Gossip

Gossip is a mass medium or rumor, especially about the personal or private affairs of others; the act is also known as dishing or tattling.[1]

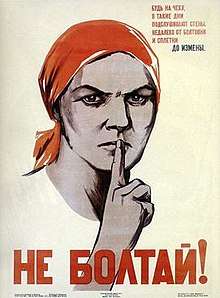

_-_WGA03627.jpg)

Gossip has been researched in terms of its origins in evolutionary psychology,[2] which has found gossip to be an important means for people to monitor cooperative reputations and so maintain widespread indirect reciprocity.[3] Indirect reciprocity is a social interaction in which one actor helps another and is then benefited by a third party. Gossip has also been identified by Robin Dunbar, an evolutionary biologist, as aiding social bonding in large groups.[4]

Etymology

| Look up gossip in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

The word is from Old English godsibb, from god and sibb, the term for the godparents of one's child or the parents of one's godchild, generally very close friends. In the 16th century, the word assumed the meaning of a person, mostly a woman, one who delights in idle talk, a newsmonger, a tattler.[5] In the early 19th century, the term was extended from the talker to the conversation of such persons. The verb to gossip, meaning "to be a gossip", first appears in Shakespeare.

The term originates from the bedroom at the time of childbirth. Giving birth used to be a social event exclusively attended by women. The pregnant woman's female relatives and neighbours would congregate and idly converse. Over time, gossip came to mean talk of others.[6]

Others say that gossip comes from the same root as "gospel" — it is a contraction of "good spiel", meaning a good story.

Functions

Gossip can:[2]

- reinforce – or punish the lack of – morality and accountability

- reveal passive aggression, isolating and harming others

- serve as a process of social grooming

- build and maintain a sense of community with shared interests, information, and values[7]

- begin a courtship that helps one find their desired mate, by counseling others

- provide a peer-to-peer mechanism for disseminating information

Workplace gossip

Mary Gormandy White, a human resource expert, gives the following "signs" for identifying workplace gossip:

- Animated people become silent ("Conversations stop when you enter the room")

- People begin staring at someone

- Workers indulge in inappropriate topics of conversation.[8]

White suggests "five tips ... [to] handle the situation with aplomb:

- Rise above the gossip

- Understand what causes or fuels the gossip

- Do not participate in workplace gossip.

- Allow for the gossip to go away on its own

- If it persists, "gather facts and seek help."[8]

Peter Vajda identifies gossip as a form of workplace violence, noting that it is "essentially a form of attack." Gossip is thought by many to "empower one person while disempowering another" (Hafen). Accordingly, many companies have formal policies in their employee handbooks against gossip.[9] Sometimes there is room for disagreement on exactly what constitutes unacceptable gossip, since workplace gossip may take the form of offhand remarks about someone's tendencies such as "He always takes a long lunch," or "Don’t worry, that’s just how she is."[10]

TLK Healthcare cites as examples of gossip, "tattletailing to the boss without intention of furthering a solution or speaking to co-workers about something someone else has done to upset us." Corporate email can be a particularly dangerous method of gossip delivery, as the medium is semi-permanent and messages are easily forwarded to unintended recipients; accordingly, a Mass High Tech article advised employers to instruct employees against using company email networks for gossip.[11] Low self-esteem and a desire to "fit in" are frequently cited as motivations for workplace gossip. There are five essential functions that gossip has in the workplace (according to DiFonzo & Bordia):

- Helps individuals learn social information about other individuals in the organization (often without even having to meet the other individual)

- Builds social networks of individuals by bonding co-workers together and affiliating people with each other.

- Breaks existing bonds by ostracizing individuals within an organization.

- Enhances one's social status/power/prestige within the organization.

- Inform individuals as to what is considered socially acceptable behavior within the organization.

According to Kurkland and Pelled, workplace gossip can be very serious depending upon the amount of power that the gossiper has over the recipient, which will in turn affect how the gossip is interpreted. There are four types of power that are influenced by gossip:

- Coercive: when a gossiper tells negative information about a person, their recipient might believe that the gossiper will also spread negative information about them. This causes the gossiper's coercive power to increase.

- Reward: when a gossiper tells positive information about a person, their recipient might believe that the gossiper will also spread positive information about them. This causes the gossiper's reward power to increase.

- Expert: when a gossiper seems to have very detailed knowledge of either the organization's values or about others in the work environment, their expert power becomes enhanced.

- Referent: this power can either be reduced OR enhanced to a point. When people view gossiping as a petty activity done to waste time, a gossiper's referent power can decrease along with their reputation. When a recipient is thought of as being invited into a social circle by being a recipient, the gossiper's referent power can increase, but only to a high point where then the recipient begins to resent the gossiper (Kurland & Pelled).

Some negative consequences of workplace gossip may include:[12]

- Lost productivity and wasted time,

- Erosion of trust and morale,

- Increased anxiety among employees as rumors circulate without any clear information as to what is fact and what isn’t,

- Growing divisiveness among employees as people “take sides,"

- Hurt feelings and reputations,

- Jeopardized chances for the gossipers' advancement as they are perceived as unprofessional, and

- Attrition as good employees leave the company due to the unhealthy work atmosphere.

Turner and Weed theorize that among the three main types of responders to workplace conflict are attackers who cannot keep their feelings to themselves and express their feelings by attacking whatever they can. Attackers are further divided into up-front attackers and behind-the-back attackers. Turner and Weed note that the latter "are difficult to handle because the target person is not sure of the source of any criticism, nor even always sure that there is criticism."[13]

It is possible however, that there may be illegal, unethical, or disobedient behavior happening at the workplace and this may be a case where reporting the behavior may be viewed as gossip. It is then left up to the authority in charge to fully investigate the matter and not simply look past the report and assume it to be workplace gossip.

Informal networks through which communication occurs in an organization are sometimes called the grapevine. In a study done by Harcourt, Richerson, and Wattier, it was found that middle managers in several different organizations believed that gathering information from the grapevine was a much better way of learning information than through formal communication with their subordinates (Harcourt, Richerson & Wattier).

Various views

Some see gossip as trivial, hurtful and socially and/or intellectually unproductive. Some people view gossip as a lighthearted way of spreading information. A feminist definition of gossip presents it as "a way of talking between women, intimate in style, personal and domestic in scope and setting, a female cultural event which springs from and perpetuates the restrictions of the female role, but also gives the comfort of validation." (Jones, 1990:243)

In early modern England

In Early Modern England the word "gossip" referred to companions in childbirth, not limited to the midwife. It also became a term for women-friends generally, with no necessary derogatory connotations. (OED n. definition 2. a. "A familiar acquaintance, friend, chum", supported by references from 1361 to 1873). It commonly referred to an informal local sorority or social group, who could enforce socially acceptable behaviour through private censure or through public rituals, such as "rough music", the cucking stool and the skimmington ride.

In Thomas Harman’s Caveat for Common Cursitors 1566 a ‘walking mort’ relates how she was forced to agree to meet a man in his barn, but informed his wife. The wife arrived with her “five furious, sturdy, muffled gossips” who catch the errant husband with “his hosen about his legs” and give him a sound beating. The story clearly functions as a morality tale in which the gossips uphold the social order.[14]

In Sir Herbert Maxwell Bart's The Chevalier of the Splendid Crest [1900] at the end of chapter three the king is noted as referring to his loyal knight "Sir Thomas de Roos" in kindly terms as "my old gossip". Whilst a historical novel of that time the reference implies a continued use of the term "Gossip" as childhood friend as late as 1900.

In Judaism

Judaism considers gossip spoken without a constructive purpose (known in Hebrew as an evil tongue, lashon hara) as a sin. Speaking negatively about people, even if retelling true facts, counts as sinful, as it demeans the dignity of man — both the speaker and the subject of the gossip. According to Proverbs 18:8: "The words of a gossip are like choice morsels: they go down to a man's innermost parts."

In Christianity

The Christian perspective on gossip is typically based on modern cultural assumptions of the phenomenon, especially the assumption that generally speaking, gossip is negative speech.[15][16][17] However, due to the complexity of the phenomenon, biblical scholars have more precisely identified the form and function of gossip, even identifying a socially positive role for the social process as it is described in the New Testament.[18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25] Of course, this does not mean that there are not numerous texts in the New Testament that see gossip as dangerous negative speech.

Thus, for example, the Epistle to the Romans associates gossips ("backbiters") with a list of sins including sexual immorality and with murder:

- 28: And even as they did not like to retain God in their knowledge, God gave them over to a reprobate mind, to do those things which are not convenient;

- 29: Being filled with all unrighteousness, fornication, wickedness, covetousness, maliciousness; full of envy, murder, debate, deceit, malignity; whisperers,

- 30: Backbiters, haters of God, despiteful, proud, boasters, inventors of evil things, disobedient to parents,

- 31: Without understanding, covenantbreakers, without natural affection, implacable, unmerciful:

- 32: Who knowing the judgment of God, that they which commit such things are worthy of death, not only do the same, but have pleasure in them that do them. (Romans 1:28-32)

According to Matthew 18, Jesus also taught that conflict resolution among church members ought to begin with the aggrieved party attempting to resolve their dispute with the offending party alone. Only if this did not work would the process escalate to the next step, in which another church member would become involved. After that if the person at fault still would not "hear", the matter was to be fully investigated by the church elders, and if not resolved to be then exposed publicly.

Based on texts like these portraying gossip negatively, many Christian authors generalize on the phenomenon. So, in order to gossip, writes Phil Fox Rose, we "must harden our heart towards the 'out' person. We draw a line between ourselves and them; define them as being outside the rules of Christian charity... We create a gap between ourselves and God's Love." As we harden our heart towards more people and groups, he continues, "this negativity and feeling of separateness will grow and permeate our world, and we'll find it more difficult to access God’s love in any aspect of our lives."[26]

The New Testament is also in favor of group accountability (Ephesians 5:11; 1st Tim 5:20; James 5:16; Gal 6:1-2; 1 Cor 12:26), which may be associated with gossip.

In Islam

Islam considers backbiting the equivalent of eating the flesh of one's dead brother. According to Muslims, backbiting harms its victims without offering them any chance of defense, just as dead people cannot defend against their flesh being eaten. Muslims are expected to treat others like brothers (regardless of their beliefs, skin color, gender, or ethnic origin), deriving from Islam's concept of brotherhood amongst its believers.

In Bahai Faith

Bahais consider backbiting to be the "worst human quality and the most great sin..."[27] Therefore, even murder would be considered less reprobate than backbiting. Baha'u'llah stated, "Backbiting quencheth the light of the heart, and extinguisheth the life of the soul." When someone kills another, it only affects their physical condition. However, when someone gossips, it affects one in a different manner.

In psychology

Evolutionary view

From Robin Dunbar's evolutionary theories, gossip originated to help bond the groups that were constantly growing in size. To survive, individuals need alliances; but as these alliances grew larger, it was difficult if not impossible to physically connect with everyone. Conversation and language were able to bridge this gap. Gossip became a social interaction that helped the group gain information about other individuals without personally speaking to them.

It enabled people to keep up with what was going on in their social network. It also creates a bond between the teller and the hearer, as they share information of mutual interest and spend time together. It also helps the hearer learn about another individual’s behavior and helps them have a more effective approach to their relationship. Dunbar (2004) found that 65% of conversations consist of social topics.[28]

Dunbar (1994) argues that gossip is the equivalent of social grooming often observed in other primate species.[29] Anthropological investigations indicate that gossip is a cross-cultural phenomenon, providing evidence for evolutionary accounts of gossip.[30][31][32]

There is very little evidence to suggest meaningful sex differences in the proportion of conversational time spent gossiping, and when there is a difference, women are only very slightly more likely to gossip compared with men.[29][32][33] Further support for the evolutionary significance of gossip comes from a recent study published in the peer-reviewed journal, Science Anderson and colleagues (2011) found that faces paired with negative social information dominate visual consciousness to a greater extent than positive and neutral social information during a binocular rivalry task.

Binocular rivalry occurs when two different stimuli are presented to each eye simultaneously and the two percepts compete for dominance in visual consciousness. While this occurs, an individual will consciously perceive one of the percepts while the other is suppressed. After a time, the other percept will become dominant and an individual will become aware of the second percept. Finally, the two percepts will alternate back and forth in terms of visual awareness.

The study by Anderson and colleagues (2011) indicates that higher order cognitive processes, like evaluative information processing, can influence early visual processing. That only negative social information differentially affected the dominance of the faces during the task alludes to the unique importance of knowing information about an individual that should be avoided. Since the positive social information did not produce greater perceptual dominance of the matched face indicates that negative information about an individual may be more salient to our behavior than positive.[34]

Gossip also gives information about social norms and guidelines for behavior. Gossip usually comments on how appropriate a behavior was, and the mere act of repeating it signifies its importance. In this sense, gossip is effective regardless of whether it is positive or negative[35] Some theorists have proposed that gossip is actually a pro-social behavior intended to allow an individual to correct their socially prohibitive behavior without direct confrontation of the individual. By gossiping about an individual’s acts, other individuals can subtly indicate that said acts are inappropriate and allow the individual to correct their behavior (Schoeman 1994).

Perception of those who gossip

Individuals who are perceived to engage in gossiping regularly are seen as having less social power and being less liked. The type of gossip being exchanged also affects likeability, whereby those who engage in negative gossip are less liked than those who engage in positive gossip.[36] In a study done by Turner and colleagues (2003), having a prior relationship with a gossiper was not found to protect the gossiper from less favorable personality-ratings after gossip was exchanged. In the study, pairs of individuals were brought into a research lab to participate. Either the two individuals were friends prior to the study or they were strangers scheduled to participate at the same time. One of the individuals was a confederate of the study, and they engaged in gossiping about the research assistant after she left the room. The gossip exchanged was either positive or negative. Regardless of gossip type (positive versus negative) or relationship type (friend versus stranger) the gossipers were rated as less trustworthy after sharing the gossip.[37]

Walter Block has suggested that while gossip and blackmail both involve the disclosure of unflattering information, the blackmailer is arguably ethically superior to the gossip.[38] Block writes: "In a sense, the gossip is much worse than the blackmailer, for the blackmailer has given the blackmailed a chance to silence him. The gossip exposes the secret without warning." The victim of a blackmailer is thus offered choices denied to the subject of gossip, such as deciding if the exposure of his or her secret is worth the cost the blackmailer demands. Moreover, in refusing a blackmailer's offer one is in no worse a position than with the gossip. Adds Block, "It is indeed difficult, then, to account for the vilification suffered by the blackmailer, at least compared to the gossip, who is usually dismissed with slight contempt and smugness."

Contemporary critiques of gossip may concentrate on or become subsumed in the discussion of social media such as Facebook.[39]

See also

- Altruism

- Bullying

- Blind Item

- Circle of Friends

- Communication in small groups

- Curiosity

- False dilemma

- Gossip magazines

- Impression management

- Interpersonal relationship

- Libel

- Misinformation

- Personal network

- Popularity

- Respectability

- Rumor

- Scandal

- Sexual selection in human evolution

- Social perception

- Social status

- Word of mouth

- Yenta

- Backbiting

References

- "Gossip - Define Gossip at Dictionary.com". Dictionary.com.

- McAndrew, Frank T. (October 2008). "The Science of Gossip: Why we can't stop ourselves". Scientific American.

- Sommerfeld, RD; Krambeck, HJ; Semmann, D; Milinski, M (2007). "Gossip as an alternative for direct observation in games of indirect reciprocity". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 104 (44): 17435–40. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10417435S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0704598104. PMC 2077274. PMID 17947384.

- Dunbar, RI (2004). "Gossip in evolutionary perspective". Review of General Psychology. 8 (2): 100–110. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.530.9865. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.8.2.100.

- OED

- "If Walls Could Talk: The History of the Home (Bedroom), Lucy Worsley, BBC"

-

Abercrombie, Nicholas (2004). Sociology: A Short Introduction. Short Introductions. Cambridge: Polity Press. pp. 122–152. ISBN 978-0745625416.

[...] I described a study of the role of gossip in controlling the lives of young people in a London Punjabi community. Gossip is effectively a device for the assertion and maintenance of the background assumptions about the way that a community lives its life.

- Jeanne Grunert, "When Gossip Strikes," OfficePro, January/February 2010, pp. 16-18, at 17, found at IAAP website. Accessed March 9, 2010.

- New Jersey Hearsay Evidence, Human Resource Blog.

- The Culture Shock Archived 2007-11-27 at the Wayback Machine, Tami Kyle, TLK Connections, Summer 2005.

- Companies must spell out employee e-mail policies, Warren E. Agin, Swiggart & Agin, LLC, Mass High Tech, November 18, 1996.

- Workplace Gossip Archived 2007-11-27 at the Wayback Machine, Kit Hennessy, LPC, CEAP.

- Conflict in organizations: Practical solutions any manager can use; Turner, Stephen P. (University of South Florida); Weed, Frank; 1983.

- Bernard Capp, When Gossips Meet: Women, Family and Neighbourhood in Early Modern England, Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-19-925598-9

- Meng, Margaret (2008). "Gossip: Killing Us Softly". Homiletic and Pastoral Review. 109: 26–31.

- Sedler, M.D. (2001). Stop the Runaway Conversation: Take Control Over Gossip and Criticism. Grand Rapids: Chosen.

- Mitchell, Mathew C. (2013). Resisting Gossip: Winning the War of the Wagging Tongue. Fort Washington: CLC Publications.

- Daniels, John W. (2013). Gossiping Jesus: The Oral Processing of Jesus in John's Gospel. Eugene: Pickwick Publications.

- Daniels, John W. (2012). "Gossip in the New Testament." Biblical Theology Bulletin 42/4. pp. 204-213.

- Botha, Pieter J. J. (1998). "Paul and Gossip: A Social Mechanism in Early Christian Communities". Neotestamentica. 32: 267–288.

- Botha, Pieter J. J. (1993). "The Social Dynamics of the Early Transmission of the Jesus Tradition". Neotestamentica. 27: 205–231.

- Kartzow, Marianne B (2005). "Female Gossipers and their Reputation in the Pastoral Epistles". Neotestamentica. 39: 255–271.

- Kartzow, Marianne B. (2009). Gossip and Gender: Othering of Speech in the Pastoral Epistles. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Kartzow, Marianne B. (2010) "Resurrection as Gossip: Representations of Women in Resurrection Stories of the Gospels." Lectio Difficilior 1.

- Rohrbaugh, Richard L. (2007). "Gossip in the New Testament." The New Testament in Cross-Cultural Perspective. Eugene: Cascade Books.

- Phil Fox Rose, "Gossip hardens our hearts", Patheos. Accessed February 23, 2013.

- "Backbiting". Bahai Quotes.com. Archived from the original on 24 September 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- Dunbar, R (2004). "Gossip in evolutionary perspective". Review of General Psychology. 8 (2): 100–110. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.8.2.100.

- Dunbar, R.I.M. (1994). Grooming, gossip, and the evolution of language. London: Faver & Faber.

- Besnier, N (1989). "Information withholding as a manipulative and collusive strategy in Nukulaelae gossip". Language in Society. 18 (3): 315–341. doi:10.1017/s0047404500013634.

- Gluckman, M (1963). "Gossip and scandal". Current Anthropology. 4: 307–316. doi:10.1086/200378.

- Haviland, J.B. (1977). "Gossip as competition in Zinacantan". Journal of Communication. 27: 186–191. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1977.tb01816.x.

- Foster, E.K. (2004). "Research on gossip: Taxonomy, methods, and future directions". Review of General Psychology. 8 (2): 78–99. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.8.2.78.

- Anderson, E.; Siegel, E.H.; Bliss-Moreau, E.; Barrett, L.F. (2011). "The visual impact of gossip". Science Magazine. 332 (6036): 1446–1448. Bibcode:2011Sci...332.1446A. doi:10.1126/science.1201574. PMC 3141574. PMID 21596956.

- Baumeister, R. F.; Zhang, L.; Vohs, K. D. (2004). "Gossip as cultural learning". Review of General Psychology. 8 (2): 111–121. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.8.2.111.

- Farley, S (2011). "Is gossip power? The inverse relationship between gossip, power, and likability". European Journal of Social Psychology. 41 (5): 574–579. doi:10.1002/ejsp.821. hdl:11603/4030.

- Turner, M. M.; Mazur, M.A.; Wendel, N.; Winslow, R. (2003). "Relationship ruin or social glue? The joint effect of relationship type and gossip valence on liking, trust, and expertise". Communication Monographs. 70: 129–141. doi:10.1080/0363775032000133782.

- Block, Walter ([1976], 1991, 2008). Defending the Undefendable: The Pimp, Prostitute, Scab, Slumlord, Libeler, Moneylender, and Other Scapegoats in the Rogue's Gallery of American Society Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute, ISBN 978-1-933550-17-6, pp. 42-43, full text online

- Cuonzo, Margaret A. (2010). "15: Gossip and the evolution of facebook". In Wittkower, D. E. (ed.). Facebook and Philosophy: What's on Your Mind?. Popular culture and philosophy series, edited by George A. Reisch. 50. Chicago: Open Court Publishing. p. 173ff. ISBN 9780812696752. Retrieved 23 Apr 2019.

Further reading

- Niko Besnier, 2009: Gossip and the Everyday Production of Politics. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3338-1

- Niko Besnier, 1996: Gossip. In Encyclopedia of Cultural Anthropology. David Levinson and Melvin Ember, eds. Vol. 2, pp. 544–547. New York: Henry Holt.

- Besnier, Niko (1994). "The Truth and Other Irrelevant Aspects of Nukulaelae Gossip". Pacific Studies. 17 (3): 1–39.

- Besnier, Niko (1989). "Information Withholding as a Manipulative and Collusive Strategy in Nukulaelae Gossip". Language in Society. 18 (3): 315–341. doi:10.1017/s0047404500013634.

- Birchall, Clare (2006). Knowledge goes pop from conspiracy theory to gossip. Oxford New York: Berg. ISBN 9781845201432. Preview.

- DiFonzo, Nicholas & Prashant Bordia. "Rumor, Gossip, & Urban Legend." Diogenes Vol. 54 (Feb 2007) pg 19-35.

- Ellickson, Robert C. (1991). Order without law: how neighbors settle disputes. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-64168-6.

- Feeley, Kathleen A. and Frost, Jennifer (eds.) When Private Talk Goes Public: Gossip in American History. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

- Robert F. Goodman and Aaron Ben-Zeev, editors: Good Gossip. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 1993. ISBN 0-7006-0669-6

- Hafen, Susan. "Organizational Gossip: A Revolving Door of Regulation & Resistance." The Southern Communication Journal Vol. 69, No. 3 (Spring 2004) pg 223

- Harcourt, Jules, Virginia Richerson, and Mark J Wattier. "A National Study of Middle Managers' Assessment of Organizational Communication Quality." Journal of Business Communication Vol. 28, No. 4 (Fall 1991) pg 348-365

- Jones, Deborah, 1990: 'Gossip: notes on women's oral culture'. In: Cameron, Deborah. (editor) The Feminist Critique of Language: A Reader. London/New York: Routledge, 1990, pp. 242–250. ISBN 0-415-04259-3. Cited online in Rash, 1996.

- Kenny, Robert Wade, 2014: Gossip. In Encyclopedia of Lying and Deception. Timothy R. Levine, ed. Vol. 1, pp. 410–414. Los Angeles: Sage Press.

- Kurland, Nancy B. & Lisa Hope Pelled. "Passing the Word: Toward a Model of Gossip & Power in the Workplace." The Academy of Management Review Vol. 25, No. 2 (April 2000) pg 428-438

- Phillips, Susan (2010), Transforming Talk: The Problem with Gossip in Late Medieval England, Penn State Press, ISBN 9780271047393

- Rash, Felicity (1996). "Rauhe Männer - Zarte Frauen: Linguistic and Stylistic Aspects of Gender Stereotyping in German Advertising Texts 1949-1959" (1). Web Journal of Modern Language Linguistics. Retrieved August 8, 2006. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Spacks, Patricia Ann Meyer (1985), Gossip, New York: =Knopf, ISBN 978-0-394-54024-5

External links

| Look up gossip in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gossip. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Gossip |

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 12 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Ronald de Sousa (U Toronto) on Gossip

- "Go Ahead. Gossip May Be Virtuous" New York Times article by Patricia Cohen 2002-08-10 (requires registration)

- Emrys Westacott (Alfred U) The Ethics of Gossiping

- Robin Dunbar, Coevolution of neocortical size, group size and language in humans (pre-publication version) "Analysis of a sample of human conversations shows that about 60% of time is spent gossiping about relationships and personal experiences."

- Benjamin Brown, From Principles to Rules and from Musar to Halakhah - The Hafetz Hayim's Rulings on Libel and Gossip.

- Gossip and gender differences: a content analys Gossip and gender differences: a content analysis approach is approach