Martin Waldseemüller

Martin Waldseemüller (c. 1470 – 16 March 1520) was a German cartographer and humanist scholar. Sometimes known by the Latinized form of his name, Hylacomylus, his work was influential among contemporary cartographers. He and his collaborator, Matthias Ringmann, are credited with the first recorded usage of the word America to name a portion of the New World in honour of the Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci. Waldseemüller was also the first to map South America as a continent separate from Asia; the first to produce a printed globe and the first to create a printed wall map of Europe. A set of his maps printed as an appendix to the 1513 edition of Ptolemy's Geography is considered to be the first example of a modern atlas.

Martin Waldseemüller | |

|---|---|

Martin Waldseemüller (19th-century painting) | |

| Born | c. 1470 |

| Died | 16 March 1520 (aged 49–50) Sankt Didel |

| Alma mater | University of Freiburg |

| Occupation | Cartographer |

| Movement | German Renaissance |

Life and works

Details of Waldseemüller's life are scarce. He was born around 1470 in the German town of Wolfenweiler. His father was a butcher and moved to Freiburg im Breisgau in about 1480. Records show that Waldseemüller was enrolled in 1490 at the University of Freiburg where Gregor Reisch, a noted humanist scholar, was one of his influential teachers.[1][2] After finishing at the university, he lived in Basel where he was ordained a priest and, apparently, gained experience in printing and engraving while working with the printer community in Basel.[3][4]

Around 1500, an association of humanist scholars formed in Saint-Dié under the patronage of René II, Duke of Lorraine. They called themselves the Gymnasium Vosagense and their leader was Walter Lud. Their initial intention was to publish a new edition of Ptolemy's Geography. Waldseemüller was invited to join the group and contribute his skills as a cartographer. It is not clear how he came to the groups's attention, but Lud later described him as a master cartographer. Matthias Ringmann was also brought into the group because of his previous work with the Geography and his knowledge of Greek and Latin. Ringmann and Waldseemüller soon became friends and collaborators.[5][6]

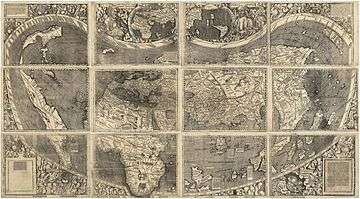

1507 world map

In 1506, the Gymnasium obtained a French translation of the Soderini Letter, a booklet attributed to Amerigo Vespucci that provided a sensational account of four alleged Vespucci voyages to explore the coast of lands recently discovered in the western Atlantic. The Gymnasium surmised that this was the "new world" or the "antipodes" hypothesized by classical writers. The Soderini Letter gave Vespucci credit for discovery of this new continent and implied that newly obtained Portuguese maps were based on his explorations. They decided to put aside the Geography for the moment and publish a brief Introduction to Cosmography with an accompanying world map. The Introduction was written by Ringmann and included a Latin translation of the Soderini Letter. In a preface to the Letter, Ringmann wrote

"I see no reason why anyone could properly disapprove of a name derived from that of Amerigo, the discoverer, a man of sagacious genius. A suitable form would be Amerige, meaning Land of Amerigo, or America, since Europe and Asia have received women's names."[7]

While Ringmann was writing the Introduction, Waldseemüller focused on the creation of a world map using an aggregation of sources including maps based on the works of Ptolemy, Henricus Martellus, Alberto Cantino and Nicolò de Caverio. In addition to a large 12-panel wall map, Waldseemüller created a smaller, simplified globe. The wall map was decorated with prominent portraits of Ptolemy and Vespucci. The map and globe were notable for showing the New World as a continent separate from Asia and for naming the southern landmass America. By April 1507, the map, globe and accompanying book, Introduction to Cosmography, were published. A thousand copies were printed and sold throughout Europe.[8]

The Introduction and map were a great success and four editions were printed in the first year alone. The map was widely used in universities and was influential among cartographers who admired the craftsmanship that went into its creation. In the following years other maps were printed that often incorporated the name America. Although Waldseemüller had intended the name to apply only to a specific part of Brazil, other maps applied it to the entire continent. In 1538, Gerardus Mercator used America to name both the North and South continents on his influential map and by this point the name was securely fixed on the New World[9]

Ptolemy's Geography (1513)

After 1507, Waldseemüller and Ringmann continued to collaborate on a new edition of Ptolemy's Geography. In 1508 Ringmann traveled to Italy and obtained a Greek manuscript of Geography (Codex Vaticanum Graecorum 191). With this key reference they continued to make progress and Waldseemüller was able to finish his maps. However, completion was forestalled when their patron, Duke René II, died in 1508. The new edition was finally printed in 1513 by Johannes Schott in Strasbourg. By then, Waldseemüller had pulled out of the project and was not credited for his cartographic work.[10][11] Nevertheless his maps were recognized as important contributions to the science of cartography and was considered a standard reference work for many decades.[12]

Approximately twenty of Waldseemüller's tabulae modernae (modern maps) were included in the new Geography as a separate appendix, Claudii Ptolemaei Supplementem. This supplement constitutes the first modern atlas.[13] Maps of Lorraine and the upper Rhine region were the first printed maps of those regions and were probably based on survey work done by Waldseemüller himself.[14]

The world map published in the 1513 Geography seems to indicate that Waldseemüller had second thoughts about the name and the nature of the lands discovered in the western Atlantic. The New World was no longer clearly shown as a continent separate from Asia and the name America had been replaced with Terra Incognita (Unknown Land). What caused him to make these changes is not clear but perhaps he was influenced by contemporary criticism that Vespucci had usurped Columbus's primacy of discovery.[15]

Other works

Waldseemüller was also interested in surveying and surveying instruments. In 1508 he contributed a treatise on surveying and perspective to the fourth edition of Gregor Reisch’s Margarita Philosophica. He included an illustration of a forerunner to the theodolite, a surveying instrument he called the polimetrum. In 1511 he published the Carta Itineraria Europae, a road map of Europe that showed important trade routes as well as pilgrim routes from central Europe to Santiago de Compostela, Spain. It was the first printed wall map of Europe.[16]

In 1516 he produced another large-scale wall map of the world, the Carta Marina Navigatoria, printed in Strasbourg. It was designed in the style of portolan charts and consisted of twelve printed sheets.

The Paris Green Globe (or Globe vert), has been attributed to Waldseemüller by experts at the Bibliotheque Nationale. However, the attribution is not universally accepted.

Waldseemüller died without a will on 16 March 1520 in Saint-Dié, where he had served as a canon in the collegiate Church of Saint-Dié since 1514.[17]

1507 map rediscovered

The 1507 wall map was lost for a long time, but a copy was found in Schloss Wolfegg in southern Germany by Joseph Fischer in 1901. It is the only known copy and was purchased by the United States Library of Congress in May 2003[18] Five copies of Waldseemüller's globular map survive in the form of "gores": printed maps that were intended to be cut out and pasted onto a wooden globe.

See also

- Waldseemüller map

- Naming of America

- Discoverer of the Americas

- Richard Amerike

- History of cartography

- List of Roman Catholic scientist-clerics

- List of German inventors and discoverers

Notes

- Lester p. 343

- Meurer p. 1204

- Lester p. 343

- Fernández-Armesto p. 182

- Lester pp. 343-344

- Baldi p. 101

- Fernandez-Armesto p. 185

- Meurer pp. 1204-1206

- Fernandez-Armesto pp. 185-186

- Lester p. 379

- Meurer p. 1206

- Wolff p. 117

- Wolff p. 116

- Meurer p. 1207

- Meurer p. 1206

- Wolff pp. 117-118

- Van Duzer 2011

- Hébert, John R. (September 2003). "The Map That Named America". Library of Congress. 62 (9). Retrieved 27 October 2018.

References

- David Brown: 16th-Century Mapmaker's Intriguing Knowledge, in: Washington Post, 2008-11-17, p. A7

- Peter W. Dickson: "The Magellan Myth: Reflections on Columbus, Vespucci and the Waldseemueller Map of 1507", Printing Arts Press, 2007, 2009 (Second Edition)

- Fernández-Armesto, Felipe (2007). Amerigo: The Man Who Gave his Name to America. New York: Random House. ISBN 9781400062812.

- Hessler, John W. (2008). The naming of America : Martin Waldseemüller's 1507 world map and the Cosmographiae introductio. GILES. ISBN 978-1904832492.

- Toby Lester: Putting America on the Map, Smithsonian, Volume 40, Number 9, p. 78, December 2009

- Lester, Toby (2009). The Fourth Part of the World: An Astonishing Epic of Global Discovery, Imperial Ambition, and the Birth of America. New York: Free Press. ISBN 9781416535317.

- Meurer, Peter H. (2007). "Cartography in the German Lands, 1450–1650,". In Woodward, David (ed.). The History of Cartography, Volume 3: Cartography in the European Renaissance, Part 2 (PDF). University of Chicago. pp. 1204–1207. ISBN 978-0-226-90734-5.

- Seymour Schwartz: Putting "America" on the Map, the Story of the Most Important Graphic Document in the History of the United States, Prometheus Books, Amherst, New York, 2007

- Van Duzer, Chet; Larger, Benoît (2011). "Martin Waldseemuller's Death Date". Imago Mundi. 63 (2).

- Wolff, Hans (1992). "Martin Waldseemuller". In Wolff, Hans (ed.). America : Early Maps of the New World. Munich: Prestel. pp. 111–126. ISBN 3791312324.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Martin Waldseemüller. |

- The Cosmographiæ Introductio of Martin Waldseemüller (Facsimile), via Google Books.

- Joseph Fischer (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- "16th-Century Mapmaker's Intriguing Knowledge", David Brown, The Washington Post. November 17, 2008; Page A07.

- "You Are Here—The Library of Congress buys 'America's birth certificate'.", John J. Miller, The Wall Street Journal. July 25, 2003.

- "The map that changed the world", Toby Lester The BBC, October 28, 2009.

- "Naming of America", BBC.

- . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

- World Digital Library presentation of Universalis cosmographia secundum Ptholomaei traditionem et Americi Vespucii aliorum que lustrationes or A Map of the Entire World According to the Traditional Method of Ptolemy and Corrected with Other Lands of Amerigo Vespucci. Library of Congress.

- Cosmographiae Introductio: cum Quibusdam Geometriae ac Astronomiae Principiis ad eam rem Necessariis From the Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress

- Cosmographiae introductio: cum quibusdam geometriae ac astronomiae principiis ad eam rem necessariis... From the John Boyd Thacher Collection at the Library of Congress

- Carta Marina of 1516, Speaker: Chet Van Duzer Video from the Library of Congress

- Carta Marina of 1516, digital copy at the Library of Congress