National Assembly (France)

The National Assembly (French: Assemblée nationale; pronounced [asɑ̃ble nasjɔnal]) is the lower house of the bicameral French Parliament under the Fifth Republic, the upper house being the Senate (Sénat). The National Assembly's legislators are known as députés (French pronunciation: [depyˈte]; "delegate" or "envoy" in English; the word is an etymological cognate of the English word "deputy", which is the standard term for legislators in many parliamentary systems).

National Assembly Assemblée nationale | |

|---|---|

| 15th legislature of the French Fifth Republic | |

| |

| Type | |

| Type | of the French Parliament |

| History | |

| Founded | 4 October 1958 |

| Preceded by | National Assembly (French Fourth Republic) |

| Leadership | |

| Structure | |

| Seats | 577 seats |

| |

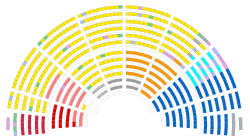

Political groups | Government

Neutral parties Opposition parties Vacant

|

| Elections | |

| First-past-the-post voting (577 seats, two-round system) | |

Last election | 11 and 18 June 2017 |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| Palais Bourbon, Paris | |

| Website | |

| www | |

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Politics of France |

|---|

|

|

|

|

Related topics

|

There are 577 députés, each elected by a single-member constituency through a two-round voting system. Thus, 289 seats are required for a majority. The assembly is presided over by a president (currently Richard Ferrand), normally from the largest party represented, assisted by vice-presidents from across the represented political spectrum. The term of the National Assembly is five years; however, the President of the Republic may dissolve the Assembly (thereby calling for new elections) unless it has been dissolved in the preceding twelve months. This measure has become rarer since the 2000 referendum reduced the presidential term from seven to five years: a President usually has a majority elected in the Assembly two months after the presidential election, and it would be useless for him/her to dissolve it for those reasons.

Following a tradition started by the first National Assembly during the French Revolution, the "left-wing" parties sit to the left as seen from the president's seat, and the "right-wing" parties sit to the right, and the seating arrangement thus directly indicates the political spectrum as represented in the Assembly. The official seat of the National Assembly is the Palais Bourbon on the banks of the river Seine; the Assembly also uses other neighbouring buildings, including the Immeuble Chaban-Delmas on the rue de l'Université. It is guarded by Republican Guards.

Relationships with the executive

The Constitution of the French Fifth Republic greatly increased the power of the executive at the expense of Parliament, compared to previous constitutions (Third and Fourth Republics).[2]

The President of the Republic can decide to dissolve the National Assembly and call for new legislative elections. This is meant as a way to resolve stalemates where the Assembly cannot decide on a clear political direction. This possibility is seldom exercised. The last dissolution was by Jacques Chirac in 1997, following from the lack of popularity of prime minister Alain Juppé; however, the plan backfired, and the newly elected majority was opposed to Chirac.

The National Assembly can overthrow the executive government (that is, the Prime Minister and other ministers) by a motion of no confidence (motion de censure). For this reason, the prime minister and his cabinet are necessarily from the dominant party or coalition in the assembly. In the case of a president and assembly from opposing parties, this leads to the situation known as cohabitation; this situation, which has occurred three times (twice under Mitterrand, once under Chirac), is likely to be rarer now that presidential and assembly terms are the same length.

While motions de censure are periodically proposed by the opposition following government actions that it deems highly inappropriate, they are purely rhetorical; party discipline ensures that, throughout a parliamentary term, the government is never overthrown by the Assembly.[3] Since the beginning of the Fifth Republic, there has only been one single successful motion de censure, in 1962 in hostility to the referendum on the method of election of the President,[4] and President Charles de Gaulle dissolved the Assembly within a few days.[5]

The government (the prime minister and the minister of relationships with parliament) used to set the priorities of the agenda for the assembly's sessions, except for a single day each month. In practice, given the number of priority items, it meant that the schedule of the assembly was almost entirely set by the executive; bills generally only have a chance to be examined if proposed or supported by the executive. This, however, was amended on 23 July 2008. Under the amended constitution, the government sets the priorities for two weeks in a month. Another week is designated for the assembly's "control" prerogatives (consisting mainly of verbal questions addressed to the government). And the fourth one is set by the assembly. Also, one day per month is set by a "minority" (group supporting the government but which is not the biggest group) or "opposition" (group having officially declared it did not support the government) group.

Legislators of the assembly can ask written or oral questions to ministers. The Wednesday afternoon 3 p.m. session of "questions to the Government" is broadcast live on television. Like Prime Minister's Questions in Britain, it is largely a show for the viewers, with members of the majority asking flattering questions, while the opposition tries to embarrass the government.[6]

Elections

Since 1988, the 577 deputies are elected by direct universal suffrage with a two-round system by constituency, for a five-year mandate, subject to dissolution. The constituencies each have approximately 100,000 inhabitants. The electoral law of 1986 specifies that variations of population between constituencies should not, in any case, lead to a constituency exceeding more than 20% the average population of the constituencies of the département.[7] However, districts were not redrawn between 1982 and 2009. As a result of population movements over that period, there were inequalities between the less populous rural districts and the urban districts. For example, the deputy for the most populous constituency, in the department of Val-d'Oise, represented 188,000 voters, while the deputy for the least populous constituency, in the department of Lozère, represented only 34,000. The constituencies were redrawn in 2009,[8] but this redistribution was controversial.[9] Among other controversial measures, it created eleven constituencies and seats for French residents overseas, albeit without increasing the overall number of seats beyond 577.[10][11]

.jpg)

To be elected in the first round of voting, a candidate must obtain at least 50% of the votes cast, with a turn-out of at least 25% of the registered voters on the electoral rolls. If no candidate is elected in the first round, those who poll in excess of 12.5% of the registered voters in the first-round vote are entered in the second round of voting. If no candidate comply such conditions, the two highest-placing candidates advance to second round. In the second round, the candidate who receives the most votes is elected. Each candidate is enrolled along with a substitute, who takes the candidate's place in the event of inability to represent the constituency, when the deputy becomes minister, for example.

The organic law of 10 July 1985 established a system of party-list proportional representation within the framework of the département. It was necessary within this framework to obtain at least 5% of the vote to elect an official. However, the legislative election of 1986, carried out under this system, gave France a new majority which returned the National Assembly to the plurality voting system described above.

Of the 577 elected deputies, 539 represent Metropolitan France, 27 represent the overseas departments and overseas collectivities, and 11 represent French residents overseas.[12]

Discussing and voting laws

The agenda of the National Assembly is mostly decided by the government but the assembly can also enforce its agenda. Indeed, the article 48 of the constitution guarantee at least a monthly session decided by the assembly.[13]

1. A law proposal

A law proposal is a document divided into 3 distinct parts: a title, an exposé des motifs and a dispositif. The exposé des motifs describe the arguments in favor of a modification of a given law or new measurements that are proposed. The dispositif is the normative part, which is developed within articles.[13]

A proposal for a law can be originated from the Prime minister or a member of the parliament. Certain laws must come from the government, including for example financial regulations.[14]

The proposition of law may pass through the National Assembly and Senate in an indifferent order, except for financial which must go through the assembly first or territorial organizational laws or laws for French living in foreign countries, which must first pass through the Senate.[15]

2. The deposit of a law

For an ordinary proposition of law, texts must be first reviewed by a permanent parliamentary commission or a special commission designated for this purpose. During the discussion in the commission or in plenary sessions in the assembly, the government and the parliament can add, modify or delete articles of the proposal. The text is thus amended. Amendments proposed by parliamentarian cannot mobilize further public funding. The government has to right to ask the assembly to pronounce themselves in one vote only with the amendments proposed or accepted by the government itself.[13]

Projects of propositions of laws will be examined succinctly by the two assembly- National Assembly and the Senate- until the text is identical. After the two lectures by the two chambers (or just one if the government decide to engage an acceleration of the text adoption - which can happen only in certain conditions) and without any accord, the Prime Minister or the two Presidents of the two chambers -conjointly with him- can convoke a special commission composed by an equal number of parliamentarians and senators to reach a compromise and propose a new text. The new proposition has to be approved by the government before being re-proposed to the two assemblies. No new amendments can be added except on the government’s approval. If the new proposal of law fails to be approved by the two chambers, the government can, after a new lecture by the National Assembly and the Senate, ask the National Assembly to rule a final judgement. In that case, the National Assembly can either take back the text elaborated by the special commission or the last one that they voted for – possibly modified by several amendments by the Senate.[13]

The president, on the government or the two assemblies’ proposal, can submit every law proposal as a referendum if it concerns the organization of public powers, reforms on the economy, social and environmental measures or every proposition that would have an impact on the well-functioning of the institutions. A referendum on the previous conditions can also be initiated by a fifth of the member of the parliament, supported by a tenth of the voters inscribed on the electoral lists.[16]

Finally, the laws are promulgated by the President. He may call for a new legislative deliberation of the law or one of its articles in front of the National Assembly, which cannot be denied.[13]

Conditions and privileges of deputies

Assembly legislators receive a salary of €7,043.69 per month. There is also the "compensation representing official expenses" (indemnité représentative de frais de mandat, IRFM) of €5,867.39 per month to pay costs related to the office, and finally a total of €8,949 per month to pay up to five employees. They also have an office in the Assembly, various perquisites in terms of transport and communications, social security, a pension fund, and unemployment insurance. Under Article 26 of the Constitution, deputies, like Senators, are protected by parliamentary immunity. In the case of an accumulation of mandates, a deputy cannot receive a wage of more than €9,779.11.

Accumulation of mandates and minimum age

The position of deputy of the National Assembly is incompatible with that of any other elected legislative position (Senator or since 2000, Member of European Parliament) or with some administrative functions (members of the Constitutional Council of France and senior officials such as prefects, magistrates, or officers who are ineligible for Department where they are stationed). Deputies may not have more than one local mandate (in a municipal, intercommunal, general, or regional council) in addition to their current mandate. Since the 2017 general election, deputies cannot hold an executive position in any local government (municipality, department, region). However, they can hold a part-time councillor mandate. As of July 2017, 58% of deputies hold such a seat. Since 1958, the mandate is also incompatible with a ministerial function. Upon appointment to the Government, the elected deputy has one month to choose between the mandate and the office. If he or she chooses the second option, then they are replaced by their substitute. One month after the end of his cabinet position, the deputy returns to his seat in the Assembly.

To be eligible to be elected to the National Assembly, one must be at least 18[17] years old, of French citizenship, and not subject to a sentence of deprivation of civil rights or to personal bankruptcy.

Eligibility conditions

1. Eligibility due to personal requirements

The essential conditions to run for elections are the following. First, a candidate must have French citizenship. Secondly, the minimum age required to run for a seat at the National Assembly is set at 18 years old.[18] The candidate must also have fulfilled his National Civic Day, a special day created to replace the military service.[19] Finally, a candidate under guardianship and curatorship cannot be elected at the assembly.[20]

Furthermore, a person cannot be elected if they were declared ineligible following fraudulent funding of a previous electoral campaign. Indeed, the voter would be considered as highly influenced and its decision making would be impacted. The sincerity of the results could thus not be regarded as viable and legitimate.[21]

2. Eligibility due to positions that a person may occupy

The député mandate cannot be cumulated with a mandate of senators, European deputy, member of the government or of the constitutional council.[18]

The député mandate is also incompatible with being a member of the military corps on duty, and with the exercised of one of the following mandates: regional councilor, councilor at the Assemblée de Corse, general councilor or being a municipal councilor of a municipality of a least or more than 3,500 inhabitants.[22] Prefects are also unable to be elected in France in every district they are exercising power or exercised power for less than three years before the date of the election.[23]

Since the 31st of March 2017, being elected national député is incompatible with local mandates such as mayors, president of a regional council or member of the departmental council.[24]

Current legislature

Parliamentary groups

| Parliamentary group | Members | Related | Total | President | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LREM | La République En Marche | 277 | 3 | 280 | Gilles Le Gendre | |

| LR | The Republicans | 98 | 6 | 104 | Damien Abad | |

| MoDem | Democratic Movement and affiliated | 40 | 6 | 46 | Patrick Mignola | |

| SOC | Socialists and associated | 24 | 4 | 28 | Valérie Rabault | |

| UDI | UDI and Independents | 19 | 0 | 19 | Jean-Christophe Lagarde | |

| LT | Libertés and Territories | 18 | 0 | 18 | Bertrand Pancher, Philippe Vigier | |

| AE | Act Together | 17 | 0 | 17 | Olivier Becht | |

| EDS | Ecology Democracy Solidarity | 17 | 0 | 17 | Paula Forteza, Matthieu Orphelin | |

| FI | La France Insoumise | 17 | 0 | 17 | Jean-Luc Mélenchon | |

| GDR | Democratic and Republican Left | 15 | 0 | 15 | André Chassaigne | |

| NI | Non-inscrits | – | – | 12 | – | |

Bureau of the National Assembly

| Post | Name | Constituency | Group | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vice President in charge of international relations |

Laetitia Saint-Paul | Maine-et-Loire's 4th | LREM | |

| Vice President in charge of representatives of interest groups and study groups |

Sylvain Waserman | Bas-Rhin's 2nd | MODEM | |

| Vice President in charge of communication and the press |

Hugues Renson | Paris's 13th | LREM | |

| Vice President in charge of the artistic and cultural heritage of the National Assembly |

David Habib | Pyrénées-Atlantiques's 3rd | SOC | |

| Vice President in charge of the application of the deputy's statute |

Annie Genevard | Doubs's 5th | LR | |

| Vice President in charge of the admissibility of proposals of law |

Marc Le Fur | Côtes-d'Armor's 3rd | LR | |

| Quaestor | Florian Bachelier | Ille-et-Vilaine's 8th | LREM | |

| Laurianne Rossi | Hauts-de-Seine's 11th | LREM | ||

| Éric Ciotti | Alpes-Maritimes's 1st | LR | ||

| Secretary | Lénaïck Adam | French Guiana's 2nd | LREM | |

| Ramlati Ali | Mayotte's 1st | LREM | ||

| Danielle Brulebois | Jura's 1st | LREM | ||

| Luc Carvounas | Val-de-Marne's 9th | SOC | ||

| Lionel Causse | Landes's 2nd | LREM | ||

| Alexis Corbière | Seine-Saint-Denis's 7th | FI | ||

| Laurence Dumont | Calvados's 2nd | SOC | ||

| Marie Guévenoux | Essonne's 9th | LREM | ||

| Annaïg Le Meur | Finistère's 1st | LREM | ||

| Sophie Mette | Gironde's 9th | MoDem | ||

| Gabriel Serville | French Guiana's 1st | GDR | ||

| Guillaume Vuilletet | Val-d'Oise's 2nd | LREM | ||

Presidencies of committees

| Standing committees | President | Group | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural and Education Affairs Committee | Bruno Studer | LREM | |

| Economic Affairs Committee | Roland Lescure | LREM | |

| Foreign Affairs Committee | Marielle de Sarnez | MoDem | |

| Social Affairs Committee | Brigitte Bourguignon | LREM | |

| National Defence and Armed Forces Committee | Françoise Dumas | LREM | |

| Sustainable Development, Spatial and Regional Planning Committee | Barbara Pompili | LREM | |

| Finance, General Economy and Budgetary Monitoring Committee | Éric Woerth | LR | |

| Constitutional Acts, Legislation and General Administration Committee | Yaël Braun-Pivet | LREM | |

| Other committee | President | Group | |

| European Affairs Committee | Pieyre-Alexandre Anglade | LREM | |

Deputies

- List of deputies of the 11th National Assembly of France

- List of deputies of the 12th National Assembly of France

- List of deputies of the 13th National Assembly of France

- List of deputies of the 14th National Assembly of France

- List of deputies of the 15th National Assembly of France

See also

Notes and references

- "Déclaration politique du groupe Ecologie Démocratie Solidarité" [Political declaration of the Ecology Democracy Solidarity group]. Ecology Democracy Solidarity (in French). Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- William G. Andrews (August 1978). Legislative Studies Quarterly (ed.). "The Constitutional Prescription of Parliamentary Procedures in Gaullist France". p. 465–506. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "La motion de censure : véritable moyen de contrôle?" [Motion of no confidence: a real mean of control?]. vie-publique.fr (in French). 30 June 2018.

- "ASSEMBLÉE NATIONALE, CONSTITUTION DU 4 . OCTOBRE 1958" [NATIONAL ASSEMBLY, CONSTITUTION OF 4. OCTOBER 1958] (PDF) (in French). 4 October 1962. p. 3268. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "Fac-similé JO du 10/10/1962". legifrance.gouv.fr (in French). p. 9818. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Anne-Laure Nicot (January 2007). E.N.S. Editions (ed.). "La démocratie en questions: L'usage stratégique de démocratie et de ses dérivés dans les questions au gouvernement de la 11e Législature" [Democracy in question. The strategic use of democracy and its derivatives in questions to the government of the 11th Legislature] (in French). p. 9–21. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Stéphane Mandard (7 June 2007). En 2005, un rapport préconisait le remodelage des circonscriptions avant les législatives de 2007 [In 2005, a report recommended the redesign of the constituencies before the 2007 legislative elections]. Le Monde.

- "Ordonnance n° 2009-935 du 29 juillet 2009 portant répartition des sièges et délimitation des circonscriptions pour l'élection des députés" [Order n° 2009-935 of 29 July 2009 relating to the distribution of seats and the delimitation of constituencies for the election of deputies] (in French). Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Pierre Salvere. "La révision des circonscriptions électorales: Un échec démocratique annoncé" [Electoral districts review: an announced democratic failure]. Fondation Terra Nova (in French). Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "Elections 2012 – Votez à l'étranger" [Elections 2012 - Vote abroad]. legifrance.gouv.fr (in French). Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "Redécoupage électoral – 11 députés pour les Français de l'étranger" [Electoral cutting - 11 deputies for French citizens abroad]. Le Petit Journal. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "Code électoral – Article LO119" [Electoral code - Article LO119]. legifrance.gouv.fr (in French). Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "Les Propositions De Loi, Du DEPOT à La Promulgation" [Bills of law, from filing to promulgation]. Assemblee-nationale.fr. (in French). Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "Comment crée-t-on une loi?" [How do you make a law?]. Libération (in French). 9 June 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "The Senate votes the law – Taking the initiative". Senat.fr. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Durand, A (7 December 2018). "Qu'est-ce que le référendum d'initiative citoyenne (RIC) demandé par des « gilets jaunes » ?" [What is the citizens' initiative referendum (RIC) requested by "yellow vests"?]. Le Monde (in French). Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "Quelles sont les conditions nécessaires pour devenir député ou sénateur ?" [What are the conditions for becoming a deputy or senator?]. vie-publique.fr (in French). 30 June 2018. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "Code électoral – Article LO137" [Electoral code - Article LO137]. legifrance.gouv.fr (in French). Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "Code électoral – Article L45" [Electoral code - Article L45]. legifrance.gouv.fr (in French). Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "Code électoral – Article LO129" [Electoral code - Article LO129]. legifrance.gouv.fr (in French). Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Nationale, A. "Fiche de synthèse n°14 : L'élection des députés" [Summary sheet n° 14: Election of deputies]. Assemblee-nationale.fr. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "Code électoral – Article LO141" [Electoral code - Article LO141]. legifrance.gouv.fr (in French). Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "Code électoral – Article LO132" [Electoral code - Article LO132]. legifrance.gouv.fr (in French). Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "LOI Organique N° 2014-125 Du 14 Février 2014 Interdisant Le Cumul De Fonctions Exécutives Locales Avec Le Mandat De Député Ou De Sénateur" [Organic LAW n° 2014-125 of 14 February 2014 prohibiting the combination of local executive functions with the mandate of deputy or senator]. Legifrance.gouv.fr. (in French). Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "Effectif des groupes politiques" [Membership of political groups] (in French). Assemblée nationale. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "NOTICES ET PORTRAITS, Quinzième législature" [INSTRUCTIONS AND PORTRAITS, Fifteenth legislature] (PDF). Assemblée nationale. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to National Assembly of France. |

- Official website (English)