Fort Duquesne

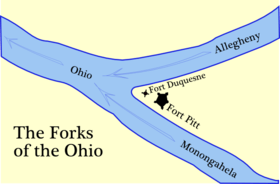

Fort Duquesne (/duːˈkeɪn/, French: [dykɛn]; originally called Fort Du Quesne) was a fort established by the French in 1754, at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers. It was later taken over by the English, and later Americans, and developed as Pittsburgh in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. Fort Duquesne was destroyed by the French, prior to English conquest during the Seven Years' War, known as the French and Indian War on the North American front. The latter replaced it, building Fort Pitt between 1759 and 1761. The site of both forts is now occupied by Point State Park, where the outlines of the two forts have been laid in brick.

| Fort Duquesne | |

|---|---|

| Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania | |

| |

| Type | Fort |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1754 |

| In use | 1754–1758 |

| Battles/wars | French and Indian War |

| Designated | May 8, 1959[1] |

Background

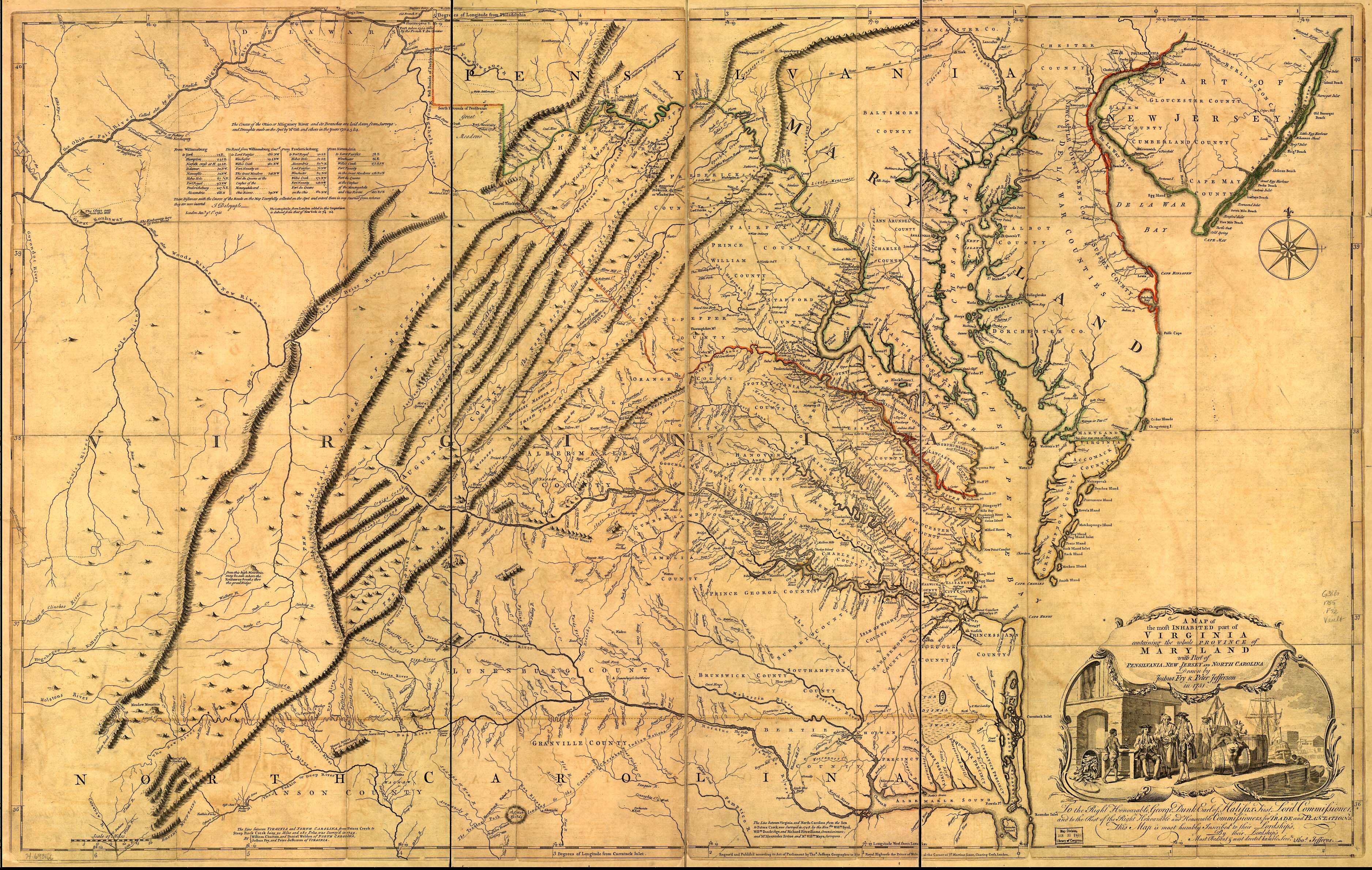

Fort Duquesne, built at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers which forms the Ohio River, was considered strategically important for controlling the Ohio Country,[2] both for settlement and for trade. The English merchant William Trent had established a highly successful trading post at the forks as early as the 1740s, to do business with a number of nearby Native American villages. Both the French and the British were keen to gain advantage in the area.

As the area was within the drainage basin of the Mississippi River, the French had claimed it as theirs. They controlled New France (Quebec), the Illinois Country along the Mississippi, and La Louisiane (the ports of New Orleans and Mobile, Alabama, and environs).

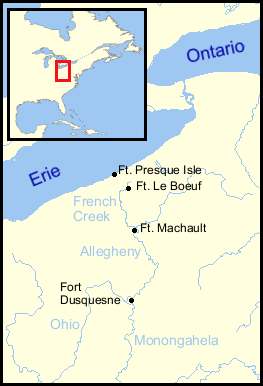

In the early 1750s, the French began construction of a line of forts, starting with Fort Presque Isle on Lake Erie in present-day Erie, Pennsylvania, followed by Fort Le Boeuf, about 15 miles south in present-day Waterford, Pennsylvania, and Fort Machault, on the Allegheny River in Venango County in present-day Franklin, Pennsylvania.

Robert Dinwiddie, Lieutenant Governor of the Virginia Colony, thought these forts threatened extensive claims to the land area by Virginians (including himself) of the Ohio Company. In late autumn 1753, Dinwiddie dispatched a young Virginia militia officer named George Washington to the area to deliver a letter to the French commander at Fort Le Boeuf, asking them to leave. Washington was also to assess French strength and intentions. After reaching Fort Le Boeuf in December, Washington was politely rebuffed by the French [3]

Fort's construction and replacement

Following Washington's return to Virginia in January 1754, Dinwiddie sent Virginians to build Fort Prince George at the Forks of the Ohio. Work began on the fort on February 17. By April 18, a much larger French force of five hundred under the command of Claude-Pierre Pécaudy de Contrecœur arrived at the forks, forcing the small British garrison to surrender. The French knocked down the tiny British fort and built Fort Duquesne, named in honor of Marquis Duquesne, the governor-general of New France. The fort was built on the same model as the French Fort Frontenac on Lake Ontario.[4]

Meanwhile, Washington, newly promoted to Colonel of the newly created Virginia Regiment, set out on 2 April 1754 with a small force to build a road to, and then defend, Fort Prince George. Washington was at Wills Creek in north central Maryland when he received news of the fort's surrender. On May 25, Washington assumed command of the expedition upon the death of Colonel Joshua Fry. Two days later, Washington encountered a Canadian scouting party near a place now known as Jumonville Glen (several miles east of present-day Uniontown). Washington attacked the French Canadians, killing 10 in the early morning hours, and took 21 prisoners, of whom many were ritually killed by the Native American allies of the British.

The Battle of Jumonville Glen is widely considered the formal start of the French and Indian War, the North American front of the Seven Years' War.[5][6]

Washington ordered construction of Fort Necessity at a large clearing known as the Great Meadows. On 3 July 1754, the counterattacking French and Canadians forced Washington to surrender Fort Necessity. After disarming them, they released Washington and his men to return home.

Although Fort Duquesne's location at the forks looked strong on a map—controlling the confluence of three rivers—the reality was rather different. The site was low, swampy, and prone to flooding. In addition, the position was dominated by highlands across the Monongahela River, which would allow an enemy to bombard the fort with ease. Pécaudy de Contrecœur was preparing to abandon the fort in the face of Braddock's advance in 1755. He was able to retain it due to the advancing British force being annihilated (see below). When the Forbes expedition approached in 1758, the French had initial success in the Battle of Fort Duquesne against the English vanguard, but were forced to abandon the fort in the face of the much superior size of Forbes' main force.

The French held the fort successfully early in the war, turning back the expedition led by General Edward Braddock during the 1755 Battle of the Monongahela. George Washington served as one of General Braddock's aides. A smaller attack by James Grant in September 1758 was repulsed with heavy losses. Two months later, on November 25, the Forbes Expedition under General John Forbes took possession Fort Duquesne after the French destroyed and abandoned the site.[7]

Present-day site

Fort Duquesne was built at the point of land of the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers, where they form the Ohio River. Since the late 20th century, this area of downtown Pittsburgh has been preserved as Point State Park, or simply, "the Point." The park includes a brick outline of the fort's walls, as well as outlines to mark the later Fort Pitt.

In May 2007, Thomas Kutys, an archaeologist with A.D. Marble & Company, a Cultural Resource Management firm based in Conshohocken, Pennsylvania, discovered a stone and brick drain on the Fort Duquesne site. It is thought to have drained one of the fort's many buildings. Due to its depth in the ground, this drain may be all of the fort that has survived. The entire northern half of the former fort site was disrupted and destroyed by the heavy industrial development of the area in the 19th century.[8]

Commemoration

1958 issue

On November 25, 1958, the 200th anniversary of the capture of Fort Duquesne, the U.S. Post Office issued a 4-cent Fort Duquesne bicentennial commemorative stamp. It was first released for sale at the post office in Pittsburgh. The design was reproduced from a composite drawing, using various figures taken from an etching by T.B. Smith and a painting portraying the British occupation of the site as the Fort Duquesne blockhouse burns in the background.

Colonel Washington is depicted on horseback in the center, while General Forbes, who was debilitated by intestinal disease, is shown lying on a stretcher. The stamp also depicts Colonel Henry Bouquet, who was second in command to the ailing Forbes, and other figures who represent the Virginia militia and provincial army.[9]

In media

Old Fort Duquesne, or, Captain Jack, the Scout, is an historical novel by Charles McKnight, a retelling of the events of Fort Duquesne during the French and Indian War.

Fort Duquesne appears in episode seven of the first season of the TV series Timeless.

Fort Duquesne also appears in the video game Assassin's Creed III, although it looks nothing like its real-life counterpart, and is referred to as Fort Duquesne long after the British rebuilt it. It is one of the main forts in the game that Connor has to conquer and reclaim for the Continental Army.

See also

Further reading

- Fort Duquesne and Fort Pitt: Early Names of Pittsburgh Streets. Daughters of the American Revolution. Pittsburgh Chapter (Pittsburgh, Pa.). 1907. p. 47. E'book

- Craig, Neville B. (1876). The Olden Time: A Monthly Publication Devoted to the Preservation of Documents and Other Authentic Information in Relation to the Early Explorations and the Settlement and Improvement of the Country Around the Head of the Ohio, Volume 1. R. Clarke & Company, 583 pages;.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link), E'book

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fort Duquesne. |

- "PHMC Historical Markers Search" (Searchable database). Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 2014-01-25.

- "The Diaries of George Washington, Vol. 1", Donald Jackson, ed., Dorothy Twohig, assoc. ed. Library of Congress American Memory site

- Bulldogs.

- France in America, Fitzhenry & Whiteside Limited, p. 181

- Anderson, Fred (2000). Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766. New York: Knopf. p. 747. ISBN 0-375-40642-5.

- Miller, John J.; Molesky, Mark (18 December 2007). Our Oldest Enemy: A History of America's Disastrous Relationship with France. Random House. pp. 23–4. ISBN 9780307419187.

- Withers, & Draper, 1895, p. 73

- Archived September 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "Fort Duquesne Issue". Smithsonian National Postal Museum. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Fred. Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754–1766. New York: Knopf, 2000. ISBN 0-375-40642-5.

- Hunter, William A. Forts on the Pennsylvania Frontier, 1753–1758. Originally published 1960; Wennawoods reprint, 1999.

- Stotz, Charles Morse. Outposts Of The War For Empire: The French and English In Western Pennsylvania: Their Armies, Their Forts, Their People 1749–1764. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2005. ISBN 0-8229-4262-3.

- Withers, Alexander Scott; Draper, Lyman Copeland (1895). Chronicles of Border Warfare. Stewart & Kidd Company.