Tupinambá people

The Tupinambá are one of the various Tupi ethnic groups that inhabit present-day Brazil since before the conquest of the region by Portuguese colonial settlers. In the first years of contact with the Portuguese, the Tupinambás lived in the whole Eastern coast of Brazil, and the name was also applied to other Tupi-speaking groups such as the Tupiniquim, Potiguara, Tupinambá, Temiminó, Caeté, Tabajara, Tamoio, Tupinaé among others[1]. In an exclusive sense, it can be applied to the Tupinambá peoples who once inhabited the right shore of the São Francisco river in the Recôncavo Baiano and from the Cabo de São Tomé in Rio de Janeiro to the town of São Sebastião in São Paulo[2]. Their language survives today in the form of Nheengatu.

There are two remaining regions inhabited by the Tupinambá. The Tupinambá of Olivença live in the Atlantic Forest region of southern Bahia. Its area is 10 kilometers north of the city of Ilhéus and extends from the sea coast of the village of Olivença to the Serra das Trempes and Serra do Padeiro[3]. The other group lives in the low Tapajós in the Brazilian state of Pará[4].

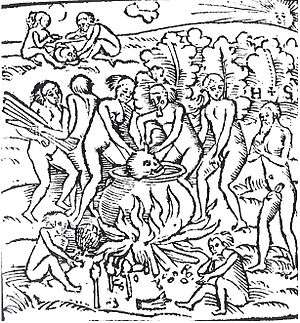

The Tupinambás were abundantly described in André Thevet's 1572 Cosmographie universelle (English: The New Found World, or Antarctike), in Jean de Léry's Histoire d'un voyage faict en la terre du Brésil (English: History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil) (1578), and Hans Staden's Warhaftige Historia und beschreibung eyner Landtschafft der Wilden Nacketen (English: True History: An Account of Cannibal Captivity in Brazil), in which he describes the Tupinamba practicing cannibalism. Thevet and Léry were an inspiration for Montaigne's famous essay Of Cannibals,[5][6] and influenced the creation of the myth of the "noble savage" during the Enlightenment.

Gallery

A Tupinambá named "Louis Henri" who visited Louis XIII in Paris in 1613, in Claude d'Abbeville, Histoire de la mission.

A Tupinambá named "Louis Henri" who visited Louis XIII in Paris in 1613, in Claude d'Abbeville, Histoire de la mission.- Catarina Paraguaçu, wife of Portuguese sailor Diogo Álvares Correia, in an 1871 painting.

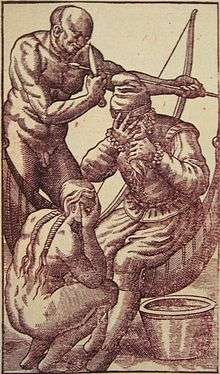

"Salutations larmoyantes" ("Tearful salutations") describing the Tupinambás, in Histoire d'un voyage faict en la terre du Brésil (1578), Jean de Léry, 1580 edition.

"Salutations larmoyantes" ("Tearful salutations") describing the Tupinambás, in Histoire d'un voyage faict en la terre du Brésil (1578), Jean de Léry, 1580 edition.

The Tupinambá may have given their name to the common French word for the Jerusalem Artichoke, the topinambour.[8]

References

- Navarro, Eduardo de Almeida (1998). Método moderno de tupi antigo : a língua do Brasil dos primeiros séculos. Petrópolis: Editora Vozes. ISBN 85-326-1953-3. OCLC 40480983.

- Bueno, Eduardo. (2001). Capitães do Brasil : a saga dos primeiros colonizadores (1a ed.). Cascais, Portugal: Pergaminho. ISBN 972-711-401-6. OCLC 266073039.

- "Tupinambá de Olivença - Povos Indígenas no Brasil". pib.socioambiental.org. Retrieved 2019-12-31.

- "A autodemarcação da Terra Indígena Tupinambá no Baixo Tapajós | Combate Racismo Ambiental". racismoambiental.net.br. Retrieved 2019-12-31.

- Michel de Montaigne,Essais, Book 1, Chap.30

- Carlo Ginzburg (2012)Threads and Traces: True, False, Fictive, (papers), University of California Press, ISBN 9780520274488, Chapter 3: Montaigne, Cannibals, and Grottoes

- "True History and Description of a Country in America, whose Inhabitants are Savage, Naked, Very Godless and Cruel Man-Eaters". World Digital Library. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- Graham, Peter. "Chez Gram". Retrieved 17 February 2018.

Sources

- Léry, Jean, and Janet Whatley. History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil, Otherwise Called America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990. Print.