La Cabaña

Fortaleza de San Carlos de la Cabaña (Fort of Saint Charles), colloquially known as La Cabaña, is an 18th-century fortress complex, the third-largest in the Americas, located on the elevated eastern side of the harbor entrance in Havana, Cuba. The fort rises above the 200-foot (60 m) hilltop, along with Morro Castle.

History

After the capture of Havana by British forces in 1762, an exchange was soon made to return Havana to the Spanish, the controlling colonial power of Cuba, in exchange for Florida. A key factor in the British capture of Havana turned out to be the overland vulnerability of El Morro. This realization and the fear of further attacks following British colonial conquests in the Seven Years War prompted the Spanish to build a new fortress to improve the overland defense of Havana; King Carlos III of Spain began the construction of La Cabaña in 1763. Replacing earlier and less extensive fortifications next to the 16th-century El Morro fortress, La Cabaña was the second-largest colonial military installation in the New World by the time it was completed in 1774 (after the St. Felipe de Barajas fortification at Cartagena, Colombia), at great expense to Spain.

Over the next two hundred years the fortress served as a base for both Spain and later independent Cuba – La Cabaña has been used as a prison by the government of Fidel Castro and his younger brother Raúl.

1959

In January 1959, the revolutionary group led by Fidel Castro seized La Cabaña; the defending Cuban Army unit offered no resistance and surrendered. Che Guevara used the fortress as a headquarters and military prison for several months. During his five-month tenure in that post (January 2 through June 12, 1959), Guevara oversaw the revolutionary tribunals and executions of people who had opposed the communist revolution, including former members of Buró de Represión de Actividades Comunistas, Batista's secret police.[1] There were 176 executions by Che Guevara documented for La Cabaña Fortress prison during Che’s command (January 3 to November 26, 1959).[2]

La Cabaña, land reform, and literacy

The first major political crisis arose over what to do with the captured Batista officials who had perpetrated the worst of the repression.[3] During the rebellion against Batista's dictatorship, the general command of the rebel army, led by Fidel Castro, introduced into the territories under its control the 19th-century penal law commonly known as the Ley de la Sierra (Law of the Sierra).[4] This law included the death penalty for serious crimes, whether perpetrated by the Batista regime or by supporters of the revolution. In 1959 the revolutionary government extended its application to the whole of the republic and to those it considered war criminals, captured and tried after the revolution. According to the Cuban Ministry of Justice, this latter extension was supported by the majority of the population, and followed the same procedure as those in the Nuremberg trials held by the Allies after World War II.[5]

Revolutionary justice

To implement a portion of this plan, Castro named Guevara commander of the La Cabaña Fortress prison, for a five-month tenure (2 January through 12 June 1959).[6] Guevara was charged by the new government with purging the Batista army and consolidating victory by exacting "revolutionary justice" against those regarded as traitors, chivatos (informants) or war criminals.[7] As commander of La Cabaña, Guevara reviewed the appeals of those convicted during the revolutionary tribunal process.[8]

Tribunals

The tribunals were conducted by 2–3 army officers, an assessor, and a respected local citizen.[9] On some occasions the penalty delivered by the tribunal was death by firing-squad.[10] Raúl Gómez Treto, senior legal advisor to the Cuban Ministry of Justice, has argued that the death penalty was justified in order to prevent citizens themselves from taking justice into their own hands, as had happened twenty years earlier in the anti-Machado rebellion.[11] Biographers note that in January 1959 the Cuban public was in a "lynching mood",[12] and point to a survey at the time showing 93% public approval for the tribunal process.[8] Moreover, a 22 January 1959, Universal Newsreel broadcast in the United States and narrated by Ed Herlihy featured Fidel Castro asking an estimated one million Cubans whether they approved of the executions, and being met with a roaring "¡Si!" (yes).[13] With as many as 20,000 Cubans estimated to have been killed at the hands of Batista's collaborators,[14][15][16][17] and many of the accused war criminals sentenced to death accused of torture and physical atrocities,[8] the newly-empowered government carried out executions, punctuated by cries from the crowds of "¡al paredón!" ([to the] wall!),[3] which biographer Jorge Castañeda describes as "without respect for due process".[18]

—Jon Lee Anderson, author of Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, PBS forum[19]

Executions

Although accounts vary, it is estimated that several hundred people were executed nationwide during this time, with Guevara's jurisdictional death total at La Cabaña ranging from 55 to 105.[20] Conflicting views exist of Guevara's attitude towards the executions at La Cabaña. Some exiled opposition biographers report that he relished the rituals of the firing squad, and organized them with gusto, while others relate that Guevara pardoned as many prisoners as he could.[18] All sides acknowledge that Guevara had become a "hardened" man who had no qualms about the death penalty or about summary and collective trials.[2] If the only way to "defend the revolution was to execute its enemies, he would not be swayed by humanitarian or political arguments".[18] In a 5 February 1959, letter to Luis Paredes López in Buenos Aires Guevara states unequivocally: "The executions by firing squads are not only a necessity for the people of Cuba, but also an imposition of the people."[21]

Land redistribution

Along with ensuring "revolutionary justice", the other key early platform of Guevara was establishing agrarian land reform. Almost immediately after the success of the revolution, on 27 January 1959, Guevara made one of his most significant speeches where he talked about "the social ideas of the rebel army". During this speech he declared that the main concern of the new Cuban government was "the social justice that land redistribution brings about".[22] A few months later,n 17 May 1959, the Agrarian Reform Law, crafted by Guevara, went into effect, limiting the size of all farms to 1,000 acres (400 ha). Any holdings over these limits were expropriated by the government and either redistributed to peasants in 67-acre (270,000 m2) parcels or held as state-run communes.[23] The law also stipulated that foreigners could not own Cuban sugar-plantations.[24]

On 12 June 1959, Castro sent Guevara out on a three-month tour of 14 mostly Bandung Pact countries (Morocco, Sudan, Egypt, Syria, Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka, Burma, Thailand, Indonesia, Japan, Yugoslavia, Greece) and the cities of Singapore and Hong Kong.[25] Sending Guevara away from Havana allowed Castro to appear to distance himself from Guevara and his Marxist sympathies, which troubled both the United States and some of the members of Castro's 26 July Movement.[26] While in Jakarta, Guevara visited Indonesian president Sukarno to discuss the recent revolution of 1945-1949 in Indonesia and to establish trade relations between their two countries. The two men quickly bonded, as Sukarno was attracted to Guevara's energy and his relaxed informal approach; moreover they shared revolutionary leftist aspirations against western imperialism.[27] Guevara next spent 12 days in Japan (15–27 July), participating in negotiations aimed at expanding Cuba's trade relations with that country. During the visit he refused to visit and lay a wreath at Japan's Tomb of the Unknown Soldier commemorating soldiers lost during World War II, remarking that the Japanese "imperialists" had "killed millions of Asians".[28] Instead, Guevara stated that he would visit Hiroshima, where the American military had detonated an atom-bomb 14 years earlier.[28] Despite his denunciation of Imperial Japan, Guevara considered President Truman a "macabre clown" for the bombings,[29] and after visiting Hiroshima and its Peace Memorial Museum he sent back a postcard to Cuba stating, "In order to fight better for peace, one must look at Hiroshima."[30]

Upon Guevara's return to Cuba in September 1959, it became evident that Castro now had more political power. The government had begun land seizures in accordance with the agrarian reform law, but was hedging on compensation offers to landowners, instead offering low-interest "bonds", a step which put the United States on alert. At this point the affected wealthy cattlemen of Camagüey mounted a campaign against the land redistributions and enlisted the newly-disaffected rebel leader Huber Matos, who along with the anti-Communist wing of 26 July Movement, joined them in denouncing "Communist encroachment".[31] During this time Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo was offering assistance to the "Anti-Communist Legion of the Caribbean" which was training in the Dominican Republic. This multi-national force, composed mostly of Spaniards and Cubans, but also of Croatians, Germans, Greeks, and right-wing mercenaries, was plotting to topple Castro's new regime.[31]

La Coubre

Such threats were heightened when, on 4 March 1960, two massive explosions ripped through the French freighter La Coubre, which was carrying Belgian munitions from the port of Antwerp, and was docked in Havana Harbor. The blasts killed at least 76 people and injured several hundred, with Guevara personally providing first aid to some of the victims. Fidel Castro immediately accused the CIA of "an act of terrorism" and held a state funeral the following day for the victims of the blast.[32] At the memorial service Alberto Korda took the famous photograph of Guevara, now known as Guerrillero Heroico.[33]

INRA

Perceived threats prompted Castro to eliminate more "counter-revolutionaries" and to utilize Guevara to drastically increase the speed of land reform. To implement this plan, a new government agency, the National Institute of Agrarian Reform (INRA), was established by the Cuban Government to administer the new Agrarian Reform law. INRA quickly became the most important governing body in the nation, with Guevara serving as its head in his capacity as minister of industries.[24] Under Guevara's command, INRA established its own 100,000-person militia, used first to help the government seize control of the expropriated land and supervise its distribution, and later to set up cooperative farms. The land confiscated included 480,000 acres (190,000 ha) owned by United States corporations.[24] Months later, in retaliation, US President Dwight D. Eisenhower sharply reduced United States imports of Cuban sugar (Cuba's main cash crop), which led Guevara on 10 July 1960 to address over 100,000 workers in front of the Presidential Palace at a rally to denounce the "economic aggression" of the United States.[34] Time Magazine reporters who met with Guevara around this time described him as "guid(ing) Cuba with icy calculation, vast competence, high intelligence, and a perceptive sense of humor."[35]

—Urbano (a.k.a. Leonardo Tamayo),

fought with Guevara in Cuba and Bolivia[36]

Literacy

Along with land reform, Guevara stressed the need for national improvement in literacy. Before 1959 the official literacy rate for Cuba was between 60–76%, with educational access in rural areas and a lack of instructors the main determining factors.[37] As a result, the Cuban government at Guevara's behest dubbed 1961 the "year of education" and mobilized over 100,000 volunteers into "literacy brigades", who were then sent out into the countryside to construct schools, train new educators, and teach the predominantly illiterate guajiros (peasants) to read and write.[38][37] Unlike many of Guevara's later economic initiatives, this campaign was "a remarkable success". By the completion of the Cuban Literacy Campaign, 707,212 adults had been taught to read and write, raising the national literacy rate to 96%.[37]

Accompanying literacy, Guevara was also concerned with establishing universal access to higher education. To accomplish this the new regime introduced affirmative action to the universities. While announcing this new commitment, Guevara told the gathered faculty and students at the University of Las Villas that the days when education was "a privilege of the white middle class" had ended. "The University" he said, "must paint itself black, mulatto, worker, and peasant." If it did not, he warned, the people were going to break down its doors "and paint the University the colors they like."[39]

Notes

References

- Anderson, Jon Lee. Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, New York: 1997, Grove Press, pp. 372–425.

- "216 documented victims of Che Guevara in Cuba: 1957 to 1959" (PDF). ( 24.8 KiB),from Armando M. Lago, Ph.D.'sCuba: The Human Cost of Social Revolution.

- Skidmore 2008, pp. 273.

- Gómez Treto 1991, p. 115. "The Penal Law of the War of Independence (July 28, 1896) was reinforced by Rule 1 of the Penal Regulations of the Rebel Army, approved in the Sierra Maestra February 21, 1958, and published in the army's official bulletin (Ley penal de Cuba en armas, 1959)" (Gómez Treto 1991, p. 123).

- Gómez Treto 1991, pp. 115–116.

- Anderson 1997, pp. 372, 425.

- Anderson 1997, p. 376.

- Taibo 1999, p. 267.

- Kellner 1989, p. 52.

- Niess 2007, p. 60.

- Gómez Treto 1991, p. 116.

- Anderson 1997, p. 388.

- Rally For Castro: One Million Roar "Si" To Cuba Executions – Video Clip by Universal-International News, narrated by Ed Herlihy, from 22 January 1959

- Conflict, Order, and Peace in the Americas, by the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs, 1978, p. 121. "The US-supported Batista regime killed 20,000 Cubans"

- The World Guide 1997/98: A View from the South, by University of Texas, 1997, ISBN 1-869847-43-1, pg 209. "Batista engineered yet another coup, establishing a dictatorial regime, which was responsible for the death of 20,000 Cubans."

- Fidel: The Untold Story. (2001). Directed by Estela Bravo. First Run Features. (91 min). Viewable clip. "An estimated 20,000 people were murdered by government forces during the Batista dictatorship."

- Niess 2007, p. 61.

- Castañeda 1998, pp. 143–144.

- The Legacy of Che Guevara – a PBS online forum with author Jon Lee Anderson, November 20, 1997

- Different sources cite differing numbers of executions attributable to Guevara, with some of the discrepancy resulting from the question of which deaths to attribute directly to Guevara and which to the regime as a whole. Anderson (1997) gives the number specifically at La Cabaña prison as 55 (p. 387.), while also stating that "several hundred people were officially tried and executed across Cuba" as a whole (p. 387). (Castañeda 1998) notes that historians differ on the total number killed, with different studies placing it as anywhere from 200 to 700 nationwide (p. 143), although he notes that "after a certain date most of the executions occurred outside of Che's jurisdiction" (p. 143). These numbers are supported by the opposition-based Free Society Project / Cuba Archive, which gives the figure as 144 executions ordered by Guevara across Cuba in three years (1957–1959) and 105 "victims" specifically at La Cabaña, which according to them were all "carried out without due process of law". Of further note, much of the discrepancy in the estimates between 55 versus 105 executed at La Cabaña revolves around whether to include instances where Guevara had denied an appeal and signed off on a death warrant, but where the sentence was carried out while he traveled overseas from 4 June to 8 September, or after he relinquished his command of the fortress on 12 June 1959.

- Anderson 1997, p. 375.

- Kellner 1989, p. 54.

- Kellner 1989, p. 57.

- Kellner 1989, p. 58.

- Taibo 1999, pp. 282–285.

- Anderson 1997, p. 423.

- Ramadhian Fadillah (13 June 2012). "Soekarno soal cerutu Kuba, Che dan Castro" (in Indonesian). Merdeka.com. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- Anderson 1997, p. 431.

- Taibo 1999, p. 300.

- Che Guevara's Daughter Visits Bomb Memorial in Hiroshima by The Japan Times, 16 May 2008

- Anderson 1997, p. 435.

- Casey 2009, p. 25.

- Casey 2009, pp. 25–50.

- Kellner 1989, p. 55.

- "Castro's Brain", 1960.

- Latin America's New Look at Che by Daniel Schweimler, BBC News, October 9, 2007.

- Kellner 1989, p. 61.

- Latin lessons: What can we Learn from the World's most Ambitious Literacy Campaign? by The Independent, 7 November 2010

- Anderson 1997, p. 449

Gallery

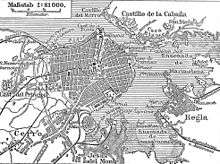

This 19th-century map of Havana shows La Cabaña's strategic location along the east side of the entrance to the city's harbor.

This 19th-century map of Havana shows La Cabaña's strategic location along the east side of the entrance to the city's harbor. Che Guevara's former office at La Cabaña.

Che Guevara's former office at La Cabaña. The inscription above the fortress gates.

The inscription above the fortress gates. An avenue between buildings of the fortress.

An avenue between buildings of the fortress.

External links

![]()