Bark (botany)

Bark is the outermost layers of stems and roots of woody plants. Plants with bark include trees, woody vines, and shrubs. Bark refers to all the tissues outside the vascular cambium and is a nontechnical term.[1] It overlays the wood and consists of the inner bark and the outer bark. The inner bark, which in older stems is living tissue, includes the innermost layer of the periderm. The outer bark on older stems includes the dead tissue on the surface of the stems, along with parts of the outermost periderm and all the tissues on the outer side of the periderm. The outer bark on trees which lies external to the living periderm is also called the rhytidome.

Products derived from bark include: bark shingle siding and wall coverings, spices and other flavorings, tanbark for tannin, resin, latex, medicines, poisons, various hallucinogenic chemicals and cork. Bark has been used to make cloth, canoes, and ropes and used as a surface for paintings and map making.[2] A number of plants are also grown for their attractive or interesting bark colorations and surface textures or their bark is used as landscape mulch.[3][4]

Botanic description

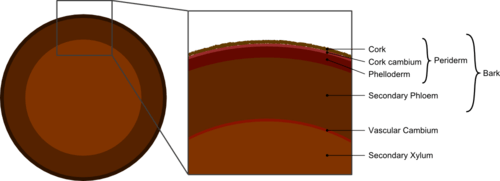

What is commonly called bark includes a number of different tissues. Cork is an external, secondary tissue that is impermeable to water and gases, and is also called the phellem. The cork is produced by the cork cambium which is a layer of meristematically active cells which serve as a lateral meristem for the periderm. The cork cambium, which is also called the phellogen, is normally only one cell layer thick and it divides periclinally to the outside producing cork. The phelloderm, which is not always present in all barks, is a layer of cells formed by and interior to the cork cambium. Together, the phellem (cork), phellogen (cork cambium) and phelloderm constitute the periderm.[5]

Cork cell walls contain suberin, a waxy substance which protects the stem against water loss, the invasion of insects into the stem, and prevents infections by bacteria and fungal spores.[6] The cambium tissues, i.e., the cork cambium and the vascular cambium, are the only parts of a woody stem where cell division occurs; undifferentiated cells in the vascular cambium divide rapidly to produce secondary xylem to the inside and secondary phloem to the outside. Phloem is a nutrient-conducting tissue composed of sieve tubes or sieve cells mixed with parenchyma and fibers. The cortex is the primary tissue of stems and roots. In stems the cortex is between the epidermis layer and the phloem, in roots the inner layer is not phloem but the pericycle.

From the outside to the inside of a mature woody stem, the layers include:[7]

- Bark

- Periderm

- Cork (phellem or suber), includes the rhytidome

- Cork cambium (phellogen)

- Phelloderm

- Cortex

- Phloem

- Periderm

- Vascular cambium

- Wood (xylem)

- Sapwood (alburnum)

- Heartwood (duramen)

- Pith (medulla)

In young stems, which lack what is commonly called bark, the tissues are, from the outside to the inside:

- Epidermis, which may be replaced by periderm

- Cortex

- Primary and secondary phloem

- Vascular cambium

- Secondary and primary xylem.

As the stem ages and grows, changes occur that transform the surface of the stem into the bark. The epidermis is a layer of cells that cover the plant body, including the stems, leaves, flowers and fruits, that protects the plant from the outside world. In old stems the epidermal layer, cortex, and primary phloem become separated from the inner tissues by thicker formations of cork. Due to the thickening cork layer these cells die because they do not receive water and nutrients. This dead layer is the rough corky bark that forms around tree trunks and other stems.

Periderm

Often a secondary covering called the periderm forms on small woody stems and many non-woody plants, which is composed of cork (phellem), the cork cambium (phellogen), and the phelloderm. The periderm forms from the phellogen which serves as a lateral meristem. The periderm replaces the epidermis, and acts as a protective covering like the epidermis. Mature phellem cells have suberin in their walls to protect the stem from desiccation and pathogen attack. Older phellem cells are dead, as is the case with woody stems. The skin on the potato tuber (which is an underground stem) constitutes the cork of the periderm.[8][9]

In woody plants the epidermis of newly grown stems is replaced by the periderm later in the year. As the stems grow a layer of cells form under the epidermis, called the cork cambium, these cells produce cork cells that turn into cork. A limited number of cell layers may form interior to the cork cambium, called the phelloderm. As the stem grows, the cork cambium produces new layers of cork which are impermeable to gases and water and the cells outside the periderm, namely the epidermis, cortex and older secondary phloem die.[10]

Within the periderm are lenticels, which form during the production of the first periderm layer. Since there are living cells within the cambium layers that need to exchange gases during metabolism, these lenticels, because they have numerous intercellular spaces, allow gaseous exchange with the outside atmosphere. As the bark develops, new lenticels are formed within the cracks of the cork layers.

Rhytidome

The rhytidome is the most familiar part of bark, being the outer layer that covers the trunks of trees. It is composed mostly of dead cells and is produced by the formation of multiple layers of suberized periderm, cortical and phloem tissue.[5] The rhytidome is especially well developed in older stems and roots of trees. In shrubs, older bark is quickly exfoliated and thick rhytidome accumulates.[11] It is generally thickest and most distinctive at the trunk or bole (the area from the ground to where the main branching starts) of the tree.

Chemical composition

Bark tissues make up by weight between 10–20% of woody vascular plants and consists of various biopolymers, tannins, lignin, suberin, suberan and polysaccharides.[12] Up to 40% of the bark tissue is made of lignin, which forms an important part of a plant, providing structural support by crosslinking between different polysaccharides, such as cellulose.[12]

Condensed tannin, which is in fairly high concentration in bark tissue, is thought to inhibit decomposition.[12] It could be due to this factor that the degradation of lignin is far less pronounced in bark tissue than it is in wood. It has been proposed that, in the cork layer (the phellogen), suberin acts as a barrier to microbial degradation and so protects the internal structure of the plant.[12][13]

Analysis of the lignin in bark wall during decay by the white-rot fungi Lentinula edodes (Shiitake mushroom) using 13C NMR revealed that the lignin polymers contained more Guaiacyl lignin units than Syringyl units compared to the interior of the plant.[12] Guaiacyl units are less susceptible to degradation as, compared to syringyl, they contain fewer aryl-aryl bonds, can form a condensed lignin structure and have a lower redox potential.[14] This could mean that the concentration and type of lignin units could provide additional resistance to fungal decay for plants protected by bark.[12]

Uses

Cork, sometimes confused with bark in colloquial speech, is the outermost layer of a woody stem, derived from the cork cambium. It serves as protection against damage from parasites, herbivorous animals and diseases, as well as dehydration and fire. Cork can contain antiseptics like tannins, that protect against fungal and bacterial attacks that would cause decay.

In some plants, the bark is substantially thicker, providing further protection and giving the bark a characteristically distinctive structure with deep ridges. In the cork oak (Quercus suber) the bark is thick enough to be harvested as a cork product without killing the tree;[15] in this species the bark may get very thick (e.g. more than 20 cm has been reported[16]). Some barks can be removed in long sheets; the smooth surfaced bark of birch trees has been used as a covering in the making of canoes, as the drainage layer in roofs, for shoes, backpacks etc. The most famous example of using birch bark for canoes is the birch canoes of North America.[17]

The inner bark (phloem) of some trees is edible; in Scandinavia, bark bread is made from rye to which the toasted and ground innermost layer of bark of scots pine or birch is added. The Sami people of far northern Europe used large sheets of Pinus sylvestris bark that were removed in the spring, prepared and stored for use as a staple food resource and the inner bark was eaten fresh, dried or roasted.[18]

Mechanical bark processing

Bark contains strong fibres known as bast, and there is a long tradition in northern Europe of using bark from coppiced young branches of the small-leaved lime (Tilia cordata) to produce cordage and rope, used for example in the rigging of Viking Age longships.[19]

Among the commercial products made from bark are cork, cinnamon, quinine[20] (from the bark of Cinchona)[21] and aspirin (from the bark of willow trees). The bark of some trees notably oak (Quercus robur) is a source of tannic acid, which is used in tanning. Bark chips generated as a by-product of lumber production are often used in bark mulch in western North America. Bark is important to the horticultural industry since in shredded form it is used for plants that do not thrive in ordinary soil, such as epiphytes.

Bark chip extraction

Wood bark contains lignin; when it is pyrolyzed (subjected to high temperatures in the absence of oxygen), it yields a liquid bio-oil product rich in natural phenol derivatives. The phenol derivatives are isolated and recovered for application as a replacement for fossil-based phenols in phenol-formaldehyde (PF) resins used in Oriented Strand Board (OSB) and plywood.[22]

Bark removal

Cut logs are inflamed either just before cutting or before curing. Such logs and even trunks and branches found in their natural state of decay in forests, where the bark has fallen off, are said to be decorticated.

A number of living organisms live in or on bark, including insects,[23] fungi and other plants like mosses, algae and other vascular plants. Many of these organisms are pathogens or parasites but some also have symbiotic relationships.

Bark repair

The degree to which trees are able to repair gross physical damage to their bark is very variable. Some are able to produce a callus growth which heals over the wound rapidly, but leaves a clear scar, whilst others such as oaks do not produce an extensive callus repair. Frost crack and sun scald are examples of damage found on tree bark which trees can repair to a degree, depending on the severity.

The patterns left in the bark of a Chinese Evergreen Elm after repeated visits by a Yellow-Bellied Sapsucker (woodpecker) in early 2012.

The patterns left in the bark of a Chinese Evergreen Elm after repeated visits by a Yellow-Bellied Sapsucker (woodpecker) in early 2012. The self-repair of the Chinese Evergreen Elm showing new bark growth, lenticels, and other self-repair of the holes made by a Yellow-Bellied Sapsucker (woodpecker) about two years earlier.

The self-repair of the Chinese Evergreen Elm showing new bark growth, lenticels, and other self-repair of the holes made by a Yellow-Bellied Sapsucker (woodpecker) about two years earlier.- Alder bark (Alnus glutinosa) with characteristic lenticels and abnormal lenticels on callused areas.

- Sun scald damage on Sitka spruce

Gallery

Eucalypt bark

Eucalypt bark- Close-up of living bark on a tree in England

.jpg) Acer capillipes (Red Snakebark Maple)

Acer capillipes (Red Snakebark Maple) Monterey Pine bark

Monterey Pine bark- A rare Black Poplar tree, showing the bark and burls.

- The typical appearance of Sycamore bark from an old tree.

- Quercus robur bark with a large burl and lichen.

Kauri bark

Kauri bark Beech bark with callus growth following fire (heat) damage

Beech bark with callus growth following fire (heat) damage Damaged bark

Damaged bark "Rainbow" Eucalyptus bark on the Hawaiian island of Maui

"Rainbow" Eucalyptus bark on the Hawaiian island of Maui

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bark. |

- Bark beetle

- Bark painting

- Trunk (botany)

- Bark isolate

- Bark-binding, a diseased condition of tree bark

References

- Raven, Peter H.; Evert, Ray F.; Curtis, Helena (1981), Biology of Plants, New York, N.Y.: Worth Publishers, p. 641, ISBN 0-87901-132-7, OCLC 222047616

- Taylor, Luke. 1996. Seeing the Inside: Bark Painting in Western Arnhem Land. Oxford Studies in Social and Cultural Anthropology. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Sandved, Kjell Bloch, Ghillean T. Prance, and Anne E. Prance. 1993. Bark: the Formation, Characteristics, and Uses of Bark around the World. Portland, Or: Timber Press.

- Vaucher, Hugues, and James E. Eckenwalder. 2003. Tree Bark: a Color Guide. Portland: Timber

- Dickison, WC. 2000. Integrative Plant Anatomy, Academic Press, San Diego, 186–195.

- "Botany Glossary "P"". .puc.edu. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- Pereira, Helena (2007), Cork, Amsterdam: Elsevier, p. 8, ISBN 0-444-52967-5, OCLC 162131397

- Artschwager, E (1924). "Studies on the potato tuber". J. Agr. Res. 27: 809–835.

- Peterson, R.L.; Barker, W.G. (1979). "Early tuber development from explanted stolon nodes of Solanum tuberosum var. Kennebec". Bot. Gaz. 140: 398–406. doi:10.1086/337104.

- Mauseth, James D. (2003), Botany: an Introduction to Plant Biology, p. 229, ISBN 0-7637-2134-4

- Katherine Easu (1977). Anatomy of Seed Plants. Plant Anatomy (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 185. ISBN 0-471-24520-8.

- Vane, C. H.; et al. (2006). "Bark decay by the white-rot fungus Lentinula edodes: Polysaccharide loss, lignin resistance and the unmasking of suberin". International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation. 57 (1): 14–23. doi:10.1016/j.ibiod.2005.10.004.

- Kolattukudy, P.E. (1984). "Biochemistry and function of cutin and suberin". Canadian Journal of Botany. 62: 2918–2933. doi:10.1139/b84-391.

- Vane, C. H.; et al. (2001). "Degradation of Lignin in Wheat Straw during Growth of the Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) Using Off-line Thermochemolysis with Tetramethylammonium Hydroxide and Solid-State 13C NMR". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 49 (6): 2709–2716. doi:10.1021/jf001409a.

- Aronson J.; Pereira J.S.; Pausas J.G., eds. (2009). "Cork Oak Woodlands on the Edge: conservation, adaptive management, and restoration". Washington DC: Island Press.

- Paulo Fernandes (3 January 2011). "j.g. pausas' blog " Bark thickness: a world record?". Jgpausas.blogs.uv.es. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2010.07.010. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- Adney, Tappan, and Howard Irving Chapelle. 1964. The Bark Canoes and Skin Boats of North America. Washington: Smithsonian Institution.

- Zackrisson, O.; Östlund, L.; Korhonen, O.; Bergman, I. (200), "The ancient use of Pinus sylvestris L. (scots pine) inner bark by Sami people in northern Sweden, related to cultural and ecological factors = Ancienne usage d\'écorce de Pinus sylvestris L. (Pin écossais) par les peuples Sami du nord de la Suède en relation avec les facteurs écologiques et culturels", Vegetation History and Archaeobotany, 9 (2): 99–109, doi:10.1007/bf01300060

- Myking, T.; Hertzberg, A.; Skrøppa, T. (2005). "History, manufacture and properties of lime bast cordage in northern Europe". Forestry. 78 (1): 65–71. doi:10.1093/forestry/cpi006.

- Duran-Reynals, Marie Louise de Ayala. 1946. The Fever Bark Tree; the Pageant of Quinine. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday.

- Markham, Clements R. 1880. Peruvian Bark. A Popular Account of the Introduction of Chinchona Cultivation into British India. London: J. Murray.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 April 2008. Retrieved 30 January 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Lieutier, François. 2004. Bark and Wood Boring Insects in Living Trees in Europe, a Synthesis. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Other references

- Cédric Pollet, Bark: An Intimate Look at the World's Trees. London, Frances Lincoln, 2010. (Translated by Susan Berry) ISBN 978-0-7112-3137-5