built in response to population growth around the area, and the resulting scarcity of church land that could be used for burial.[3] It was proposed and sanctioned by the government of Don Salvador de Muro y Salazar in 1804, and, after two years of design and construction, the cemetery was ready for use in 1806, and was inaugurated on February 2 of that year.[3]

The cemetery was used as the primary burial ground for the city of Havana from 1806 until the late 1860s. In 1868, a cholera epidemic broke out in the area, resulting in a greatly increased rate of death.[4] It soon became apparent that the Espada Cemetery, still the only major burial ground in the region, would not suffice to handle the number of deaths that were coming from the epidemic.[4] To compound matters, the reformist El Siglo scorned the Espada Cemetery in an 1865 editorial as unworthy of "the most miserable village."[4] One United States visitor, after returning from a sobering tour of Havana's Espada cemetery at that time, instructed his hotel's attendant that if he were to die on the island, he must be buried at sea.[5] In order to supplement the struggling Espada Cemetery, another cemetery, the Colón Cemetery (Spanish: Cementerio de Cristóbal Colón), named for explorer Christopher Columbus, was inaugurated in 1871. In 1878, the Espada Cemetery was closed in favour of the larger Colón Cemetery and because of the lack of space still remaining within the Espada Cemetery grounds. The Colón Cemetery remains in active use today, and now harbours more than 800,000 corpses.

Notes

- Reynolds, Charles B. (1905) Standard Guide to Cuba: A New and Complete Guide to the Island of Cuba Pp. 70+; Publisher: Foster & Reynolds Co.

- "Cementerio de Espada". Retrieved 2018-12-16.

- Lightfoot, Claudia. (February 6, 2002) Havana: A Cultural and Literary Companion, page 181. Signal Books. ISBN 1-902669-32-0.

- Martinez-Fernandez, Luis. (2002) Protestantism and Political Conflict in the Nineteenth-Century Hispanic Caribbean., pages 40+. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-2994-8.

- Martinez-Fernandez, Luiz. (April 1, 2000) Journal of Ecclesiastical History Crypto-Protestants and Pseudo-Catholics in the Nineteenth-Century Hispanic Caribbean. Volume 51; Issue 2; Page 347 (citing to "Blythe to Cass, 20 July 1857, NA, despatches from US consuls in Havana, microfilm roll T20, vol. 36; George W. Williams, Sketches of travel in the old and new world, Charleston, SC 1871, 55; Richard Henry Dana, Jr, To Cuba and back: a vacation voyage, ed. C. Harvey Gardiner, Carbondale, IL 1966, 102-3.")

References

- "The Espada Cemetery / El Cementerio de Espada". Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 5 June 2008.

- Gerald, Andrew (2000). Architectural Heritage of the Caribbean: An A-Z of Historic Buildings. Signal Books. ISBN 1-902669-08-8.

- Cova, Antonio Rafael De la; Antonio Rafael Cova (2003). Cuban Confederate Colonel: The Life of Ambrosio Jose Gonzales. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 1-57003-496-6.