Annapolis Royal

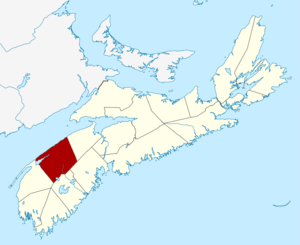

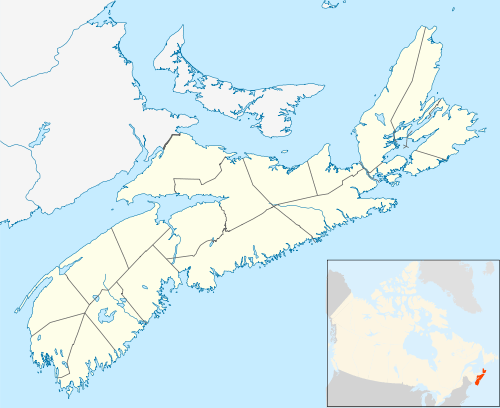

Annapolis Royal, formerly known as Port Royal,[2][3] is a town located in the western part of Annapolis County, Nova Scotia, Canada.

Annapolis Royal | |

|---|---|

Seaward view at Annapolis Royal | |

Flag | |

Annapolis Royal Location of Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia | |

| Coordinates: 44°44′30″N 65°30′55″W | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| Municipality | Annapolis County |

| Founded | 1605 (as Port Royal) |

| Incorporated | November 29, 1892 |

| Electoral Districts Federal | West Nova |

| Provincial | Annapolis |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Bill MacDonald |

| • Governing Body | Annapolis Royal Town Council |

| • MLA | Stephen McNeil (L) |

| • MP | Chris d’Entremont [C |

| Area (2016)[1] | |

| • Total | 2.04 km2 (0.79 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 7 m (23 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (2016)[1] | |

| • Total | 491 |

| • Density | 240.8/km2 (624/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Annapolitan |

| Time zone | UTC-4 (AST) |

| Postal code | B0S1A0 |

| Area code(s) | 902 |

| Telephone Exchange | 526, 532 |

| Median Earnings* | $40,949 |

| NTS Map | 021A12 |

| GNBC Code | CAASF |

| Website | |

| |

| Official name | Annapolis Royal Historic District National Historic Site of Canada |

| Designated | 1994 |

Today's Annapolis Royal is the second French settlement known by the same name and should not be confused with the 1605 French settlement of Port-Royal National Historic Site also known as the Habitation. This new French settlement was renamed in honour of Queen Anne following the Siege of Port Royal in 1710 by Britain.[4] The town was the capital of Acadia and later Nova Scotia for almost 150 years, until the founding of the City of Halifax in 1749. It was attacked by the British six times before permanently changing hands after the Siege of Port Royal in 1710. Over the next fifty years, the French and their allies made six unsuccessful military attempts to regain the capital. Including a raid during the American Revolution, Annapolis Royal faced a total of thirteen attacks, more than any other place in North America.[5] As the site of several pivotal events during the early years of the colonisation of Canada, the historic core of Annapolis Royal was designated a National Historic Site of Canada in 1994.[6]

Geography

Annapolis Royal is situated in a good but shallow harbour[2] at the western end of the fertile Annapolis Valley, nestled between the North and South mountains which define the valley. The town is on south bank of the Annapolis River facing the heavily tidal Annapolis Basin. The riverside forms the waterfront for this historic town. Directly opposite Annapolis Royal on the northern bank of the river is the community of Granville Ferry. Allains Creek joins the Annapolis River at the town, defining the western side of the community. The Bay of Fundy is just over the North Mountain, 10 kilometres north of the town.

History

Port Royal

The original French year-round settlement at present-day Port Royal, known as the Habitation at Port-Royal, was established in 1605 by François Gravé Du Pont, Samuel de Champlain,[4] with and for Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Mons. (Annapolis Royal is twinned with the town of Royan in France, birthplace of Sieur de Mons.) The Port-Royal site is approximately 10 km (6.2 mi) west of present-day Annapolis Royal at the mouth of the Annapolis River on the Annapolis Basin. This initial settlement was abandoned for several years after being destroyed by British-American attackers in 1613,[4] but was significantly the first year-round European settlement in Canada. It was also likely to have been the site of the introduction of apples to Canada in 1606.[7]

In 1629 Scottish settlers, under the auspices of Sir William Alexander, established their settlement, known as Charlesfort, at the mouth of the Annapolis River (present site of Annapolis Royal). The settlement was abandoned to the French under the terms of the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1632). A second French settlement replaced the Scottish Charlesfort at present-day Annapolis Royal.[8] It was also called Port Royal and it developed into the capital of the French colony of Acadia.[2] Port-Royal under the French soon became self-sufficient and grew modestly for nearly a century, though it was subject to frequent attacks and capture by British military forces or those of its New England colonists, only to be restored each time to French control by subsequent recapture or treaty stipulations. Acadia remained in French hands throughout most of the 17th century.

Creation of Annapolis Royal

In 1710, Port Royal was captured a final time from the French at the Siege of Port Royal during Queen Anne's War, marking the British conquest of peninsular Nova Scotia.[2] The British renamed the town Annapolis Royal and Fort Anne after Queen Anne (1665–1714), the reigning monarch.[4] The Annapolis Basin, Annapolis River, Annapolis County, and the Annapolis Valley all take their name from the town. (Previously, under the French, the Annapolis River had been known as "Rivière Dauphin".)

Siege of Annapolis Royal (1711)

After success in the local Battle of Bloody Creek (1711), 600 Acadians and native warriors attempted to retake the Acadian capital. Under the leadership of Bernard-Anselme d'Abbadie de Saint-Castin they descended on Annapolis Royal and laid siege to Fort Anne. The garrison had fewer than 200 men, but the attackers had no artillery and were thus unable to make an impression on the fort.[9] They eventually dispersed, and Annapolis Royal remained in British hands for the remainder of the war.

Under the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, Acadia was formally granted to the Kingdom of Great Britain;[2] however, the vague boundary definitions saw only the peninsular part of Nova Scotia granted to Britain. The next half-century would see great turbulence as Britain and France vied for dominance in Acadia and in North America more generally. The indigenous Mi'kmaq were not a party to the treaty.

Father Rale's War

Blockade of Annapolis Royal (1722)

During Father Rale's War,[lower-alpha 1] in July 1722 the Abenaki and Miꞌkmaq attempted to create a blockade of Annapolis Royal, with the intent of starving the capital.[11] The natives captured 18 fishing vessels and prisoners from present-day Yarmouth to Canso. They also seized prisoners and vessels from the Bay of Fundy.

In response to the New England attack on Father Rale at Norridgewock in March 1722, 165 Mi'kmaq and Maliseet troops gathered at Minas to lay siege to the Lt. Governor of Nova Scotia at Annapolis Royal.[12][13] Under potential siege, in May 1722, Lieutenant Governor John Doucett took 22 Mi'kmaq hostage at Annapolis Royal to prevent the capital from being attacked.[14] Massachusetts Governor Samuel Shute declared war on the Abenaki.

New Englanders retrieved some of the vessels and prisoners after the Battle at Winnepang (Jeddore Harbour) in which thirty-five natives and five New-Englanders were killed. Other vessels and prisoners were retrieved at Malagash Harbour after a ransom was paid.[11]

Raid on Annapolis Royal (1724)

During Father Rale's War, the worst moment of the war for the capital came in early July 1724 when a group of sixty Mikmaq and Maliseets raided Annapolis Royal. They killed and scalped a sergeant and a private, wounded four more soldiers, and terrorized the village. They also burned houses and took prisoners.[15][lower-alpha 2] The British responded on July 8 by executing one of the Mi'kmaq hostages on the same spot the sergeant was killed. They also burned three Acadian houses in retaliation.[16]

As a result of the raid, three blockhouses were built to protect the town. The Acadian church was moved closer to the fort so that it could be more easily monitored.[17]

King George's War

During King George's War there were four attempts by the French, Acadians and Mi'kmaq to retake the capital of Acadia.[18]

Siege of Annapolis Royal (July 1744)

Le Loutre gathered three hundred Mi'kmaq warriors together, and they began their assault on Annapolis Royal on 12 July 1744. This was the largest gathering of Mi'kmaq warriors till then to take arms against the British. The Mi'kmaq outnumbered the New Englanders regulars by three to one. Two New England regulars were captured and scalped.[19] The assault lasted for four days, when the fort was rescued on 16 July by seventy New England soldiers arriving on board the ship Prince of Orange.[20]

Siege of Annapolis Royal (September 1744)

After spending the summer trying to recruit the assistance of Acadians, François Dupont Duvivier attacked Annapolis Royal on 8 September 1744. His force of 200 was up against 250 soldiers at the fort. The siege raged on for a week, and then Duvivier demanded the surrender of the fort. Both sides awaited reinforcements by sea. The fighting continued for a week and then two ships did arrive – from Boston, not Louisbourg. On board the ship was New England Ranger John Gorham (military officer) and 70 natives. Duvivier retreated.[21]

1745 Siege of Annapolis Royal

In May 1745, Paul Marin de la Malgue led 200 troops, together with hundreds of Mi'kmaq in another siege against Annapolis Royal. This force was twice the size of Duvivier's expedition. During this siege the English destroyed their own officers' fences, houses, and buildings that the attackers might be able to use.[22] The siege ended quickly when Marin was recalled to assist with defending the French during the Siege of Louisbourg (1745).[23]

During the 1745 siege, the Mi'kmaq and Maliseet took prisoner William Pote and some of Gorham's (Mohawk) Rangers. During his captivity, Pote wrote one of the most important captivity narratives from Acadia and Nova Scotia. While at Cobequid, Pote reported that an Acadian had remarked that the French soldiers should have "left their [the English] carcasses behind and brought their skins."[24] The following year, among other places, Pote was taken to the Maliseet village Aukpaque on the Saint John River. While at the village, Mi'kmaq from Nova Scotia arrived and, on July 6, 1745, tortured him together with a Mohawk ranger from Gorham's company named Jacob, as retribution for the killing of their family members by Gorham.[25] On July 10, Pote witnessed another act of revenge when the Mi'kmaq tortured a Mohawk ranger from Gorham's company at Meductic.[26]

1746 Siege of Annapolis Royal

Led by Ramesay, the French land forces laid siege to Annapolis Royal for twenty-three days, awaiting naval reinforcements. They never received the assistance they required from the Duc d'Anville Expedition and were forced to retreat.[27]

Seven Years' War

1755 Deportation of the Acadians

During the Expulsion of the Acadians, on 8 December 1755, 32 Acadian families, a total of 225, were deported from Annapolis Royal on the British ship Pembroke. The ship was headed for North Carolina. During the voyage, the Acadians took over the vessel. On 8 February 1756 the Acadians sailed up the Saint-John River as far as they could.[28] They there disembarked and burned their ship. A group of Maliseet met them and directed them up stream, where they joined an expanding Acadian community.[29] The Maliseet took them to one of Charles Deschamps de Boishébert et de Raffetot's refugee camps for the fleeing Acadians, which was at Beaubears Island.[30]

In December 1757, while cutting firewood near Fort Anne, John Weatherspoon was captured by Indians (presumably Mi'kmaq) and carried away to the mouth of the Miramichi River. From there he was eventually sold or traded to the French and taken to Quebec, where he was held until late in 1759 and the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, when General Wolfe's forces prevailed.[31]

American Revolution

During the American Revolution, the 84th Regiment of Foot (Royal Highland Emigrants) were stationed at Annapolis Royal to guard Nova Scotia against American Privateers. On 2 October 1778 the 84th Regiment was involved in the defeat of an American privateer at Annapolis Royal. Captain MacDonald sailed into the town only to find a large privateer ship raiding the port. He destroyed the privateer vessel, which had mounted ten carriage-guns.

Two months later, in December 1778, Captain Campbell of the 84th Regiment took seven men with him to retrieve an American privateer ship that had been abandoned on Partridge Island, New Brunswick. They brought the ship safely back to Annapolis Royal.[32]

However, in June 1780 the 84th Regiment was transferred to the Carolinas, leaving the town vulnerable to attack. The next year, on 29 August 1781, two large American privateer schooners attacked the undefended town. They imprisoned the men of the community in the fort and systematically looted houses in the town, even stealing window-glass from the church. The privateers fled when reports arrived that the militia was assembling outside the town. The only death took place when the privateers accidentally shot their own pilot. Two town residents were taken as hostages and later released on parole on promise of exchange for an American prisoner at Halifax.[33][34]

Loyalists

After the American Revolution, a flood of United Empire Loyalists arrived at Annapolis Royal. The Loyalist migration severely taxed the resources of the town for a time before many moved to found Loyalist settlements such as nearby Digby and Clementsport, while others stayed. Some, such as Anglican minister Jacob Bailey, remained in Annapolis Royal and became members of the town's elite. Many escaped slaves who fought for the British known as Black Loyalists were also part of the Loyalist migration, including Thomas Peters, a member of the Black Pioneers regiment and an important Black Loyalist leader who first arrived in Annapolis Royal before taking land near Digby. Another notable Black Loyalist was Rose Fortune who founded a freight business and policed the Annapolis Royal waterfront.[35] While many Loyalists moved from Annapolis Royal to take up lands elsewhere, others stayed and the migration brought an injection of professions and capital that strengthened the town as a regional centre beyond its status as a garrison outpost.

19th century

Owing to the extreme tidal range, relatively shallow waters of the Basin, and the small population of its hinterland, the port of Annapolis Royal—despite having a good harbour—carried on only a small trade through the 19th century.[2] Along with Granville Ferry across the river, however, it was a local centre for shipbuilding. Among the notable local mariners was Bessie Hall. Following the replacement of sailing ships by steam in the 1880s, Annapolis Royal served as a coaling station between Saint John and Boston.

The town had a minor boom in 1869 when the Windsor and Annapolis Railway arrived, with two large railway piers built along the waterfront and several factories constructed in the area. The population reached 1500 in the 1870s.[2] Incorporation as a town under the Nova Scotia Municipalities Act took place in 1893. However, the completion of the railway to Digby in 1893, followed by the creation of the Dominion Atlantic Railway to Yarmouth, shifted most of the steamship commerce to those cities as steel-hulled vessels began to require deeper and deeper waters. By 1901, Annapolis Royal's population had shrunk to 1019[3] and it became a small country town whose principal export was apples.[3]

Twentieth and twenty-first centuries

A ferry service ran from Lower St George Street across the river to Granville Ferry from the early 19th century but in 1921 a bridge was built to link the two sides of the estuary. This bridge collapsed in 1961 (luckily, with no loss of life) and was replaced by a causeway, already under construction. In 1984 this causeway became a component of the Annapolis Royal Tidal Power Generating Station.

The construction of the tidal generating station by the then-provincially owned electrical utility Nova Scotia Power Inc. was part of a pilot project to investigate this alternative method of generating electricity. To date, it is so far the only working tidal power plant in North America. The generating station has created tangible environmental changes in water and air temperatures in the area, siltation patterns in the river, and increased erosion of the river banks on both sides of the dam, but after more than three decades of operation it seems to have proved viable on the whole.

The rising tourism industry of recent decades has stimulated some commercial growth, and widespread broadband Internet availability in the town has attracted entrepreneurial residents from other parts of Canada and farther abroad. In 1984 Annapolis Royal elected the first female Black mayor in Canada, Daurene Lewis.[36]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1981 | 631 | — |

| 1986 | 631 | +0.0% |

| 1991 | 633 | +0.3% |

| 1996 | 583 | −7.9% |

| 2001 | 550 | −5.7% |

| 2006 | 444 | −19.3% |

| 2011 | 481 | +8.3% |

| 2016 | 491 | +2.1% |

| [37] | ||

In the 2016 Census of Population conducted by Statistics Canada, the Town of Annapolis Royal recorded a population of 491 living in 294 of its 346 total private dwellings, a change of 2.1% from its 2011 population of 481. With a land area of 2.04 km2 (0.79 sq mi), it had a population density of 240.7/km2 (623.4/sq mi) in 2016.[1]

Theatre

The Annapolis Basin in Nova Scotia served as the cradle for both French and English language theatre in Canada.[38] Le Théâtre de Neptune, a pageant written by Marc Lescarbot for performance at the Port-Royal Habitation in 1606, was the first European theatre production in North America. The tradition of English theatre in Canada, also started at Annapolis Royal. The tradition at Fort Anne, Nova Scotia, was to produce a play in honour of the Prince of Wales's birthday. Prior to Paul Mascarene's productions, the Boston Gazette (4–11 June 1733) reported that George Farquhar's The Recruiting Officer was produced on Saturday, 20 January 1733 by the officers of the garrison to mark the Prince's birthday. Paul Mascarene translated Molière's La Misanthrope and then staged at least two productions of the work during the winter of 1743-1744. The second performance on 20 January 1744 had also coincided with celebrations in the colony to mark the birthday of Frederick, Prince of Wales. The text of the first three acts is contained in the Mascarene papers, British Library. And four years after the Mascarene production, on 20 January 1748, Major Phillips and Captain Floyer also produced a play in honour of the Prince's birthday. Unfortunately, the Boston News Letter (3 March 1748) fails to indicate the title of the play. It does reveal, however, that the same play was staged a second time on 2 February 1748, at the request of Captain Winslow, after the colony received the news of Admiral Edward Hawke's success Second Battle of Cape Finisterre (1747), in October 1747.[39]

Notable people

- Joseph Broussard, also known as "Beausoleil", an Acadian leader who fought a guerilla war against the British during the Expulsion of the Acadians, born in 1702 in Port Royal

- Sir William Williams, 1st Baronet, of Kars, born at Annapolis Royal[40]

- Sir William Winniett, abolitionist, British Governor

- Noel Doiron, born at Port Royal

- Rose Fortune, first female police officer in Canada

- Daurene Lewis, first black woman mayor in Canada, recipient of Order of Canada

- Thomas Peters (revolutionary)

- Charlotte Elizabeth Tonna

- John Bradstreet, British officer who fought in King George's War and Seven Years' War

- William Johnstone Ritchie

- Robert Knox Sneden, American Civil War veteran

- Erasmus James Philipps, Battle of Grand Pre

- John William Ritchie, Father of Confederation

Climate

| Climate data for Annapolis Royal (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18.5 (65.3) |

17.5 (63.5) |

21.7 (71.1) |

26.0 (78.8) |

30.0 (86.0) |

34.0 (93.2) |

32.2 (90.0) |

32.8 (91.0) |

30.0 (86.0) |

25.6 (78.1) |

22.2 (72.0) |

19.4 (66.9) |

34.0 (93.2) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −0.7 (30.7) |

0.1 (32.2) |

3.4 (38.1) |

9.0 (48.2) |

15.8 (60.4) |

20.4 (68.7) |

23.3 (73.9) |

23.3 (73.9) |

19.0 (66.2) |

13.2 (55.8) |

8.0 (46.4) |

2.1 (35.8) |

11.4 (52.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −4.3 (24.3) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

5.1 (41.2) |

11.1 (52.0) |

15.5 (59.9) |

18.5 (65.3) |

18.6 (65.5) |

14.9 (58.8) |

9.6 (49.3) |

4.9 (40.8) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

7.4 (45.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −7.8 (18.0) |

−7.6 (18.3) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

1.2 (34.2) |

6.2 (43.2) |

10.2 (50.4) |

13.3 (55.9) |

13.4 (56.1) |

10.3 (50.5) |

5.9 (42.6) |

1.7 (35.1) |

−4.1 (24.6) |

3.2 (37.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −26.0 (−14.8) |

−27.2 (−17.0) |

−24.4 (−11.9) |

−13.3 (8.1) |

−6.1 (21.0) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−8.3 (17.1) |

−13.3 (8.1) |

−23.9 (−11.0) |

−27.2 (−17.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 114.4 (4.50) |

85.2 (3.35) |

94.3 (3.71) |

94.7 (3.73) |

86.4 (3.40) |

74.4 (2.93) |

68.7 (2.70) |

68.5 (2.70) |

110.3 (4.34) |

120.4 (4.74) |

125.3 (4.93) |

112.5 (4.43) |

1,155.2 (45.48) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 59.5 (2.34) |

51.6 (2.03) |

67.0 (2.64) |

87.0 (3.43) |

86.0 (3.39) |

74.4 (2.93) |

68.7 (2.70) |

68.5 (2.70) |

110.3 (4.34) |

120.4 (4.74) |

118.0 (4.65) |

80.2 (3.16) |

991.8 (39.05) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 54.9 (21.6) |

33.5 (13.2) |

27.3 (10.7) |

7.7 (3.0) |

0.4 (0.2) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

7.3 (2.9) |

31.2 (12.3) |

162.4 (63.9) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 13.7 | 10.9 | 11.3 | 11.3 | 11.0 | 11.1 | 8.6 | 8.3 | 10.2 | 11.2 | 13.2 | 12.9 | 133.5 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 6.1 | 5.5 | 7.6 | 10.4 | 10.9 | 11.1 | 8.6 | 8.3 | 10.2 | 11.2 | 12.4 | 8.5 | 110.7 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 9.2 | 6.4 | 5.0 | 1.7 | 0.05 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 5.2 | 28.9 |

| Source: Environment Canada[41] | |||||||||||||

Economy

Historic places

Tourism is a significant part of the economy of Annapolis Royal. Fort Anne, contained within the boundaries of the town, was initially designated a National Historic Park in 1917 and then a National Historic Site in 1920.[42] The French fort was renamed Fort Anne and established as a British garrison. The fort, built originally around 1703, was designed to defend the capital of Acadia/ Nova Scotia from seaward attack. Today, much of the original earthen embankments may be visited, as well as some buildings original to the military facility and the Garrison Cemetery. This is the oldest formal cemetery in Canada, dating back to the French and later the British. The oldest English gravestone in Canada is among the graves, that of Bathiah Douglas who was buried in 1720.[43] (Rose Fortune, a Black Loyalist and the first female police officer in what is now Canada is buried here.)

In addition to the town's historic district and Fort Anne, the Annapolis County Court House, the site of Charles Fort, and the Sinclair Inn/Farmer's Hotel are also each individually designated as National Historic Sites.[44][45][46]

The trains of the Dominion Atlantic Railway, running from Halifax to Yarmouth, were suddenly shut down in 1990 and the track removed, bringing much industrial commerce within the confines of Nova Scotia's smallest town to a halt. Today, after many years of neglect, the old brick railway station has been privately renovated into professional office space.

The fleet of scallop boats using the Annapolis Basin as a base continue to generate millions of dollars of economic activity each year and support many businesses in the Annapolis Royal area. The "haul-up" beside the Government Wharf (recently divested by the federal government to the local citizenry) continues to overhaul and refurbish many scallop boats every year.

The town also contains the largest registered Historic District in Canada, as well as a waterfront boardwalk, a variety of unique shops, and a picturesque landscape. Visitors can enjoy a fine selection of inns, bed-&-breakfast, and hotel accommodations, as well as the Annapolis Royal Historic Gardens (established in 1986), many shops and galleries, including Westside Studio, the Lucky Rabbit Pottery, and Catfish Moon. There is a very lively Annapolis Region Community Arts Council gallery at ArtSpace, and King's Theatre offers both live and motion-picture entertainment regularly. Every Saturday morning there is a Farmers Market (summers at the Market Square), off-season at the Historic Gardens.

The town also offers various historical walking-tours. During the summer, late-night, guided candlelight Garrison Cemetery tours are available and very popular. An added benefit is the scenery of the surrounding countryside, much of which is agricultural. The mild climate and scenic location make this a favourite destination in all seasons. Nova Scotia's largest amusement park, Upper Clements Park and Adventure Park, is west of the town in nearby Upper Clements.

The town, along with most of Annapolis and Digby counties, experienced a severe economic decline during the mid-1990s after a nearby military training base, CFB Cornwallis, was closed as a result of Government of Canada budget cuts. The former base located on the shores of the Annapolis Basin was formerly the site of the Pearson Peacekeeping Centre, but this too was closed by the federal government after a decade of successful operation with international participants from over 130 countries. It is now the home of the Annapolis Basin Conference Centre and an industrial park for small businesses. The HMCS Acadia sea-cadets camp is held there every summer.

Power generation

The Annapolis Royal Generating Station is tidal power station located on the Annapolis River immediately upstream from the town of Annapolis Royal. The only tidal generating station in North America, it produces 20 MW twice daily with the change in tides. The generating station harnesses the tidal difference created by the large tides in the Annapolis Basin, a sub-basin of the Bay of Fundy. It opened in 1984.

Eponym

Asteroid 516560 Annapolisroyal was named in honor of the town.[47] The official naming citation was published by the Minor Planet Center on 25 September 2018 (M.P.C. 111804).[48]

References

- Notes

- Citations

- "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, and census subdivisions (municipalities), 2016 and 2011 censuses – 100% data (Nova Scotia)". Statistics Canada. February 8, 2017. Retrieved February 12, 2017.

-

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 64.

- Harris, Carolyn (Aug 2017). "The Queen's land". Canada's History. 97 (4): 34–43. ISSN 1920-9894.

- Dunn (2004), p. viii.

- Annapolis Royal Historic District. Canadian Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- "Canadian food firsts". Canadian Geographic. January–February 2002. Archived from the original on 24 June 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- Allen, Robert S. (March 4, 2015) [February 7, 2006]. "Fort Anne". The Canadian Encyclopedia (online ed.). Historica Canada.

- Faragher (2005), p. 135.

- Grenier (2008).

- Murdoch, Beamish (1865). A History of Nova-Scotia, Or Acadie. Vol. I. Halifax: J. Barnes. p. 399.

- Grenier (2008), p. 56

• Grenier, John (2005). The First Way of War: American War Making on the Frontier, 1607–1814. Cambridge University Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-139-44470-5. - Brodhead, John Romeyn (1855). Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York. Vol. IX. Albany: Weed, Parsons and Co. p. 936.

- Grenier (2008), p. 56.

- Faragher (2005), pp. 164-165

• Murdoch, Beamish (1865). A History of Nova-Scotia, Or Acadie. Vol. I. Halifax: J. Barnes. pp. 408–409. - Dunn (2004), p. 123.

- Dunn (2004), pp. 124-125.

- Griffiths (2005), pp. 338-371.

- Grenier (2008), pp. 110-111.

- Griffiths (2005), p. 338.

- Griffiths (2005), pp. 338-341.

- Dunn (2004), p. 157.

- Griffiths (2005), p. 351.

- Pote, William (1895). The Journal of Captain William Pote, Jr., During his Captivity in the French and Indian War from May, 1745, to August, 1747. New York: Dodd, Mead & Co. p. 34.

- Raymond, p. 42-43

- Raymond, p. 45

- Griffiths (2005), p. 359.

- Delaney, Paul (January–June 2004). "La reconstitution d'un rôle des passagers du Pembroke" [The Reconstructed of a List of Passengers of the Pembroke] (PDF). Les Cahiers (in French). La Societe historique acadienne. 35 (1&2): 4–75.

- Plank, Geoffrey (2001). An Unsettled Conquest: The British Campaign Against the Peoples of Acadia. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-8122-0710-1.

- Grenier (2008), p. 186.

- "Journal of John Witherspoon". Collections of the Nova Scotia Historical Society. Volume II. Nova Scotia Historical Society. 1881. pp. 31–62.

- Stacy, Kim (1994). No One harms me with impunity - the History, Organization and Biographies of the 84th Highland Regiment (Royal Highland Emigrants) and Young Royal Highlanders during the Revolutionary War 1775-1784. Unpublished manuscript. p. 31.

- Dunn (2004), pp. 222-223.

- Faibisy, John Dewar (1972). Privateering and piracy : the effects of New England raiding upon Nova Scotia during the American Revolution, 1775-1783 (Doctoral Dissertation). University of Massachusetts Amherst. p. 185.

- Ian Lawrence, Historic Annapolis Royal, Halifax: Nimbus Publishing (2002), p. ix, p. 26

- Daurene Lewis, first black female mayor in Canada, dies", CBC News, Jan 26, 2013

- "I:\ecstats\Agency\BRIAN\census2" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-05. Retrieved 2010-01-20.

- David Gardner's thesis, "An Analytic History of the Theatre in Canada: the European Beginnings to 1760," and his article "British Garrison Theatre in Canada during the French Regime"

- http://journals.hil.unb.ca/index.php/tric/article/view/12655/13542

- "The most distinguished native of Annapolis Royal living in the nineteenth century was the Hon Sir William Williams, Bart, known from his distinguished services in the Crimean war as the 'hero of Kars'." "Full text of 'Chapters in the history of Halifax, Nova Scotia: Rhode Island Settlers in Hants County, Nova Scotia: Alexander McNutt the Colonizer'", p. 413.

- "Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- Fort Anne National Historic Site of Canada. Canadian Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- Deborah Trask, Life How Short, Eternity How Long: Gravestone Carving and Carvers in Nova Scotia, Halifax: Nova Scotia Museum, 1978, p. 11

- Annapolis County Court House. Canadian Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- Charles Fort. Canadian Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- Sinclair Inn/Farmer's Hotel. Canadian Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- "516560 Annapolisroyal (2006 XL67)". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- "MPC/MPO/MPS Archive". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- References

- Dunn, Brenda (2004). A History of Port-Royal-Annapolis Royal, 1605-1800. Nimbus. ISBN 978-1-55109-740-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Faragher, John Mack (2005). A Great and Noble Scheme: The Tragic Story of the Expulsion of the French Acadians from Their American Homeland. W.W Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-05135-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)* Grenier, John (2008). The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710-1760. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3876-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Griffiths, N.E.S. (2005). From Migrant to Acadian: A North American Border People, 1604-1755. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-2699-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Grenon, Jean-Yves. Pierre Dugua de Mons: Fondateur de l'Acadie (1604-5), Co-Fondateur de Québec (1608); Pierre Dugua de Mons: Founder of Acadie (1604-5), Co-Founder of Québec (1608) (English translation by Phil Roberts). Annapolis Royal: Peninsular Press, 2000.

- Lawrence, Ian. Historic Annapolis Royal: Images of Our Past. Halifax: Nimbus, 2002.

- Reid, John, Maurice Basque, Elizabeth Mancke, Barry Moody, Geoffrey Plank, and William Wicken. The 'Conquest' of Acadia, 1710: Imperial, Colonial, and Aboriginal Constructions. 2004.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Annapolis Royal. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Annapolis, Canada. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Annapolis Royal. |