Francis I of France

Francis I (French: François Ier; Middle French: Francoys; 12 September 1494 – 31 March 1547) was King of France from 1515 until his death in 1547. He was the son of Charles, Count of Angoulême, and Louise of Savoy. He succeeded his first cousin once removed and father-in-law Louis XII, who died without a son.

| Francis I | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Jean Clouet, c. 1530 | |

| King of France | |

| Reign | 1 January 1515 – 31 March 1547 |

| Coronation | 25 January 1515 |

| Predecessor | Louis XII |

| Successor | Henry II |

| Born | 12 September 1494 Château de Cognac, Cognac, France |

| Died | 31 March 1547 (aged 52) Château de Rambouillet, France |

| Burial | 23 May 1547 Basilica of St Denis, France |

| Spouse | Claude, Duchess of Brittany

( m. 1514) |

| Issue among others... | Francis III, Duke of Brittany Henry II of France Madeleine, Queen of Scots Charles, Duke of Orléans Margaret, Duchess of Savoy |

| House | Valois-Angoulême |

| Father | Charles, Count of Angoulême |

| Mother | Louise of Savoy |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

| Signature |  |

A prodigious patron of the arts, he initiated the French Renaissance by attracting many Italian artists to work for him, including Leonardo da Vinci, who brought the Mona Lisa with him, which Francis had acquired. Francis' reign saw important cultural changes with the rise of absolute monarchy in France, the spread of humanism and Protestantism, and the beginning of French exploration of the New World. Jacques Cartier and others claimed lands in the Americas for France and paved the way for the expansion of the first French colonial empire.

For his role in the development and promotion of a standardized French language, he became known as le Père et Restaurateur des Lettres (the 'Father and Restorer of Letters').[1] He was also known as François du Grand Nez ('Francis of the Large Nose'), the Grand Colas, and the Roi-Chevalier (the 'Knight-King')[1] for his personal involvement in the wars against his great rival Emperor Charles V, who was also King of Spain.

Following the policy of his predecessors, Francis continued the Italian Wars. The succession of Charles V to the Burgundian Netherlands, the throne of Spain, and his subsequent election as Holy Roman Emperor meant that France was geographically encircled by the Habsburg monarchy. In his struggle against Imperial hegemony, he sought the support of Henry VIII of England at the Field of the Cloth of Gold.[2] When this was unsuccessful, he formed a Franco-Ottoman alliance with the Muslim sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, a controversial move for a Christian king at the time.[3]

Early life and accession

Francis of Orléans was born on 12 September 1494 at the Château de Cognac in the town of Cognac,[1] which at that time lay in the province of Saintonge, a part of the Duchy of Aquitaine. Today the town lies in the department of Charente.

Francis was the only son of Charles of Orléans, Count of Angoulême, and Louise of Savoy and a great-great-grandson of King Charles V of France.[4] His family was not expected to inherit the throne, as his third cousin King Charles VIII was still young at the time of his birth, as was his father's cousin the Duke of Orléans, later King Louis XII. However, Charles VIII died childless in 1498 and was succeeded by Louis XII, who himself had no male heir.[5] The Salic Law prevented women from inheriting the throne. Therefore, the four-year-old Francis (who was already Count of Angoulême after the death of his own father two years earlier) became the heir presumptive to the throne of France in 1498 and was vested with the title of Duke of Valois.[5]

In 1505, Louis XII, having fallen ill, ordered that his daughter Claude and Francis be married immediately, but only through an assembly of nobles were the two engaged.[6] Claude was heir presumptive to the Duchy of Brittany through her mother, Anne of Brittany. Following Anne's death, the marriage took place on 18 May 1514.[7] On 1 January 1515, Louis died, and Francis inherited the throne. He was crowned King of France in the Cathedral of Reims on 25 January 1515, with Claude as his queen consort.[8]

Reign

%2C_1515_or_after%2C_NGA_44648.jpg)

As Francis was receiving his education, ideas emerging from the Italian Renaissance were influential in France. Some of his tutors, such as François Desmoulins de Rochefort (his Latin instructor, who later during the reign of Francis was named Grand Aumônier de France) and Christophe de Longueil (a Brabantian humanist), were attracted by these new ways of thinking and attempted to influence Francis. His academic education had been in arithmetic, geography, grammar, history, reading, spelling, and writing and he became proficient in Hebrew, Italian, Latin and Spanish. Francis came to learn chivalry, dancing, and music, and he loved archery, falconry, horseback riding, hunting, jousting, real tennis and wrestling. He ended up reading philosophy and theology and he was fascinated with art, literature, poetry and science. His mother, who had a high admiration for Italian Renaissance art, passed this interest on to her son. Although Francis did not receive a humanist education, he was more influenced by humanism than any previous French king.

Patron of the arts

By the time he ascended the throne in 1515, the Renaissance had arrived in France, and Francis became an enthusiastic patron of the arts. At the time of his accession, the royal palaces of France were ornamented with only a scattering of great paintings, and not a single sculpture, either ancient or modern. During Francis' reign, the magnificent art collection of the French kings, which can still be seen at the Louvre Palace, was begun.

Francis patronized many great artists of his time, including Andrea del Sarto and Leonardo da Vinci; the latter of whom was persuaded to make France his home during his last years. While da Vinci painted very little during his years in France, he brought with him many of his greatest works, including the Mona Lisa (known in France as La Joconde), and these remained in France after his death. Other major artists to receive Francis' patronage included the goldsmith Benvenuto Cellini and the painters Rosso Fiorentino, Giulio Romano, and Primaticcio, all of whom were employed in decorating Francis' various palaces. He also invited the noted architect Sebastiano Serlio (1475–1554), who enjoyed a fruitful late career in France.[9] Francis also commissioned a number of agents in Italy to procure notable works of art and ship them to France.

Man of letters

Francis was also renowned as a man of letters. When Francis comes up in a conversation among characters in Baldassare Castiglione's Book of the Courtier, it is as the great hope to bring culture to the war-obsessed French nation. Not only did Francis support a number of major writers of the period, he was a poet himself, if not one of particular abilities. Francis worked diligently at improving the royal library. He appointed the great French humanist Guillaume Budé as chief librarian and began to expand the collection. Francis employed agents in Italy to look for rare books and manuscripts, just as he had agents looking for art works. During his reign, the size of the library greatly increased. Not only did he expand the library, there is also evidence that he read the books he bought for it, a much rarer event in the royal annals. Francis set an important precedent by opening his library to scholars from around the world in order to facilitate the diffusion of knowledge.

In 1537, Francis signed the Ordonnance de Montpellier, which decreed that his library be given a copy of every book to be sold in France. Francis' older sister, Marguerite, Queen of Navarre, was also an accomplished writer who produced the classic collection of short stories known as the Heptameron. Francis corresponded with the abbess and philosopher Claude de Bectoz, of whose letters he was so fond that he would carry them around and show them to the ladies of his court.[10] Together with his sister, he visited her in Tarascon.[11]

Construction

Francis poured vast amounts of money into new structures. He continued the work of his predecessors on the Château d'Amboise and also started renovations on the Château de Blois. Early in his reign, he began construction of the magnificent Château de Chambord, inspired by the architectural styles of the Italian renaissance, and perhaps even designed by Leonardo da Vinci. Francis rebuilt the Château du Louvre, transforming it from a medieval fortress into a building of Renaissance splendour. He financed the building of a new City Hall (the Hôtel de Ville) for Paris in order to have control over the building's design. He constructed the Château de Madrid in the Bois de Boulogne and rebuilt the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye. The largest of Francis' building projects was the reconstruction and expansion of the Château de Fontainebleau, which quickly became his favourite place of residence, as well as the residence of his official mistress, Anne, Duchess of Étampes. Each of Francis' projects was luxuriously decorated both inside and out. Fontainebleau, for instance, had a gushing fountain in its courtyard where quantities of wine were mixed with the water.

Military action

Although the Italian Wars (1494–1559) came to dominate the reign of Francis I, the wars were not the sole focus of his policies. Francis merely continued the incessant wars that his predecessors had started and that his successors on the throne of France would drag on after Francis' death. Indeed, the Italian Wars had begun when Milan sent a plea to King Charles VIII of France for protection against the aggressive actions of the King of Naples.[12] Militarily and diplomatically, Francis' reign was a mixed bag of success and failure. Francis tried and failed to become Holy Roman Emperor at the Imperial election of 1519. However, there were also temporary victories, such as in the portion of the Italian Wars called the War of the League of Cambrai (1508–1516) and, more specifically, to the final stage of that war, which history refers to simply as "Francis' First Italian War" (1515–1516), when Francis routed the combined forces of the Papal States and the Old Swiss Confederacy at Marignano on 13–15 September 1515. This victory at Marignano allowed Francis to capture the Italian city-state of Milan. Later, in November 1521, during the Four Years' War (1521–1526) and facing the advancing Imperial forces of the Holy Roman Empire and open revolt within Milan, Francis was forced to abandon Milan, thus, cancelling the triumph at Marignano.

Much of the military activity of Francis's reign was focused on his sworn enemy, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. Francis and Charles maintained an intense personal rivalry. Charles, in fact, brashly challenged Francis to single combat multiple times. In addition to the Holy Roman Empire, Charles personally ruled Spain, Austria, and a number of smaller possessions neighboring France. He was thus a constant threat to Francis' kingdom.

Francis attempted to arrange an alliance with Henry VIII of England at the famous meeting at the Field of Cloth of Gold on 7 June 1520, but despite a lavish fortnight of diplomacy they failed to reach an agreement.[13]

Francis suffered his most devastating defeat at the Battle of Pavia on 24 February 1525, during part of the continuing Italian Wars known as the Four Years' War. Francis was actually captured by the forces of Charles V after Cesare Hercolani was able to injure his horse, leading Francis to be captured by Diego Dávila, Alonso Pita da Veiga and Juan de Urbieta, from Guipúzcoa. For this reason, Hercolani was named "Victor of the battle of Pavia". Zuppa alla Pavese was supposedly invented on the spot to feed the captive king right after the battle.[14] There are allegations that Francis would have been killed by mistake by one of Charles' soldiers had Pedro de Valdivia —the future conqueror of Chile— not intervened.[15]

Francis I was held captive in Madrid. In a letter to his mother he wrote, "Of all things, nothing remains to me but honour and life, which is safe." This line has come down in history famously as "All is lost save honour."[16] In the Treaty of Madrid, signed on 14 January 1526, Francis was forced to make major concessions to Charles V before he was freed on 17 March 1526. An ultimatum from Ottoman Sultan Suleiman to Charles V also played an important role in his release. Among the concessions that Francis I yielded to Charles V were the surrender of any claims to Naples and Milan in Italy.[17] Francis I was also forced to recognise the independence of the duchy of Burgundy, which had become part of France since the death of Charles, Duke of Burgundy on 5 January 1477,[18] during the reign of Louis XI.

Furthermore, France was required to give up all claims to Flanders and the Artois.[17] Additionally, Francis I was allowed to return to France in exchange for his two sons, Francis and Henry, but once he was free he argued that his agreement with Charles was made under duress. He also claimed that the agreement was void because his sons were taken hostage with the implication that his word alone could not be trusted. Thus he firmly repudiated it.

Francis persevered in his hatred of Charles V and desire to control Italy by conquest. The repudiation of the Treaty of Madrid led to the War of the League of Cognac of 1526–30. By the mid-1520s, Pope Clement VII wished to liberate Italy from foreign domination, especially that of Charles V, so to that end he negotiated with Venice to form the League of Cognac. Francis I willingly joined this anti-Imperial league on 22 May 1526.[19]

After the league failed, Francis concluded a secret alliance with the Landgrave of Hesse on 27 January 1534. This was directed against Charles V on the pretext of assisting the Duke of Wurttemberg to regain his traditional seat, from which Charles had removed him in 1519. Francis also obtained the help of the Ottoman Empire and renewed the contest in Italy in the Italian War of 1536–1538 after the death of Francesco II Sforza, the ruler of Milan. This round of fighting, which had little result, was ended by the Truce of Nice. The agreement collapsed, however, which led to Francis' final attempt on Italy in the Italian War of 1542–1546. This time Francis managed to hold off the forces of Charles V and England's Henry VIII. Charles V was forced to sign the Treaty of Crépy because of his financial difficulties and conflicts with the Schmalkaldic League.

Relations with the New World and Asia

Francis had been much aggrieved at the papal bull Aeterni regis: in June 1481 Portuguese rule over Africa and the Indies was confirmed by Pope Sixtus IV. Thirteen years later, on 7 June 1494, Portugal and the Crown of Castille signed the Treaty of Tordesillas under which the newly discovered lands would be divided between the two signatories. All this prompted King Francis to declare, "The sun shines for me as it does for others. I would very much like to see the clause of Adam’s will by which I should be denied my share of the world."[20]

In order to counterbalance the power of the Habsburg Empire under Charles V, especially its control of large parts of the New World through the Crown of Spain, Francis I endeavoured to develop contacts with the New World and Asia. Fleets were sent to the Americas and the Far East, and close contacts were developed with the Ottoman Empire permitting the development of French Mediterranean trade as well as the establishment of a strategic military alliance.

The port city now known as Le Havre was founded in 1517 during the early years of Francis' reign. The construction of a new port was urgently needed in order to replace the ancient harbours of Honfleur and Harfleur, whose utility had decreased due to silting. Le Havre was originally named Franciscopolis after the King who founded it, but this name did not survive into later reigns.

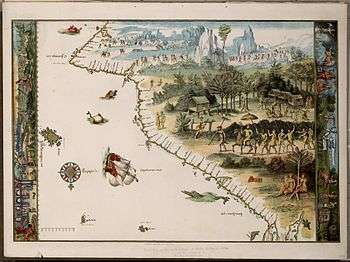

Americas

In 1524, Francis assisted the citizens of Lyon in financing the expedition of Giovanni da Verrazzano to North America. On this expedition, Verrazzano visited the present site of New York City, naming it New Angoulême, and claimed Newfoundland for the French crown. Verrazzano's letter to Francis of 8 July 1524 is known as the Cèllere Codex.[21]

In 1531, Bertrand d'Ornesan tried to establish a French trading post at Pernambuco, Brazil.[22]

In 1534, Francis sent Jacques Cartier to explore the St. Lawrence River in Quebec to find "certain islands and lands where it is said there must be great quantities of gold and other riches".[23] In 1541, Francis sent Jean-François de Roberval to settle Canada and to provide for the spread of "the Holy Catholic faith."

Far East Asia

French trade with East Asia was initiated during the reign of Francis I with the help of shipowner Jean Ango. In July 1527, a French Norman trading ship from the city of Rouen is recorded by the Portuguese João de Barros as having arrived in the Indian city of Diu.[24] In 1529, Jean Parmentier, on board the Sacre and the Pensée, reached Sumatra.[24][25] Upon its return, the expedition triggered the development of the Dieppe maps, influencing the work of Dieppe cartographers such as Jean Rotz.[26]

Ottoman Empire

Under the reign of Francis I, France became the first country in Europe to establish formal relations with the Ottoman Empire and to set up instruction in the Arabic language under the guidance of Guillaume Postel at the Collège de France.[27]

In a watershed moment in European diplomacy, Francis came to an understanding with the Ottoman Empire that developed into a Franco-Ottoman alliance. The alliance has been called "the first nonideological diplomatic alliance of its kind between a Christian and non-Christian empire".[28] It did, however, cause quite a scandal in the Christian world[29] and was designated "the impious alliance", or "the sacrilegious union of the [French] Lily and the [Ottoman] Crescent." Nevertheless, it endured for many years, since it served the objective interests of both parties.[30] The two powers colluded against Charles V, and in 1543 they even combined for a joint naval assault in the Siege of Nice.

In 1533, Francis I sent colonel Pierre de Piton as ambassador to Morocco, initiating official France-Morocco relations.[31] In a letter to Francis I dated 13 August 1533, the Wattassid ruler of Fez, Ahmed ben Mohammed, welcomed French overtures and granted freedom of shipping and protection of French traders.

Bureaucratic reform and language policy

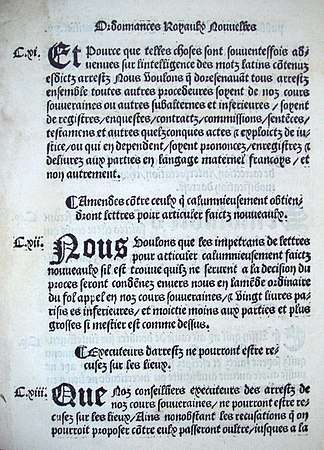

Francis took several steps to eradicate the monopoly of Latin as the language of knowledge. In 1530, he declared French the national language of the kingdom, and that same year opened the Collège des trois langues, or Collège Royal, following the recommendation of humanist Guillaume Budé. Students at the Collège could study Greek, Hebrew and Aramaic, then Arabic under Guillaume Postel beginning in 1539.[32]

In 1539, in his castle in Villers-Cotterêts,[33] Francis signed the important edict known as Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts, which, among other reforms, made French the administrative language of the kingdom as a replacement for Latin. This same edict required priests to register births, marriages, and deaths, and to establish a registry office in every parish. This initiated the first records of vital statistics with filiations available in Europe.

Religious policies

Divisions in Christianity in Western Europe during Francis' reign created lasting international rifts. Martin Luther's preaching and writing sparked the Protestant Reformation, which spread through much of Europe, including France.

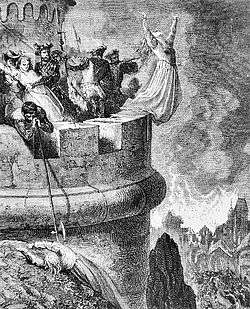

Initially, Francis was relatively tolerant of the new movement, under the influence of his beloved sister Marguerite de Navarre, who was genuinely attracted by Luther's theology. He even considered it politically useful, as it caused many German princes to turn against his enemy Charles V. In 1533 Francis even dared to suggest to Pope Clement VII that he convene a church council in which Catholic and Protestant rulers would have an equal vote in order to settle their differences – an offer rejected by both the Pope and Charles V. Beginning in 1523, however, Francis burned several heretics at the Place Maubert.[34]

Francis' attitude towards Protestantism changed for the worse following the "Affair of the Placards", on the night of 17 October 1534, in which notices appeared on the streets of Paris and other major cities denouncing the Catholic mass. The most fervent Catholics were outraged by the notice's allegations. Francis himself came to view the movement as a plot against him and began to persecute its followers. Protestants were jailed and executed. In some areas whole villages were destroyed. In Paris, after 1540, Francis had heretics such as Etienne Dolet tortured and burned.[35] Printing was censored and leading Protestant reformers such as John Calvin were forced into exile. The persecutions soon numbered thousands of dead and tens of thousands of homeless.[36]

Persecutions against Protestants were codified in the Edict of Fontainebleau (1540) issued by Francis. Major acts of violence continued, as when Francis ordered the execution of one of the historical pre-Lutheran groups, the Waldensians, at the Massacre of Mérindol in 1545.

Death

Francis died at the Château de Rambouillet on 31 March 1547, on his son and successor's 28th birthday. It is said that "he died complaining about the weight of a crown that he had first perceived as a gift from God".[37] He was interred with his first wife, Claude, Duchess of Brittany, in Saint Denis Basilica. He was succeeded by his son, Henry II.

Francis' tomb and that of his wife and mother, along with the tombs of other French kings and members of the royal family, were desecrated on 20 October 1793 during the Reign of Terror at the height of the French Revolution.

Image

Francis' personal emblem was the salamander and his Latin motto was Nutrisco et extinguo ("I nourish [the good] and extinguish [the bad]").

His long nose earned him the nickname François du Grand Nez ("Francis of the Big Nose"), he was also colloquially known as the "Grand Colas" or "Bonhomme Colas". For his personal involvement in battles, he was known as le Roi-Chevalier ("the Knight-King") or the le Roi-Guerrier ("the Warrior-King").[38]

Marriage and issue

On 18 May 1514, Francis married his second cousin Claude, the daughter of King Louis XII of France and Duchess Anne of Brittany. The couple had seven children:

- Louise (19 August 1515 – 21 September 1517): died young; engaged to Charles I of Spain almost from birth until death.

- Charlotte (23 October 1516 – 8 September 1524): died young; engaged to Charles I of Spain from 1518 until death.

- Francis (28 February 1518 – 10 August 1536), who succeeded his mother Claude as Duke of Brittany, but died aged 18, unmarried and childless.

- Henry II (31 March 1519 – 10 July 1559). Succeeded Francis I as King of France. Married Catherine de' Medici, had issue.

- Madeleine (10 August 1520 – 2 July 1537), who married James V of Scotland and had no issue.

- Charles (22 January 1522 – 9 September 1545), who died unmarried and childless.

- Margaret (5 June 1523 – 14 September 1574), who married Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy, in 1559 and had issue.

On 7 July 1530, Francis I married his second wife Eleanor of Austria,[39] a sister of the Emperor Charles V. The couple had no children. During his reign, Francis kept two official mistresses at court. The first was Françoise de Foix, Countess of Châteaubriant. In 1526, she was replaced by the blonde-haired, cultured Anne de Pisseleu d'Heilly, Duchess of Étampes who, with the death of Queen Claude two years earlier, wielded far more political power at court than her predecessor had done. Another of his earlier mistresses was allegedly Mary Boleyn, mistress of King Henry VIII and sister of Henry's future wife, Anne Boleyn.[40]

Francis I in films, stage and literature

The amorous exploits of Francis inspired the 1832 play by Fanny Kemble, Francis the First, and the 1832 play by Victor Hugo, Le Roi s'amuse ("The King's Amusement"), which featured the jester Triboulet, the inspiration for the 1851 opera Rigoletto by Giuseppe Verdi.

Francis was first played in a George Méliès movie by an unknown actor in 1907, and has also been played by Claude Garry (1910), Aimé Simon-Girard (1937), Sacha Guitry (1937), Gérard Oury (1953), Jean Marais (1955), Pedro Armendáriz (1956), Claude Titre (1962), Bernard Pierre Donnadieu (1990). Timothy West (1998) and Emmanuel Leconte (2007– 2010).

Francis was portrayed by Peter Gilmore in the comedy film Carry On Henry charting the fictitious two extra wives of Henry VIII (including Marie cousin of King Francis).

Francis receives a mention in a minor story in Laurence Sterne's novel Tristram Shandy. The narrator claims that the king, wishing to win the favour of Switzerland, offers to make the country the godmother of his son. When, however, their choice of name conflicts, he declares war.

He is also mentioned in Jean de la Brète's novel Reine – Mon oncle et mon curé, where the main character Reine de Lavalle idolises him after reading his biography, much to the dismay of the local priest.

He often receives mentions in novels on the lives of either of the Boleyn sisters – Mary Boleyn (d. 1543) and her sister, Queen Anne Boleyn (executed 1536), both of whom were for a time educated at his court. Mary had, according to several accounts, been Francis' one-time mistress and Anne had been a favourite of his sister: the novels The Lady in the Tower, The Other Boleyn Girl, The Last Boleyn, Dear Heart, How Like You This? and Mademoiselle Boleyn feature Francis in their story. He appears in Hilary Mantel's Wolf Hall about Henry VIII's minister Thomas Cromwell and is often referred to in its sequel, Bring Up the Bodies.

Francis is portrayed in Diane Haeger's novel Courtesan about Diane de Poitiers and Henri II.

Francis appears as the patron of Benvenuto Cellini in the 1843 French novel L'Orfèvre du roi, ou Ascanio by Alexandre Dumas, père.

Samuel Shellabarger's novel The King's Cavalier describes Francis the man, and the cultural and political circumstances of his reign, in some detail.

He was a recurring character in the Showtime series The Tudors, opposite Jonathan Rhys Meyers as Henry VIII and Natalie Dormer as Anne Boleyn. Francis is played by French actor, Emmanuel Leconte.

He and his court set the scene for Friedrich Schiller's ballad Der Handschuh (The Glove).

Francis I (played by Timothy West) and Francis's son Henry II (played by Dougray Scott) are central figures in the 1998 movie Ever After, a retelling of the Cinderella story. The plot includes Leonardo da Vinci (played by Patrick Godfrey) arriving at Francis's court with the Mona Lisa.

He is played by Alfonso Bassave in the TVE series Carlos, rey emperador, opposite Álvaro Cervantes as Charles V.

Ancestors

| Ancestors of Francis I of France | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- Knecht, R.J. Francis I, (Cambridge University Press, 1984), 1–2.

- Knecht, R.J. Francis I, 77–78.

- Knecht, R.J. Francis I, 224–225, 230.

- Knecht, Robert. The Valois, (Hambledon Continuum, 2004), 112.

- Knecht, R.J. Francis I, 3.

- Knecht, R.J. Francis I, 8–9.

- Knecht, R.J. Francis I, 11.

- Knecht, R.J. Francis I, 16.

- Serlio, Sebastiano (1996). On Architecture. Hart & Hicks (ed) Volume 2. Yale. pp. xi.

- Plats, John (1826). A New Universal Biography: Forming the first volume of series III. Sherwood, Gilbert and Piper. p. 301.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Cholakian, Patricia Francis; Cholakian, Rouben Charles (2006). Marguerite de Navarre: mother of the Renaissance. Columbia University Press. p. 49. ISBN 0231134126.

- Hoyt, Robert S. & Stanley Chodorow, Europe in the Middle Ages (Harcourt, Brace & Jovanovich Inc.: New York, 1976) p. 619.

- Glenn, Richardson (2014). The Field of Cloth of Gold. Yale University Press. pp. 32–36. ISBN 9780300160390. OCLC 862814775.

- Andrews, Colman. Country Cooking of Italy. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2012, p. 60. ISBN 9781452123929.

- Córdoba, J. (2014). "Inés Suárez y la conquista de Chile". Iberoamérica Social: Revista-red de Estudios Sociales (in Spanish). III: 38–42.

- Isaac, Jules (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 935.

- Mallet, Michael and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559 (Harlow, England: Pearson Education Limited, 2012) p. 153.

- Kendall, Paul Murray. Louis XI: The Universal Spider (New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1971) p. 314.

- Mallett, Michael and Christine Shaw, The Italian Wars: 1494–1559, p. 155.

- Lacoursière, Jacques (2005). Canada Quebec 1534–2000. Québec: Septentrion. p. 28. ISBN 978-2894481868.

-

- Destombes, M. (1954). "Nautical Charts Attributed to Verrazano (1525–1528)". Imago Mundi. 11: 57–66. doi:10.1080/03085695408592059. OCLC 1752690.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Knecht, R.J. Francis I, (Cambridge University Press, 1982), 375.

- Knecht, R.J. Francis I, 333.

- The English history of the British Empire p. 61. 1940. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- Oaten, Edward Farley (1991). European travellers in India p. 123. ISBN 9788120607101. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- Quinn, David B. (1 January 1990). Explorers and colonies: America, 1500–1625, p. 57. ISBN 9781852850241. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- Eastern wisdom and learning: the study of Arabic in seventeenth-century ... by G. J. Toomer p.26-7

- Kann, Robert A. (26 November 1980). Kann, p. 62. ISBN 9780520042063. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- Miller, p. 2

- Merriman, Roger Bigelow (March 2007). Merriman, p. 133. ISBN 9781406772722. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- "Francois I, hoping that Morocco would open up to France as easily as Mexico had to Spain, sent a commission, half commercial and half diplomatic, which he confided to one Pierre de Piton. The story of his mission is not without interest" in The conquest of Morocco by Cecil Vivian Usborne, S. Paul & co. ltd., 1936, p. 33.

- McCabe, Ina Baghdianitz. Orientalism in early modern France. ISBN 978-1-84520-374-0, p. 25 ff.

- Knecht, Robert J. (21 January 2002). The rise and fall of Renaissance France, 1483–1610, p. 158. ISBN 9780631227298. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- Pierre Goubert, The Course of French History Psychology Press, 1991, p. 92.

- Goubert, op. cit., p.92

- R. J. Knecht, Francis I' pp.405–406

- Cavendish, Richard. "The Marriage of Mary, Queen of Scots | History Today". www.historytoday.com.

- Larousse

- Wurzbach, Constantin von (1860). "Habsburg, Eleonore von Oesterreich (Tochter Philipp's von Oesterreich)". Biographisches Lexikon des Kaiserthums Oesterreich. Vienna: Verlag L. C. Zamarski.

- Letters and Papers of the Reign of Henry VIII, X, no.450

- Anselme de Sainte-Marie, Père (1726). Histoire généalogique et chronologique de la maison royale de France [Genealogical and chronological history of the royal house of France] (in French). 1 (3rd ed.). Paris: La compagnie des libraires. p. 110.

- Adams, Tracy (2010). The Life and Afterlife of Isabeau of Bavaria. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 255.

- Azzolini, Monica (2013). The Duke and the Stars: Astrology and Politics in Renaissance Milan. Harvard University Press. p. 120.

- Y. Gicquel, Alain IX de Rohan, p. 97

- Gicquel, Yvonig (1986). Alain IX de Rohan, 1382–1462: un grand seigneur de l'âge d'or de la Bretagne (in French). Éditions Jean Picollec. p. 480. ISBN 9782864770718.

- Jones, Michael (1988). The Creation of Brittany. London: Hambledon Press. p. 123. ISBN 090762880X.

- Palluel-Guillard, André. "La Maison de Savoie" (in French). Conseil Savoie Mont Blanc. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- Jackson-Laufer, Guida Myrl (1999). Women Rulers Throughout the Ages: An Illustrated Guide. ABC-CLIO. p. 231.

- Hill, George (2010). "Janus (1398–1432)". A History of Cyprus. Cambridge University Press. p. 468. ISBN 9781108020633.

- Anselme, vol. 3, p. 137

- Leguai, André (2005). "Agnès de Bourgogne, duchesse de Bourbon (1405?–1476)". Les ducs de Bourbon, le Bourbonnais et le royaume de France à la fin du Moyen Age [The dukes of Bourbon, the Bourbonnais and the kingdom of France at the end of the Middle Ages] (in French). Yzeure: Société bourbonnaise des études locales. pp. 145–160.

- O'Reilly, Elizabeth Boyle (1921). How France Built Her Cathedrals: A Study in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries. Harper & Brothers. p. 265.

- van Leeuwen-Canneman, Mieke (13 January 2014). "Margaretha van Beieren (1363–1424)" [Margaret of Bavaria]. Online Dictionary of Dutch Women. Digitaal Vrouwenlexicon van Nederland. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

Further reading

- Clough, C.H., "Francis I and the Courtiers of Castiglione’s Courtier." European Studies Review. vol viii, 1978.

- Denieul-Cormier, Anne. The Renaissance in France. trans. Anne Fremantle and Christopher Fremantle. London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd., 1969.

- Grant, A.J. The French Monarchy, Volume I. New York: Howard Fertig, 1970.

- Guy, John. Tudor England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988.

- Jensen, De Lamar. Renaissance Europe. Lexington: D.C. Heath and Company, 1992.

- Knecht, R.J. Renaissance Warrior and Patron: The Reign of Francis I. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Major, J. Russell. From Renaissance Monarchy to Absolute Monarchy. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994.

- Potter, D. L. Renaissance France at War – Armies, Culture and Society, c.1480–1560. Boydell Press., 2008

- Seward, Desmond. François I: Prince of the Renaissance. New York: MacMillan Publishing Co., 1973.

External links

Francis I of France Cadet branch of the Capetian dynasty Born: 12 September 1494 Died: 31 March 1547 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Louis XII |

King of France 1 January 1515 – 31 March 1547 |

Succeeded by Henry II |

| Preceded by Claude as sole duchess |

Duke of Brittany 18 May 1514 – 1 January 1515 with Claude |

Succeeded by Claude as sole duchess |

| Preceded by Maximilian Sforza |

Duke of Milan 1515–1521 |

Succeeded by Francis II Sforza |

| Preceded by Francis II Sforza |

Duke of Milan 1524–1525 | |

| French nobility | ||

| Vacant Merged in the crown Title last held by Louis |

Duke of Valois 1498 – 1 January 1515 |

Vacant Merged in the crown Title next held by Margaret |

| Preceded by Charles |

Count of Angoulême 1 January 1496 – 1 January 1515 |

Vacant Merged in the crown Title next held by Louise |