Defensive wall

A defensive wall is a fortification usually used to protect a city, town or other settlement from potential aggressors. The walls can range from simple palisades or earthworks to extensive military fortifications with towers, bastions and gates for access to the city.[1] From ancient to modern times, they were used to enclose settlements. Generally, these are referred to as city walls or town walls, although there were also walls, such as the Great Wall of China, Walls of Benin, Hadrian's Wall, Anastasian Wall, and the Atlantic Wall, which extended far beyond the borders of a city and were used to enclose regions or mark territorial boundaries. In mountainous terrain, defensive walls such as letzis were used in combination with castles to seal valleys from potential attack. Beyond their defensive utility, many walls also had important symbolic functions – representing the status and independence of the communities they embraced.

Existing ancient walls are almost always masonry structures, although brick and timber-built variants are also known. Depending on the topography of the area surrounding the city or the settlement the wall is intended to protect, elements of the terrain such as rivers or coastlines may be incorporated in order to make the wall more effective.

Walls may only be crossed by entering the appropriate city gate and are often supplemented with towers. The practice of building these massive walls, though having its origins in prehistory, was refined during the rise of city-states, and energetic wall-building continued into the medieval period and beyond in certain parts of Europe.

Simpler defensive walls of earth or stone, thrown up around hillforts, ringworks, early castles and the like, tend to be referred to as ramparts or banks.

History

From very early history to modern times, walls have been a near necessity for every city. Uruk in ancient Sumer (Mesopotamia) is one of the world's oldest known walled cities. Before that, the proto-city of Jericho in the West Bank had a wall surrounding it as early as the 8th millennium BC. The earliest known town wall in Europe is of Solnitsata, built in the 6th or 5th millennium BC.

The Assyrians deployed large labour forces to build new palaces, temples and defensive walls.[2]

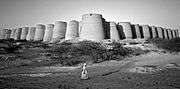

Some settlements in the Indus Valley Civilization were also fortified. By about 3500 BC, hundreds of small farming villages dotted the Indus floodplain. Many of these settlements had fortifications and planned streets. The stone and mud brick houses of Kot Diji were clustered behind massive stone flood dykes and defensive walls, for neighboring communities quarreled constantly about the control of prime agricultural land.[3] Mundigak (c. 2500 BC) in present-day south-east Afghanistan has defensive walls and square bastions of sun dried bricks.[4]

Babylon was one of the most famous cities of the ancient world, especially as a result of the building program of Nebuchadnezzar, who expanded the walls and built the Ishtar Gate.

Exceptions were few, but neither ancient Sparta nor ancient Rome had walls for a long time, choosing to rely on their militaries for defense instead. Initially, these fortifications were simple constructions of wood and earth, which were later replaced by mixed constructions of stones piled on top of each other without mortar.

In Central Europe, the Celts built large fortified settlements which the Romans called oppida, whose walls seem partially influenced by those built in the Mediterranean. The fortifications were continuously expanded and improved.

In ancient Greece, large stone walls had been built in Mycenaean Greece, such as the ancient site of Mycenae (famous for the huge stone blocks of its 'cyclopean' walls). In classical era Greece, the city of Athens built a long set of parallel stone walls called the Long Walls that reached their guarded seaport at Piraeus.

Large rammed earth walls were built in ancient China since the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600–1050 BC), as the capital at ancient Ao had enormous walls built in this fashion (see siege for more info). Although stone walls were built in China during the Warring States (481–221 BC), mass conversion to stone architecture did not begin in earnest until the Tang Dynasty (618–907 AD). Sections of the Great Wall had been built prior to the Qin Dynasty (221–207 BC) and subsequently connected and fortified during the Qin dynasty, although its present form was mostly an engineering feat and remodeling of the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644 AD). The large walls of Pingyao serve as one example. Likewise, the walls of the Forbidden City in Beijing were established in the early 15th century by the Yongle Emperor.

The Romans fortified their cities with massive, mortar-bound stone walls. Among these are the largely extant Aurelian Walls of Rome and the Theodosian Walls of Constantinople, together with partial remains elsewhere. These are mostly city gates, like the Porta Nigra in Trier or Newport Arch in Lincoln.

The Persians built defensive walls to protect their territories, notably the Derbent Wall and the Great Wall of Gorgan built on the either sides of the Caspian Sea against nomadic nations.

Apart from these, the early Middle Ages also saw the creation of some towns built around castles. These cities were only rarely protected by simple stone walls and more usually by a combination of both walls and ditches. From the 12th century AD hundreds of settlements of all sizes were founded all across Europe, which very often obtained the right of fortification soon afterwards.

The founding of urban centers was an important means of territorial expansion and many cities, especially in central and eastern Europe, were founded for this purpose during the period of Eastern settlement. These cities are easy to recognise due to their regular layout and large market spaces. The fortifications of these settlements were continuously improved to reflect the current level of military development.

During the Renaissance era, the Venetians raised great walls around cities threatened by the Ottoman Empire. Examples include the walled cities of Nicosia and Famagusta in Cyprus and the fortifications of Candia and Chania in Crete, which still stand.

- The Walls of Constantinople, a UNESCO World Heritage Site

The gate of the Gonio castle

The gate of the Gonio castle- Wall of Hittite Capital Hattusa (reconstruction)

9th century BC relief of an Assyrian attack on a walled town

9th century BC relief of an Assyrian attack on a walled town

Derbent Walls, late Sassanian period

Derbent Walls, late Sassanian period

The walls of Tallinn, Estonia, a UNESCO World Heritage Site

The walls of Tallinn, Estonia, a UNESCO World Heritage Site

- Defensive wall in Rothenburg ob der Tauber, Germany

- Part of the wall in San Francisco de Campeche, a UNESCO World Heritage Site

A defensive wall in Taroudannt, Morocco

A defensive wall in Taroudannt, Morocco The medieval fortress overlooking the city of Ohrid in North Macedonia

The medieval fortress overlooking the city of Ohrid in North Macedonia

Chinese and Korean troops assaulting the Japanese forces of Hideyoshi in the Siege of Ulsan Castle during the Imjin War (1592–1598)

Chinese and Korean troops assaulting the Japanese forces of Hideyoshi in the Siege of Ulsan Castle during the Imjin War (1592–1598).jpg) Model of the Lines of Communication built around London in 1642–43

Model of the Lines of Communication built around London in 1642–43

A defensive wall located in City of San Marino, San Marino

A defensive wall located in City of San Marino, San Marino Defensive walls around the ancient Egyptian settlement of Buhen

Defensive walls around the ancient Egyptian settlement of Buhen A coastal defensive wall of Ulcinj Castle, Montenegro

A coastal defensive wall of Ulcinj Castle, Montenegro Walls of the Ark of Bukhara

Walls of the Ark of Bukhara Greek walls in Gela, Sicily

Greek walls in Gela, Sicily Porte St. Louis, part of Ramparts of Quebec City, the only remaining fortified city walls in North America north of Mexico

Porte St. Louis, part of Ramparts of Quebec City, the only remaining fortified city walls in North America north of Mexico The remains of the boom towers on either side of the River Wensum at Norwich

The remains of the boom towers on either side of the River Wensum at Norwich Garrison Border Town of Elvas and its Fortifications, the largest bulwarked dry ditch system in the world and an UNESCO World Heritage Site, Portugal

Garrison Border Town of Elvas and its Fortifications, the largest bulwarked dry ditch system in the world and an UNESCO World Heritage Site, Portugal The city walls of Jaisalmer, India, also known as Jaisalmer Fort due to its size and complexity in comparison to other city walls. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and is considered one of the largest and best preserved city walls, along with its Medieval Indian town, where many of the stone-carved buildings have not changed since the 12th century.

The city walls of Jaisalmer, India, also known as Jaisalmer Fort due to its size and complexity in comparison to other city walls. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and is considered one of the largest and best preserved city walls, along with its Medieval Indian town, where many of the stone-carved buildings have not changed since the 12th century.

Composition

At its simplest, a defensive wall consists of a wall enclosure and its gates. For the most part, the top of the walls were accessible, with the outside of the walls having tall parapets with embrasures or merlons. North of the Alps, this passageway at the top of the walls occasionally had a roof.

In addition to this, many different enhancements were made over the course of the centuries:

- City ditch: a ditch dug in front of the walls, occasionally filled with water.

- Gate tower: a tower built next to, or on top of the city gates to better defend the city gates.

- Wall tower: a tower built on top of a segment of the wall, which usually extended outwards slightly, so as to be able to observe the exterior of the walls on either side. In addition to arrow slits, ballistae, catapults and cannons could be mounted on top for extra defence.

- Pre-wall: wall built outside the wall proper, usually of lesser height – the space in between was usually further subdivided by additional walls.

- Additional obstacles in front of the walls.

The defensive towers of west and south European fortifications in the Middle Ages were often very regularly and uniformly constructed (cf. Ávila, Provins), whereas Central European city walls tend to show a variety of different styles. In these cases the gate and wall towers often reach up to considerable heights, and gates equipped with two towers on either side are much rarer. Apart from having a purely military and defensive purpose, towers also played a representative and artistic role in the conception of a fortified complex. The architecture of the city thus competed with that of the castle of the noblemen and city walls were often a manifestation of the pride of a particular city.

Urban areas outside the city walls, so-called Vorstädte, were often enclosed by their own set of walls and integrated into the defense of the city. These areas were often inhabited by the poorer population and held the "noxious trades". In many cities, a new wall was built once the city had grown outside of the old wall. This can often still be seen in the layout of the city, for example in Nördlingen, and sometimes even a few of the old gate towers are preserved, such as the white tower in Nuremberg. Additional constructions prevented the circumvention of the city, through which many important trade routes passed, thus ensuring that tolls were paid when the caravans passed through the city gates, and that the local market was visited by the trade caravans. Furthermore, additional signaling and observation towers were frequently built outside the city, and were sometimes fortified in a castle-like fashion. The border of the area of influence of the city was often partially or fully defended by elaborate ditches, walls and hedges. The crossing points were usually guarded by gates or gate houses. These defenses were regularly checked by riders, who often also served as the gate keepers. Long stretches of these defenses can still be seen to this day, and even some gates are still intact. To further protect their territory, rich cities also established castles in their area of influence. An example of this practice is the Romanian Bran Castle, which was intended to protect nearby Kronstadt (today's Braşov).

The city walls were often connected to the fortifications of hill castles via additional walls. Thus the defenses were made up of city and castle fortifications taken together. Several examples of this are preserved, for example in Germany Hirschhorn on the Neckar, Königsberg and Pappenheim, Franken, Burghausen in Oberbayern and many more. A few castles were more directly incorporated into the defensive strategy of the city (e.g. Nuremberg, Zons, Carcassonne), or the cities were directly outside the castle as a sort of "pre-castle" (Coucy-le-Chateau, Conwy and others). Larger cities often had multiple stewards – for example Augsburg was divided into a Reichstadt and a clerical city. These different parts were often separated by their own fortifications.

With the development of firearms came the necessity to expand the existing installation, which occurred in multiples stages. Firstly, additional, half-circular towers were added in the interstices between the walls and pre-walls in which a handful of cannons could be placed. Soon after, reinforcing structures – or "bastions" – were added in strategically relevant positions, such as at the gates or corners. A well-preserved example of this is the Spitalbastei in Rothenburg or the bastions built as part of the 17th-century walls surrounding Derry, a city in Northern Ireland; however, at this stage the cities were still only protected by relatively thin walls which could offer little resistance to the cannons of the time. Therefore, new, star forts with numerous cannons and thick earth walls reinforced by stone were built. These could resist cannon fire for prolonged periods of time. However, these massive fortifications severely limited the growth of the cities, as it was much more difficult to move them as compared to the simple walls previously employed – to make matters worse, it was forbidden to build "outside the city gates" for strategic reasons and the cities became more and more densely populated as a result.

Decline

In the wake of city growth and the ensuing change of defensive strategy, focusing more on the defense of forts around cities, many city walls were demolished. Also, the invention of gunpowder rendered walls less effective, as siege cannons could then be used to blast through walls, allowing armies to simply march through. Today, the presence of former city fortifications can often only be deduced from the presence of ditches, ring roads or parks.

Furthermore, some street names hint at the presence of fortifications in times past, for example when words such as "wall" or "glacis" occur. Wall Street in New York City, itself a metonym for the entire United States financial system, is one example.

In the 19th century, less emphasis was placed on preserving the fortifications for the sake of their architectural or historical value – on the one hand, complete fortifications were restored (Carcassonne), on the other hand many structures were demolished in an effort to modernize the cities. One exception to this is the "monument preservation" law by the Bavarian King Ludwig I of Bavaria, which led to the nearly complete preservation of many monuments such as the Rothenburg ob der Tauber, Nördlingen and Dinkelsbühl. The countless small fortified towns in the Franconia region were also preserved as a consequence of this edict.

Modern era

Walls and fortified wall structures were still built in the modern era. They did not, however, have the original purpose of being a structure able to resist a prolonged siege or bombardment. Modern examples of defensive walls include:

- Berlin's city wall from the 1730s to the 1860s was partially made of wood. Its primary purpose was to enable the city to impose tolls on goods and, secondarily, also served to prevent the desertion of soldiers from the garrison in Berlin.

- The Berlin Wall (1961 to 1989) did not exclusively serve the purpose of protection of an enclosed settlement. One of its purposes was to prevent the crossing of the Berlin border between the German Democratic Republic and the West German exclave of west-Berlin.

- The Nicosia Wall along the Green Line divides North and South Cyprus.

- In the 20th century and after, many enclaves Jewish settlements in Israel were and are surrounded by fortified walls

- Mexico–United States barrier, a wall advocated by U.S. President Donald Trump for the Mexico–United States border to prevent illegal immigration, drug smuggling, human trafficking, and entry of potential terrorists[5]

- Belfast, Northern Ireland by the "peace lines".

Additionally, in some countries, different embassies may be grouped together in a single "embassy district," enclosed by a fortified complex with walls and towers – this usually occurs in regions where the embassies run a high risk of being target of attacks. An early example of such a compound was the Legation Quarter in Beijing in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Most of these modern city walls are made of steel and concrete. Vertical concrete plates are put together so as to allow the least space in between them, and are rooted firmly in the ground. The top of the wall is often protruding and beset with barbed wire in order to make climbing them more difficult. These walls are usually built in straight lines and covered by watchtowers at the corners. Double walls with an interstitial "zone of fire", as had the former Berlin Wall, are now rare.

In September 2014, Ukraine announced the construction of the "European Rampart" alongside its border with Russia to be able to successfully apply for a visa-free movement with the European Union.[6]

A view of the Berlin Wall in 1986

A view of the Berlin Wall in 1986

The fortified wall of a police station in Belfast, Northern Ireland

The fortified wall of a police station in Belfast, Northern Ireland

Dimensions of famous city walls

| Wall | Max width (m) | Minimum width (m) | Max Height (m) | Lowest Height (m) | Length (km) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aurelian Walls | 3.5 | 16 | 8 | 19 | |

| Ávila | 3 | 12 | 2.5 | ||

| Baghdad | 45 | 12 | 30 | 18 | 7 |

| Beijing (inner) | 20 | 12 | 15 | 24 | |

| Beijing (outer) | 15 | 4.5 | 7 | 6 | 28 |

| Carcassonne | 3 | 8 | 6 | 3 | |

| Chang'an | 16 | 12 | 12 | 26 | |

| Dubrovnik | 6 | 1.5 | 25 | 1.9 | |

| Forbidden City | 8.6 | 6.6 | 8 | ||

| Harar | 5 | 3.5 | |||

| Itchan Kala | 6 | 5 | 10 | 2 | |

| Jerusalem | 2.5 | 12 | 4 | ||

| Khanbaliq | 10.6 | ||||

| Linzi | 42 | 26 | |||

| Luoyang | 25 | 11 | 12 | ||

| Marrakech | 2 | 9 | 20 | ||

| Nanjing | 19.75 | 7 | 26 | 25.1 | |

| Nicaea | 3.7 | 9 | 5 | ||

| Pingyao | 12 | 3 | 10 | 8 | 6 |

| Servian Wall | 4 | 3.6 | 10 | 6 | 11 |

| Suzhou | 11 | 5 | 7 | ||

| Theodosian Walls (inner) | 5.25 | 12 | 6 | ||

| Theodosian Walls (outer) | 2 | 9 | 8.5 | 6 | |

| Vatican | 2.5 | 8 | 3 | ||

| Xi'an | 18 | 12 | 12 | 14 | |

| Xiangyang | 10.8 | 7.3 | |||

| Zhongdu | 12 | 24 |

Seoul (Hanyang doseong) Hwaseong (Suwon city)

See also

Notes

- Caves, R. W. (2004). Encyclopedia of the City. Routledge. p. 756. ISBN 978-0415862875.

- Banister Fletcher's A History of Architecture By Banister Fletcher, Sir, Dan Cruickshank, Dan Cruickhank, Sir Banister Fletcher. Published 1996 Architectural Press. Architecture. 1696 pages. ISBN 0-7506-2267-9. p. 20.

- The Encyclopedia of World History: ancient, medieval, and modern, chronologically arranged By Peter N. Stearns, William Leonard Langer. Compiled by William L Langer. Published 2001 Houghton Mifflin Books. History / General History. ISBN 0-395-65237-5. p. 17.

- Banister Fletcher's A History of Architecture By Banister Fletcher, Sir, Dan Cruickshank, Dan Cruickhank, Sir Banister Fletcher. Published 1996 Architectural Press. Architecture. 1696 pages. ISBN 0-7506-2267-9. p. 100.

- "Trump Orders Mexican Border Wall to Be Built and Plans to Block Syrian Refugees". New York Times.

- "Yatseniuk: Project Wall to allow Ukraine to get visa-free regime with EU". Interfax-Ukraine.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Defensive walls. |

- Monika Porsche: Stadtmauer und Stadtentstehung – Untersuchungen zur frühen Stadtbefestigung im mittelalterlichen Deutschen Reich. - Hertingen, 2000. ISBN 3-930327-07-4.