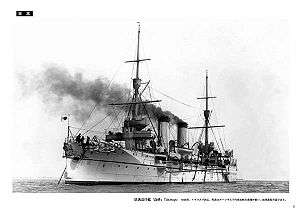

Japanese cruiser Takasago

Takasago (高砂, literally, High Sand, antiquated Japanese name for Formosa) was a protected cruiser of the Imperial Japanese Navy, designed and built by the Armstrong Whitworth shipyards in Elswick, in the United Kingdom. The name Takasago derives from a location in Hyōgo Prefecture, near Kobe.

Takasago | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Takasago |

| Ordered: | 1896 Fiscal Year |

| Builder: | Armstrong Whitworth, United Kingdom |

| Laid down: | April 1896 |

| Launched: | 18 May 1897 |

| Completed: | 17 May 1898 |

| Out of service: | 13 December 1904 |

| Fate: | Mined off Port Arthur |

| General characteristics | |

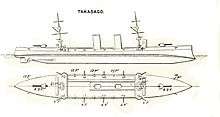

| Type: | Protected cruiser |

| Displacement: | 4,160 long tons (4,227 t) |

| Length: | 118.2 m (387 ft 10 in) w/l |

| Beam: | 14.78 m (48 ft 6 in) |

| Draft: | 5.18 m (17.0 ft) |

| Propulsion: | 2-shaft VTE; 12 boilers; 15,500 hp (11,600 kW); 1,000 tons coal |

| Speed: | 23.5 knots (27.0 mph; 43.5 km/h) |

| Complement: | 425 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

Background

Takasago was an improved design of the Argentine Navy cruiser Veinticinco de Mayo designed by Sir Philip Watts, who was also responsible for the design of the cruiser Izumi and the Naniwa-class cruisers. The Chilean Navy cruiser Chacabuco was the sister ship to Takasago; the Japanese cruiser Yoshino was sometimes also regarded as a sister ship to Takasago, due to the similarity in their design, armament and speed, although the two vessels were of different classes.

Takasago was laid down in April 1896, as Elswick hull number 660, as a private venture by Armstrong Whitworth, and was sold the Japan in July 1896. Launch occurred on 18 May 1897 and she was completed on 6 April 1898.[1]

Design

Takasago was a typical Elswick cruiser design, with a steel hull, divided into 109 waterproof compartments, a low forecastle, two smokestacks, and two masts. She made use of Harvey armor, which was intended to be able to protect against the impact of even an 8-inch armor-piercing shell. The prow was reinforced for ramming. The power plant was a triple expansion reciprocating steam engine with four cylindrical boilers, driving two screws.[2] In this aspect, the design was almost identical to that of Yoshino, however in terms of armament, Takasago was more heavily armed.

The main armament of Takasago were two separate 20.3 cm/45 Type 41 naval guns behind gun shields, which were placed on bow and stern. Secondary armament consisted of ten Elswick QF 6 inch /40 naval gun quick-firing guns mounted in casemates and in sponsons near the bridge. Takasago was also equipped with twelve QF 12-pounder 12 cwt naval guns, six QF 3-pounder Hotchkiss guns and five 457 mm (18 in) torpedo tubes.[2]

Service record

The first overseas deployment of Takasago was in 1900, to support Japanese naval landing forces which occupied the port city of Tianjin in northern China during the Boxer Rebellion, as part of the Japanese contribution to the Eight-Nation Alliance.

On 7 April 1902, Takasago and Asama were sent on a 24,718 nautical miles (45,778 km; 28,445 mi) voyage to the United Kingdom, as part of the official Japanese delegation to the coronation ceremonies of King Edward VII,[3] and in celebration of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance. After participating in a naval review held at Spithead on 16 August 1902 (originally scheduled from 24–27 June), Takasago and Asama visited numerous European and Asian ports (Singapore, Colombo, Suez, Malta, Lisbon on the way, Antwerp and Cork during their stay, and Gibraltar, Naples, Aden, Colombo, Singapore, Bangkok and Hong Kong on the way back). The ships returned safely to Japan on 28 November 1902.

Russo-Japanese War

With the start of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, Takasago participated in the bombardment of the Port Arthur naval base on the morning following the pre-emptive strike by Japanese destroyers against the Russian fleet in the opening stages of the naval Battle of Port Arthur, serving as flagship for Admiral Dewa Shigeto. The Japanese attack set fire to a portion of the town, and damaged a number of ships in the harbor, especially the cruisers Novik, Diana and Askold, and the battleship Petropavlovsk.[4] While participating in the subsequent blockade of the Russian fleet within the confines of the harbor, Takasago captured the Russian Far East Shipping Company merchant ship Manchuria, which was accepted into Japanese service as a prize of war and renamed Kantō Maru.

On 10 March 1904, Takasago participated in an attack on the Russian cruiser Bayan. On 15 May, she participated in the rescue of survivors from the battleships Yashima and Hatsuse, which had struck naval mines. Takasago was also in the Battle of the Yellow Sea on 10 August.

She returned to Japan for overhaul in October 1904. On returning to station on the night of 13 December 1904 after a reconnaissance mission during which it provided cover for a squadron of destroyers,[5] Takasago struck a naval mine 37 nautical miles (69 km; 43 mi) south of Port Arthur, which triggered a massive explosion in her ammunition magazine. The flooding could not be controlled, and her life boats could not be launched at night under blizzard conditions and heavy seas. Takasago sank in position 38°10′N 121°15′E, with the loss of 273 officers and crew. Some 162 survivors were rescued by the accompanying cruiser Otowa. Takasago was the last major Japanese warship lost in the Russo-Japanese War. Future Russian Admiral Aleksandr Kolchak, then a minesweeper captain at Port Arthur with the Russian Pacific Squadron, was credited with having placed the mine, and was awarded the prestigious Order of St Anna and Sword of St George for the action.[6]

Gallery

At Portsmouth

At Portsmouth At Portsmouth

At Portsmouth In Taiwan

In Taiwan In 1896

In 1896

Notes

- Brooke, Warships for Export

- Chesneau, Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1860–1905, page 229.

- http://www.walesonline.co.uk/videos-and-pics/photos/news-pictures/2008/11/27/tramcars-of-wales-91466-22353688/i14/

- Connaughton, Rising Sun and Tumbling Bear page 33

- Willmont, The Last Century of Sea Power page 98

- Kusnezov, Reeds in the Wind page 43

References

- Brooke, Peter (1999). Warships for Export: Armstrong Warships 1867-1927. Gravesend: World Ship Society. ISBN 0-905617-89-4.

- Chesneau, Roger (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1860–1905. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-133-5.

- Connaughton, Richard (2003). Rising Sun and Tumbling Bear. Cassell. ISBN 0-304-36657-9.

- Evans, David C.; Peattie, Mark R. (1997). Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887-1941. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-192-7.

- Howarth, Stephen (1983). The Fighting Ships of the Rising Sun: The Drama of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1895-1945. Atheneum. ISBN 0-689-11402-8.

- Jentsura, Hansgeorg (1976). Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869-1945. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-893-X.

- Roberts, John (ed). (1983). 'Warships of the world from 1860 to 1905 - Volume 2: United States, Japan and Russia. Bernard & Graefe Verlag, Koblenz. ISBN 3-7637-5403-2.

- Schencking, J. Charles (2005). Making Waves: Politics, Propaganda, And The Emergence Of The Imperial Japanese Navy, 1868-1922. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4977-9.

- Willmont, H.P. (2009). The Last Century of Sea Power: From Port Arthur to Chanak, 1894-1922. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-35214-2.

- Kusnezov, Nikita (2011). Reeds in the Wind. Createspace. ISBN 1-4565-5309-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Takasago (ship, 1898). |