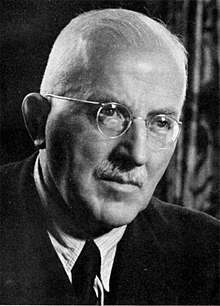

Hermann Staudinger

Hermann Staudinger (23 March 1881 – 8 September 1965) was a German organic chemist who demonstrated the existence of macromolecules, which he characterized as polymers. For this work he received the 1953 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Hermann Staudinger | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 23 March 1881 |

| Died | 8 September 1965 (aged 84) |

| Alma mater | Technische Universität Darmstadt, University of Halle |

| Known for | Polymer chemistry |

| Spouse(s) | Magda Staudinger (née Woit) |

| Awards | Nobel Prize in Chemistry |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Organic and Polymer chemistry |

| Institutions | University of Strasbourg University of Karlsruhe ETH Zürich University of Freiburg |

| Thesis | Anlagerung des Malonesters an ungesättigte Verbindungen (1903) |

| Doctoral advisor | Daniel Vorländer |

| Doctoral students | Werner Kern Tadeusz Reichstein Leopold Ružička Rudolf Signer |

He is also known for his discovery of ketenes and of the Staudinger reaction. Staudinger, together with Leopold Ružička, also elucidated the molecular structures of pyrethrin I and II in the 1920s, enabling the development of pyrethroid insecticides in the 1960s and 1970s.

Early work

Staudinger was born in 1881 in Worms. Staudinger, who initially wanted to become a botanist, studied chemistry at the University of Halle, at the TH Darmstadt and at the LMU Munich. He received his "Verbandsexamen" (comparable to Master's degree) from TH Darmstadt. After receiving his Ph.D. from the University of Halle in 1903, Staudinger qualified as an academic lecturer at the University of Strasbourg in 1907.[1]

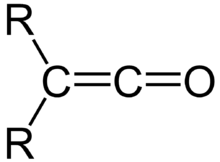

It was here that he discovered the ketenes, a family of molecules characterized by the general form depicted in Figure 1.[2] Ketenes would prove a synthetically important intermediate for the production of yet-to-be-discovered antibiotics such as penicillin and amoxicillin.

In 1907, Staudinger began an assistant professorship at the Technical University of Karlsruhe. Here, he successfully isolated a number of useful organic compounds (including a synthetic coffee flavoring) as more completely reviewed by Rolf Mülhaupt.[3]

The Staudinger reaction

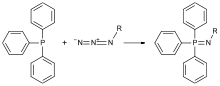

In 1912, Staudinger took on a new position at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, Switzerland. One of his earliest discoveries came in 1919, when he and colleague Meyer reported that azides react with triphenylphosphine to form phosphinimines (Figure 2).[4] This reaction – commonly referred to as the Staudinger reaction – produces a high phosphinimine yield.[5]

Polymer chemistry

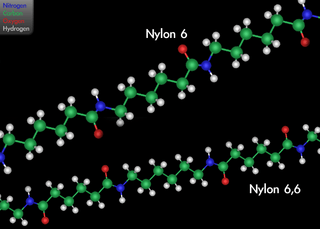

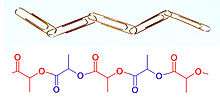

While at Karlsruhe and later, Zurich, Staudinger began research in the chemistry of rubber, for which very high molecular weights had been measured by the physical methods of Raoult and van 't Hoff. Contrary to prevailing ideas (see below), Staudinger proposed in a landmark paper published in 1920 that rubber and other polymers such as starch, cellulose and proteins are long chains of short repeating molecular units linked by covalent bonds.[6] In other words, polymers are like chains of paper clips, made up of small constituent parts linked from end to end (Figure 3).

At the time, leading organic chemists such as Emil Fischer and Heinrich Wieland[3][7] believed that the measured high molecular weights were only apparent values caused by the aggregation of small molecules into colloids. At first, the majority of Staudinger’s colleagues refused to accept the possibility that small molecules could link together covalently to form high-molecular weight compounds. As Mülhaupt aptly notes, this is due in part to the fact that molecular structure and bonding theory were not fully understood in the early 20th century.[3]

In 1926 he was appointed lecturer of chemistry at the University of Freiburg at Freiburg im Breisgau (Germany), where he spent the rest of his career.[8] In 1927, he married the Latvian botanist, Magda Voita (also shown as (German: Magda Woit), who was a collaborator with him until his death and whose contributions he acknowledged in his Nobel Prize acceptance.[9] Further evidence to support his polymer hypothesis emerged in the 1930s. High molecular weights of polymers were confirmed by membrane osmometry, and also by Staudinger’s measurements of viscosity in solution. The X-ray diffraction studies of polymers by Herman Mark provided direct evidence for long chains of repeating molecular units. And the synthetic work led by Carothers demonstrated that polymers such as nylon and polyester could be prepared by well-understood organic reactions. His theory opened up the subject to further development, and helped place polymer science on a sound basis.

Legacy

Staudinger’s groundbreaking elucidation of the nature of the high-molecular weight compounds he termed Makromoleküle paved the way for the birth of the field of polymer chemistry.[10] Staudinger himself saw the potential for this science long before it was fully realized. "It is not improbable," Staudinger commented in 1936, "that sooner or later a way will be discovered to prepare artificial fibers from synthetic high-molecular products, because the strength and elasticity of natural fibers depend exclusively on their macro-molecular structure – i.e., on their long thread-shaped molecules."[11] Staudinger founded the first polymer chemistry journal in 1940,[12] and in 1953 received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for "his discoveries in the field of macromolecular chemistry."[13] In 1999, the American Chemical Society and Gesellschaft Deutscher Chemiker designated Staudinger's work as an International Historic Chemical Landmark.[14] His pioneering research has afforded the world myriad plastics, textiles, and other polymeric materials which make consumer products more affordable, attractive and fun, while helping engineers develop lighter and more durable structures.

See also

- Heidegger and Nazism: denounced or demoted non-Nazis

- Polymer science

Notes

- "Hermann Staudinger - Biographical". Nobelprize.org. 1953. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- Hermann Staudinger (1905). "Ketene, eine neue Körperklasse". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft. 38 (2): 1735–1739. doi:10.1002/cber.19050380283.

- Mülhaupt, R. (2004). "Hermann Staudinger and the Origin of Macromolecular Chemistry". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43 (9): 1054–1063. doi:10.1002/anie.200330070. PMID 14983438.

- Staudinger, H.; Meyer, J. (1919). "Über neue organische Phosphorverbindungen III. Phosphinmethylenderivate und Phosphinimine". Helv. Chim. Acta. 2 (1): 635–646. doi:10.1002/hlca.19190020164.

- Breinbauer, R.; Kohn, M. (2004). "The Staudinger Ligation – A Gift to Chemical Biology". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43 (24): 3106–3116. doi:10.1002/anie.200401744. PMID 15199557.

- Staudinger, H. (1920). "Über Polymerisation". Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 53 (6): 1073–1085. doi:10.1002/cber.19200530627.

- Feldman, S. D.; Tauber, A. I. (1997). "Sickle Cell Anemia: Reexamining the First "Molecular Disease"". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 17 (4): 623–650. doi:10.1353/bhm.1997.0178.

- Biography on Nobel prize website

- Ogilvie & Harvey 2000, p. 1223.

- Staudinger, H. (1933). "Viscosity investigations for the examination of the constitution of natural products of high molecular weight and of rubber and cellulose". Trans. Faraday Soc. 29 (140): 18–32. doi:10.1039/tf9332900018.

- Staudinger, H.; Heuer, W.; Husemann, E.; Rabinovitch, I. J. (1936). "The insoluble polystyrene". Trans. Faraday Soc. 32: 323–335. doi:10.1039/tf9363200323.

- Meisel, I.; Mülhaupt, R. (2003). "The 60th Anniversary of the First Polymer Journal ("Die Makromolekulare Chemie"): Moving to New Horizons". Macromolecular Chemistry and Physics. 204 (2): 199. doi:10.1002/macp.200290078.

- The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1953 (accessed Mar 2006).

- "Hermann Staudinger and the Foundation of Polymer Science". International Historic Chemical Landmarks. American Chemical Society. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

References

- Helmut Ringsdorf (2004). "Hermann Staudinger and the Future of Polymer Research Jubilees – Beloved Occasions for Cultural Piety". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 43 (9): 1064–1076. doi:10.1002/anie.200330071. PMID 14983439.

- Heinrich Hopff (1969). "Hermann Staudinger 1881–1965". Chemische Berichte. 102 (5): XLI–XLVIII. doi:10.1002/cber.19691020502.

- Ogilvie, Marilyn Bailey; Harvey, Joy Dorothy (2000). The Biographical Dictionary of Women in Science: L-Z. New York, New York: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-92040-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Works by or about Hermann Staudinger at Internet Archive

- Hermann Staudinger on Nobelprize.org

- Staudinger's Nobel Lecture Macromolecular Chemistry