French colonization of Texas

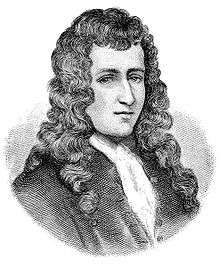

The French colonization of Texas began with the establishment of a fort in present-day southeastern Texas. It was established in 1685 near Arenosa Creek and Matagorda Bay by explorer Robert Cavelier de La Salle. He intended to found the colony at the mouth of the Mississippi River, but inaccurate maps and navigational errors caused his ships to anchor instead 400 miles (640 km) to the west, off the coast of Texas. The colony survived until 1688. The present-day town of Inez is near the fort's site. The colony faced numerous difficulties during its brief existence, including Native American raids, epidemics, and harsh conditions. From that base, La Salle led several expeditions to find the Mississippi River. These did not succeed, but La Salle did explore much of the Rio Grande and parts of east Texas.

During one of his absences in 1686, the colony's last ship was wrecked, leaving the colonists unable to obtain resources from the French colonies of the Caribbean. As conditions deteriorated, La Salle realized the colony could survive only with help from the French settlements in Illinois Country to the north, along the Mississippi and Illinois Rivers. His last expedition ended along the Brazos River in early 1687, when La Salle and five of his men were murdered during a mutiny. Although a handful of men reached Illinois Country, help never made it to the fort. Most of the remaining members of the colony were killed during a Karankawa raid in late 1688, four children survived after being adopted as captives. Although the colony lasted only three years, it established France's claim to possession of the region that is now Texas. The United States later claimed, unsuccessfully, this region as part of the Louisiana Purchase because of the early French colony.

Spain learned of La Salle's mission in 1686. Concerned that the French colony could threaten Spain's control over the Viceroyalty of New Spain and the unsettled southeastern region of North America, the Crown funded multiple expeditions to locate and eliminate the settlement. The unsuccessful expeditions helped Spain to better understand the geography of the Gulf Coast region. When the Spanish finally discovered the remains of the French colony at the fort in 1689, they buried the cannons and burned the buildings. Years later, Spanish authorities built a presidio at the same location. When the presidio was abandoned, the site of the French settlement was lost to history. The fort was rediscovered by historians and excavated in 1996, and the area is now an archaeological site. In 1995, researchers located the ship La Belle in Matagorda Bay, with several sections of the hull remaining virtually intact. They constructed a cofferdam, the first to be used in North America to excavate the ship as if in dry conditions. In 2000, excavations revealed three of the original structures of the fort, as well as three graves of Frenchmen.

La Salle expeditions

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Texas | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

First expedition

By the late 17th century, much of North America had been claimed by European countries. Spain had claimed Florida as well as modern-day Mexico and much of the southwestern part of the continent. The northern and central Atlantic coast had become the Thirteen Colonies, and New France comprised much of what is now eastern Canada as well as the central Illinois Country. The French feared that their colonies were vulnerable to a potential attack from its neighboring colonies. In 1681, French nobleman Robert Cavelier de La Salle launched an expedition down the Mississippi River from New France, at first believing he would find a path to the Pacific Ocean.[1] Instead, La Salle found a route to the Gulf of Mexico. Although Hernando De Soto had explored and claimed this area for Spain 140 years before,[2] on April 9, 1682, La Salle claimed the Mississippi River valley for French king Louis XIV, naming the territory Louisiana in his honor.[3]

Unless France established a base at the mouth of the Mississippi, Spain would have an opportunity to control the entire Gulf of Mexico and potentially pose a threat to New France's southern borders.[4] La Salle believed that the Mississippi River was near the eastern edge of New Spain. On his return to France in 1684, he proposed to the Crown the establishment of a colony at the mouth of the river. The colony could provide a base for promoting Christianity among the native peoples as well as a convenient location for attacking the Spanish province of Nueva Vizcaya and gaining control of its lucrative silver mines.[2][5] He argued that a small number of Frenchmen could successfully invade New Spain by allying themselves with some of the more than 15,000 Native Americans who were angry over Spanish enslavement.[2] After Spain declared war on France in October 1667, King Louis agreed to support La Salle's plan.[2] He was to return to North America and confirm "the Indians' allegiance to the crown, leading them to the true faith, and maintaining intertribal peace".[5]

Second expedition

La Salle originally planned to sail to New France, journey overland to the south and Illinois Country, and then travel down the Mississippi River to its mouth.[6] To spite Spain, Louis XIV insisted that La Salle sail through the Gulf of Mexico, which Spain considered its exclusive property.[7] Although La Salle had requested only one ship, on July 24, 1684, he left La Rochelle, France with four: the 36-gun man of war Le Joly, the 300-ton storeship L'Aimable, the barque La Belle, and the ketch St. François.[8][9][10] Although Louis XIV had provided both Le Joly and La Belle, La Salle desired more cargo space and leased L'Aimable and St. François from French merchants. Louis also provided 100 soldiers and full crews for the ships, as well as funds to hire skilled workers to join the expedition. La Salle was forced to purchase trade goods himself for expected encounters with Native Americans. .[11]

The ships carried a total of nearly 300 people, including soldiers, artisans and craftsmen, six Catholic missionaries, eight merchants, and over a dozen women and children.[8][12] Shortly after their departure, France and Spain ceased hostilities, and Louis was no longer interested in sending La Salle further assistance.[10] Details of the voyage were kept secret so that Spain would not learn about it. La Salle's naval commander, the Sieur de Beaujeu, resented La Salle's keeping their destination until the party was well underway. The discord between the two intensified when they reached Saint-Domingue, on the island of Hispaniola, and quarreled over where to anchor. Beaujeu sailed to another part of the island, allowing Spanish privateers to capture the St. François, which had been fully loaded with supplies, provisions, and tools for the colony.[13]

During the 58-day voyage, two people died of illness and one woman gave birth to a child.[12] The voyage to Saint-Domingue had lasted longer than expected, and provisions ran low, especially after the loss of the St. François. La Salle had little money with which to replenish supplies, and finally two of the merchants aboard the expedition sold some of their trade goods to the islanders, and lent their profits to La Salle. To fill the gaps left after several men deserted, La Salle recruited a few islanders to join the expedition.[14]

In late November 1684, when La Salle had fully recovered from a severe illness, the three remaining ships continued their search for the Mississippi River delta.[13] Before they left Santo Domingo, local sailors warned that strong Gulf currents flowed east and would tug the ships toward the Florida straits unless they corrected for it.[15] On December 18, the ships reached the Gulf of Mexico and entered waters that Spain claimed as its territory.[16] None of the members of the expedition had ever been in the Gulf of Mexico or knew how to navigate it.[17] Due to a combination of inaccurate maps, La Salle's previous miscalculation of the latitude of the mouth of the Mississippi River, and overcorrection for the currents, the expedition failed to find the Mississippi.[15] Instead, they landed at Matagorda Bay in early 1685, 400 miles (640 km) west of the Mississippi.[15]

First settlement

On February 20, the colonists set foot on land for the first time in three months since leaving Saint-Domingue. They set up a temporary camp near the site of the present-day Matagorda Island Lighthouse.[18] The chronicler of the expedition, Henri Joutel, described his first view of Texas: "The country did not seem very favorable to me. It was flat and sandy but did nevertheless produce grass. There were several salt pools. We hardly saw any wild fowl except some cranes and Canadian (sic) geese which were not expecting us."[19]

Against Beaujeu's advice, La Salle ordered La Belle and the Aimable "to negotiate the narrow and shallow pass" to bring the supplies closer to the campsite.[20] To lighten L'Aimable's load, its eight cannons and a small portion of its cargo were removed. After La Belle successfully negotiated the pass, La Salle sent her pilot to L'Aimable to assist with the navigation, but L'Aimable's captain refused the help.[19] As the Aimable set sail, a band of Karankawa approached and carried off some of the settlers. La Salle led a small group of soldiers to rescue them, leaving no one to direct the Aimable. When he returned, he found the Aimable grounded on a sandbar.[18] Upon hearing that the captain had ordered the ship to sail forward after it had struck a sandbar, La Salle became convinced that the captain had deliberately grounded the ship.[21]

For several days the men attempted to salvage the tools and provisions that had been loaded on the Aimable, but a bad storm prevented them from recovering more than food, cannons, powder, and a small amount of the merchandise. The ship sank on March 7.[20] The French watched the Karankawa loot the wreckage. As French soldiers approached the Native American village to retrieve their supplies, the villagers hid. On discovering the deserted village, the soldiers not only reclaimed the looted merchandise but also took animal pelts and two canoes. The angry Karankawa attacked, killing two Frenchmen and injuring others.[20]

Beaujeu, having fulfilled his mission in escorting the colonists across the ocean, returned to France aboard the Joly in mid-March 1685.[22] Many of the colonists chose to return to France with him,[23] leaving approximately 180.[24] Although Beaujeu delivered a message from La Salle requesting additional supplies, French authorities, having made peace with Spain, never responded.[10][25] The remaining colonists suffered from dysentery and venereal diseases, and people died daily.[22] Those who were fit helped build crude dwellings and a temporary fort on Matagorda Island.[24]

Fort

On March 24, La Salle took 52 men in five canoes to find a less exposed settlement site. They found Garcitas Creek that had fresh water and fish, with good soil along its banks. They named it Rivière aux Boeufs for the nearby buffalo herds. The fort was constructed on a bluff overlooking the creek, 1.5 leagues from its mouth. Two men died, one of a rattlesnake bite and another from drowning while trying to fish.[24] At night, the Karankawa would sometimes surround the camp and howl, but the soldiers could scare them away with a few gun shots.[26] The fort has sometimes been referred to as "Fort St. Louis" but that name was not used during the life of the settlement and appears to be a later invention.[27]

In early June, La Salle summoned the rest of the colonists from the temporary campsite to the new settlement site. Seventy people began the 50-mile (80 km) overland trek on June 12. All of the supplies had to be hauled from the Belle, a physically draining task that was finally completed by the middle of July. The last load was accompanied by the 30 men who had remained behind to guard the ship.[26] Although trees grew near the site, they were not suitable for building, and timber had to be transported to the building site from several miles inland. Some timbers were salvaged from the Aimable.[25] By the end of July, over half of the settlers had died, most from a combination of scant rations and overwork.[26]

The remaining settlers built a large two-story structure at the center of the settlement. The ground floor was divided into three rooms: one for La Salle, one for the priests, and one for the officers of the expedition.[25] The upper story consisted of a single room used to store supplies. Surrounding the fort were several smaller structures to provide shelter for the other members of the expedition. The eight cannons, each weighing 700 to 1,200 pounds (320 to 540 kg), had been salvaged from L'Aimable and were positioned around the colony for protection.[28]

Difficulties

For several months after the permanent camp was built, the colonists took short trips to explore their surroundings. At the end of October 1685, La Salle decided to undertake a longer expedition and reloaded the Belle with many of the remaining supplies. He took 50 men, plus the Belle's crew of 27 sailors, leaving behind 34 men, women, and children. Most of the men traveled with La Salle in canoes, while the Belle followed further off the coast. After three days of travel, they learned of hostile Native Americans in the area. Twenty of the Frenchmen attacked the Native American village, where they found Spanish artifacts.[29] Several of the men died on this expedition from eating prickly pear. The Karankawa killed a small group of the men who had camped on shore, including the captain of the Belle.[30]

From January until March 1686, La Salle and most of his men searched overland for the Mississippi River, traveling towards the Rio Grande, possibly as far west as modern-day Langtry, Texas.[30][31] The men questioned the local Native American tribes, asking for information on the locations of the Spaniards and the Spanish mines, offering gifts, and telling stories that portrayed the Spanish as cruel and the French as benevolent.[10] When the group returned, they were unable to find the Belle where they had left her and were forced to walk back to the fort.[30][31]

The following month they traveled east, hoping to locate the Mississippi and return to Canada.[31] During their travels, the group encountered the Caddo, who gave the Frenchmen a map depicting their territory, that of their neighbors, and the location of the Mississippi River.[32] The Caddo often made friendship pacts with neighboring peoples and extended their policy of peaceful negotiation to the French.[33] While visiting the Caddo, the French met Jumano traders, who reported on the activities of the Spanish in New Mexico. These traders later informed Spanish officials of the Frenchmen they had seen.[34]

Four of the men deserted when they reached the Neches River. La Salle and one of his nephews became very ill, forcing the group to halt for two months. While the men recovered, the group ran low on food and gunpowder.[32] In August, the eight surviving members of the expedition[32] returned to Fort Saint Louis, having never left East Texas.[35]

While La Salle was gone, six of those who had remained on the Belle finally arrived at Fort Saint Louis. According to them, the new captain of the Belle was always drunk. Many of the sailors did not know how to sail, and they grounded the boat on Matagorda Peninsula. The survivors took a canoe to the fort, leaving the ship behind.[36] The destruction of their last ship left the settlers stranded on the Texas coast, with no hope of gaining assistance from the French colonies in the Caribbean Sea.[22]

By early January 1687, fewer than 45 of the original 180 people remained in the colony, which was beset by internal strife.[35][37] La Salle believed that their only hope of survival lay in trekking overland to request assistance from New France,[36] and some time that month he led a final expedition to try to reach the Illinois Country.[35] Fewer than 20 people remained at Fort Saint Louis, primarily women, children, and those deemed unfit, as well as seven soldiers and three missionaries with whom La Salle was unhappy.[37] Seventeen men were included on the expedition, including La Salle, his brother, and two of his nephews. While camping near present-day Navasota on March 18, several of the men quarreled over the division of buffalo meat. That night, an expedition member killed one of La Salle's nephews and two other men in their sleep. The following day La Salle was killed while approaching the camp to investigate his nephew's disappearance.[35] Infighting led to the deaths of two other expedition members within a short time.[38] Two of the surviving members, including Jean L'Archeveque, joined the Caddo. The remaining six men, led by Henri Joutel, made their way to Illinois Country. During their journey through Illinois to Canada, the men did not tell anyone that La Salle was dead. They reached France in the summer of 1688 and informed King Louis of La Salle's death and the horrible conditions in the colony. Louis did not send aid.[39]

Spanish response

Spanish pirate and guarda costa privateer Juan Corso had independently heard rumors of the colony as early as the Spring of 1685; he set out to eliminate the settlement but his ship was caught in rough seas and poor weather and was lost with all hands.[40] Afterwards La Salle's mission had remained nearly secret until 1686 when former expedition member Denis Thomas, who had deserted in Santo Domingo, was arrested for piracy. Trying to have his punishment reduced, Thomas informed his Spanish jailers of La Salle's plan to found a colony and eventually conquer Spanish silver mines. Despite his confession, Thomas was hanged.[41]

The Spanish government felt the French colony would be a threat to their mines and shipping routes, and Carlos II's Council of War thought that "Spain needed swift action 'to remove this thorn which has been thrust into the heart of America. The greater the delay the greater the difficulty of attainment.'"[10] The Spanish had no idea where to find La Salle, and in 1686 they sent a sea expedition and two land expeditions to try to locate his colony. Although the expeditions were unable to find La Salle, they did narrow the search to the area between the Rio Grande and the Mississippi.[42] Four Spanish expeditions the following year failed to find La Salle, but helped Spain to better understand the geography of the Gulf Coast region.[42]

In 1688, the Spanish sent three more expeditions, two by sea and one by land. The land expedition, led by Alonso De León, discovered Jean Gery, who had deserted the French colony and was living in Southern Texas with the Coahuiltecans.[43] Using Gery as a translator and guide, De León finally found the French fort in late April 1689.[44] The fort and the five crude houses surrounding it were in ruins.[31] Several months before, the Karankawa had attacked the settlement. They destroyed the structures and left the bodies of three people, including a woman who had been shot in the back.[44] A Spanish priest who had accompanied De León conducted funeral services for the three victims.[31] The chronicler of the Spanish expedition, Juan Bautista Chapa, wrote that the devastation was God's punishment for opposing the Pope, as Pope Alexander VI had granted the Indies exclusively to the Spanish.[44][45] The remains of the fort were destroyed by the Spanish, who also buried the French cannons left behind.[46] The Spanish later built a fort on the same location.[47]

In early 1689, Spanish authorities received a plea, written in French. Jumano scouts had received these papers from the Caddo, who asked that they be delivered to the Spanish. The papers included a parchment painting of a ship, as well as a written message from Jean L'Archevêque. The message read:

I do not know what sort of people you are. We are French[;] we are among the savages[;] we would like much to be Among the Christians such as we are[.] ... we are solely grieved to be among beasts like these who believe neither in God nor in anything. Gentlemen, if you are willing to take us away, you have only to send a message. ... We will deliver ourselves up to you.[45]

De León later rescued L'Archeveque and his companion Jacques Grollet. On interrogation, the men maintained that over 100 of the French settlers had died of smallpox, and the others had been killed by Native Americans.[45] The only people known to have survived the final attack were the Talon children, who had been adopted by the Karankawa.[48] According to the children, the settlement had been attacked around Christmas of 1688, and all the remaining settlers had been killed.[45]

Legacy

Only 15 or 16 people survived the colony. Six returned to France, while nine others were captured by the Spanish, including the four children who had been spared by the Karankawa.[35] The children were initially brought to the viceroy of New Spain, the Conde de Galve, who treated them as servants. Two of the boys, Pierre and Jean-Baptiste, later returned to France.[48] Of the remaining Spanish captives, three became Spanish citizens and settled in New Mexico.[35] Although the French colony had been utterly destroyed, Spain feared that another French attempt was inevitable. For the first time, the Spanish crown authorized small outposts in eastern Texas and at Pensacola.[46] In 1722, the Spanish built a fort, Presidio La Bahia, and Mission Nuestra Señora del Espíritu Santo de Zúñiga on the site of Fort Saint Louis.[49]

_1836.jpg)

France did not abandon its claims to Texas until November 3, 1762, when it ceded all of its territory west of the Mississippi River to Spain in the Treaty of Fontainebleau, following its defeat by Great Britain in the Seven Years' War. It ceded New France to Britain.[50] In 1803, three years after Spain had returned Louisiana to France, Napoleon sold the territory to the United States. The original agreement between Spain and France had not explicitly specified the borders of Louisiana, and the descriptions in the documents were ambiguous and contradictory.[51] The United States insisted that its purchase included all of the territory France had claimed, including all of Texas.[51] The dispute was not resolved until the Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819, in which Spain ceded Florida to the United States in return for the United States' relinquishing its claim on Texas.

The official boundary of Texas was set at the Sabine River (the current boundary between Texas and Louisiana), and following the Red and Arkansas rivers to the 42nd parallel (California's current northern border).[52]

Excavation

In 1908, historian Herbert Eugene Bolton identified an area along Garcitas Creek, near Matagorda Bay, as the location of Fort St. Louis. Other historians, before and after Bolton, argued that the fort was located on Lavaca River in Jackson County.[53] Five decades later, the University of Texas at Austin funded a partial excavation of Bolton's site, a part of the Keeran ranch.[53][54] Although several thousand items were recovered, archaeologists could not accurately distinguish between French and Spanish artifacts of the 17th century, and no report on the findings was ever issued. In the 1970s, the artifacts were reexamined by Kathleen Gilmore, an archaeologist at Southern Methodist University. She determined that while most of the artifacts were Spanish, some definitively matched artifacts recovered from French and French-Canadian excavations of the same time period.[54]

In late 1996, Keeran ranch workers exploring with metal detectors located eight cast-iron cannons buried near Garcitas Creek. After excavating the cannons, the Texas Historical Commission (THC) confirmed they were from Fort Saint Louis.[53] In 2000 a THC excavation discovered the locations of three of the buildings that had housed the French colony[55][56] and the three graves dug by the Spanish.[57][58]

For decades, the THC had also been searching for the wreckage of La Belle. In 1995, the shipwreck was discovered in Matagorda Bay. Researchers excavated a 792-pound (359 kg) cast-bronze cannon from the waters, as well as musket balls, bronze straight pins, and trade beads.[59] Large sections of the wooden hull were intact, protected from the damaging effects of warm salt water by layers of muddy sediment which "essentially creat[ed] an oxygen-free time capsule".[60][61] La Belle was the oldest French shipwreck discovered in the Western Hemisphere to that date. To enable the archaeologists to recover as many of the artifacts as possible, a cofferdam was constructed around the ship. The cofferdam held back the waters of the bay, allowing archaeologists to conduct the excavation as if it were on land. This was the first attempt in North America to excavate a shipwreck in dry conditions. Previous shipwreck excavations using cofferdams were completed in Europe, but never on a ship as large as the Belle.[62]

The National Underwater and Marine Agency searched for L'Aimable from 1997 until 1999. Although they found a promising location, the ship was buried under more than 25 feet (7.6 m) of sand and could not be reached.[63]

See also

- France–Republic of Texas relations, 1839–1845

References

- Bannon, John Francis (1997), The Spanish Borderlands Frontier, 1513–1821, Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, p. 94, ISBN 978-0-8263-0309-7

- Weber, David J. (1992), The Spanish Frontier in North America, Yale Western Americana Series, New Haven Connecticut: Yale University Press, p. 148, ISBN 978-0-300-05198-8

- Chipman, Donald E. (2010) [1992], Spanish Texas, 1519–1821 (revised ed.), Austin: University of Texas Press, p. 72, ISBN 978-0-292-77659-3

- Chipman (2010), p. 73

- Calloway, Colin G. (2003), One Vast Winter Count: The Native American West Before Lewis and Clark, History of the American West, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, p. 250, ISBN 978-0-8032-1530-6

- Bruseth, James E.; Turner, Toni S. (2005), From a Watery Grave: The Discovery and Excavation of La Salle's Shipwreck, La Belle, College Station: Texas A&M University Press, p. 76, ISBN 978-1-58544-431-1

- Bruseth & Turner (2005), p. 19

-

- Weddle, Robert S. (1991), The French Thorn: Rival Explorers in the Spanish Sea, 1682–1762, College Station: Texas A&M University Press, p. 13, ISBN 978-0-89096-480-4

- Chipman (2010), p. 74

- Weber (1992), p. 149

- Bruseth & Turner (2005), p. 20

- Weddle (1991), p. 16

- Chipman (2010), p. 75

- Weddle (1991), p. 17

- Chipman (2010), p. 76

- Weddle (1991), p. 19

- Weddle (1991), p. 20

- Weddle (1991), p. 23

- Bruseth & Turner (2005), p. 23

- Weddle (1991), p. 24

- Bruseth & Turner (2005), p. 26

- Chipman (2010), p. 77

- Weddle (1991), p. 25

- Weddle (1991), p. 27

- Bruseth & Turner (2005), p. 27

- Weddle (1991), p. 28

- Weddle, Robert (2010-06-15). "La Salle's Texas Settlement". Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 2017-11-09.

- Bruseth & Turner (2005), p. 28

- Weddle (1991), p. 29

- Weddle (1991), p. 30

- Chipman (2010), p. 83

- Weddle (1991), p. 34

- Calloway (2003), p. 252

- Calloway (2003), p. 253

- Chipman (2010), p. 84

- Weddle (1991), p. 31

- Weddle (1991), p. 35

- Weddle (1991), p. 38

- Bannon (1997), p. 97

- Marley, David (2010). Pirates of the Americas. Santa Barbara CA: ABC-CLIO. pp. 85–88. ISBN 9781598842012. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- Bruseth & Turner (2005), pp. 7-8

- Weber (1992), p. 151

- Weber (1992), pp. 151-152

- Weber (1992), p. 152

- Calloway (2003), p. 255

- Weber (1992), p. 153

- Weber (1992), p. 168

- Calloway (2003), p. 256

- Roell, Craig H.; Weddle, Robert S. (September 19, 2010). "Nuestra Señora de Loreto de la Bahia Presidio". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved April 7, 2011.

- Weber (1992), p. 198

- Weber (1992), p. 291

- Weber (1992), p. 299

- Turner, Allan (February 16, 1997), "Cannons' discovery ends debate on LaSalle fort", Houston Chronicle, Houston, TX, p. City and State, 2, retrieved 2007-11-07

- Bruseth & Turner (2005), p. 32

- Mosely, Laurie. "Information About Archeology: Fort Saint Louis". Texas Archeological Society. Archived from the original on 2007-12-24. Retrieved 2007-11-06.

- Kever, Jeannie (September 17, 2000), "The first French Colony in Texas", Houston Chronicle, retrieved 2007-11-07

- Fort St. Louis Excavation Highlights, Texas Historical Commission, archived from the original on 2007-08-30, retrieved 2007-11-04

- Kever, Jeannie (December 3, 2000), "Hot on their tracks: Remains of Settlers at site of La Salle Fort thrill archaeologists", Houston Chronicle, retrieved 2007-11-07

- Keith, Donald H.; Carlin, Worth; de Bry, John (1997), "A bronze cannon from La Belle, 1686: its construction, conservation, and display", The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 26 (2): 144–158, doi:10.1111/j.1095-9270.1997.tb01326.x

- Turner, Allan (July 14, 1995), "History surfaces in Matagorda Bay", Houston Chronicle, retrieved 2007-11-07

- Turner, Allan (July 30, 1995), "History rising from the bay's murky depths: La Salle ship one of many Matagorda victims", Houston Chronicle, p. State section, page 1, retrieved 2007-11-07

- Bruseth & Turner (2005), p. 48

- Bruseth & Turner (2005), p. 45

Further reading

- Lagarde, François, ed. (2003), The French in Texas: History, Migration, Culture, Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, ISBN 978-0-292-70528-9