Fortress of Louisbourg

The Fortress of Louisbourg (French: Forteresse de Louisbourg) is a National Historic Site of Canada and the location of a one-quarter partial reconstruction of an 18th-century French fortress at Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia. Its two sieges, especially that of 1758, were turning points in the Anglo-French struggle for what today is Canada.[1]

| Fortress of Louisbourg | |

|---|---|

| Native name French: Forteresse de Louisbourg | |

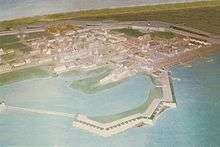

Diorama of the Fortress of Louisbourg in 1758 | |

| Location | 259 Park Service Rd, Louisbourg, Nova Scotia, Canada B1C 2L2 |

| Coordinates | 45.892382°N 59.986210°W |

| Built | 1713–1740 |

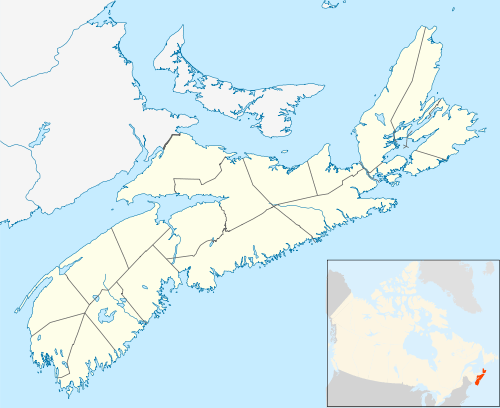

Location of Fortress of Louisbourg in Nova Scotia | |

| Official name | Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Site |

| Designated | 30 January 1920 |

The original settlement was made in 1713, and initially called Havre à l'Anglois. Subsequently, the fishing port grew to become a major commercial port and a strongly defended fortress. The fortifications eventually surrounded the town. The walls were constructed mainly between 1720 and 1740. By the mid-1740s Louisbourg, named for Louis XIV of France, was one of the most extensive (and expensive) European fortifications constructed in North America.[2] It was supported by two smaller garrisons on Île Royale located at present-day St. Peter's and Englishtown. The Fortress of Louisbourg suffered key weaknesses, since it was erected on low-lying ground commanded by nearby hills and its design was directed mainly toward sea-based assaults, leaving the land-facing defences relatively weak. A third weakness was that it was a long way from France or Quebec, from which reinforcements might be sent. It was captured by British colonists in 1745, and was a major bargaining chip in the negotiations leading to the 1748 treaty ending the War of the Austrian Succession. It was returned to the French in exchange for border towns in what is today Belgium. It was captured again in 1758 by British forces in the Seven Years' War, after which its fortifications were systematically destroyed by British engineers.[2] The British continued to have a garrison at Louisbourg until 1768.

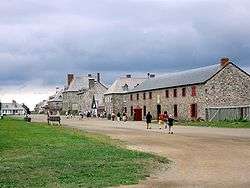

The fortress and town were partially reconstructed in the 1960s and 1970s, using some of the original stonework, which provided jobs for unemployed coal miners. The head stonemason for this project was Ron Bovaird. The site is operated by Parks Canada as a living history museum. The site stands as the largest reconstruction project in North America.[3]

History

French settlement on Île Royale (now Cape Breton Island) can be traced to the early 17th century following settlements in Acadia that were concentrated on Baie Française (now the Bay of Fundy) such as at Port-Royal and other locations in present-day peninsular Nova Scotia. A French settlement at Sainte Anne (now Englishtown) on the central east coast of Île Royale was established in 1629 and named Fort Sainte Anne, lasting until 1641. A fur trading post was established on the site from 1651–1659, but Île Royale languished under French rule as attention was focused on the St. Lawrence River/Great Lakes colony of Canada (which then comprised parts of what is now Quebec, Ontario, Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, Wisconsin and Illinois), Louisiana (which encompassed the current Mississippi Valley states and part of Texas), and the small agricultural settlements of mainland Acadia.

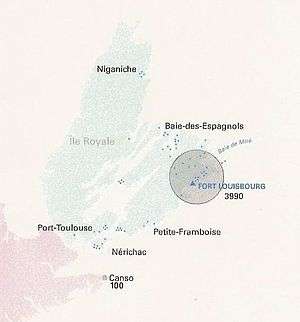

The Treaty of Utrecht in 1713 gave Britain control of part of Acadia (peninsular Nova Scotia) and Newfoundland; however, France maintained control of its colonies at Île Royale, Île Saint-Jean (now Prince Edward Island), Canada and Louisiana, with Île Royale being France's only territory directly on the Atlantic seaboard (which was controlled by Britain from Newfoundland to present-day South Carolina) and it was strategically close to important fishing grounds on the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, as well as being well placed for protecting the entrance to the Gulf of St. Lawrence.[2]

In 1713, France set about constructing Port Dauphin and a limited naval support base at the former site of Fort Sainte-Anne; however, the winter icing conditions of the harbour led the French to choose another harbour on the southeastern part of Île Royale. The harbour, being ice-free and well protected, soon became a winter port for French naval forces on the Atlantic seaboard and they named it Havre Louisbourg after King Louis XIV.

First siege

The Fortress was besieged in 1745 by a New England force backed by a Royal Navy squadron. The New England attackers succeeded when the fortress capitulated on June 16, 1745. A major expedition by the French to recapture the fortress led by Jean-Baptiste de La Rochefoucauld de Roye, duc d'Anville, the following year was destroyed by storms, disease and British naval attacks before it ever reached the fortress.

Louisbourg returned

In 1748, the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, which ended the War of the Austrian Succession, restored Louisbourg to France in return for territory gained in the Austrian Netherlands and the British trading post at Madras in India. Maurepas, the ministre de la marine, was determined to have it back. He regarded the fortified harbour as essential to maintaining French dominance in the fisheries of the area. The disgust of the French in this transaction was matched by that of the English colonists. The New England forces left, taking with them the famous Louisbourg Cross, which had hung in the fortress chapel. This cross was rediscovered in the Harvard University archives only in the latter half of the 20th century; it is now on long-term loan to the Louisbourg historic site.

Having given up Louisbourg, Britain in 1749 created its own fortified town on Chebucto Bay which they named Halifax. It soon became the largest Royal Navy base on the Atlantic coast and hosted large numbers of British army regulars. The 29th Regiment of Foot was stationed there; they cleared the land for the port and settlement.

Second siege

Britain's American colonies were expanding into areas claimed by France by the 1750s, and the efforts of French forces and their Indian allies to seal off the westward passes and approaches through which American colonists could move west soon led to the skirmishes that developed into the French and Indian War in 1754. The conflict widened into the larger Seven Years' War by 1756, which involved all of the major European powers.

A large-scale French naval deployment in 1757 fended off an attempted assault by the British in 1757. However, inadequate naval support the following year allowed a large British combined operation to land for the 1758 Siege of Louisbourg which ended after a siege of six weeks on 26 July 1758, with a French surrender.[4] The fortress was used by the British as a launching point for its 1759 Siege of Quebec that culminated in the Battle of the Plains of Abraham.

The fortifications at Louisbourg were systematically destroyed by British engineers in 1760 to prevent the town and port from being used in the future by the French, should the peace process return Cape Breton island to France. The British kept a garrison at Louisbourg until 1768.[5] Some of the cut-stones from Louisbourg were shipped to Halifax to be re-used and, in the 1780s, to Sydney, Nova Scotia.

20th century

The site of the fortress was designated a National Historic Site in 1920.[6] Beginning in 1961, the government of Canada undertook a historical reconstruction of one quarter of the town and fortifications with the aim being to recreate Louisbourg as it would have been at its height in the 1740s. The work required an interdisciplinary effort by archeologists, historians, engineers, and architects. The reconstruction was aided by unemployed coal miners from the industrial Cape Breton area, many of whom learned French masonry techniques from the 18th century and other skills to create an accurate replica. Where possible, many of the original stones were used in the reconstruction.

Dozens of researchers worked on the project over a span of five decades. They included British-born archeologists Bruce W. Fry and Charles Lindsay; and Canadian historians B. A. Balcom, Kenneth Donovan, Brenda Dunn, John Fortier, Margaret Fortier, Allan Greer, A.J.B. Johnston, Eric Krause, Anne Marie Lane Jonah, T.D. MacLean, Christopher Moore, Robert J. Morgan, Christian Pouyez and Gilles Proulx. There were many more. Among the architects, Yvon LeBlanc, one of the first Acadian architects, was responsible for most of the town-site buildings, with input from researchers who contributed to various committees.

.jpg)

Today, the entire site of the fortress, including the one-quarter reconstruction, is the Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Site of Canada, operated by Parks Canada. Offerings include guided and unguided tours, and the demonstration and explanation of period weapons, including muskets and a cannon. Puppet shows are also shown. The Museum / Caretakers Residence (ca. 1935-6) within the site is a Classified Federal Heritage Building.[7] The fortress has also greatly aided the local economy of the town of Louisbourg, as it has struggled to diversify economically with the decline of the North Atlantic fishery.

On 5 May 1995, Canada Post issued the 'Fortress of Louisbourg' series to mark the 275th anniversary of the official founding of the fortress, the 250th anniversary of the siege by the New Englanders, the 100th anniversary of the commemoration by the Society of Colonial Wars, and the 100th anniversary of the arrival of the Sydney and Louisburg Railway (S & L). The Fortress of Louisbourg series includes: 'The Harbour and Dauphin Gate',[8] '18th Century Louisbourg';[9] 'The King's Bastion';[10] 'The King's Garden, Convent, Hospital, and British Barracks'[11] and 'The Fortifications and Ruins Fronting the Sea and Rochfort Point'[12] The 43¢ stamps were designed by Rolf P. Harder.

The museum that operates from the Fortress is affiliated with: CMA, CHIN, and Virtual Museum of Canada.

Fortified town

The Fortress of Louisbourg was the capital for the colony of Île-Royale,[13] and was located on the Atlantic coast of Cape Breton Island near its southeastern point. The location for the fortress was chosen because it was easy to defend against British ships attempting to either block or attack the St. Lawrence River, at the time the only way to get goods to Canada and its cities of Quebec and Montreal. South of the fort, a reef provided a natural barrier, while a large island provided a good location for a battery. These defences forced British ships to enter the harbour via a 500-foot (150 m) channel. The fort was built to protect and provide a base for France's lucrative North American fishery and to protect Quebec City from British invasions.[14] For this reason, it has been given the nicknames ‘Gibraltar of the North’ or the ‘Dunkirk of America.’ The fort was also built to protect France's hold on one of the richest fishing grounds in the world, the Grand Banks. One hundred and sixteen men, ten women, and twenty-three children originally settled in Louisbourg.[15]

Demographic

The population of Louisbourg quickly grew. In 1719, 823 people called this maritime city their home. Seven years later, in 1726, the population was 1,296, in 1734 it was 1,616, and by 1752, the population of Louisbourg was 4,174.[16] Of course, population growth did not come without consequences. Smallpox ravaged the population in 1731 and 1732,[17] but Louisbourg continued to grow, especially economically.

| Year | Inhabitants |

|---|---|

| 1719 | 823 |

| 1726 | 1 296 |

| 1734 | 1 616 |

| 1737 | 2 023 |

| 1740 | 2 500 |

| 1745 | 3 000 |

| 1750 | 3 990 |

| 1752 | 4 174 |

Economy

.jpg)

Louisbourg was a large enough city to have a commercial district, a residential district, military arenas, marketplaces, inns, taverns and suburbs, as well as skilled labourers to fill all of these establishments.[19]:3 For the French, it was the second most important stronghold and commercial city in New France. Only Quebec was more important to France.[20]

Unlike most other cities in New France, Louisbourg did not rely on agriculture or the seigneurial system.[13] Louisbourg itself was a popular port and was the third busiest port in North America (after Boston and Philadelphia.)[21] It was also popular for its exporting of fish, and other products made from fish, such as cod-liver oil. The North Atlantic fishing trade employed over ten thousand people, and Louisbourg was seen as the ‘nursery for seamen.’ Louisbourg was an important investment for the French government because it gave them a strong commercial and military foothold in the Grand Banks. For France, the fishing industry was more lucrative than the fur trade.[22] In 1731, Louisbourg fishermen exported 167,000 quintals of cod and 1600 barrels of cod-liver oil. There were roughly 400 shallop-fishing vessels out each day vying for the majority of the days catch. Also, 60 to 70 ocean-going schooners would head out from Louisbourg to catch fish further down the coast.[23] Louisbourg's commercial success was able to bring ships from Europe, The West Indies, Quebec, Acadia, and New England.[21]

Fortifications

.jpg)

Louisbourg was also known for its fortifications, which took the original French builders 28 years to complete. The engineer behind the project was Jean-Francois du Vergery de Verville. Verville picked Louisbourg as his location because of its natural barriers.[24] The fort itself cost France 30 million French livres, which prompted King Louis XV to joke that he should be able to see the peaks of the buildings from his Palace in Versaille.[25] The original budget for the fort was four million livres.[26] Two and a half miles of wall surrounded the entire fort. On the western side of the fort, the walls were 30 feet (9.1 m) high, and 36 feet (11 m) across, protected by a wide ditch and ramparts.

The city had four gates that led into the city. The Dauphin Gate, which is currently reconstructed, was the busiest, leading to the extensive fishing compounds around the harbour and to the main road leading inland. The Frederick Gate, also reconstructed, was the waterfront entrance. The Maurepas Gate, facing the narrows, connected the fishing establishments, dwellings and cemeteries on Rocheford Point and was elaborately decorated as it was very visible to arriving ships. The Queen's Gate on the sparsely populated seaward side saw little use. Louisbourg was also home to six bastions, two of which have been reconstructed: the Dauphin bastion, commonly referred to as a 'demi-bastion' because of its modification; the King's bastion; the Queen's bastion; the Princess bastion; the Maurepas bastion; and the Brouillon bastion. On the eastern side of the fort, 15 guns pointed out to the harbour. The wall on this side was only 16 feet (4.9 m) high and 6 feet (1.8 m) across.

.jpg)

Louisbourg was one of the "largest military garrisons in all of New France", and many battles were fought and lives lost here because of it.[19]:3 The fort had the embrasures to mount 148 guns; however, historians have estimated that only 100 embrasures had cannons mounted. Disconnected from the main fort, yet still a part of Louisbourg, a small island in the harbour entrance was also fortified. The walls on the Island Battery were 10 feet (3.0 m) high, and 8 feet (2.4 m) thick. Thirty-one 24-pound guns were mounted facing the harbour. The island itself was small, with room for only a few small ships to dock there.[27] An even larger fortified battery, the Royal Battery, was located across the harbour from the town and mounted 40 guns to protect the harbour entrance.

Structures

The Louisbourg hospital was the finest hospital in North America and the second-largest building in the fort town.[28][29] The hospital had a tall spire that would rival that of the King's bastion and was run by the Brothers of Saint-Jean-de-Dieu.[30]

Climate

Louisbourg experiences a marine influenced humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dfb).

| Climate data for Fortress of Louisbourg, 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1972–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 14.0 (57.2) |

13.0 (55.4) |

26.0 (78.8) |

19.0 (66.2) |

29.0 (84.2) |

31.7 (89.1) |

31.0 (87.8) |

32.0 (89.6) |

31.5 (88.7) |

25.0 (77.0) |

20.0 (68.0) |

13.5 (56.3) |

32.0 (89.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −1 (30) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

1.4 (34.5) |

5.6 (42.1) |

11.0 (51.8) |

16.4 (61.5) |

20.3 (68.5) |

21.4 (70.5) |

18.3 (64.9) |

12.5 (54.5) |

7.0 (44.6) |

2.3 (36.1) |

9.5 (49.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −4.9 (23.2) |

−5.2 (22.6) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

2.2 (36.0) |

6.9 (44.4) |

11.9 (53.4) |

16.2 (61.2) |

17.6 (63.7) |

14.3 (57.7) |

8.9 (48.0) |

3.8 (38.8) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

5.7 (42.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −8.9 (16.0) |

−9.3 (15.3) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

2.7 (36.9) |

7.4 (45.3) |

12.2 (54.0) |

13.8 (56.8) |

10.3 (50.5) |

5.2 (41.4) |

0.6 (33.1) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

1.9 (35.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −26 (−15) |

−25 (−13) |

−23 (−9) |

−13.5 (7.7) |

−7 (19) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

4.0 (39.2) |

3.5 (38.3) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

−12 (10) |

−20.6 (−5.1) |

−26 (−15) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 147.0 (5.79) |

138.0 (5.43) |

143.6 (5.65) |

147.5 (5.81) |

127.6 (5.02) |

113.1 (4.45) |

108.4 (4.27) |

107.8 (4.24) |

133.0 (5.24) |

158.3 (6.23) |

168.9 (6.65) |

153.1 (6.03) |

1,646.3 (64.81) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 83.4 (3.28) |

77.9 (3.07) |

100.1 (3.94) |

127.9 (5.04) |

126.9 (5.00) |

113.1 (4.45) |

108.4 (4.27) |

107.8 (4.24) |

133.0 (5.24) |

158.3 (6.23) |

160.7 (6.33) |

106.3 (4.19) |

1,403.6 (55.26) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 58.5 (23.0) |

56.6 (22.3) |

41.2 (16.2) |

17.9 (7.0) |

0.8 (0.3) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

8.2 (3.2) |

44.6 (17.6) |

227.8 (89.7) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 15.4 | 13.3 | 13.7 | 15.3 | 15.2 | 14.0 | 13.9 | 14.3 | 15.2 | 16.8 | 18.9 | 17.8 | 183.8 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 8.3 | 7.2 | 9.6 | 13.6 | 15.1 | 14.0 | 13.9 | 14.3 | 15.2 | 16.8 | 17.5 | 11.9 | 157.3 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 9.3 | 8.0 | 6.3 | 3.1 | 0.24 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.2 | 8.0 | 37.1 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 89.9 | 109.0 | 138.4 | 150.7 | 170.7 | 185.5 | 184.7 | 182.1 | 159.8 | 130.9 | 74.9 | 74.2 | 1,650.7 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 31.9 | 37.3 | 37.5 | 37.2 | 36.9 | 39.5 | 38.8 | 41.6 | 42.4 | 38.6 | 26.2 | 27.4 | 36.3 |

| Source: Environment Canada[31][32][33] | |||||||||||||

References

- Johnston, A. J. B. (2013). Louisbourg: Past, Present, Future. Halifax, Nova Scotia: Nimbus. ISBN 978-1-771080-52-1.

- Harris, Carolyn (Aug 2017). "The Queen's land". Canada's History. 97 (4): 34–43. ISSN 1920-9894.

- National Geographic Guide to the National Parks of Canada, 2nd Edition. National Geographic Society. 2016. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-4262-1756-2.

- Johnston, A.J.B. (2007). Emdgame 1758: The Promise, the Glory and the Despair of Louisbourg's Last Decade. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press.

- Johnston, A.J.B. (2013). Louisbourg:Past, Present, Future. Halifax, Nova Scotia: Nimbus. ISBN 978-1-771080-52-1.

- Fortress of Louisbourg. Canadian Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- Museum / Caretakers Residence. Canadian Register of Historic Places.

- Harbour and Dauphin Gate'

- '18th Century Louisbourg' Canada Post stamp

- 'The King's Bastion'

- King's Garden, Convent, Hospital, and British Barracks'

- Fortifications and Ruins Fronting the Sea and Rochfort Point

- John Fortier, p. 4

- Robert Emmet Wall. "Louisbourg ,1745" in The New England Quarterly, Vol. 37, No. 1 (March 1964), page 64 – 65.

- A.J.B Johnston. "From Port de peche to ville fortifiee: The Evolution of Urban Louisbourg 1713–1858" in Aspects of Louisbourg. The University College of Cape Breton Press, Sidney Nova Scotia 1995, page 4

- B.A. Balcom. "The Cod Fishery of Isle Royale, 1713-58" in Aspects of Louisbourg. The University College of Cape Breton Press, Sidney Nova Scotia 1995, page 171

- Christopher Moore, Louisbourg Portraits, Toronto, Ontario: McClelland and Stewart Ltd, 2000

- Recensements d'Acadie (1671-1752), Archives des Colonies, Série G1, vol. 466-1, p 228.

- "The Fortress of Louisbourg and its Cartographic Evidence". Bulletin of the Association for Preservation Technology. 4 (1): 3–40. 1972. doi:10.2307/1493360. JSTOR 1493360.

- R.H Whitbeck. "A Geographical Study of Nova Scotia" in Bulletin of the American Geographical Society, Vol. 46, No. 6 (1914), page 413.

- Fortier, p. 3

- A.J.B Johnston. "From Port de peche to ville fortifiee: The Evolution of Urban Louisbourg 1713–1858" in Aspects of Louisbourg. The University College of Cape Breton Press, Sidney Nova Scotia 1995, page 4

- Christopher Moore, Louisbourg Portraits, Toronto, Ontario: McClelland and Stewart Ltd, 2000, page 109, 261-270.

- An Appearance of Strength The Fortification of Louisbourg by Bruce W. Fry pg 20

- Fortier, p. 11

- B.A. Balcom. "The Cod Fishery of Isle Royale, 1713-58" in Aspects of Louisbourg. The University College of Cape Breton Press, Sidney Nova Scotia 1995, page 171.

- Christopher Moore, Louisbourg Portraits, Toronto, Ontario: McClelland and Stewart Ltd, 2000, page 66.

- "Fortress America: The Forts That Defended America, 1600 to the Present - J. E. Kaufmann, H. W. Kaufmann - Google Books". Books.google.ca. Retrieved 2016-10-29.

- From copy of JS McLennan's speech at the unveiling of the Kennington Cove held by the Cape Breton Regional Library, Louisbourg Collection, Drawer 2, File L, p.12.

- "Louisbourg: The Novel - Guy Wendell Hogue - Google Books". Books.google.ca. Retrieved 2016-10-29.

- "Louisbourg, Nova Scotia". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- "Louisbourg, Nova Scotia". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- "Daily Data Report for March 2012". Canadian Climate Data. Environment Canada. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

Further reading

- Olive Patricia and Hoad, Linda M. Louisbourg et les Indiens : une étude des relations raciales de la France, 1713-1760

- Drake, Samuel Adams (1891). The Taking of Louisburg 1745. Boston: Lee and Shepard Publishers. (reprinted by Kessinger Publishing ISBN 978-0-548-62234-6)

- Fortier, John (1979). Fortress of Louisbourg. Toronto: Oxford University Press.

- Johnston, A.J.B (2008). Endgame 1758: The Promise, the Glory and the Despair of Louisbourg's Last Decade Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press and Sydney: Cape Breton University Press, 2007.

- Johnston, A.J.B. (2001). "Control and Order: The Evolution of French Colonial Louisbourg, 1713-1758" East Lansing: Michigan State University Press.

- Johnston, A.J.B. (1996). "Life and Religion at Louisbourg, 1713-1758" Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queens University Press.

- Johnston, A.J.B. (2013). Louisbourg: Past, Present, Future. Halifax: Nimbus Publishing. ISBN 978-1-771080-52-1.

- Johnston, A.J.B. (1997). "Louisbourg: The Phoenix Fortress" Halifax: Nimbus Publishing.

- Johnston, A.J.B. (2002). "The Summer of 1744: A Portrait of Life in 18th-Century Louisbourg" Ottawa: Parks Canada.

- McLennan, J.S (2000, originally 1918). Louisbourg: From its Foundation to its Fall, 1713-1758. Halifax: The Book Room Limited.

- Parks Canada (undated). Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Site brochure.

- Wood, William. The Great Fortress: A Chronicle of Louisbourg 1720–1760 (text version from Project Gutenberg, audiobook from LibriVox)