Dehumanization

Dehumanization is the denial of full humanness in others and the cruelty and suffering that accompanies it.[1][2] A practical definition refers to dehumanization as the viewing and treatment of other persons as if they lack the mental capacities that is commonly attributed to human beings.[3] In this definition, every act or thought that treats a person as "less than" human is an act of dehumanization.[4]

Dehumanization is one technique in incitement to genocide.[5]

Conceptualizations

Behaviorally, dehumanization describes a disposition towards others that debases the others' individuality as either an "individual" species or an "individual" object (e.g. someone who acts inhumanely towards humans). As a process, dehumanization may be understood as the opposite of personification, a figure of speech in which inanimate objects or abstractions are endowed with human qualities; dehumanization then is the disendowment of these same qualities or a reduction to abstraction.

In almost all contexts, dehumanization is used pejoratively along with a disruption of social norms, with the former applying to the actor(s) of behavioral dehumanization and the latter applying to the action(s) or processes of dehumanization. For instance, there is the case of dehumanization for those who are perceived as lacking in culture or civility, which are concepts that are believed to distinguish humans from animals.[6] As social norms define what humane behavior is, reflexively these same social norms define what human behavior is not, or what is inhumane. Dehumanization differs from inhumane behaviors or processes in its breadth to include the emergence of new competing social norms. This emergence then is the action of dehumanization until the old norms lose out to the competing new norms, which will then redefine the action of dehumanization. If the new norms lose acceptance then the action remains one of dehumanization and its severity is comparative to past examples throughout history. However, dehumanization's definition remains in a reflexive state of a type-token ambiguity relative to both scales individual and societal.

Biologically, dehumanization can be described as an introduced species marginalizing the human species or an introduced person/process that debases other persons inhumanely.

In political science and jurisprudence, the act of dehumanization is the inferential alienation of human rights or denaturalization of natural rights, a definition contingent upon presiding international law rather than social norms limited by human geography. In this context, specialty within species need not apply to constitute global citizenship or its inalienable rights; these both are inherited by human genome.

It is theorized to take on two forms: animalistic dehumanization, which is employed on a largely intergroup basis, and mechanistic dehumanization, which is employed on a largely interpersonal basis.[7] Dehumanization can occur discursively (e.g., idiomatic language that likens certain human beings to non-human animals, verbal abuse, erasing one's voice from discourse), symbolically (e.g., imagery), or physically (e.g., chattel slavery, physical abuse, refusing eye contact). Dehumanization often ignores the target's individuality (i.e., the creative and interesting aspects of their personality) and can hinder one from feeling empathy or properly understanding a stigmatized group of people.[8]

Dehumanization may be carried out by a social institution (such as a state, school, or family), interpersonally, or even within the self. Dehumanization can be unintentional, especially on the part of individuals, as with some types of de facto racism. State-organized dehumanization has historically been directed against perceived political, racial, ethnic, national, or religious minority groups. Other minoritized and marginalized individuals and groups (based on sexual orientation, gender, disability, class, or some other organizing principle) are also susceptible to various forms of dehumanization. The concept of dehumanization has received empirical attention in the psychological literature.[9][10] It is conceptually related to infrahumanization,[11] delegitimization,[12] moral exclusion,[13] and objectification.[14] Dehumanization occurs across several domains; is facilitated by status, power, and social connection; and results in behaviors like exclusion, violence, and support for violence against others.

“Dehumanisation is viewed as a central component to intergroup violence because it is frequently the most important precursor to moral exclusion, the process by which stigmatized groups are placed outside the boundary in which moral values, rules, and considerations of fairness apply.”[15]

David Livingstone Smith, director and founder of The Human Nature Project at the University of New England, argues that historically, human beings have been dehumanizing one another for thousands of years.[16] In his work “The Paradoxes of Dehumanization,” Smith proposes that dehumanization simultaneously regards people as human and subhuman. This paradox comes to light, as Smith identifies, because the reason people are dehumanized is so their human attributes can be taken advantage of. [17]

Humanness

In Herbert Kelman's work on dehumanization, humanness has two features: "identity" (i.e., a perception of the person "as an individual, independent and distinguishable from others, capable of making choices") and "community" (i.e., a perception of the person as "part of an interconnected network of individuals who care for each other"). When a target's agency and embeddedness in a community are denied, they no longer elicit compassion or other moral responses, and may suffer violence as a result.[18]

Objectification of Women

Fredrickson and Roberts argued that the sexual objectification of women extends beyond pornography (which emphasizes women's bodies over their uniquely human mental and emotional characteristics) to society generally. There is a normative emphasis on female appearance that causes women to take a third-person perspective on their bodies.[19] The psychological distance women may feel from their bodies might cause them to dehumanize themselves. Some research has indicated that women and men exhibit a "sexual body part recognition bias," in which women's sexual body parts are better recognized when presented in isolation than in the context of their entire bodies, whereas men's sexual body parts are better recognized in the context of their entire bodies than in isolation.[20] Men who dehumanize women as either animals or objects are more liable to rape and sexually harass women and display more negative attitudes toward female rape victims.[21]

Martha Nussbaum (1999) identified seven components of objectification: "instrumentality," "denial of autonomy," "inertness," "fungibility," "violability," "ownership," and "denial of subjectivity."[22]

History

Colonialization in the Americas

In Martin Luther King Jr.'s book on civil rights Why We Can't Wait, he explains "Our nation was born in genocide when it embraced the doctrine that the original American, the Indian, was an inferior race."[23]

Mi'kmaq elder and human rights activist Daniel N. Paul has researched written extensively of historic accounts of atrocious acts of violence against First Nations peoples in North America. His work states European colonialism in Canada and America was a subjugation of the indigenous peoples and is an unequivocal violent series of crimes against humanity which has been unparalleled historically. Tens of millions First Nations died at the hands of European invaders in an attempt to appropriate the entirety of the land. Those hundreds of diverse civilizations and communities who thrived across North America thousands of years before the exploits of Christopher Columbus were ultimately destroyed. Dehumanization occurred in the form of barbaric genocidal processes of murder, rape, starvation, enslavement, allocation, and germ warfare. Of the myriad of ways, the colonists performed ethnic cleansing, one of the most frequent was the practice of bounty hunting and scalping—where colonial conquerors would raid communities and remove the scalps of children and adults. This war crime of scalping was most prevalent when maritime colonialists repeatedly attempted to eradicate Daniel N. Paul's ancestors, the Mi'kmaq. Scalping was common practice in many United States areas all the way until the 1860s in an attempt to completely wipe out the remaining First Nations.[24]

Causes and facilitating factors

Several lines of psychological research relate to the concept of dehumanization. Infrahumanization suggests that individuals think of and treat outgroup members as "less human" and more like animals;[11] while Irenaus Eibl-Eibesfeld uses the term pseudo-speciation, a term that he borrowed from the psychoanalyst Erik Erikson, to imply that the dehumanized person or persons are being regarded as not members of the human species.[25] Specifically, individuals associate secondary emotions (which are seen as uniquely human) more with the ingroup than with the outgroup. Primary emotions (those that are experienced by all sentient beings, both humans and other animals) and are found to be more associated with the outgroup.[11] Dehumanization is intrinsically connected with violence. Often, one cannot do serious injury to another without first dehumanizing him or her in one's mind (as a form of rationalization.) Military training is, among other things, a systematic desensitization and dehumanization of the enemy, and servicemen and women may find it psychologically necessary to refer to the enemy as an animal or other non-human beings. Lt. Col. Dave Grossman has shown that without such desensitization it would be difficult, if not impossible for someone to kill another human, even in combat or under threat to their own lives.[26]

Delegitimization is the "categorization of groups into extreme negative social categories which are excluded from human groups that are considered as acting within the limits of acceptable norms and/or values."[12]

Moral exclusion occurs when outgroups are subject to a different set of moral values, rules, and fairness than are used in social relations with ingroup members.[13] When individuals dehumanize others, they no longer experience distress when they treat them poorly. Moral exclusion is used to explain extreme behaviors like genocide, harsh immigration policies, and eugenics, but it can also happen on a more regular, everyday discriminatory level. In laboratory studies, people who are portrayed as lacking human qualities have been found to be treated in a particularly harsh and violent manner.[27][28][29]

Dehumanized perception has been indicated to occur when a subject experiences low frequencies of activation within their social cognition neural network.[30] This includes areas of neural networking such as the superior temporal sulcus and the medial prefrontal cortex.[31] A study by Frith & Frith in 2001 suggests the criticality of social interaction within a neural network has tendencies for subjects to dehumanize those seen as disgust-inducing leading to social disengagement.[32] Tasks involving social cognition typically activate the neural network responsible for subjective projections of disgust-inducing perceptions and patterns of dehumanization. "Besides manipulations of target persons, manipulations of social goals validate this prediction: Inferring preference, a mental-state inference, significantly increases MPFC and STS activity to these otherwise dehumanized targets."[33] A 2007 study by Harris, McClure, van den Bos, Cohen & Fiske suggest a subject's mental reliability towards dehumanizing social cognition due to the decrease of neural activity towards the projected target, replicating across stimuli and contexts.[34]

While social distance from the outgroup target is a necessary condition for dehumanization, some research suggests that it is not sufficient. Psychological research has identified high status, power, and social connection as additional factors that influence whether dehumanization will occur. If being an outgroup member was all that was required to be dehumanized, dehumanization would be far more prevalent. However, only members of high status groups associate humanity more with ingroup than the outgroup. Members of low status groups exhibit no differences in associations with humanity. Having high status makes one more likely to dehumanize others.[35] Low status groups are more associated with human nature traits (warmth, emotionalism) than uniquely human traits, implying that they are closer to animals than humans because these traits are typical of humans but can be seen in other species.[36] In addition, another line of work found that individuals in a position of power were more likely to objectify their subordinates, treating them as a means to one's own end rather than focusing on their essentially human qualities.[37] Finally, social connection, thinking about a close other or being in the actual presence of a close other, enables dehumanization by reducing attribution of human mental states, increasing support for treating targets like animals, and increasing willingness to endorse harsh interrogation tactics.[38] This is surprising because social connection has documented benefits for personal health and well-being but appears to impair intergroup relations.

Neuroimaging studies have discovered that the medial prefrontal cortex—a brain region distinctively involved in attributing mental states to others—shows diminished activation to extremely dehumanized targets (i.e., those rated, according to the stereotype content model, as low-warmth and low-competence, such as drug addicts or homeless people).[39][40]

Race and ethnicity

Dehumanization often occurs as a result of conflict in an intergroup context. Ethnic and racial others are often represented as animals in popular culture and scholarship. There is evidence that this representation persists in the American context with African Americans implicitly associated with apes. To the extent that an individual has this dehumanizing implicit association, they are more likely to support violence against African Americans (e.g., jury decisions to execute defendants).[41] Historically, dehumanization is frequently connected to genocidal conflicts in that ideologies before and during the conflict link victims to rodents/vermin.[7] Immigrants are also dehumanized in this manner.[42] In the 1900s, the Australian Constitution and British Government partook in an Act to federate the Australian states. Section 51 (xxvi) and 127 were two provisions that dehumanised Aboriginals. 51. The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have the power to make laws for the peace, order, and good government of the Commonwealth with respect to: (xxvi) The people of any race, other than the Aboriginal people in any state, for whom it is deemed necessary to make special laws. 127. In reckoning the numbers of the people of the Commonwealth, or of a state or other part of the Commonwealth, Aboriginal natives shall not be counted. In 1902 the Commonwealth Franchise Act was passed, this categorically denied Aboriginals from the right to vote. Indigenous Australians were not allowed social security benefits e.g. Aged pensions and maternity allowances. However, these benefits were provided to other non-Indigenous Australians by the Commonwealth Government. Aboriginals in rural areas were discriminated and controlled as to where and how they could marry, work, live, and their movements were restricted.[43]

Language

Dehumanization and dehumanized perception can occur as a result of the language used to describe groups of people. Words such as migrant, immigrant, and expatriate are assigned to foreigners based on their social status and wealth, rather than ability, achievements, and political alignment. Expatriate has been found to be a word to describe the privileged, often light-skinned people newly residing in an area and has connotations which suggest ability, wealth, and trust. Meanwhile, the word immigrant is used to describe people coming to a new area to reside and infers a much less desirable meaning. Further, "immigrant" is a word that can be paired with "illegal," which harbours a deeply negative connotation to those projecting social cognition towards the other. The misuse and perpetual misuse of these words used to describe the other in the English language can alter the perception of a group in a derogatory way. "Most of the time when we hear [illegal immigrant] used, most of the time the shorter version 'illegals' is being used as a noun, which implies that a human being is perpetually illegal. There is no other classification that I’m aware of where the individual is being rendered as illegal as opposed to the actions of that individuals."[44]

A series of examinations of language sought to find if there was a direct relation between homophobic epithets and social cognitive distancing towards a group of homosexuals, a form of dehumanization. These epithets (e.g., faggot) were thought to function as dehumanizing labels because of their tendency to act as labels of deviance. In both studies, subjects were shown a homophobic epithet, its labelled category, or unspecific insult. Subjects were later prompted to associate words of animal and human connotations to both heterosexuals and homosexuals. The results found that the malignant language, when compared to the unspecific insult and categorized labels, subjects would not connect the human connotative words with homosexuals. Further, the same assessment was done to measure effects the language may have on the physical distancing between the subject and homosexuals.Similarly to the prior associative language study, it was found that subjects became more physically distant to the homosexual, indicating the malignant language could encourage dehumanization, cognitive and physical distancing in ways that other forms of malignant language does not.[45]

Human anatomy

In the United States of America, Americans of African ancestry were dehumanised by being classified as non-human primates. The United States of America Constitution that took place in 1787 stated when collecting census data "all other persons" in reference to enslaved Africans will be counted as three-fifths of a human being. In the 1990s reportedly California State Police classified incidents involving young men of African ancestry as no humans involved. A California police officer who was also involved in the Rodney King beating described a dispute between an American couple with African ancestry as "something right out of gorillas in the mist." Franz Boas and Charles Darwin hypothesized that there may be an evolution process among primates. Monkeys and apes were least evolved, then savage and deformed anthropoids which referred to people of African ancestry, to Caucasians as most evolved.[46]

Government-led dehumanization

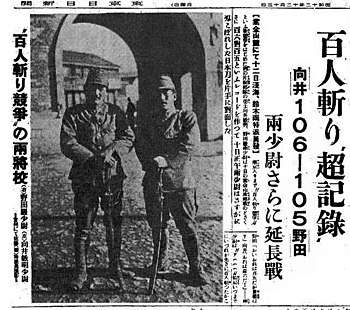

Sociologists and historians often view dehumanization as essential to war. Governments sometimes represent "enemy" civilians or soldiers as less than human so that voters will be more likely to support a war they may otherwise consider mass murder. Dictatorships use the same process to prevent opposition by citizens. Such efforts often depend on preexisting racist, sectarian, or otherwise biased beliefs, which governments play upon through various types of media, presenting "enemies" as barbaric, as undeserving of rights, and as threats to the nation. Alternatively, states sometimes present an enemy government or way of life as barbaric and its citizens as childlike and incapable of managing their own affairs. Such arguments have been used as a pretext for colonialism.

The Holocaust during World War II and the Rwandan genocide have both been cited as atrocities facilitated by a government sanctioned dehumanization of its citizens. In terms of the Holocaust, government proliferated propaganda created a culture of dehumanization of the Jewish population. Crimes like lynching (especially in the United States) are often thought of as the result of popular bigotry and government apathy.

Anthropologists Ashley Montagu and Floyd Matson famously wrote that dehumanization might well be considered "the fifth horseman of the apocalypse" because of the inestimable damage it has dealt to society.[47] When people become things, the logic follows, they become dispensable, and any atrocity can be justified.

Dehumanization can be seen outside of overtly violent conflicts, as in political debates where opponents are presented as collectively stupid or inherently evil. Such "good versus evil" claims help end substantive debate (see also thought-terminating cliché).

Property actions

Several scholars have written on how dehumanization also occurs in the property takings (where the government is involved in taking away individuals' property without just cause and recompense) realm. Dehumanization, as described by Professor Bernadette Atuahene, occurs when the government fails to recognize the humanity of an individual or group.[48][49] Dehumanization through the use of racial slurs, disguised as mascots, coupled with the historical taking of Native American lands, establishes dignity takings in the context of NFL trademarks, such as the Washington Redskins. American University Washington College of Law Professor Victoria Phillips relied on interview data to show that, despite the team's declared intent, most Native Americans find the use of the term "Redskins" disrespectful and dehumanizing.[50] Phillips, a legal scholar, convincingly argues that the continued registration and use of the Redskins trademark is an appropriation of the cultural identity and imagery of Native Americans that rises to the level of a dignity taking.

Regulatory property actions also dehumanize in the context of mobile trailer home parks. People who live in trailer parks are often dehumanized and colloquially referred to as "trailer trash." The cause of this is that mobile park closings are increasingly common, and—even though called "mobile" homes—many of these homes cannot move or the expense of moving them outweighs their value. University of Colorado – Denver Professor Esther Sullivan explores whether mass evictions spurred by park closings, even if legal, constitute a dignity taking.[51]

Legal scholar Lua Kamal Yuille examines whether gang injunctions qualify as dignity takings, when the dehumanization occurs through prohibitions on certain clothing based on little more than suspicion of illegal action or criminal associations.[52] Yuille investigates a gang injunction in Monrovia, California, which prohibits suspected gang members from engaging in a wide range of activities that would otherwise be legal. They cannot, for example, in public wear "gang clothes," or carry "marking substances" like paint cans, pens, and other writing utensils that can be used for graffiti. Yuille argues that, although the state prevents suspected gang members from using certain property in public, this is only one small part of the taking. The more insidious yet invisible harm is the deprivation of identity property, which she defines as property that implicates how people understand themselves. Additionally, Yuille argues that the state treats young gang members like super predators instead of like the children they, in fact, are. Consequently, the City of Monrovia has subjected suspected gang members to a dignity taking because dehumanization occurs alongside property deprivation.[52]

Media-driven dehumanization

The propaganda model of Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky argues that corporate media are able to carry out large-scale, successful dehumanization campaigns when they promote the goals (profit-making) that the corporations are contractually obliged to maximise.[53][54] In both democracies and dictatorships, state media are also capable of carrying out dehumanization campaigns, to the extent with which the population is unable to counteract the dehumanizing memes.[53]

Non-state actors

Non-state actors—terrorists in particular—have also resorted to dehumanization to further their cause and assuage pangs of guilt. The 1960s terrorist group Weather Underground had advocated violence against any authority figure, and used the "police are pigs" idea to convince members that they were not harming human beings, but simply killing wild animals. Likewise, rhetoric statements such as "terrorists are just scum," is an act of dehumanization.[55]

In science, medicine, and technology

Relatively recent history has seen the relationship between dehumanization and science result in unethical scientific research. The Tuskegee syphilis experiment and the Nazi human experimentation on Jewish people are two such examples. In the former, African Americans with syphilis were recruited to participate in a study about the course of the disease. Even when treatment and a cure were eventually developed, they were withheld from the Black participants so that researchers could continue their study. Similarly, Nazi scientists conducted horrific experiments on Jewish people during the Holocaust. This was justified in the name of research and progress which is indicative of the far reaching effects that the culture of dehumanization had upon this society. When this research came to light, efforts were made to protect participants of future research, and currently institutional review boards exist to safeguard individuals from being taken advantage of by scientists.

In a medical context, the passage of time has served to make some dehumanizing practices more acceptable, not less. While dissections of human cadavers were seen as dehumanizing in the Dark Ages (see History of anatomy), the value of dissections as a training aid is such that they are now more widely accepted. Dehumanization has been associated with modern medicine generally, and specifically, has been suggested as a coping mechanism for doctors who work with patients at the end of life.[7][56] Researchers have identified six potential causes of dehumanization in medicine: deindividuating practices, impaired patient agency, dissimilarity (causes which do not facilitate the delivery of medical treatment), mechanization, empathy reduction, and moral disengagement (which could be argued, do facilitate the delivery of medical treatment).[57]

From the patient's point of view, in some states in America, controversial legislation requires that a woman view the ultrasound image of her fetus before being able to have an abortion. Critics of the law argue that simply seeing an image of the fetus humanizes it, and biases women against abortion.[58] Similarly, a recent study showed that subtle humanization of medical patients appears to improve care for these patients. Radiologists evaluating X-rays reported more details to patients and expressed more empathy when a photo of the patient's face accompanied the X-rays.[59] It appears that the inclusion of the photos counteracts the dehumanization of the medical process.

Dehumanization has applications outside traditional social contexts. Anthropomorphism (i.e., perceiving in nonhuman entities mental and physical capacities that reflect humans) is the inverse of dehumanization, which occurs when characteristics that apply to humans are denied to other humans.[60] Waytz, Epley, and Cacioppo suggest that the inverse of the factors that facilitate dehumanization (e.g., high status, power, and social connection) should facilitate anthropomorphism. That is, a low status, socially disconnected person without power should be more likely to attribute human qualities to pets or electronics than a high-status, high-power, socially connected person.

Researchers have found that engaging in violent video game play diminishes perceptions of both one's own humanity and the humanity of the players who are targets of the violence in the games.[61] While the players are dehumanized, the video game characters that play them are likely anthropomorphized.

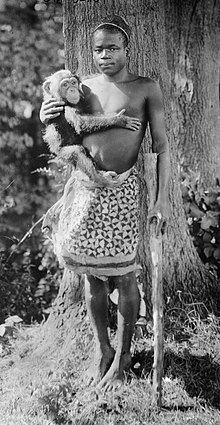

Dehumanization has occurred historically under the pretense of "progress in the name of science." During the St. Louis World's fair in 1904 human zoos exhibited several natives from independent tribes around the globe, most notably a young Congolese man, Ota Benga. Benga's imprisonment was put on display as a public service showcasing “a degraded and degenerate race”. During this period religion was still the driving force behind many political and scientific activities, and because of this, eugenics was widely supported among the most notable US scientific communities, political figures, and industrial elites. After allocating to New York in 1906, public outcry led to the permanent ban and closure of human zoos in the United States.[62]

In art

Francisco Goya, famed Spanish painter and printmaker of the romantic period, often depicted subjectivity involving the atrocities of war and brutal violence conveying the process of dehumanization. In the romantic period of painting martyrdom art was most often a means of deifying the oppressed and tormented, and it was common for Goya to depict evil personalities performing these unjust horrible acts. But it was revolutionary the way the painter broke this convention by dehumanizing these martyr figures. "…one would not know whom the painting depicts, so determinedly has Goya reduced his subjects from martyrs to meat."[63]

See also

References

- Haslam, Nick (2006). "Dehumanization: An Integrative Review". Personality and Social Psychology Review. 10 (3): 252–264. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_4. PMID 16859440 – via Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Spens, Christiana (2014-09-01). "The Theatre of Cruelty: Dehumanization, Objectification & Abu Ghraib". Contemporary Voices: St Andrews Journal of International Relations. 5 (3). doi:10.15664/jtr.946. ISSN 2516-3159.

- Netzer, Giora (2018). Families in the Intensive Care Unit: A Guide to Understanding, Engaging, and Supporting at the Bedside. Cham: Springer. p. 134. ISBN 9783319943367.

- Enge, Erik (2015). Dehumanization as the Central Prerequisite for Slavery. GRIN Verlag. p. 3. ISBN 9783668027107.

- Gordon, Gregory S. (2017). Atrocity Speech Law: Foundation, Fragmentation, Fruition. Oxford University Press. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-19-061270-2.

- Yancey, George (2014). Dehumanizing Christians: Cultural Competition in a Multicultural World. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers. p. 36. ISBN 9781412852678.

- Haslam, Nick (2006). "Dehumanization: An Integrative Review" (PDF). Personality and Social Psychology Review. 10 (3): 252–264. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_4. PMID 16859440. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-06-26.

- Andrighetto, Luca; Baldissarri, Cristina; Lattanzio, Sara; Loughnan, Steve; Volpato, Chiara (2014). "Human-itarian aid? Two forms of dehumanization and willingness to help after natural disasters". British Journal of Social Psychology. 53 (3): 573–584. doi:10.1111/bjso.12066. hdl:10281/53044. ISSN 2044-8309. PMID 24588786.

- Moller, A. C., & Deci, E. L. (2010). "Interpersonal control, dehumanization, and violence: A self-determination theory perspective". Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 13, 41-53. (open access)

- Haslam, Nick; Kashima, Yoshihisa; Loughnan, Stephen; Shi, Junqi; Suitner, Caterina (2008). "Subhuman, Inhuman, and Superhuman: Contrasting Humans with Nonhumans in Three Cultures". Social Cognition. 26 (2): 248–258. doi:10.1521/soco.2008.26.2.248.

- Leyens, Jacques-Philippe; Paladino, Paola M.; Rodriguez-Torres, Ramon; Vaes, Jeroen; Demoulin, Stephanie; Rodriguez-Perez, Armando; Gaunt, Ruth (2000). "The Emotional Side of Prejudice: The Attribution of Secondary Emotions to Ingroups and Outgroups" (PDF). Personality and Social Psychology Review. 4 (2): 186–197. doi:10.1207/S15327957PSPR0402_06. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-06-11.

- Bar-Tal, D. (1989). "Delegitimization: The extreme case of stereotyping and prejudice". In D. Bar-Tal, C. Graumann, A. Kruglanski, & W. Stroebe (Eds.), Stereotyping and prejudice: Changing conceptions. New York, NY: Springer.

- Opotow, Susan (1990). "Moral Exclusion and Injustice: An Introduction". Journal of Social Issues. 46 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1990.tb00268.x.

- Nussbaum, M. C. (1999). Sex and Social Justice. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195112105

- Goof, Phillip; Eberhardt, Jennifer; Williams, Melissa; Jackson, Matthew (2008). "Not yet human: implicit knowledge, historical dehumanization, and contemporary consequences" (PDF). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 94 (2): 292–306. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.94.2.292. PMID 18211178. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- Livingstone Smith, David (2011). Less Than Human: Why We Demean, Enslave, and Exterminate Others. St. Martin’s Press. pp. 336.

- Smith, David Livingstone; Department of Philosophy, Florida State University (2016). "Paradoxes of Dehumanization". Social Theory and Practice. 42 (2): 416–443. doi:10.5840/soctheorpract201642222. ISSN 0037-802X.

- Kelman, H. C. (1976). "Violence without restraint: Reflections on the dehumanization of victims and victimizers". pp. 282-314 in G. M. Kren & L. H. Rappoport (Eds.), Varieties of Psychohistory. New York: Springer. ISBN 0826119409

- Fredrickson, Barbara L.; Roberts, Tomi-Ann (1997). "Objectification Theory: Toward Understanding Women's Lived Experiences and Mental Health Risks". Psychology of Women Quarterly. 21 (2): 173–206. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x.

- Gervais, Sarah J.; Vescio, Theresa K.; Förster, Jens; Maass, Anne; Suitner, Caterina (2012). "Seeing women as objects: The sexual body part recognition bias". European Journal of Social Psychology. 42 (6): 743–753. doi:10.1002/ejsp.1890.

- Rudman, L. A.; Mescher, K. (2012). "Of Animals and Objects: Men's Implicit Dehumanization of Women and Likelihood of Sexual Aggression" (PDF). Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 38 (6): 734–746. doi:10.1177/0146167212436401. PMID 22374225.

- Martha C. Nussbaum (4 February 1999). Sex and Social Justice. Oxford University Press. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-19-535501-7.

- "Reflection today: "Our nation was born in genocide when it embraced the doctrin..." Yale University. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- "AMERICAN INDIANS DEHUMANIZED BY DEMONIZING PROPAGANDA". www.danielnpaul.com. Retrieved 2015-12-08.

- Eibl-Eibisfeldt, Irenäus (1979). The Biology of Peace and War: Men, Animals and Aggression. New York Viking Press.

- Grossman, Dave Lt. Col. (1996). On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society. Back Bay Books. ISBN 978-0-316-33000-8.

- Bandura, Albert (2002). "Selective Moral Disengagement in the Exercise of Moral Agency" (PDF). Journal of Moral Education. 31 (2): 101–119. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.473.2026. doi:10.1080/0305724022014322.

- Bandura, Albert; Barbaranelli, Claudio; Caprara, Gian Vittorio; Pastorelli, Concetta (1996). "Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency" (PDF). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 71 (2): 364–374. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.458.572. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.71.2.364.

- Bandura, Albert; Underwood, Bill; Fromson, Michael E (1975). "Disinhibition of aggression through diffusion of responsibility and dehumanization of victims" (PDF). Journal of Research in Personality. 9 (4): 253–269. doi:10.1016/0092-6566(75)90001-X.

- Amodio, David M.; Frith, Chris D. (2006-04-01). "Meeting of minds: the medial frontal cortex and social cognition". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 7 (4): 268–277. doi:10.1038/nrn1884. ISSN 1471-003X. PMID 16552413.

- Harris, Lasana T.; Fiske, Susan T. (2006-10-01). "Dehumanizing the lowest of the low: neuroimaging responses to extreme out-groups". Psychological Science. 17 (10): 847–853. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01793.x. ISSN 0956-7976. PMID 17100784.

- Frith, Chris D.; Frith, Uta (2007-08-21). "Social cognition in humans". Current Biology. 17 (16): R724–732. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.068. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 17714666.

- Harris, Lasana T.; Fiske, Susan T. (2007-03-01). "Social groups that elicit disgust are differentially processed in mPFC". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2 (1): 45–51. doi:10.1093/scan/nsl037. ISSN 1749-5024. PMC 2555430. PMID 18985118.

- Harris, Lasana T.; McClure, Samuel M.; van den Bos, Wouter; Cohen, Jonathan D.; Fiske, Susan T. (2007-12-01). "Regions of the MPFC differentially tuned to social and nonsocial affective evaluation". Cognitive, Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience. 7 (4): 309–316. doi:10.3758/cabn.7.4.309. ISSN 1530-7026. PMID 18189004.

- Capozza, D.; Andrighetto, L.; Di Bernardo, G. A.; Falvo, R. (2011). "Does status affect intergroup perceptions of humanity?". Group Processes & Intergroup Relations. 15 (3): 363–377. doi:10.1177/1368430211426733.

- Loughnan, S.; Haslam, N.; Kashima, Y. (2009). "Understanding the Relationship between Attribute-Based and Metaphor-Based Dehumanization". Group Processes & Intergroup Relations. 12 (6): 747–762. doi:10.1177/1368430209347726.

- Gruenfeld, Deborah H.; Inesi, M. Ena; Magee, Joe C.; Galinsky, Adam D. (2008). "Power and the objectification of social targets". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 95 (1): 111–127. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.95.1.111. PMID 18605855.

- Waytz, Adam; Epley, Nicholas (2012). "Social connection enables dehumanization". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 48 (1): 70–76. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2011.07.012.

- Harris, L. T.; Fiske, S. T. (2006). "Dehumanizing the Lowest of the Low: Neuroimaging Responses to Extreme Out-Groups" (PDF). Psychological Science. 17 (10): 847–853. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01793.x. PMID 17100784. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-05-13.

- Harris, L. T.; Fiske, S. T. (2007). "Social groups that elicit disgust are differentially processed in mPFC". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2 (1): 45–51. doi:10.1093/scan/nsl037. PMC 2555430. PMID 18985118.

- Goff, Phillip Atiba; Eberhardt, Jennifer L.; Williams, Melissa J.; Jackson, Matthew Christian (2008). "Not yet human: Implicit knowledge, historical dehumanization, and contemporary consequences". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 94 (2): 292–306. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.94.2.292. PMID 18211178.

- O'Brien, Gerald (2003). "Indigestible Food, Conquering Hordes, and Waste Materials: Metaphors of Immigrants and the Early Immigration Restriction Debate in the United States" (PDF). Metaphor and Symbol. 18 (1): 33–47. doi:10.1207/S15327868MS1801_3.

- "About the 1967 Referendum" (PDF). Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 April 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- Koutonin, Mawuna Remarque (2015-03-13). "Why are white people expats when the rest of us are immigrants?". the Guardian. Retrieved 2015-12-08.

- Fasoli, Fabio; Paladino, Maria Paola; Carnaghi, Andrea; Jetten, Jolanda; Bastian, Brock; Bain, Paul G. (2015-01-01). "Not "just words": Exposure to homophobic epithets leads to dehumanizing and physical distancing from gay men" (PDF). European Journal of Social Psychology. 46 (2): 237–248. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2148. hdl:10071/12705. ISSN 1099-0992.

- Goof, Phillip; Eberhardt, Jennifer; Williams, Melissa; Jackson, Matthew (2008). "Not yet human: implicit knowledge, historical dehumanization, and contemporary consequences" (PDF). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 94 (2): 292–306. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.94.2.292. PMID 18211178. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- Montagu, Ashley and Matson, Floyd W. (1983) The dehumanization of man, McGraw-Hill, Preface, p. xi, "For that reason this sickness of the soul might well be called the 'Fifth Horseman of the Apocalypse.' Its more conventional name, of course, is dehumanization."

- Atuahene, Bernadette (2016). "Dignity Takings and Dignity Restoration: Creating a New Theoretical Framework for Understanding Involuntary Property Loss and the Remedies Required". Law & Social Inquiry. 41 (4): 796–823. doi:10.1111/lsi.12249. ISSN 0897-6546.

- Atuahene, Bernadette, Sifuna Okwethu : we want what's ours, OCLC 841493699

- Phillips, Victoria (2017). "Beyond Trademark: The Washington Redskins Case and the Search for Dignity". Chicago Kent Law Review. 92: 1061–1086.

- Sullivan, Esther (2018-03-06). "Dignity Takings and "Trailer Trash": The Case Of Mobile Home Park Mass Evictions". Chicago-Kent Law Review. 92 (3): 937. ISSN 0009-3599.

- Yuille, Lua (2018-03-06). "Dignity Takings in Gangland's Suburban Frontier". Chicago-Kent Law Review. 92 (3): 793. ISSN 0009-3599.

- Herman, Edward S. and Noam Chomsky. (1988). Manufacturing Consent: the Political Economy of the Mass Media. New York: Pantheon. Page xli

- Thomas Ferguson. (1987). Golden Rule: The Investment Theory of Party Competition and the Logic of Money-Driven Politics

- Graham, Stephen (2006). "Cities and the 'War on Terror'". International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 30 (2): 255–276. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2006.00665.x.

- Schulman-Green, Dena (2003). "Coping mechanisms of physicians who routinely work with dying patients". OMEGA: Journal of Death and Dying. 47 (3): 253–264. doi:10.2190/950H-U076-T5JB-X6HN.

- Haque, O. S.; Waytz, A. (2012). "Dehumanization in Medicine: Causes, Solutions, and Functions". Perspectives on Psychological Science. 7 (2): 176–186. doi:10.1177/1745691611429706. PMID 26168442. S2CID 1670448.

- Sanger, C (2008). "Seeing and believing: Mandatory ultrasound and the path to a protected choice". UCLA Law Review. 56: 351–408.

- Turner, Y., & Hadas-Halpern, I. (2008, December 3). "The effects of including a patient's photograph to the radiographic examination". Paper presented at Radiological Society of North America, Chicago, IL.

- Waytz, A.; Epley, N.; Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). "Social Cognition Unbound: Insights Into Anthropomorphism and Dehumanization" (PDF). Current Directions in Psychological Science. 19 (1): 58–62. doi:10.1177/0963721409359302. PMC 4020342. PMID 24839358.

- Bastian, Brock; Jetten, Jolanda; Radke, Helena R.M. (2012). "Cyber-dehumanization: Violent video game play diminishes our humanity". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 48 (2): 486–491. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2011.10.009.

- Newkirk, Pamela (2015-06-03). "The man who was caged in a zoo | Pamela Newkirk". the Guardian. Retrieved 2015-12-08.

- Anderson, Emma (2013). The Death and Afterlife of the North American Martyrs. United States: Harvard University Press. p. 91. ISBN 9780674726161.