Freiburg im Breisgau

Freiburg im Breisgau (German: [ˈfʁaɪbʊʁk ʔɪm ˈbʁaɪsɡaʊ] (![]()

Freiburg im Breisgau | |

|---|---|

View over Freiburg | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

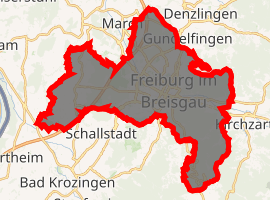

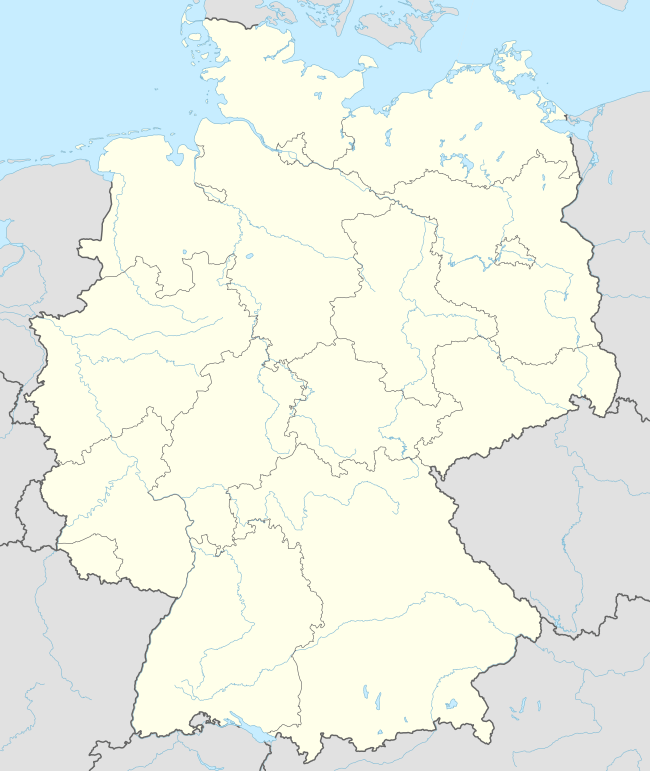

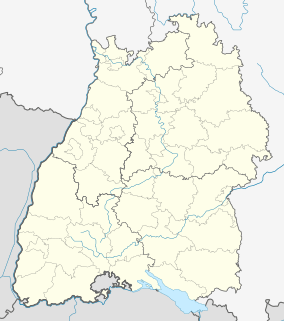

Location of Freiburg im Breisgau

| |

Freiburg im Breisgau  Freiburg im Breisgau | |

| Coordinates: 47°59′N 7°51′E | |

| Country | Germany |

| State | Baden-Württemberg |

| Admin. region | Freiburg |

| District | Stadtkreis |

| Subdivisions | 41 districts |

| Government | |

| • Lord Mayor | Martin Horn (Ind.) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 153.07 km2 (59.10 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 278 m (912 ft) |

| Population (2018-12-31)[1] | |

| • Total | 230,241 |

| • Density | 1,500/km2 (3,900/sq mi) |

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) |

| Postal codes | 79098–79117 |

| Dialling codes | 0761, 07664, 07665 |

| Vehicle registration | FR |

| Website | |

History

Freiburg was founded by Konrad and Duke Berthold III of Zähringen in 1120 as a free market town;[5] hence its name, which translates to "free (or independent) town". Frei means "free", and Burg, like the modern English word "borough", was used in those days for an incorporated city or town, usually one with some degree of autonomy.[6] The German word Burg also means "a fortified town", as in Hamburg. Thus, it is likely that the name of this place means a "fortified town of free citizens".

This town was strategically located at a junction of trade routes between the Mediterranean Sea and the North Sea regions, and the Rhine and Danube rivers. In 1200, Freiburg's population numbered approximately 6,000 people. At about that time, under the rule of Bertold V, the last duke of Zähringen, the city began construction of its Freiburg Münster cathedral on the site of an older parish church.[5] Begun in the Romanesque style, it was continued and completed 1513 for the most part as a Gothic edifice. In 1218, when Bertold V died, then Egino V von Urach, the count of Urach assumed the title of Freiburg's count as Egino I von Freiburg.[5] The city council did not trust the new nobles and wrote down its established rights in a document. At the end of the thirteenth century there was a feud between the citizens of Freiburg and their lord, Count Egino II of Freiburg. Egino II raised taxes and sought to limit the citizens' freedom, after which the Freiburgers used catapults to destroy the count's castle atop the Schloßberg, a hill that overlooks the city center. The furious count called on his brother-in-law the Bishop of Strasbourg, Konradius von Lichtenberg, for help. The bishop responded by marching with his army to Freiburg.

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1385 | 9,000 | — |

| 1620 | 10,000 | +11.1% |

| 1871 | 24,668 | +146.7% |

| 1900 | 61,504 | +149.3% |

| 1910 | 83,324 | +35.5% |

| 1919 | 87,946 | +5.5% |

| 1925 | 90,475 | +2.9% |

| 1933 | 99,122 | +9.6% |

| 1939 | 110,110 | +11.1% |

| 1950 | 109,717 | −0.4% |

| 1961 | 145,016 | +32.2% |

| 1970 | 162,222 | +11.9% |

| 1987 | 178,672 | +10.1% |

| 2011 | 209,628 | +17.3% |

| 2017 | 229,636 | +9.5% |

| source:[7] | ||

_4029.jpg)

According to an old Freiburg legend, a butcher named Hauri stabbed the Bishop of Strasbourg to death on 29 July 1299. It was a Pyrrhic victory, since henceforth the citizens of Freiburg had to pay an annual expiation of 300 marks in silver to the count of Freiburg until 1368. In 1366 the counts of Freiburg made another failed attempt to occupy the city during a night raid. Eventually the citizens were fed up with their lords, and in 1368 Freiburg purchased its independence from them. The city turned itself over to the protection of the Habsburgs, who allowed the city to retain a large measure of freedom. Most of the nobles of the city died in the battle of Sempach (1386). The patrician family Schnewlin took control of the city until the guildsmen revolted. The guilds became more powerful than the patricians by 1389.

The silver mines in Mount Schauinsland provided an important source of capital for Freiburg. This silver made Freiburg one of the richest cities in Europe, and in 1327 Freiburg minted its own coin, the Rappenpfennig. In 1377 the cities of Freiburg, Basel, Colmar, and Breisach entered into a monetary alliance known as the Genossenschaft des Rappenpfennigs (Rappenpfennig Collective). This alliance facilitated commerce among the cities and lasted until the end of the sixteenth century. There were 8,000–9,000 people living in Freiburg between the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, and 30 churches and monasteries. At the end of the fourteenth century the veins of silver were dwindling, and by 1460 only approximately 6,000 people still lived within Freiburg's city walls.

A university city, Freiburg evolved from its focus on mining to become a cultural centre for the arts and sciences. It was also a commercial center. The end of the Middle Ages and the dawn of the Renaissance was a time of both advances and tragedy for Freiburg.

In 1457, Albrecht VI, Regent of Further Austria, established Albert-Ludwigs-Universität, one of Germany's oldest universities. In 1498, Emperor Maximilian I held a Reichstag in Freiburg. In 1520, the city ratified a set of legal reforms, widely considered the most progressive of the time. The aim was to find a balance between city traditions and old Roman Law. The reforms were well received, especially the sections dealing with civil process law, punishment, and the city's constitution.

In 1520, Freiburg decided not to take part in the Reformation and became an important centre for Catholicism on the Upper Rhine. Erasmus moved here after Basel accepted the Reformation.

In 1536, a strong and persistent belief in witchcraft led to the city's first witch-hunt. The need to find a scapegoat for calamities such as the Black Plague, which claimed 2,000 area residents (25% of the city population) in 1564, led to an escalation in witch-hunting that reached its peak in 1599. A plaque on the old city wall marks the spot where burnings were carried out.

The seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries were turbulent times for Freiburg. At the beginning of the Thirty Years' War there were 10,000–14,000 citizens in Freiburg; by its end only 2,000 remained. During this war and other conflicts, the city belonged at various times to the Austrians, the French, the Swedes, the Spaniards, and various members of the German Confederation. Between 1648 and 1805, when the city was not under French occupation it was the administrative headquarters of Further Austria, the Habsburg territories in the southwest of Germany. In 1805, the city, together with the Breisgau and Ortenau areas, became part of Baden.

In 1827, when the Archdiocese of Freiburg was founded, Freiburg became the seat of a Catholic archbishop.

_jm10177.jpg)

On 22 October 1940, the Nazi Gauleiter of Baden, Robert Heinrich Wagner, ordered the deportation of all of Baden's and 350 of Freiburg's Jewish population. They were deported to Camp Gurs in the south of France, where many died. On 18 July 1942, the remaining Baden and Freiburg Jews were transferred to Auschwitz in Nazi-occupied Poland, where almost all were murdered.[8] A living memorial has been created in the form of the 'footprint' in marble on the site of the city's original synagogue, which was burned down by the Nazi Germans on 9 November 1938, during the pogrom known as Kristallnacht. The memorial is a children's paddling pool and contains a bronze plaque commemorating the original building and the Jewish community which perished. The pavements of Freiburg carry memorials to individual victims, in the form of brass plates outside their former residences.

Freiburg was heavily bombed during World War II. In May 1940, aircraft of the Luftwaffe mistakenly dropped approximately 60 bombs on Freiburg near the railway station, killing 57 people.[9] On 27 November 1944, a raid by more than 300 bombers of RAF Bomber Command (Operation Tigerfish) destroyed a large portion of the city centre, with the notable exception of the Münster, which was only lightly damaged. After the war, the city was rebuilt on its medieval plan.

It was occupied by the French Army on 21 April 1945, and Freiburg was soon allotted to the French Zone of Occupation. In December 1945 Freiburg became the seat of government for the German state Badenia, which was merged into Baden-Württemberg in 1952. The French Army maintained a presence in Freiburg until 1991, when the last French Army division left the city, and left Germany.

On the site of the former French Army base, a new neighborhood for 5,000 people, Vauban, began in the late 1990s as a "sustainable model district". Solar power provides electricity to many of the households in this small community.

Points of interest

Because of its scenic beauty, relatively warm and sunny climate, and easy access to the Black Forest, Freiburg is a hub for regional tourism. In 2010, Freiburg was voted as the Academy of Urbanism's European City of the Year in recognition of the exemplary sustainable urbanism it has implemented over the past several decades.

The longest cable car run in Germany, which is 3.6 kilometres (2.2 mi) long, runs from Günterstal up to a nearby mountain called Schauinsland.

The city has an unusual system of gutters (called Freiburg Bächle) that run throughout its centre. These Bächle, once used to provide water to fight fires and feed livestock, are constantly flowing with water diverted from the Dreisam. They were never intended to be used for sewage, and even in the Middle Ages such use could lead to harsh penalties. During the summer, the running water provides natural cooling of the air, and offers a pleasant gurgling sound. It is said that if one accidentally falls or steps into a Bächle, they will marry a Freiburger, or 'Bobbele'.

The Augustinerplatz is one of the central squares in the old city. Formerly the location of an Augustinian monastery that became the Augustiner Museum in 1921, it is now a popular social space for Freiburg's younger residents. It has a number of restaurants and bars, including the local brewery 'Feierling', which has a Biergarten. On warm summer nights, hundreds of students gather here.

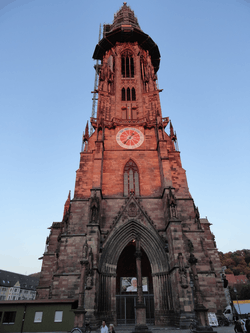

At the centre of the old city is the Münsterplatz or Cathedral Square, Freiburg's largest square. A farmers market is held here every day except Sundays. This is the site of Freiburg's Münster, a gothic minster cathedral constructed of red sandstone, built between 1200 and 1530 and noted for its towering spire.

The Historical Merchants' Hall (Historisches Kaufhaus), is a Late Gothic building on the south side of Freiburg's Münsterplatz. Built between 1520 and 1530, it was once the center of the financial life of the region. Its façade is decorated with statues and the coat of arms of four Habsburg emperors.

The Altes Rathaus, or old city hall, was completed in 1559 and has a painted façade. The Platz der alten Synagoge "Old Synagogue Square" is one of the more important squares on the outskirts of the historic old city. The square was the location of a synagogue until it was destroyed on Kristallnacht in 1938. Zum Roten Bären, the oldest hotel in Germany, is located along Oberlinden near the Swabian Gate.

The Siegesdenkmal, or victory monument, is a monument to the German victory in the Franco-Prussian War in 1871. It is situated at the northern edge of the historic city center of Freiburg, and was built by Karl Friedrich Moest. In everyday language of people living in Freiburg, it serves as an orientation marker or as a meeting place.

To the east of the city centre, the Schlossberg hill provides extensive views over the city and surrounding region. The castle (Schloss) from which the hill takes its name was demolished in the 1740s, and only ruins remain. Schlossberg retained its importance to the city, however, and 150 years ago the city leaders opened up walks and views to make the mountain available to the public. Today, the Schlossbergbahn funicular railway connects the city centre to the hill.[10]

Other museums in the city include the Archaeology Colombischlössle Museum.

List of major sights

- Arboretum Freiburg-Günterstal, an arboretum in the suburb of Günterstal

- Freiburg Botanic Garden

- University of Freiburg

- University Library Freiburg, the newly renovated library features a modern design

- The Whale House, which, in Dario Argento's 1977 horror film Suspiria, served as the Dance Academy, the film's central location

- Augustiner Museum

- Freiburg Munster

- Schauinsland

- Schlossberg (Freiburg)

- Colombischlössle Archeological Museum

- Green Spaces in Freiburg

- Vauban, Freiburg, a sustainable eco-community

- Cobblestone mosaics (Freiburg im Breisgau)

- Kybfelsen castle

Geography

Freiburg is bordered by the Black Forest mountains Rosskopf and Bromberg to the east, Schönberg and Tuniberg to the south, with the Kaiserstuhl hill region to the west.

Climate

Köppen climate classification classifies its climate as oceanic (Cfb). However, it is close to being humid subtropical (Cfa) due to the mean temperatures in July and August just under 22 °C (72 °F). Marine features are limited however, as a result of its vast distance from oceans and seas. As a result, summers have a significant subtropical influence as the inland air heats up. Thus July and August are, along with Karlsruhe, the warmest within Germany. Winters are moderate but usually with frequent frosts. However, more year-round rain occurs than in the Rhine plateau because of the closeness to the Black Forest. The city is close to the Kaiserstuhl, a range of hills of volcanic origin located a few miles away which is one of the warmest places in Germany and therefore considered as a viticultural area.

| Climate data for Freiburg 2015–2020, sunshine 2015–2020, extremes 1949–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18.8 (65.8) |

21.9 (71.4) |

25.7 (78.3) |

29.4 (84.9) |

33.7 (92.7) |

36.5 (97.7) |

38.3 (100.9) |

40.2 (104.4) |

33.9 (93.0) |

30.8 (87.4) |

23.2 (73.8) |

21.7 (71.1) |

40.2 (104.4) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 5.7 (42.3) |

7.9 (46.2) |

12.6 (54.7) |

16.7 (62.1) |

20.3 (68.5) |

25.0 (77.0) |

27.8 (82.0) |

27.5 (81.5) |

22.3 (72.1) |

16.2 (61.2) |

10.2 (50.4) |

7.9 (46.2) |

16.7 (62.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.8 (37.0) |

4.0 (39.2) |

7.2 (45.0) |

10.6 (51.1) |

14.5 (58.1) |

19.0 (66.2) |

21.3 (70.3) |

21.0 (69.8) |

16.1 (61.0) |

11.4 (52.5) |

6.7 (44.1) |

4.6 (40.3) |

11.6 (52.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 0.0 (32.0) |

0.1 (32.2) |

1.9 (35.4) |

4.6 (40.3) |

8.8 (47.8) |

13.8 (56.8) |

14.8 (58.6) |

14.4 (57.9) |

10.0 (50.0) |

6.6 (43.9) |

3.1 (37.6) |

1.3 (34.3) |

6.6 (43.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −18 (0) |

−21.6 (−6.9) |

−11.9 (10.6) |

−5.2 (22.6) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

3.2 (37.8) |

5.3 (41.5) |

4.5 (40.1) |

0.6 (33.1) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

−10.4 (13.3) |

−19.9 (−3.8) |

−21.6 (−6.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 44.5 (1.75) |

42.9 (1.69) |

36.7 (1.44) |

77 (3.0) |

96.2 (3.79) |

76.3 (3.00) |

52.5 (2.07) |

53.4 (2.10) |

45.4 (1.79) |

49.0 (1.93) |

66.2 (2.61) |

35.9 (1.41) |

676.1 (26.62) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 3.6 (1.4) |

1.0 (0.4) |

2.0 (0.8) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.76 (0.3) |

0.76 (0.3) |

5.1 (2.0) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 19.7 | 11.9 | 13.9 | 14.5 | 13.2 | 12.9 | 11.8 | 11.4 | 10.3 | 12.9 | 13.9 | 13.5 | 159.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 58 | 97 | 151 | 190 | 204 | 240 | 266 | 238 | 189 | 114 | 61 | 71 | 1,879 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 1.7 | 3.4 | 4.9 | 6.2 | 6.6 | 8.2 | 8.9 | 7.8 | 6.4 | 3.7 | 2.1 | 2.4 | 5.2 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Source 1: Weatheronline.de[11] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Meteociel.fr[12] | |||||||||||||

| Largest groups of foreigners by country of origin[13] | |

| Nationality | Population (2018) |

|---|---|

| 3,165 | |

| 2,598 | |

| 2,031 | |

| 1,756 | |

| 1,586 | |

| 1,558 | |

| 1,383 | |

| 1,149 | |

| 1,066 | |

| 1,042 | |

Government

Freiburg is known as an "eco-city". It has attracted the Bundesamt für Strahlenschutz, solar industries, and research; the Greens have a stronghold there (the strongest in any major German city; up to 35% of the overall city vote, in some neighbourhoods reaching 40% or more in the 2012 national elections). The newly built neighbourhoods of Vauban and Rieselfeld were developed and built according to the idea of sustainability. The citizens of Freiburg are known in Germany for their love of cycling and recycling.[14]

The former mayor (Oberbürgermeister), Dieter Salomon (in office 2002–2018), was the first member of Bündnis 90/Die Grünen to hold such an office in a city with more than 100,000 inhabitants.

In May 2018, Martin Horn, an independent candidate formerly associated with the SPD and supported by the SPD and FDP, became mayor of Freiburg, having received 34.7% in the first round of voting and 44.2% in the second.[15] During his post-election party, he was punched in the face by a local man with known psychiatric problems.[16]

In June 1995, the Freiburg city council adopted a resolution that it would permit construction only of "low-energy buildings" on municipal land, and all new buildings must comply with certain "low energy" specifications. Low-energy housing uses solar power passively as well as actively. In addition to solar panels and collectors on the roof, providing electricity and hot water, many passive features use the sun's energy to regulate the temperature of the rooms.[14]

Freiburg is host to a number of international organisations, in particular, ICLEI – Local Governments for Sustainability, International Solar Energy Society, and the City Mayors Foundation.[17]

The composition of Freiburg city council is as follows:

| Party | Seats | |

|---|---|---|

| Alliance '90/The Greens | 11 | |

| Christian Democratic Union | 9 | |

| Social Democratic Party | 8 | |

| Left List / Solidarity City | 4 | |

| Free Voters | 3 | |

| Livable Freiburg | 3 | |

| Free Democratic Party | 2 | |

| Culture List | 2 | |

| Young Freiburg | 2 | |

| Green Alternative Freiburg | 1 | |

| Independent Women | 1 | |

| The Party | 1 | |

| Christians for Freiburg | 1 | |

| TOTAL | 48 | |

Education

Freiburg is a center of academia and research with numerous intellectual figures and Nobel Laureates having lived, worked, and taught there.

The city houses one of the oldest and most renowned of German universities, the Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg, as well as its medical center. Home to some of the greatest minds of the West, including such eminent figures as Johann Eck, Max Weber, Edmund Husserl, Martin Heidegger, and Friedrich Hayek, it is one of Europe's top research and teaching institutions.

Freiburg also plays host to various other educational and research institutes, such as the Freiburg University of Education, the Protestant University for Applied Sciences Freiburg, Freiburg Music Academy, the Catholic University of Applied Sciences Freiburg, the International University of Cooperative Education IUCE, three Max Planck institutes, and five Fraunhofer institutes.

The city is home to the IES Abroad European Union program, which allows students to study the development and activities of the EU.[18][19]

The DFG / LFA Freiburg, a French-German high school established by the 1963 Élysée Treaty, is in the city.

Religion

Christianity

Freiburg belonged to Austria until 1805 and because of this stayed Catholic, even though surrounding villages like Haslach, Opfingen, Tiengen, and the surrounding land ruled by the Margrave of Baden turned Protestant as a result of the Reformation. The city was part of the Diocese of Konstanz until 1821. That same year, Freiburg became an episcopal see of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Freiburg. Due to a dispute between the government of Baden and the Holy See, the archbishop officially took office in 1827.

The borders of the archdiocese correspond with the borders of the former province of Baden and the former Margraviate of Hohenzollern. The cathedral, in which the Bishop resides, is Freiburg Minster. Also part of the ecclesiastical province of Freiburg are the suffragan dioceses of Mainz and Rottenburg-Stuttgart. Until 1929 the dioceses of Limburg and Fulda also belonged to this ecclesiastical province. The Archbishop of Freiburg holds the title of metropolitan and the German headquarters of the Caritas International is in Freiburg.

Saint George (the flag of Freiburg has the cross of George), Lambert of Maastricht and the catacomb saint, Alexander, are the patron saints of Freiburg. Many works of art depicting these saints are in the Freiburg Minster, on the Minster square, just as in the museums and archives of the city, including some by Hans Baldung Grien, Hans Holbein the Younger and Gregorius Sickinger.

In 1805, with the attack of Breisgau on the Grand Duchy of Baden by a Catholic ruler, many Protestants moved into the city. Since 2007, any Protestants who are not part of a ‘free church’ belong to the newly founded deanery of Freiburg as part of the parish of Südbaden which in itself is a part of the Landeskirche Baden.

The seat of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Baden, a free Lutheran church, is situated in Freiburg. There are multiple other free Protestant churches: e.g. the Calvary Chapel or Chrischona International. An old congregation has existed in Freiburg since the late 1900s, which utilizes the old monastery church of the Ursulines in the black monastery at the border of the old city center. The Catholic Church of St. Maria Schutz has been made available for Masses by Greek, Serbian, Russian and Rumanian Orthodox congregations.

Judaism

Jews are said to have lived in the city before 1230, but it was only after 1230 that they supposedly founded an official community in the Webergasse (a small street within the city center). The counts of Freiburg bought the lucrative Schutzjude, which means that all personal information on Jews living in Freiburg was directly sent to Konrad II and his co-reigning son Friedrich. The two issued a comprising letter promising safety and liberty to all local Jews on 12 October 1338. It lost all value shortly after, however, on 1 January 1349. Even though the plague had not yet broken out in the city, Jews were accused of having spread it and taken into custody. All Jewish people with the exception of pregnant women were burned alive on 31 January 1349. The remaining children were forced to be baptized. This pogrom left Jews very hesitant to settle in the city again. In 1401 the city council decreed a regulation to ban all Jews from Freiburg (orig. Middle High German dialect: “daz dekein Jude ze Friburg niemmerme sin sol”[27]. This was also officially reaffirmed by King Sigismund with a ban for life (orig. German: “Ewige Vertreibung”) in 1424. It was only in 1809 that Jews were once again allowed permanent residence within the city. They subsequently founded a Jewish community in 1836.

At the Kristallnacht in 1938, the synagogue, built in 1870, was set afire. Numerous shops and apartments of Jewish citizens of Freiburg were devastated and plundered by National Socialists without the intervention of police or fire department. Male, wealthy, Jewish citizens were kidnapped and taken to concentration camps (in Buchenwald and Dachau) where they were subjected to forced labor or executed and their money and property stolen. On October 22, 1940 the remaining Jews of Baden and Pfalz were deported to Camp de Gurs in southern France. One among many collecting points was Annaplatz. So-called 'Stolpersteine', tiles with names and dates on them, commemorate the victims of the prosecution of Jews during the Nazi-Era in the city's cobble. Journalist Käthe Vordtriede of the Volkswacht even received two Stolpersteine to commemorate her life. The first one was inserted into the ground in front of the Vordtriede-Haus Freiburg in 2006 and the second one in front of the Basler Hof, the regional authorities, in spring 2013. This was also the seat of the Gestapo until 1941, where unrelenting people were cruelly interrogated, held prisoner or at worst deported. The only solutions were flight or emigration. The Vordtriede family, however, was lucky and escaped in time.

Transport

Freiburg has an extensive pedestrian zone in the city centre where no motor cars are allowed. Freiburg also has an excellent public transport system, operated by the city-owned VAG Freiburg. The backbone of the system is the Freiburg tramway network, supplemented by feeder buses. The tram network is very popular as the low fares allow for unlimited transport in the city and surrounding area. Furthermore, any ticket for a concert sports or other event is also valid for use on public transport. The tram network is so vast that 70% of the population live within 500m of a tram stop with a tram every 8 mins.

Freiburg is on the main Frankfurt am Main – Basel railway line, with frequent and fast long-distance passenger services from the Freiburg Hauptbahnhof to major German and other European cities. Other railway lines run east into the Black Forest and west to Breisach and are served by the Breisgau S-Bahn. The line to Breisach is the remaining stub of the Freiburg–Colmar international railway, severed in 1945 when the railway bridge over the Rhine at Breisach was destroyed, and was never replaced.

The city also is served by the A5 Frankfurt am Main – Basel motorway.

Freiburg is served by EuroAirport Basel-Mulhouse-Freiburg in France, close to the borders of both Germany and Switzerland, 70 km (43 mi) south of Freiburg. Karlsruhe/Baden-Baden airport (Baden Airpark) is approximately 100 km (62 mi) north of Freiburg and is also served by several airlines. The nearest larger international airports include Stuttgart (200 km (120 mi)), Frankfurt/Main (260 km (160 mi)), and Munich (430 km (270 mi)). The nearby Flugplatz Freiburg, a small airfield in the Messe, Freiburg district, lacks commercial service but is used for private aviation.

Car share websites such as BlaBlaCar are commonly used among Freiburg residents, since they are considered relatively safe.

The investment in transport has resulted in a large increase in both cycle, pedestrian and public transport usage with projections of car journeys accounting for 29% of journey times.

Sports

Freiburg is home to football teams SC Freiburg, which plays at the Schwarzwald-Stadion and is represented in the 1. or 2. Bundesliga since 1978, and Freiburger FC, German championship winner of 1907. In 2016, SC Freiburg got promoted to the highest league for the fifth time in its club history. The club became generally known in Germany for its steady staffing policy. Achim Stocker was president of the club from 1972 until his death in 2009. Longtime coach was Volker Finke (1991-2007), to whose initiative the football school of the club goes back. In 2004, SC Freiburg celebrated its 100th anniversary. Since December 2011, the coach is Christian Streich. The women's team of SC Freiburg plays in the first Women's Bundesliga.

Freiburg also has the EHC Freiburg ice hockey team, which plays at the Franz-Siegel Halle. In the season 2003/2004 the EHC Freiburg (the wolves) played in the DEL, the highest German ice hockey league. Currently, season 2018/19, they play in the second league (DEL2).

Additionally, there is the RC Freiburg Rugby union team, which competes in the second Bundesliga South (Baden Wurttemberg). The home ground of the club, the only rugby sports field in the wider area, is located in March-Hugstetten.

Then, there is the volleyball men's team of the FT 1844 Freiburg, which plays in the second Bundesliga since 2001 and the handball women's team of the HSG Freiburg, which plays in the 3rd Women's Handball League.

Freiburg is represented in the first women's basketball league by the Eisvögel (Kingfisher) USC Freiburg. In the season 2005/2006, the Kingfishers took second place after the end of the second round, in the season 2006/2007 it was the fourth place. The men's team of the USC played in the 2009/10 season in the ProA (2nd Bundesliga). The Freiburg men's team played their last first-division season in 1998/1999. Currently, season 2018/19, the men's team plays in the Oberliga and the women's team in the regional league.

From 1925 to 1984, the Schauinsland Races took place on an old logging track. The course is still used periodically for European Hill Climb Championships.

Press

Badische Zeitung is the main local daily paper, covering the Black Forest region.

International relations

Twin towns, sister cities

Freiburg is twinned with:

Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad's controversial comments, which included questioning the dimension of the Holocaust, have sparked discussions concerning Freiburg's relationship with Isfahan. Immediately following the comments, Freiburg mayor Salomon postponed a trip to Isfahan, but most people involved, especially those in the Alliance '90/The Greens party, were opposed to cancelling the relationship.[20]

Symbols

The city's coat of arms is Argent a cross Gules, the St George's Cross. Saint George is the city's patron saint. The cross also appears on the city's flag, which dates from about 1368, and is identical to that of England, which has the same patron.

The city also has a seal that can be seen in a few places in the inner city. It is a stylized depiction of the façade of the Wasserschlössle, a castle-like waterworks facility built into a hill that overlooks the residential district of Wiehre. The seal depicts a three-towered red castle on a white background, with green-clad trumpeters atop the two outer towers. Beneath the castle is a gold fleur-de-lis.

Notable residents

_cropped.jpg)

Pre-18th century

- Berthold Schwarz, (c. 1310–1388) fabled alchemist who introduced gunpowder to Germany[21]

- Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam, (1466–1536), Dutch Renaissance humanist and theologian[22]

- Martin Waldseemüller, (c.1470–1520) Renaissance cartographer[23]

18th century

- Aloysius Bellecius (1704–1757), Jesuit ascetic author[24]

- Jean-Henri Naderman (1734–1799) leading harp-maker and a music publisher.

- Johann Nepomuk Locherer, (1773–1837), Roman Catholic priest, theologian and professor.

- Karl von Rotteck, (1775–1840), political activist, historian, politician and political scientist[25]

- Heinrich Schreiber (1793–1872) Catholic theologian and historian, wrote about Freiburg.

- Joseph von Auffenberg, (1798–1857), playwright and poet[26]

19th century

- Bernhard Sigmund Schultze, (1827–1919) obstetrician and gynecologist

- August Weismann, (1834–1914) evolutionary biologist

- Max von Gallwitz, (1852–1937) general and politician

- Adolf Furtwangler (1853–1907) archaeologist, teacher, art historian and museum director.[27]

- Edmund Husserl, (1859–1938) philosopher who established the school of phenomenology

- Max Weber, (1864–1920), lawyer, political economist, and sociologist

- Barney Dreyfuss, (1865–1932), baseball entrepreneur, co-founder of the Major League Baseball world series

- Carl Christian Mez, (1866–1944), botanist

- Friedrich Gempp, (1873–1947) Major General and the founder and first director of the Department Defence of Reichswehr

- Alfred Döblin, (1878–1957), physician and novelist

- Joseph Wirth, (1879–1956), politician (center), member of the Reichstag, chancellor, foreign minister, minister of the interior

- Hans Jantzen, (1881–1967) art historian, specialized in Medieval art.

- Hermann Staudinger, (1881–1965) Nobel Prize laureate in chemistry "for discoveries about macromolecular chemistry"

- Otto Heinrich Warburg, (1883–1970), recipient in 1931 of Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

- Martin Heidegger, (1889–1976) philosopher

- Arnold Fanck (1889–1974) film director and pioneer of the mountain film genre[28]

- Walter Eucken, (1891–1950) economist of the Freiburg school and father of ordoliberalism

- Edith Stein, (1891–1942), nun, Saint of the Catholic Church, martyred by the Nazis, Freiburg university faculty member

- Hans F. K. Günther, (1891–1968) Nazi eugenicist

- Walter Benjamin, (1892–1940), literary critic and philosopher

- Felix H. Man (1893–1985) photographer, art collector and pioneer photojournalist for Picture Post

- Sepp Allgeier (1895–1968) cinematographer, worked with Leni Riefenstahl

- Engelbert Zaschka, (1895–1955) inventor and one of the first German helicopter pioneers

- Kurt Bauch, (1897–1975), art historian

- Friedrich von Hayek, CH FBA (1899–1992), economist, philosopher, Nobel Prize laureate in economics

_(cropped).jpg)

20th century

- Waldemar Hoven (1903–1948), Nazi physician executed for war crimes

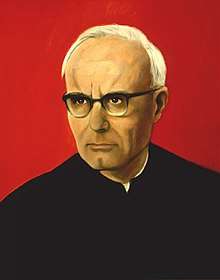

- Karl Rahner SJ (1904–1984), Jesuit priest and influential Roman Catholic theologian

- Hanns Ludin (1905–1947), Nazi diplomat executed for war crimes

- Herbert Niebling (1905–1966), master designer of lace knitting

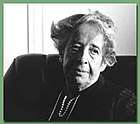

- Hannah Arendt (1906–1975), political theorist

- Hans Bender (1907–1991) lecturer on parapsychology

- Jürgen Aschoff (1913–1998) physician, biologist and behavioral physiologist, co-founded chronobiology

- Bernhard Witkop (1917–2010) organic chemist

- Hoimar von Ditfurth (1921–1989), physician

- Walter Kaufmann, (1921–1980) philosopher, translator and poet.

- Svetlana Geier (1923–2010) translator

- Wolfram Aichele, (1924–2016), artist

- Hedy Epstein (1924–2016), Holocaust refugee and political activist

- Klaus Tschira (1940–2015), entrepreneur

- Wolfgang Schäuble (born 1942), CDU politician, President of the Bundestag since 2017

- Jürgen E. Schrempp (born 1944) former head of DaimlerChrysler

- Michael Leuschner (born 1948) classical pianist and professor of piano at the Hochschule für Musik Freiburg

- Nikolaus Brender (born 1949), journalist

- Borwin, Duke of Mecklenburg (born 1956) head of the House of Mecklenburg

- Peter W. Heller (born 1957) former Deputy Mayor of Freiburg, environmental scientist and venture philanthropist

- Thomas Hengelbrock (born 1958) violinist, musicologist and conductor; co-founded the Freiburger Barockorchester

- Andreas Holschneider (1931–2019), music historian

- Christoph von Marschall (born in 1959) journalist

- Joachim Löw (born 1960), coach of the German national football team since 2006

- Dieter Salomon (born 1960) Alliance '90/The Greens politician, Mayor of Freiburg until 2018

- Johannes Boesiger (born 1962) scriptwriter and producer[29]

- Stephan Burger (born 1962) Roman Catholic clergyman, Archbishop of Freiburg since 2014

- Miriam Gebhardt (born 1962) historian and writer.

- Til Schweiger (born 1963) actor and director[30]

- Christian Meyer (born 1969) track cyclist and gold medallist at the 1992 Summer Olympics

- Boris Kodjoe (born 1973) U.S.based model and actor[31]

- Alexander Bonde (born 1975) in the Bundestag for Alliance '90/The Greens 2002 to 2011

- Joana Zimmer (born 1979), blind pop singer[32]

- Dany Heatley (born 1981) former professional ice hockey winger

- Andreas Lutz (born 1981), media artist analyzes perception versus reality

- Georg Gädker (born 1981), operatic baritone

- Destruction (formed 1982) a thrash metal band

- Benjamin Lebert (born 1982), author and newspaper columnist[33]

- Heinrich Haussler (born 1984) professional cyclist Cervelo TestTeam

- Marie-Laurence Jungfleisch (born 1990) high-jump athlete

Gallery

Inside the belfry of Freiburg Minster

Inside the belfry of Freiburg Minster Landscape from the Schlossberg Tower

Landscape from the Schlossberg Tower

The Schwabentor

The Schwabentor Historic Merchants Hall at the Münsterplatz

Historic Merchants Hall at the Münsterplatz

- The concert hall

- Stadttheater

View of Freiburg

View of Freiburg Freiburg 1944

Freiburg 1944

Fish Fountain

Fish Fountain Main cemetery Freiburg

Main cemetery Freiburg

- Vauban, Freiburg a sustainable model district

References

- "Bevölkerung nach Nationalität und Geschlecht am 31. Dezember 2018". Statistisches Landesamt Baden-Württemberg (in German). July 2019.

- "Metropolitan areas". stats.oecd.org. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Website for the German Agricultural Society: Baden (accessed on January 1, 2008)."Archived copy". Archived from the original on 30 October 2007. Retrieved 1 January 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Temperature extremes

- "Stadt Freiburg im Breisgau: History". www.freiburg.de (Stadt Freiburg im Breisgau). Archived from the original on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 11 April 2009., also Arnold, Benjamin German Knighthood 1050–1300 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985) p. 123.

- "borough". American Heritage Dictionary. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- Link

- Spector, Shmuel and Wigoder, Geoffrey, The Encyclopedia of Jewish life Before and During the Holocaust, New York University Press 2001. See Die Synagoge in Freiburg im Breisgau.

- Robinson, Derek (2005). Invasion 1940. London: Constable & Robinson. pp. 31–32. ISBN 1-84529-151-4.

- "Erlebniswelt Schlossberg" [Experience Schlossberg] (in German). Stadt Freiburg. Archived from the original on 5 April 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- "Freiburg/Breisgau historic weather averages" (in German). weatheronline.de. Retrieved 22 June 2014.

- "Freiburg/Breisgau historic extremes" (in French). Meteociel.fr. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- , (City of Freiburg im Breisgau)

- Andrew Purvis. "Freiburg, Germany: is this the greenest city in the world?". the Guardian. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- "OB-Wahl Freiburg 2018 – Martin Horn – Kandidat". OB-Wahl Freiburg 2018 (in German). Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- "Auf Wahlparty: Freiburgs neuer Oberbürgermeister Horn attackiert". Spiegel Online. 6 May 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- "City Mayors: About City Mayors". Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- "European Union". Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- "Lawyer Freiburg". Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 10 March 2007. Retrieved 19 December 2005.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

-

-

-

-

-

- . Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 11 (11th ed.). 1911.

- IMDb Database retrieved 27 August 2018

- IMDb Database retrieved 27 August 2018

- IMDb Database retrieved 27 August 2018

- IMDb Database retrieved 27 August 2018

- IMDb Database retrieved 27 August 2018

- IMDb Database retrieved 27 August 2018

Further reading

- Käflein, Achim (photographs); Huber, Alexander (German text) (2008). Trefzer-Käflein, Annette (ed.). Freiburg. Freund, BethAnne (English translation). Freiburg: edition-kaeflein.de. ISBN 978-3-940788-01-6. OCLC 301982091.

- The Freiburg Charter for Sustainable Urbanism – a collaboration between the City of Freiburg and The Academy of Urbanism

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Freiburg. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Freiburg im Breisgau. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Freiburg. |

- Official website

- Freiburg Breisgau digital city tour

- Freiburg Breisgau Tourism & History & Pictures

- Freiburg City Panoramas – Panoramic views and virtual tours

- City of Freiburg

- Augustinermuseum

- Freiburg University of Education

- VAG Freiburg Freiburg Public Transit Authority

- Freiburg-Home.com – Information & Reviews about Freiburg

- Webcams in Freiburg and the Black Forest

- Tramway in Freiburg

- fudder – a popular online magazine about Freiburg (Winner of Grimme Online Award 2007)

- Freiburg's History for Pedestrians

- Freiburg - Green City

- Hotels in Freiburg

- BUND (Friends of the Earth Germany): Freiburg & Environment: Ecological Capital – Environmental Capital – Solar City - Sustainable City - Green City?

- Freiburg Excursion Destinations and Film Recommendations

.jpg)