New Zealand art

New Zealand art consists of the visual and plastic arts (including architecture, woodwork, textiles, and ceramics) originating from New Zealand. It comes from different traditions: indigenous Māori art, that of the early European (or Pākehā) settlers, and later immigrants from Pacific, Asian, and European countries. Owing to New Zealand's geographic isolation, in the past many artists had to leave home in order to make a living. The visual arts flourished in the latter decades of the 20th century as many New Zealanders became more culturally sophisticated.

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of New Zealand |

|---|

|

|

Traditions |

|

Festivals |

|

Art

|

|

Literature |

|

Media |

|

Monuments

|

|

Prehistoric art

Charcoal drawings can be found on limestone rock shelters in the centre of the South Island, with over 500 sites[1] stretching from Kaikoura to North Otago. The drawings are estimated to be between 500 and 800 years old, and portray animals, humans and legendary creatures, possibly stylised reptiles.[2] Some of the birds pictured are extinct, including moa and Haast's eagles. They were drawn by early Māori, but by the time Europeans arrived, local inhabitants did not know the origins of the drawings.[3]

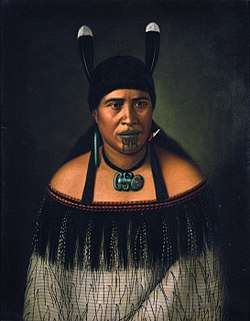

Traditional Māori art

Māori visual art consists primarily of four forms: carving, tattooing (ta moko), weaving, and painting. It was rare for any of these to be purely decorative; traditional Māori art was highly spiritual and in a pre-literate society conveyed information about spiritual matters, ancestry, and other culturally important topics. The creation of art was governed by the rules of tapu. Styles varied from region to region: the style now sometimes seen as 'typical' in fact originates from Te Arawa, who maintained a strong continuity in their artistic traditions thanks partly to early engagement with the tourist industry. Most traditional Māori art was highly stylised and featured motifs such as the spiral, the chevron and the koru. The colours black, white and red dominated.

Carving

Carving was done in three media: wood, bone, and stone. Arguably ta moko was another form of carving. Wood carvings were used to decorate houses, fencepoles, containers, taiaha and other objects. The most popular type of stone used in carving was pounamu (greenstone), a form of jade, but other kinds were also used, especially in the North Island, where pounamu was not widely available. Both stone and bone were used to create jewellery such as the hei-tiki. Large scale stone face carvings were also sometimes created. The introduction of metal tools by Europeans allowed more intricacy and delicacy, and caused stone and bone fish hooks and other tools to become purely decorative. Carving is traditionally a tapu activity performed by men only.[4]

Ta moko

Ta moko is the art of traditional Māori tattooing, done with a chisel. Men were tattooed on many parts of their bodies, including faces, buttocks and thighs. Women were usually tattooed only on the lips and chin. Moko conveyed a person's ancestry. The art declined in the 19th century following the introduction of Christianity, but in recent decades has undergone a revival. Although modern moko are in traditional styles, most are carried out using modern equipment. Body parts such as the arms, legs and back are popular locations for modern moko, although some are still on the face.

Weaving

Weaving was used to create numerous things, including wall panels in meeting houses and other important buildings, as well as clothing and bags (kete). While many of these were purely functional, others were true works of art taking hundreds of hours to complete, and often given as gifts to important people. Cloaks in particular could be decorated with feathers and were the mark of an important chief. In pre-European times the main medium for weaving was flax, but following the arrival of Europeans cotton, wool and other textiles were also used, especially in clothing. The extinction and endangerment of many New Zealand birds has made the feather cloak a more difficult item to produce. Weaving was primarily done by women.

Painting

Although the oldest forms of Māori art are rock paintings, in 'classical' Māori art, painting was not an important art form. It was mainly used as a minor decoration in meeting houses, in stylised forms such as the koru. Europeans introduced Māori to their more figurative style of art, and in the 19th century less stylised depictions of people and plants began to appear on the walls of meeting houses in place of traditional carvings and woven panels. The introduction of European paints also allowed traditional painting to flourish, as brighter and more distinct colours could be produced.

Explorer art

Europeans began producing art in New Zealand as soon as they arrived, with many exploration ships including an artist to record newly discovered places, people, flora and fauna. The first European work of art made in New Zealand was a drawing by Isaac Gilsemans, the artist on Abel Tasman's expedition of 1642.[5][6]

Sir Joseph Banks[7][8] and Sydney Parkinson of Captain James Cook's ship Endeavour produced the first realistic depictions of Māori people, New Zealand landscapes, and indigenous flora and fauna in 1769. William Hodges was the artist on HMS Resolution in 1773, and John Webber on HMS Resolution in 1777. Their works captured the imagination of Europeans and were an influence in the 19th century movement of art towards naturalism.[9]

Cook's artists' paintings and descriptions of moko sparked an interest in the subject in Europe, and led to the tattoo becoming a tradition of the British Navy.[10]

19th century Pākehā art

Early 19th-century artists were for the most part visitors to New Zealand, not residents. Some, such as James Barry, who painted the Ngare Raumati chief Rua in 1818, and Thomas Kendall with the chiefs Hongi Hika and Waikato in 1820, did not visit New Zealand at all, instead painting his subjects when they visited Britain.[11][12]

Landscape art was popular with early colonisers, and prints were widely used to promote settlement in New Zealand. Notable landscape artists included Augustus Earle, who visited New Zealand in 1827-28,[13][14] and William Fox, who later became Premier.[15] The first oil portraits of Māori Chiefs with full Tā moko in New Zealand were painted by the portrait artist William Beetham.[16] As colonisation developed a small but derivative art scene began based mostly on landscapes. However the most successful artists of this period, Charles Goldie and Gottfried Lindauer were noted primarily for their portraits of Māori. Most notable Pākehā artists of their period worked in two dimensions; although there was some sculpture this was of limited notability.

Photography in New Zealand also began at this time and, like painting, initially concentrated mostly on landscape and Māori subjects.

20th century

.jpg)

Creation of a distinct New Zealand art

Beginning in the 1930s, many Pākehā (New Zealanders not of Maori origin, usually of European ancestry) attempted to create a distinctive New Zealand style of art. Many, such as Rita Angus, continued to work on landscapes, with attempts made to depict New Zealand's harsh light. Others appropriate Māori artistic styles; for example Gordon Walters created many paintings and prints based on the koru. New Zealand's most highly regarded 20th-century artist was Colin McCahon, who attempted to use international styles such as cubism in New Zealand contexts. His paintings depicted such things as the Angel Gabriel in the New Zealand countryside. Later works such as the Urewera triptych engaged with the contemporary Māori protest movement.

Māori cultural renaissance

From the early 20th century, politician Āpirana Ngata fostered a renewal of traditional Māori art forms, for example establishing a school of Māori arts in Rotorua.

Late 20th and early 21st centuries

The visual arts flourished in the later decades of the 20th century, with the increased cultural sophistication of many New Zealanders. Many Māori artists became highly successful blending elements of Māori culture with European modernism. Ralph Hotere was New Zealand's highest selling living artist, but other such as Shane Cotton and Michael Parekowhai are also very successful. Many contemporary Maori artists reference ancient myths and cultural practices in their work such as Derek Lardelli, Lisa Reihana, Sofia Minson, Te Rongo Kirkwood, Robyn Kahukiwa, Aaron Kereopa, Rangi Kipa, John Miller, Kura Te Waru Rewiri, Tracey Tawhiao, Roi Toia, Shane Hansen, John Bevan Ford, Jennifer Rendall, Todd Couper, Manos Nathan, Wayne Youle, Lyonel Grant, Wi Taepa and David Teata.

Art organisations and museums

Creative New Zealand is the national agency for the development of the arts in New Zealand.[17]

The National Art Gallery of New Zealand was established in 1936, and was amalgamated into the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa in 1992. The Auckland Art Gallery is New Zealand's largest art institution with a collection numbering over 15,000 works,[18] including major holdings of New Zealand historic, modern and contemporary art, and outstanding works by Māori and Pacific Island artists.

Waikato Museum, Te Whare Taonga O Waikato located on the banks of the Waikato River in downtown Hamilton.[19]

Art schools

New Zealand has three university-based fine art schools: Ilam School of Fine Arts at the University of Canterbury (formerly Canterbury College School of Art) was founded in 1882, Elam School of Fine Arts at the University of Auckland was founded in 1890 and Massey School of Fine Arts founded in 1885, but was not officially a university institution until 2000.[20] There are also several other tertiary level fine arts schools not affiliated to universities.

Notes

- "Very Old Maori Rock Drawings". Natural Heritage Collection. Archived from the original on 2009-02-24. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

- "The SRARNZ Logo". Society for Research on Amphibians and Reptiles in New Zealand. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

- Keith, Hamish (2007). The Big Picture: A history of New Zealand art from 1642. pp. 11–16. ISBN 978-1-86962-132-2.

- "Janet McAllister: Sacred practice of creating art". nzherald.co.nz. 2011-10-15. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- "A view of the Murderers' Bay". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 2009-02-09.

- Keith, 2007, pp 16-23

- "The Endeavour Journal of Joseph Banks 1768–1771 (Volume One)". Retrieved 2009-03-14.

- "The Endeavour Journal of Joseph Banks 1768–1771 (Volume Two)". Retrieved 2009-03-14.

- Keith, 2007, pp 23-28

- Keith, 2007, p 35

- Keith, 2007, pp 49-50

- "The Rev Thomas Kendall and the Maori chiefs Hongi and Waikato 1820". National Library of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 2008-10-14. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

- Keith, 2007, pp 52-56, 71

- Earle, Augustus (1832). A narrative of a nine months' residence in New Zealand in 1827: together with a journal of a residence in Tristan D'Acunha, an island situated between South America and the Cape of Good Hope. Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green & Longman.

- "William Fox - Painter and Premier". National Library of New Zealand. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

- http://www.nzportraitgallery.org.nz/whats-on/te-rū-movers-shakers-early-new-zealand-portraits-by-william-beetham

- "Arts Council of New Zealand Toi Aotearoa homepage". Creative New Zealand.

- Auckland Art Gallery. "Collection overview and policies". Auckland Art Gallery website. Auckland Art Gallery. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- "About us - Waikato Museum". waikatomuseum.co.nz. Retrieved 2018-12-19.

- A. H. McLintock (ed) (2007-09-18). "Art Schools - Elam School of Fine Arts". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand (1966). Retrieved 2009-02-01.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

References

- Keith, Hamish (2007). The Big Picture: A history of New Zealand art from 1642. pp. 11–16. ISBN 978-1-86962-132-2.

- Johnstone, Christopher (2013). Landscape Paintings of New Zealand. A Journey from North to South. ISBN 978-1-77553-011-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Art of New Zealand. |

- Art and photography at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

- History of New Zealand painting, NZHistory.net.nz