Sectarianism

Sectarianism is a form of prejudice, discrimination, or hatred arising from attaching relations of inferiority and superiority to differences between subdivisions within a group. Common examples are denominations of a religion, ethnic identity, class, or region for citizens of a state and factions of a political movement.

The ideological underpinnings of attitudes and behaviours labelled as sectarian are extraordinarily varied. Members of a religious, national or political group may believe that their own salvation, or the success of their particular objectives, requires aggressively seeking converts from other groups; likewise, adherents of a given faction may believe that the achievement of their own political or religious goals requires the conversion or purging of dissidents within their own sect.

Sometimes a group that is under economic or political pressure will kill or attack members of another group which it regards as responsible for its own decline. It may also more rigidly define the definition of orthodox belief within its particular group or organization, and expel or excommunicate those who do not support this newfound clarified definition of political or religious orthodoxy. In other cases, dissenters from this orthodoxy will secede from the orthodox organisation and proclaim themselves as practitioners of a reformed belief system, or holders of a perceived former orthodoxy. At other times, sectarianism may be the expression of a group's nationalistic or cultural ambitions, or exploited by demagogues.

The phrase "sectarian conflict" usually refers to violent conflict along religious or political lines such as the conflicts between Nationalists and Unionists in Northern Ireland (religious and class-divisions may play major roles as well). It may also refer to general philosophical, political disparity between different schools of thought such as that between Shia and Sunni Muslims. Non-sectarians espouse that free association and tolerance of different beliefs are the cornerstone to successful peaceful human interaction. They espouse political and religious pluralism.

While sectarianism is often labelled as 'religious' and/ or 'political', the reality of a sectarian situation is usually much more complex. In its most basic form sectarianism has been defined as, 'the existence, within a locality, of two or more divided and actively competing communal identities, resulting in a strong sense of dualism which unremittingly transcends commonality, and is both culturally and physically manifest.'[1]

Sectarianization

Various scholars have made a differentiation between "sectarianism" and "sectarianization". While the first describes prejudice, discrimination, and hatred between subdivisions within a group based on their i.e. religious or ethnic identity, the latter describes how sectarianism is mobilized by political actors due to ulterior political motives.[2][3] The use of the word "sectarianism" to explain sectarian violence and its upsurge in i.e. the Middle East is insufficient, as it does not take into account complex political realities.[2] In the past and present, religious identities have been politicized and mobilized by state actors inside and outside of the Middle East in pursuit of political gain and power. The term "sectarianization" conceptualizes this notion.[2] Sectarianization is an active, multi-layered process and a set of practices, not a static condition, that is set in motion and shaped by political actors pursuing political goals.[2][3][4] While religious identity is salient in the Middle East and has contributed to and intensified conflicts across the region, it is the politicization and mobilization of popular sentiments around certain identity markers ("sectarianization") that explains the extent and upsurge of sectarian violence in the Middle East.[2] The Ottoman Tanzimat, European colonialism and authoritarianism are key in the process of sectarianization in the Middle East.[2][3][5][6]

The Ottoman Tanzimat and European colonialism

The Ottoman Tanzimat, a period of Ottoman reform (1839–1876), emerged out of an effort to resist European intervention by emancipating the non-Muslim subjects of the empire, as European powers had started intervening in the region "on a explicitly sectarian basis".[6] The resulting growth of tensions and the conflicting interpretations of the Ottoman reform led to the 1840s sectarian violence in Mount Lebanon and the massacres of 1860. This resulted in "a system of local administration and politics explicitly defined on a narrow communal basis".[6] Sectarianism arose from the confrontation between European colonialism and the Ottoman Empire and was used to mobilize religious identities for political and social purposes.[5]

In the decades that followed, a colonial strategy and technique to assert control and perpetuate power used by the French during their mandate rule of Lebanon was divide and rule.[3] The establishment of the Ja'fari court in 1926, facilitated by the French as a "quasi-colonial institution"[3], provided Shi'a Muslims with sectarian rights through the institutionalization of Shia Islam, and hence gave rise to political Shi’ism. The "variation in the institutionalization of social welfare across different sectarian communities forged and exacerbated social disparities".[7] Additionally, with the standardization, codification and bureaucratization of Shia Islam, a Shi’i collective identity began to form and the Shi’i community started to "practice" sectarianism.[3] "The French colonial state contributed to rendering the Shi‘i community in Jabal ‘Amil and Beirut more visible, more empowered, but also more sectarian, in ways that it had never quite been before."[3] This fundamental transformation, or process of sectarianization, led by the French created a new political reality that paved the way for the "mobilization" and "radicalization" of the Shi’a community during the Lebanese civil war.[3][8]

Authoritarian regimes

In recent years, authoritarian regimes have been particularly prone to sectarianization. This is because their key strategy of survival lies in manipulating sectarian identities to deflect demands for change and justice and preserve and perpetuate their power.[2] Christian communities, and other religious and ethnic minorities in the Middle East, have been socially, economically and politically excluded and harmed primarily by regimes that focus on "securing power and manipulating their base by appeals to Arab nationalism and/or to Islam".[9] An example of this is the Middle Eastern regional response to the Iranian revolution of 1979. Middle Eastern dictatorships backed by the United States, especially Saudi Arabia, feared that the spread of the revolutionary spirit and ideology would affect their power and dominance in the region. Therefore, efforts were made to undermine the Iranian revolution by labeling it as a Shi’a conspiracy to corrupt the Sunni Islamic tradition. This was followed by a rise of anti-Shi’a sentiments across the region and a deterioration of Shi'a-Sunni relations, impelled by funds from the Gulf states.[2] Therefore, the process of sectarianization, the mobilization and politicization of sectarian identities, is a political tool for authoritarian regimes to perpetuate their power and justify violence.[2] Western powers indirectly take part in the process of sectarianization by supporting undemocratic regimes in the Middle East.[4] As Nader Hashemi asserts:

The U.S. invasion of Iraq; the support of various Western governments for the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, which commits war crime upon war crime in Yemen and disseminates poisonous sectarian propaganda throughout the Sunni world; not to mention longstanding Western support for highly repressive dictators who manipulate sectarian fears and anxieties as a strategy of control and regime survival – the "ancient hatreds" narrative [between Sunnis and Shi’as] washes this all away and lays the blame for the regionʹs problems on supposedly trans-historical religious passions. Itʹs absurd in the extreme and an exercise in bad faith.[4]

Religious sectarianism

Wherever people of different religions live in close proximity to each other, religious sectarianism can often be found in varying forms and degrees. In some areas, religious sectarians (for example Protestant and Catholic Christians) now exist peacefully side-by-side for the most part, although these differences have resulted in violence, death, and outright warfare as recently as the 1990s. Probably the best-known example in recent times were The Troubles.

Catholic-Protestant sectarianism has also been a factor in U.S. presidential campaigns. Prior to John F. Kennedy, only one Catholic (Al Smith) had ever been a major party presidential nominee, and he had been solidly defeated largely because of claims based on his Catholicism. JFK chose to tackle the sectarian issue head-on during the West Virginia primary, but that only sufficed to win him barely enough Protestant votes to eventually win the presidency by one of the narrowest margins ever.[10]

Within Islam, there has been conflict at various periods between Sunnis and Shias; Shi'ites consider Sunnis to be damned, due to their refusal to accept the first Caliph as Ali and accept all following descendants of him as infallible and divinely guided. Many Sunni religious leaders, including those inspired by Wahhabism and other ideologies have declared Shias to be heretics or apostates.[11]

Europe

Long before the Reformation, dating back to the 12th century, there has been sectarian conflict of varying intensity in Ireland. This sectarianism is connected to a degree with nationalism. This has been particularly intense in Northern Ireland since the early 17th century plantation of Ulster under James I, with its religious and denominational sectarian tensions lasting to the present day in some forms. This has translated to parts of Great Britain, most notably Liverpool, and the West Central Scotland, the latter being very close geographically to Northern Ireland, and where some fans of the two best-known football clubs, Celtic (long been affiliated with Catholics) and Rangers (long affiliated with Protestants), indulge in provocative and sectarian behaviour.

Historically, some Catholic countries once persecuted Protestants as heretics. For example, the substantial Protestant population of France (the Huguenots) was expelled from the kingdom in the 1680s following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes. In Spain, the Inquisition sought to root out crypto-Jews but also crypto-Muslims (moriscos); elsewhere the Papal Inquisition held similar goals.

In most places where Protestantism is the majority or "official" religion, there have been examples of Catholics being persecuted. In countries where the Reformation was successful, this often lay in the perception that Catholics retained allegiance to a 'foreign' power (the Papacy or the Vatican), causing them to be regarded with suspicion. Sometimes this mistrust manifested itself in Catholics being subjected to restrictions and discrimination, which itself led to further conflict. For example, before Catholic Emancipation was introduced with the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829, Catholics were forbidden from voting, becoming MP's or buying land in Ireland.

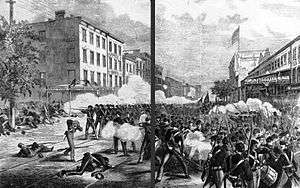

Ireland was deeply scarred by religious sectarianism following the Protestant Reformation as tensions between the native Catholic Irish and Protestant settlers from Britain led to massacres and attempts at ethnic cleaning by both sides during the Irish Rebellion of 1641, Cromwellian conquest of Ireland, Irish Rebellion of 1798 and the Home Rule Crisis of 1912. The invasion of Ireland by English parliamentarian forces under Oliver Cromwell in 1659 was notoriously brutal and witnessed the widespread ethnic cleansing of the native Irish. The failure of the Rebellion of 1798, which sought to unite Protestants and Catholics for an independent Ireland, helped cause more sectarian violence in the island, most infamously the Scullabogue Barn massacre, in which Protestants were burned alive in County Wexford. The British response, which included the public executions of dozens of suspected rebels in Dunlavin and Carnew, along with other violence perpetrated by all sides, ended the hope that Protestants and Catholics could work together for Ireland.

After the Partition of Ireland in 1922, Northern Ireland witnessed decades of intensified conflict, tension, and sporadic violence between the dominant Protestant majority and the Catholic minority, which in 1969 finally erupted into 25 years of violence known as “The Troubles” between Irish Republicans whose goal is a United Ireland and Ulster loyalists who wish for Northern Ireland to remain a part of the United Kingdom. The conflict was primarily fought over the existence of the Northern Irish state rather than religion, though sectarian relations within Northern Ireland fueled the conflict. However, religion is commonly used as a marker to differentiate the two sides of the community. The Catholic minority primarily favour the nationalist, and to some degree, republican, goal of unity with the Republic of Ireland, while the Protestant majority favour Northern Ireland continuing the union with Great Britain.

Northern Ireland has introduced a Private Day of Reflection,[12] since 2007, to mark the transition to a post-[sectarian] conflict society, an initiative of the cross-community Healing through Remembering[13] organisation and research project.

The civil wars in the Balkans which followed the breakup of Yugoslavia in the 1990s have been heavily tinged with sectarianism. Croats and Slovenes have traditionally been Catholic, Serbs and Macedonians Eastern Orthodox, and Bosniaks and most Albanians Muslim. Religious affiliation served as a marker of group identity in this conflict, despite relatively low rates of religious practice and belief among these various groups after decades of communism.

Africa

Over 1,000 Muslims and Christians were killed in the sectarian violence in the Central African Republic in 2013–2014.[14] Nearly 1 million people, a quarter of the population, were displaced.[15]

Australia

Sectarianism in Australia was a historical legacy from the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries, between Catholics of mainly Celtic heritage and Protestants of mainly English descent. It has largely disappeared in the 21st century. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, religious tensions are more centered on Muslim immigrants amid the backdrop of Salafist or Islamist terrorism.

Asia

Japan

For the violent conflict between Buddhist sects in Japan, see Japanese Buddhism.

Pakistan

Pakistan, one of the largest Muslim countries the world, has seen serious Shia-Sunni sectarian violence.[16] Almost 80 - 85% of Pakistan's Muslim population is Sunni, and another 10 - 20% are Shia.[17][18] However, this Shia minority forms the second largest Shia population of any country, larger than the Shia majority in Iraq.

In the last two decades, as many as 4,000 people are estimated to have died in sectarian fighting in Pakistan, 300 in 2006.[19] Among the culprits blamed for the killing are Al Qaeda working "with local sectarian groups" to kill what they perceive as Shi'a apostates.[19]

Sri Lanka

Most Muslims in Sri Lanka are Sunnis. There are a few Shia Muslims too from the relatively small trading community of Bohras. Divisiveness is not a new phenomenon to Beruwala. Sunni Muslims in the Kalutara district are split in two different sub groups. One group, known as the Alaviya sect, historically holds its annual feast at the Ketchimalai mosque located on the palm-fringed promontory adjoining the fisheries harbour in Beruwala.

It is a microcosm of the Muslim identity in many ways. The Galle Road that hugs the coast from Colombo veers inland just ahead of the town and forms the divide. On the left of the road lies China Fort, the area where some of the wealthiest among Sri Lankans Muslims live. The palatial houses with all modern conveniences could outdo if not equal those in the Colombo 7 sector. Most of the wealthy Muslims, gem dealers, even have a home in the capital, not to mention property.

Strict Wahabis believe that all those who do not practise their form of religion are heathens and enemies. There are others who say Wahabism's rigidity has led it to misinterpret and distort Islam, pointing to the Taliban as well as Osama bin Laden. What has caused concern in intelligence and security circles is the manifestation of this new phenomenon in Beruwala. It had earlier seen its emergence in the east.

Middle East

Ottoman Empire

Sultan Selim the Grim, regarding the Shia Qizilbash as heretics, reportedly proclaimed that "the killing of one Shiite had as much otherworldly reward as killing 70 Christians."[20] In 1511, a pro-Shia revolt known as Şahkulu Rebellion was brutally suppressed by the Ottomans: 40,000 were massacred on the order of the sultan.[21]

Iran

Overview

Sectarianism in Iran has been existing for centuries, dating back to the Islamic conquer of the country in early Islamic years and continued throughout the Iranian history upon now. During the Safavid Dynasty's reign sectarianism started to play an important role in shaping the path of the country.[22] During the Safavid rule between 1501 and 1722, Shiism started to evolve and became established as the official state religion, leading to the creation of the first religiously legitimate government since the occultation of the Twelfth imam.[23] This pattern of sectarianism prevailed throughout the Iranian history. The approach that sectarianism has taken after the Iranian 1979 revolution is shifted compared to the earlier periods. Never before the Iranian 1979 revolution did the Shiite leadership gain as much authority.[24] Due to this change, the sectarian timeline in Iran can be divided in pre- and post-Iranian 1979 revolution where the religious leadership changed course.

Pre-1979 Revolution

Shiism has been an important factor in shaping the politics, culture and religion within Iran, long before the Iranian 1979 revolution.[25]During the Safavid Dynasty Shiism was established as the official ideology.[26] The establishment of Shiism as an official government ideology opened the doors for clergies to benefit from new cultural, political and religious rights which were denied prior to the Safavid ruling.[27] During the Safavid Dynasty Shiism was established as the official ideology.[28] The Safavid rule allowed greater freedom for religious leaders. By establishing Shiism as the state religion, they legitimised the religious authority. After this power establishment, religious leaders started to play a crucial role within the political system but remained socially and economically independent.[29] The monarchial power balance during the Safavid ere changed every few years, resulting in a changing limit of power of the clergies. The tensions concerning power relations of the religious authorities and the ruling power eventually played a pivotal role in the 1906 constitutional revolution which limited the power of the monarch, and increased the power of religious leaders.[30] The 1906 constitutional revolution involved both constitutionalist and anti-constitutionalist clergy leaders. Individuals such as Sayyid Jamal al-Din Va'iz were constitutionalist clergies whereas other clergies such as Mohammed Kazem Yazdi were considered anti-constitutionalist. The establishment of a Shiite government during the Safavid rule resulted in the increase of power within this religious sect. The religious power establishment increased throughout the years and resulted in fundamental changes within the Iranian society in the twentieth century, eventually leading to the establishment of the Shiite Islamic Republic of Iran in 1979.

Post-1979 Revolution: Islamic Republic of Iran

The Iranian 1979 revolution led to the overthrow of the Pahlavi dynasty and the establishment of the Islamic Government of Iran. The governing body of Iran displays clear elements of sectarianism which are visible within different layers of its system. The 1979 revolution led to changes in political system, leading to the establishment of a bureaucratic clergy-regime which has created its own interpretation of the Shia sect in Iran.[31]Religious differentiation is often used by authoritarian regimes to express hostility towards other groups such as ethnic minorities and political opponents.[32] Authoritarian regimes can use religion as a weapon to create an "us and them" paradigm. This leads to hostility amongst the involved parties and takes place internally but also externally. A valid example is the suppression of religious minorities like the Sunnis and Baha-ís. With the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran sectarian discourses arose in the Middle-East as the Iranian religious regime has attempted and in some cases succeeded to spread its religious and political ideas in the region. These sectarian labeled issues are politically charged. The most notable Religious leaders in Iran are named Supreme-leaders. Their role has proved to be pivotal in the evolvement of sectarianism within the country and in the region. The following part discusses Iran's supreme-leadership in further detail.

Ruhollah Khomeini and Ali Khamenei

During the Iran-Iraq war, Iran's first supreme-leader, Ayatollah Khomeini called for the participation of all Iranians in the war. His usage of Shia martyrdom led to the creation of a national consensus.[33] In the early aftermath of the Iranian 1979 revolution, Khomeini started to evolve a sectarian tone in his speeches. His focus on Shiism and Shia Islam grew which was also implemented within the changing policies of the country. In one of his speeches Khomeini quoted: "the Path to Jerusalem passes through Karbala." His phrase lead to many different interpretations, leading to turmoil in the region but also within the country.[34] From a religious historic viewpoint, Karbala and Najaf which are both situated in Iraq, serve as important sites for Shia Muslims around the world. By mentioning these two cities, Khomeini led to the creation of Shia expansionism.[35] Khomeini's war with the Iraqi Bath Regime had many underlying reasons and sectarianism can be considered as one of the main reasons. The tensions between Iran and Iraq are of course not only sectarian related, but religion is often a weapon used by the Iranian regime to justify its actions. Khomeini's words also resonated in other Arab countries who had been fighting for Palestinian liberation against Israel. By naming Jerusalem, Khomeini expressed his desire for liberating Palestine from the hands of what he later often has named "the enemy of Islam." Iran has supported rebellious groups throughout the region. Its support for Hamas and Hezbollah has resulted in international condemnation[36]. This desire for Shia expansionism did not disappear after Khomeini's death. It can even be argued that sectarian tone within the Islamic Republic of Iran has grown since then. The Friday prayers held in Tehran by Ali Khamenei can be seen as a proof of growing sectarian tone within the regime. Khamenei's speeches are extremely political and sectarian.[37] He often mentions extreme wishes such as the removal of Israel from the world map and fatwas directed towards those opposing the regime.[38]

Regional tensions and Iran's role

The political approach that the Islamic Republic of Iran has taken in the previous decades has led to the increase of tensions in the region. World leaders from around the world have criticised the political ambitions of Iran and have condemned its involvement and support for opposition groups such as Hezbollah.[39] By using religion as an instrument, Iran has expanded its authority to neighbouring countries.[40] An important figure in this process of power and ideology expansion was the major general of Iran's Quds Force, the foreign arm of the IRGC, Qasem Soleimani.[41] Soleimani was assassinated in Iraq by an American drone in January 2020 leading to an increase of tension between the United States of America and Iran.[42] Soleimani was responsible for strengthening Iran's ties with foreign powers such as Hezbollah in Lebanon, Syria's al-Assad and Shia militia groups in Iraq.[43] Soleimani was seen as the number-one commander of Iran's foreign troops and played a crucial role in the spread of Iran's ideology in the region. According to President Donald Trump, Soleimani was the worlds most wanted terrorist and had to be assassinated in order to bring more peace to the Middle-East region but also the rest of the world.[44] Soleimani's death has not ended Iran's political, sectarian and regional ambitions. Iran remains a key power in expending ideologies to its neighbouring countries. Shiism is used by the regime to justify its actions. But it can be concluded that Iran's usage of religion is an excuse to spread its political power regionally.[45]

Iraq

Sunni Iraqi insurgency and foreign Sunni terrorist organizations who came to Iraq after the fall of Saddam Hussein have targeted Shia civilians in sectarian attacks. Following the civil war, the Sunnis have complained of discrimination by Iraq's Shia majority governments, which is bolstered by the news that Sunni detainees were allegedly discovered to have been tortured in a compound used by government forces on November 15, 2005.[46] This sectarianism has fueled a giant level of emigration and internal displacement.

The Shia majority oppression by the Sunni minority has a long history in Iraq, after the fall of the Ottoman Empire, the British imposed upon Iraq a rule of Sunni Hashemite monarchy that suppressed various uprisings against its rule by the Christian Assyrians, Kurds, Yazidis and Shi'ites. After the monarchy was overthrown, Iraq was ruled by the de jure secular Baathist Party, while de facto a minority Sunni absolute rule that discriminated against and persecuted the Shia majority.

Syria

Although sectarianism has been described as one of the characteristic features of the Syrian civil war, the narrative of sectarianism already had its origins in Syria’s past.

Ottoman rule

The hostilities that took place in 1850 in Aleppo and subsequently in 1860 in Damascus, had many causes and reflected long-standing tensions. However, scholars have claimed that the eruptions of violence can also be partly attributed to the modernizing reforms, the Tanzimat, taking place within the Ottoman Empire, who had been ruling Syria since 1516.[47][48] The Tanzimat bring about equality between Muslims and non-Muslims living in the Ottoman Empire. This caused the non-Muslims to gain privileges and influence.[49] In addition to this growing position of non-Muslims through the Tanzimat reforms, the influence of European powers also came mainly to the benefit of the Christians, Druzes and Jews. In the silk trade business, European powers formed ties with local sects. They usually opted for a sect that adhered to a religion similar to the one in their home countries, thus not Muslims.[50] These developments caused new social classes to emerge, consisting of mainly Christians, Druzes and Jews. These social classes stripped the previously existing Muslim classes of their privileges. The involvement of another foreign power, though this time non-European, also had its influence on communal relations in Syria. Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt ruled Syria between 1831 and 1840. His divide-and-rule strategy contributed to the hostilities between the Druze and Maronite community, by arming the Maronite Christians. However, it is noteworthy to mention that different sects did not fight the others out of religious motives, nor did Ibrahim Pasha aim to disrupt society among communal lines.[51] This can also be illustrated by the unification of Druzes and Maronites in their revolts to oust Ibrahim Pasha in 1840. This goes to show the fluidity of communal alliances and animosities and the different, at times non-religious, reasons that may underline sectarianism.

After Ottoman rule

Before the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the French Mandate in Syria, the Syrian territory had already witnessed massacres on the Maronite Christians, other Christians, Alawites, Shias and Ismailiyas, which had resulted in distrustful sentiments between the members of different sects.[52] In an attempt to protect the minority communities against the majority Sunni population, France, with the command of Henri Gouraud, created five states for the following sects: Armenians, Alawites, Druzes, Maronite Christians and Sunni Muslims.[53] This focus on minorities was new and part of a divide-and-rule strategy of the French, which enhanced and politicized differences between sects.[54] The restructuring by the French caused the Alawite community to advance itself from their marginalized position. In addition to that, the Alawites were also able to obtain a position of power through granting top level positions to family members of the ruling clan or other tribal allies of the Alawite community.[55]

During the period 1961–1980, Syria was not necessarily exclusively ruled by the Alawite sect, but due to efforts of the Sunni Muslim extremist opponents of the Ba’th regime in Syria, it was perceived as such. The Ba’ath regime was being dominated by the Alawite community, as well as were other institutions of power.[56] As a result of this, the regime was considered to be sectarian, which caused the Alawite community to cluster together, as they feared for their position.[56] This period is actually contradictory as Hafez al-Assad tried to create a Syrian Arab nationalism, but the regime was still regarded as sectarian and sectarian identities were reproduced and politicized.[57]

Sectarian tensions that later gave rise to the Syrian civil war, had already appeared in society due to events preceding 1970. For example, President Hafez al-Assad’s involvement in the Lebanese civil war by giving political aid to Maronite Christians in Lebanon. This was viewed by many Sunny Muslims as an act of treason, which made them link al-Assad’s actions to his Alawite identity.[58] The Muslim Brothers, a part of the Sunni Muslims, used those tensions towards the Alawites as a tool to boost their political agenda and plans.[58] Several assassinations were carried out by the Muslim Brothers, mostly against Alawites, but also against some Sunni Muslims. The failed assassination attempt on President Hafez al-Assad is arguably the most well-known.[59] Part of the animosity between the Alawites and the Sunni Islamists of the Muslim Brothers is due to the secularization of Syria, which the later holds the Alawites in power to be responsible for.

Syrian Civil War

As of 2015, the majority of the Syrian population consisted of Sunni Muslims, namely two-thirds of the population, which can be found throughout the country. The Alawites are the second largest group, which make up around 10 percent of the population.[60] This makes them a ruling minority. The Alawites were originally settled in the highlands of Northwest Syria, but since the twentieth century have spread to places like Latakia, Homs and Damascus.[61] Other groups that can be found in Syria are Christians, among which the Maronite Christians, Druzes and Twelver Shias. Although sectarian identities played a role in the unfolding of events of the Syrian Civil War, the importance of tribal and kinship relationships should not be underestimated, as they can be used to obtain and maintain power and loyalty.[55]

At the start of the protests against President Basher al-Assad in March 2011, there was no sectarian nature or approach involved. The opposition had national, inclusive goals and spoke in the name of a collective Syria, although the protesters being mainly Sunni Muslims.[62] This changed after the protests and the following civil war began to be portrayed in sectarian terms by the regime, as a result of which people started to mobilize along ethnic lines.[63] However, this does not mean that the conflict is solely or primarily a sectarian conflict, as there were also socio-economic factors at play. These socio-economic factors were mainly the result of Basher al-Assad's mismanaged economic restructuring.[64] The conflict has therefore been described as being semi-sectarian, making sectarianism a factor at play in the civil war, but certainly does not stand alone in causing the war and has varied in importance throughout time and place.[65]

In addition to local forces, the role of external actors in the conflict in general as well as the sectarian aspect of the conflict should not be overlooked. Although foreign regimes were first in support of the Free Syrian Army, they eventually ended up supporting sectarian militias with money and arms. However, it has to be said that their sectarian nature did not only attract these flows of support, but they also adopted a more sectarian and Islamic appearance in order to attract this support.[66]

Yemen

Introduction

In Yemen, there have been many clashes between Salafis and Shia Houthis.[67] According to The Washington Post, "In today’s Middle East, activated sectarianism affects the political cost of alliances, making them easier between co-religionists. That helps explain why Sunni-majority states are lining up against Iran, Iraq and Hezbollah over Yemen."[68]

Historically, divisions in Yemen along religious lines (sects) are less intense than those in Pakistan, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and Bahrain.[69][70][71][72] Most political forces in Yemen are primarily characterized by regional interests and not by religious sectarianism.[69][71] Regional interests are, for example, the north’s proximity to the Hejaz, the south’s coast along the Indian ocean trade route, and the southeast's oil and gas fields.[71][73] Yemen’s northern population consists for a substantial part of Zaydis, and its southern population predominantly of Shafi’is.[71] Hadhramaut in Yemen’s southeast has a distinct Sufi Ba’Alawi profile.[71]

Ottoman era, 1849–1918

Sectarianism reached the region once known as Arabia Felix with the 1911 Treaty of Daan.[74][75] It divided the Yemen Vilayet into an Ottoman controlled section and an Ottoman-Zaydi controlled section.[74][75] The former dominated by Sunni Islam and the latter by Zaydi-Shia Islam, thus dividing the Yemen Vilayet along Islamic sectarian lines.[74][75] Yahya Muhammad Hamid ed-Din became the ruler of the Zaidi community within this Ottoman entity.[74][76] Before the agreement, inter-communal battles between Shafi’is and Zaydis never occurred in the Yemen Vilayet.[77][75] After the agreement, sectarian strife still did not surface between religious communities.[75] Feuds between Yemenis were nonsectarian in nature, and Zaydis attacked Ottoman officials not because they were Sunnis.[75]

Following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the divide between Shafi’is and Zaydis changed with the establishment of the Kingdom of Yemen.[74][76] Shafi’i scholars were compelled to accept the supreme authority of Yahya Muhammad Hamid ed-Din, and the army “institutionalized the supremacy of the Zaydi tribesman over the Shafi’is”.[74][76]

Unification period, 1918–1990

Before the 1990 Yemeni unification, the region had never been united as one country.[78][79] In order to create unity and overcome sectarianism, the myth of Qahtanite was used as a nationalist narrative.[80] Although not all ethnic groups of Yemen fit in this narrative, such as the Al-Akhdam and the Teimanim.[80][81] The latter established a Jewish kingdom in ancient Yemen, the only one ever created outside Palestine.[82] A massacre of Christians, executed by the Jewish king Dhu Nuwas, eventually led to the fall of the Homerite Kingdom.[83][82] In modern times, the establishment of the Jewish state resulted in the 1947 Aden riots, after which most Teimanim left the country during Operation Magic Carpet.[81]

Conflicting geopolitical interests surfaced during the North Yemen Civil War (1962-1970).[79] Wahhabist Saudi Arabia and other Arab monarchies supported Muhammad al-Badr, the deposed Zaydi imam of the Kingdom of Yemen.[78][79][84] His adversary, Abdullah al-Sallal, received support from Egypt and other Arab republics.[78][79][84] Both international backings were not based on religious sectarian affiliation.[78][79][84][85] In Yemen however, President Abdullah al-Sallal (a Zaydi) sidelined his vice-president Abdurrahman al-Baidani (a Shaffi'i) for not being a member of the Zaydi sect.[83][82] Shaffi'i officials of North Yemen also lobbied for "the establishment of a separate Shaffi'i state in Lower Yemen" in this period.[83]

Contemporary Sunni-Shia rivalry

According to Lisa Wedeen, the perceived sectarian rivalry between Sunnis and Shias in the Muslim world is not the same as Yemen’s sectarian rivalry between Salafists and Houthis.[86] Not all supporters of Houthi’s Ansar Allah movement are Shia, and not all Zaydis are Houthis.[87][88][89] Although most Houthis are followers of Shia’s Zaydi branch, most Shias in the world are from the Twelver branch. Yemen is geographically not in proximity of the so-called Shia Crescent. To link Hezbollah and Iran, whose subjects are overwhelmingly Twelver Shias, organically with Houthis is exploited for political purposes.[90][88][89][91][92] Saudi Arabia emphasized an alleged military support of Iran for the Houthis during Operation Scorched Earth.[93][88][94] The slogan of the Houthi movement is 'Death to America, death to Israel, a curse upon the Jews'. This is a trope of Iran and Hezbollah, so the Houthis seem to have no qualms about a perceived association with them.[87][90][88][94]

Tribes and political movements

Tribal culture in the southern regions has virtually disappeared through policies of the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen.[95][96] However, Yemen's northern part is still home to the powerful tribal confederations of Bakil and Hashid.[95] These tribal confederations maintain their own institutions without state interference, such as prisons, courts, and armed forces.[95] Unlike the Bakils, the Hashids adopted Salafist tenets, and during the Sa’dah War (2004-2015) sectarian tensions materialized.[95] Yemen’s Salafists attacked the Zaydi Mosque of Razih in Sa’dah and destroyed tombs of Zaydi imams across Yemen.[97][95][98] In turn, Houthis attacked Yemen’s main Salafist center of Muqbil bin Hadi al-Wadi'I during the Siege of Dammaj.[97][95][99] Houthis also attacked the Salafist Bin Salman Mosque and threatened various Teimanim families.[100][101]

Members of Hashid’s elite founded the Sunni Islamist party Al-Islah and, as a counterpart, Hizb al-Haqq was founded by Zaydis with the support of Bakil's elite.[95][99][101] Violent non-state actors Al-Qaeda, Ansar al-Sharia and Daesh, particularly active in southern cities like Mukalla, fuel sectarian tendencies with their animosity towards Yemen's Isma'ilis, Zaydis, and others.[102][95][103][104][105] An assassination attempt in 1995 on Hosni Mubarak, executed by Yemen’s Islamists, damaged the country's international reputation.[100] The war on terror further strengthened Salafist-jihadist groups impact on Yemen’s politics.[95][100][98] The 2000 USS Cole bombing resulted in US military operations on Yemen's soil.[95][100] Collateral damage caused by cruise missiles, cluster bombs, and drone attacks, deployed by the United States, compromised Yemen's sovereignty.[95][100][99]

Ali Abdullah Saleh's reign

Ali Abdullah Saleh is a Zaydi from the Hashid’s Sanhan clan and founder of the nationalist party General People's Congress.[106] During his decades long reign as head of state, he used Sa'dah's Salafist's ideological dissemination against Zaydi's Islamic revival advocacy.[107][108] In addition, the Armed Forces of Yemen used Salafists as mercenaries to fight against Houthis.[106] Though, Ali Abdullah Saleh also used Houthis as a political counterweight to Yemen's Muslim Brotherhood.[109][108] Due to the Houthis persistent opposition to the central government, Upper Yemen was economically marginalized by the state.[109][108] This policy of divide and rule executed by Ali Abdullah Saleh worsened Yemen's social cohesion and nourished sectarian persuasions within Yemen’s society.[109][107][108]

Following the Arab Spring and the Yemeni Revolution, Ali Abdullah Saleh was forced to step down as president in 2012.[106][110] Subsequently, a complex and violent power struggle broke out between three national alliances: (1) Ali Abdullah Saleh, his political party General People's Congress, and the Houthis; (2) Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar, supported by the political party Al-Islah; (3) Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi, supported by the Joint Meeting Parties.[111][112][113] According to Ibrahim Fraihat, “Yemen’s conflict has never been about sectarianism, as the Houthis were originally motivated by economic and political grievances. However, in 2014, the regional context substantially changed”.[112] The Houthi takeover in 2014-2015 provoked a Saudi-led intervention, strengthening the sectarian dimension of the conflict.[114][112] Hezbollah's Hassan Nasrallah heavily criticized the Saudi intervention, bolstering the regional Sunni-Shia geopolitical dynamic behind it.[112]

Saudi Arabia

The Saudi government has often been viewed as an active oppressor of Shia Muslims because of the funding of the Wahabbi ideology which denounces the Shia faith.[115] Prince Bandar bin Sultan, Saudi ambassador to the United States, stated: "The time is not far off in the Middle East when it will be literally 'God help the Shia'. More than a billion Sunnis have simply had enough of them."[116]

According to The New York Times, "The documents from Saudi Arabia’s Foreign Ministry illustrate a near obsession with Iran, with diplomats in Africa, Asia and Europe monitoring Iranian activities in minute detail and top government agencies plotting moves to limit the spread of Shiite Islam."[117]

On March 25, 2015, Saudi Arabia, spearheading a coalition of Sunni Muslim states,[118] started a military intervention in Yemen against the Shia Houthis.[119]

As of 2015, Saudi Arabia is openly supporting the Army of Conquest,[120][121] an umbrella group of anti-government forces fighting in the Syrian Civil War that reportedly includes an al-Qaeda linked al-Nusra Front and another Salafi coalition known as Ahrar al-Sham.[122]

In January 2016, Saudi Arabia executed the prominent Saudi Shia cleric Nimr al-Nimr.[123]

Lebanon

Overview

Sectarianism in Lebanon has been formalized and legalized within state and non-state institutions and is inscribed in its constitution. The foundations of sectarianism in Lebanon date back to the mid-19th century during Ottoman rule. It was subsequently reinforced with the creation of the Republic of Lebanon in 1920 and its 1926 constitution, and in the National Pact of 1943. In 1990, with the Taif Agreement, the constitution was revised but did not structurally change aspects relating to political sectarianism.[124] The dynamic nature of sectarianism in Lebanon has prompted some historians and authors to refer to it as "the sectarian state par excellence" because it is an amalgam of religious communities and their myriad sub-divisions, with a constitutional and political order to match.[125]

Historical background

According to various historians, sectarianism in Lebanon is not simply an inherent phenomena between the various religious communities there. Rather, historians have argued that the origins of sectarianism lay at the "intersection of nineteenth-century European colonialism and Ottoman modernization".[126] The symbiosis of Ottoman modernization (through a variety of reforms) and indigenous traditions and practices became paramount in reshaping the political self-definition of each community along religious lines. The Ottoman reform movement launched in 1839 and the growing European presence in the Middle East subsequently led to the disintegration of the traditional Lebanese social order based on a hierarchy that bridged religious differences. Nineteenth-century Mount Lebanon was host to competing armies and ideologies and for "totally contradictory interpretations of the meaning of reform" (i.e. Ottoman or European).[127] This fluidity over reform created the necessary conditions for sectarianism to rise as a "reflection of fractured identities" pulled between enticements and coercions of Ottoman and European power.[126] As such, the Lebanese encounter with European colonization altered the meaning of religion in the multi-confessional society because it "emphasized sectarian identity as the only viable marker of political reform and the only authentic basis for political claims."[128] As such, during both Ottoman rule and later during the French Mandate, religious identities were deliberately mobilized for political and social reasons.

The Lebanese political system

Lebanon gained independence on 22 November 1943. Shortly thereafter, the National Pact was agreed upon and established the political foundations of modern Lebanon and laid the foundations of a sectarian power-sharing system (also known as confessionalism) based on the 1932 census.[129] The 1932 census is the only official census conducted in Lebanon: with a total population of 1,046,164 persons, Maronites made up 33.57%, Sunnis made up 18.57% and Shiites made up 15.92% (with several other denominations making up the remainder). The National Pact served to reinforce the sectarian system that had begun under the French Mandate, by formalizing the confessional distribution of the highest public offices and top administrative ranks according to the proportional distribution of the dominant sects within the population.[130] Because the census showed a slight Christian dominance over Muslims, seats in the Chamber of Deputies (parliament) were distributed by a six-to-five ratio favoring Christians over Muslims. This ratio was to be applied to all highest-level public and administrative offices, such as ministers and directors. Furthermore, it was agreed that the President of the Republic would be a Maronite Christian; the Premier of the Council of Ministers would be a Sunni Muslim; the President of the National Assembly would be a Shiite Muslim; and the Deputy Speaker of Parliament a Greek Orthodox Christian.[129]

The Lebanese Civil War, 1975–1990

During the three decades following independence from the French Mandate, "various internal tensions inherent to the Lebanese system and multiple regional developments collectively contributed to the breakdown of governmental authority and the outbreak of civil strife in 1975”.[129] According to Makdisi, sectarianism reached its peak during the civil war that lasted from 1975–1990.[131] The militia politics that gripped Lebanon during the civil war represents another form of popular mobilization along sectarian lines against the elite-dominated Lebanese state.[126]

Christians began setting up armed militias what they “saw as an attempt by the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) to seize Lebanon – those militias would be united under the Lebanese Forces umbrella in 1976”.[132] Lebanese Sunni groups splintered into armed factions as well, competing against one another and against the Christian militias. The beginning of the Lebanese Civil War dates to 1975, when a Maronite militia opened fire on a bus full of civilians in response to an assassination attempt of a Maronite leader by PLO-affiliated Muslims.[132] On May 31, seven weeks after fighting began between militias, Beirut witnessed its first sectarian massacre in which "unarmed civilians were killed simply on the grounds of their religion."[133]

Syria entered the conflict in June 1976, in order to avoid a PLO takeover of Lebanon – Syria's entry into the war resulted in a de facto division of the country into zones controlled by Syria, the PLO, and Maronite militias.[132] Shi’a militias were also created, including the formation of Amal in the late 1970s and later when some Amal militants decided to create a more religious Shi’a militia known as Hezbollah (Party of God).

The Lebanese Civil War became a regional dilemma when Israel invaded in 1982 with two avowed aims: destroy the PLO military infrastructure and secure its northern frontier. In March 1989, Prime Minister (and Acting President) General Michel Aoun launched a “liberation war” against the Syrian army with the backing of the PLO and Iraqi president Saddam Hussein. In doing so, General Aoun internationalized the Lebanese crisis by “emphasized the destructive role of the Syrian army in the country”.[132] His decision resulted in multilateral negotiations as well as efforts to strengthen the role of the UN. By 1983, what had begun as an internal war between Lebanese factions had become a regional conflict that drew in Syria, Israel, Iran, Europe and the United States directly - with Iraq, Libya, Saudi Arabia, and the Soviet Union involved indirectly by providing financial support and weaponry to different militias.[134]

After fifteen years of war, at least 100,000 Lebanese were dead, tens of thousands had emigrated abroad, and an estimated 900,000 civilians were internally displaced.[132]

The Taif Agreement

After twenty-two days of discussions and negotiations, the surviving members of the 1972 parliament reached an agreement to end the Civil War on October 22, 1989. The Taif Agreement reconfigured the political power-sharing formula that formed that basis of government in Lebanon under the National Pact of 1943.[135] As noted by Eugene Rogan, "the terms of Lebanon's political re-construction, enshrined in the Taif [Agreement], preserved many of the elements of the confessional system set up in the National Pact but modified the structure to reflect the demographic realities of modern Lebanon."[136] As such, several key provisions of the National Pact were changed including: it relocated most presidential powers in favor of Parliament and the Council of Ministers and, as such, the Maronite Christian President lost most of his executive powers and only retained symbolic roles; it redistributed important public offices, including those of Parliament, Council of Ministers, general directors, and grade-one posts evenly between Muslims and Christians thereby upsetting the traditional ratio of six to five that favored Christians under the National Pact; it “recognized the chronic instability of confessionalism and called for devising a national strategy for its political demise. It required the formation of a national committee to examine ways to achieve deconfessionalization and the formation of a non-confessional Parliament," which has not yet been implemented to date[129] and it required the disarmament of all Lebanese militias; however, Hezbollah was allowed to retain its militant wing as a “resistance force” in recognition of its fight against Israel in the South.[129]

Spillover from the Syrian conflict

The Syrian conflict which began in 2011 when clashes began between the Assad government and opposition forces has had a profound effect on sectarian dynamics within Lebanon. In November 2013, the United States Institute of Peace published a Peace Brief in which Joseph Bahout assesses how the Syrian crisis has influenced Lebanon's sectarian and political dynamics. Bahout argues that the Syrian turmoil is intensifying Sunni-Shia tensions on two levels: “symbolic and identity-based on the one hand, and geopolitical or interest based, on the other hand." Syria's conflict has profoundly changed mechanisms of inter-sectarian mobilization in Lebanon: interest-based and “political” modes of mobilization are being transformed into identity-based and “religious” modes. Bahout notes that this shift is likely due to how these communities are increasingly perceiving themselves as defending not only their share of resources and power, but also their very survival. As the conflict grows more intense, the more the sectarian competition is internalized and viewed as a zero-sum game. Perceptions of existential threat exist among both the Shiite and Sunni communities throughout Lebanon: the continuation of the Syrian conflict will likely increase these perceptions over time and cause terrorism.[124]

There are notable divisions within the Lebanese community along sectarian lines regarding the Syrian Civil War. The Shi'ite militant and political organization Hezbollah and its supporters back the Assad government, while many of the country's Sunni communities back the opposition forces. These tensions have played out in clashes between Sunnis and Shi'ites within Lebanon, resulting in clashes and deaths. For instance, clashes in the northern city of Tripoli, Lebanon left three dead when fighting broke out between Assad supporters and opponents.[137]

The largest concentration of Syrian refugees, close to one million people as of April 2014, can be found in Lebanon and has resulted in a population increase by about a quarter. According to the United Nations, the massive influx of refugees threatens to upset the “already fragile demographic balance between Shi’ites, Sunnis, Druze, and Christians.”[138] The Lebanese government faces major challenges for handling the refugee influx, which has strained public infrastructure as Syrians seek housing, food, and healthcare at a time of economic slowdown in Lebanon.

For background on Syria-Lebanon relations, see Lebanon-Syria relations.

See also

References

- Roberts, Keith Daniel (2017). Liverpool Sectarianism: The Rise and Demise. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-78694-010-0.

- Hashemi, Nader, and Danny Postel. "Introduction: The Sectarianization Thesis." In Sectarianization: Mapping the New Politics of the Middle East, edited by Nader Hashemi and Danny Postel. New York: Oxford University Press, 2017. pp. 3, 5, 6, 10. ISBN 978-0-19-937-726-8.

- Weiss, Max. In the Shadow of Sectarianism : Law, Shi`ism, and the Making of Modern Lebanon. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010. pp. 3, 4, 9–11, 11–128, 127, 129, 229. ISBN 978-0-674-05298-7.

- Hashemi, Nader. The West's "intellectually lazy" obsession with sectarianism. Interview by Emran Feroz. Qantara, October 17, 2018.

- Makdisi, Ussama Samir. The Culture of Sectarianism: Community, History, and Violence in Nineteenth-Century Ottoman Lebanon. California: University of California Press, 2000. p. 2. ISBN 0-520-21845-0

- Makdisi, Ussama Samir. "Understanding Sectarianism." ISIM Newsletter 8, no.1 (2001), p. 19.

- Cammett, Melani. Compassionate Communalism: Welfare and Sectarianism in Lebanon. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2014. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-8014-5232-1.

- Henley, Alexander D. M. "Review of Max Weiss, In the Shadow of Sectarianism: Law, Shiʿism and the Making of Modern Lebanon." New Middle Eastern Studies, 1 (2011). p. 2

- Ellis, Kail C. "Epilogue." In Secular Nationalism and Citizenship in Muslim Countries: Arab Christians in Muslim Countries, edited by Kail C. Ellis. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018. p. 211. ISBN 978-3-319-71203-1.

- "John F. Kennedy and Religion". Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- "Lahore bomb raises sectarian questions". BBC News. January 10, 2008. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- "HTR - Day of Reflection - Home". Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- "Healing Through Remembering". Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- "Central African Republic: Ethnic cleansing and sectarian killings". Amnesty International. February 12, 2014.

- "Eight dead in Central African Republic capital, rebel leaders flee city". Reuters. January 26, 2014.

- Bhattacharya, Sanchita (2019-06-30). "Pakistan: Sectarian War Scourging an Entire Nation". Liberal Studies. 4 (1): 87–105. ISSN 2688-9374.

- "Pakistan - International Religious Freedom Report 2008". United States Department of State. Retrieved 2013-04-19.

- "Pakistan, Islam in". Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2013-04-19.

Approximately 97 percent of Pakistanis are Muslim. The majority are Sunnis following the Hanafi school of Islamic law. Between 10 and 15 percent are Shiis, mostly Twelvers.

- The Christian Science Monitor. "Shiite-Sunni conflict rises in Pakistan". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- Jalāl Āl Aḥmad (1982). Plagued by the West. Translated by Paul Sprachman. Center for Iranian Studies, Columbia University. ISBN 978-0-88206-047-7.

- H.A.R. Gibb & H. Bowen, "Islamic society and the West", i/2, Oxford, 1957, p. 189

- Khalaji, Mehdi (September 1, 2001). "Iran's Regime of Religion". Journal of International Affairs. 65 (1): 131.

- Khalaji, Mehdi (September 1, 2001). "Iran's Regime of Religion". Journal of International Affairs. 65 (1): 134.

- Mishal, Shaul (March 5, 2015). Understanding Shiite Leadership: the Art of the Middle Ground in Iran and Lebanon. Cambridge University Press. p. 43. ISBN 1107632676.

- Khalaji, Mehdi (September 1, 2001). "Iran's Regime of Religion". Journal of International Affairs. 65 (1): 131.

- Khalaji, Mehdi (September 1, 2001). "Iran's Regime of Religion". Journal of International Affairs. 65 (1): 131.

- Khalaji, Mehdi (September 1, 2001). "Iran's Regime of Religion". Journal of International Affairs. 65 (1): 131.

- Khalaji, Mehdi (September 1, 2001). "Iran's Regime of Religion". Journal of International Affairs. 65 (1): 131.

- Abisaab, Rula. Converting Persia: religion and power in the Safavid Empire. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 186064970X.

- Bayat, Mangol. Iran's first revolution : Shi'ism and the constitutional revolution of 1905-1909. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506822-X.

- Khalaji, Mehdi (September 1, 2001). "Iran's Regime of Religion". Journal of International Affairs. 65 (1): 131.

- Grabowski, Wojciech (2017). "Sectarianism as a Factor Shaping Persian Gulf Security". International Studies. 52 (1–4): 1. doi:10.1177/0020881717715550.

- Abedin, Mahan (July 15, 2015). Iran Resurgent: The Rise and Rise of the Shia State. C. Hurst and Company (Publishers) Limited.

- Abedin, Mahan (July 15, 2015). Iran Resurgent: The Rise and Rise of the Shia State. C. Hurst and Company (Publishers) Limited. p. 24.

- Abedin, Mahan (July 15, 2015). Iran Resurgent : The Rise and Rise of the Shia State. C. Hurst and Company (Publishers) Limited. p. 27.

- "Profile: Lebanon's Hezbollah". BBC News. 15 March 2016.

- "Khamenei: Iran not calling for elimination of Jews, wants non-sectarian Israel". Reuters. November 15, 2019. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- Pileggi, Tamar. "Khamenei: Israel a 'cancerous tumor' that 'must be eradicated'". www.timesofisrael.com.

- Phillips, Christopher (October 25, 2016). The battle for Syria: international rivalry in the new Middle East. Yale University Press. p. 158. ISBN 9780300217179.

- Phillips, Christopher (October 25, 2016). The battle for Syria : international rivalry in the new Middle East. Yale University Press. p. 158. ISBN 9780300217179.

- "Who was Qassem Soleimani, Iran's IRGC's Quds Force leader?". www.aljazeera.com.

- "Top Iranian general killed by US in Iraq". BBC News. 3 January 2020.

- "Top Iranian general killed by US in Iraq". BBC News. 3 January 2020.

- "Remarks by President Trump on the Killing of Qasem Soleimani". The White House.

- "Iran's Use of Religion as a Tool in its Foreign Policy". American Iranian Council.

- "Iraqi Sunnis demand abuse inquiry". BBC News. November 16, 2005. Retrieved 2007-05-12.

- Sahner, Christian C. (2014). Among the Ruins: Syria Past and Present. London: Hurst & Company. p. 99. ISBN 9781849044004.

- Phillips, Christopher (1 February 2015). "Sectarianism and Conflict in Syria". Third World Quarterly. 36(2): 364 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- Fawaz, Leila Tarazi (1994). An Occasion for War: Civil Conflict in Lebanon and Damascus in 1860. London: I.B. Tauris. p. 22. ISBN 1850432015.

- Fawaz, Leila Tarazi (1994). An Occasion for War: Civil Conflict in Lebanon and Damascus in 1860. London: I.B. Tauris. p. 23. ISBN 1850432015.

- Makdisi, Ussama Samir (2000). The Culture of Sectarianism: Community, History, and Violence in Nineteenth-Century Ottoman Lebanon. London: University of California Press. p. 55. ISBN 0-520-21845-0.

- Tomass, Mark (2016). The Religious Roots of the Syrian Conflict: The Remaking of the Fertile Crescent. London: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 151. ISBN 978-1-137-53149-0.

- Tomass, Mark (2016). The Religious Roots of the Syrian Conflict: The Remaking of the Fertile Crescent. London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 151–152. ISBN 978-1-137-53149-0.

- Phillips, Christopher (1 February 2015). "Sectarianism and Conflict in Syria". Third World Quarterly. 36(2): 364 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- Wehrey, Frederic (2017). Beyond Sunni and Shia: The Roots of Sectarianism in a Changing Middle East. London: Hurst & Company. p. 65. ISBN 9781849048149.

- van Dam, Nikolaos (1981). The Struggle for Power in Syria: Sectarianism, Regionalism and Tribalism in Politics, 1961-1980. London: Croom Helm. pp. 111–113. ISBN 0-7099-2601-4.

- Phillips, Christopher (1 February 2015). "Sectarianism and Conflict in Syria". Third World Quarterly. 36(2): 366.

- Tomass, Mark (2016). The Religious Roots of the Syrian Conflict: The Remaking of the Fertile Crescent. London: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 156. ISBN 978-1-137-53149-0.

- Tomass, Mark (2016). The Religious Roots of the Syrian Conflict: The Remaking of the Fertile Crescent. London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 156–157. ISBN 978-1-137-53149-0.

- Phillips, Christopher (1 February 2015). "Sectarianism and Conflict in Syria". Third World Quarterly. 36(2): 357 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- Sahner, Christian C. (2014). Among the Ruins: Syria Past and Present. London: Hurst & Company. p. 81. ISBN 9781849044004.

- Phillips, Christopher (1 February 2015). "Sectarianism and Conflict in Syria". Third World Quarterly. 36(2): 359 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- Wehrey, Frederic (2017). Beyond Sunni and Shia: The Roots of Sectarianism in a Changing Middle East. London: Hurst & Company. pp. 61–62. ISBN 9781849048149.

- Wehrey, Frederic (2017). Beyond Sunni and Shia: The Roots of Sectarianism in a Changing Middle East. London: Hurst & Company. p. 68. ISBN 9781849048149.

- Phillips, Christopher (1 February 2015). "Sectarianism and Conflict in Syria". Third World Quarterly. 36(2): 358 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- Phillips, Christopher (1 February 2015). "Sectarianism and Conflict in Syria". Third World Quarterly. 36(2): 370 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- Salafi-Houthi clashes in Yemen kill 14 Archived 22 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine retrieved 6 February 2012

- "How sectarianism shapes Yemen's war". The Washington Post. 13 April 2015.

- Brehony, Noel; Al-Sarhan, Saud (2015). Rebuilding Yemen: political, economic and social challenges. Berlin: Gerlach Press. pp. 2, 3, 7, 10, 11, 12, 27, 28. ISBN 978-3-940924-69-8.

- Potter, Lawrence (2014). Sectarian Politics in the Persian Gulf. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 207–228. ISBN 978-0-19-937-726-8.

- Day, Stephen (2012). Regionalism and Rebellion in Yemen: A Troubled National Union. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–312, 43, 149, 152, 194, 199, 215, 216, 259, 261, 262, 294. ISBN 978-1-139-42415-8.

- Hull, Edmund (2011). High-value target: countering al Qaeda in Yemen. Virginia: Potomac Books. pp. Introduction. ISBN 978-1-59797-679-4.

- Hashemi, Nader; Postel, Danny (2017). Sectarianization: Mapping the new politics of the Middle East. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 207–228. ISBN 978-0-19-937-726-8.

- Stookey, Robert (1978). Yemen: the politics of the Yemen Arab Republic. Colorado: Westview Press. pp. 21, 22, 163, 164, 172, 173, 182, 234, 253. ISBN 0-89158-300-9.

- Kuehn, Thomas (2011). Empire, Islam, and politics of difference: Ottoman rule in Yemen, 1849-1919. Leiden: Brill. pp. 28, 201–247. ISBN 978-90-04-21131-5.

- Rabi, Uzi (2015). Yemen: revolution, civil war and unification. London: I.B. Tauris. pp. 14, 15, 22, 23, 68, 161, 166–171, 173–192. ISBN 978-1-78076-946-2.

- Brehony, Noel; Al-Sarhan, Saud (2015). Rebuilding Yemen: political, economic and social challenges. Berlin: Gerlach Press. pp. 2, 3, 7, 10, 11, 12, 27, 28. ISBN 978-3-940924-69-8.

- Brehony, Noel; Al-Sarhan, Saud (2015). Rebuilding Yemen: political, economic and social challenges. Berlin: Gerlach Press. pp. 2, 3, 7, 10, 11, 12, 27, 28. ISBN 978-3-940924-69-8.

- Ferris, Jesse (2012). Nasser's Gamble: How Intervention in Yemen Caused the Six-Day War and the Decline of Egyptian Power. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-4523-1.

- Day, Stephen (2012). Regionalism and Rebellion in Yemen: A Troubled National Union. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–312, 43, 149, 152, 194, 199, 215, 216, 259, 261, 262, 294. ISBN 978-1-139-42415-8.

- El Rajji, Rania (2016). "'Even war discriminates': Yemen's minorities, exiled at home" (PDF). Minority Rights Group International.

- Schmidt, Dana (1968). Yemen: the unknown war. London: The Bodley Head. pp. 76, 103, 104.

- Stookey, Robert (1978). Yemen: the politics of the Yemen Arab Republic. Colorado: Westview Press. pp. 21, 22, 163, 164, 172, 173, 182, 234, 253. ISBN 0-89158-300-9.

- Wedeen, Lisa (2008). Peripheral visions: publics, power, and performance in Yemen. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 2, 46–51, 149–150, 153–157, 165–167, 180–185. ISBN 978-0-226-87791-4.

- Lackner, Helen (2017). Yemen in crisis: autocracy, neo-liberalism and the disintegration of a state. London: Saqi Books. pp. 37, 49, 50, 56, 70, 72, 81, 82, 86, 125, 126, 149, 155, 159, 160. ISBN 978-0-86356-193-1.

- Wedeen, Lisa (2008). Peripheral visions: publics, power, and performance in Yemen. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 2, 46–51, 149–150, 153–157, 165–167, 180–185. ISBN 978-0-226-87791-4.

- Day, Stephen (2012). Regionalism and Rebellion in Yemen: A Troubled National Union. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–312, 43, 149, 152, 194, 199, 215, 216, 259, 261, 262, 294. ISBN 978-1-139-42415-8.

- El Rajji, Rania (2016). "'Even war discriminates': Yemen's minorities, exiled at home" (PDF). Minority Rights Group International.

- Lackner, Helen (2017). Yemen in crisis: autocracy, neo-liberalism and the disintegration of a state. London: Saqi Books. pp. 37, 49, 50, 56, 70, 72, 81, 82, 86, 125, 126, 149, 155, 159, 160. ISBN 978-0-86356-193-1.

- Rabi, Uzi (2015). Yemen: revolution, civil war and unification. London: I.B. Tauris. pp. 14, 15, 22, 23, 68, 161, 166–171, 173–192. ISBN 978-1-78076-946-2.

- Fraihat, Ibrahim (2016). Unfinished revolutions: Yemen, Libya, and Tunisia after the Arab Spring. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 39–57, 79–83, 112–116, 161–166, 177–182, 224. ISBN 978-0-300-21563-2.

- Laub, Zachary (2015). "Yemen in Crisis" (PDF). Council on Foreign Relations.

- Brehony, Noel; Al-Sarhan, Saud (2015). Rebuilding Yemen: political, economic and social challenges. Berlin: Gerlach Press. pp. 2, 3, 7, 10, 11, 12, 27, 28. ISBN 978-3-940924-69-8.

- Dorlian, Samy (2011). "The ṣa'da War in Yemen: between Politics and Sectarianism". The Muslim World. 101 (2): 182–201. doi:10.1111/j.1478-1913.2011.01352.x. ISSN 1478-1913.

- Day, Stephen (2012). Regionalism and Rebellion in Yemen: A Troubled National Union. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–312, 43, 149, 152, 194, 199, 215, 216, 259, 261, 262, 294. ISBN 978-1-139-42415-8.

- Al-Hamdani, Raiman; Lackner, Helen (2020). "War and pieces: Political divides in southern Yemen" (PDF). European Council on Foreign Relations.

- Potter, Lawrence (2014). Sectarian Politics in the Persian Gulf. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 207–228. ISBN 978-0-19-937-726-8.

- Wedeen, Lisa (2008). Peripheral visions: publics, power, and performance in Yemen. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 2, 46–51, 149–150, 153–157, 165–167, 180–185. ISBN 978-0-226-87791-4.

- Lackner, Helen (2017). Yemen in crisis: autocracy, neo-liberalism and the disintegration of a state. London: Saqi Books. pp. 37, 49, 50, 56, 70, 72, 81, 82, 86, 125, 126, 149, 155, 159, 160. ISBN 978-0-86356-193-1.

- Rabi, Uzi (2015). Yemen: revolution, civil war and unification. London: I.B. Tauris. pp. 14, 15, 22, 23, 68, 161, 166–171, 173–192. ISBN 978-1-78076-946-2.

- Dorlian, Samy (2011). "The ṣa'da War in Yemen: between Politics and Sectarianism". The Muslim World. 101 (2): 182–201. doi:10.1111/j.1478-1913.2011.01352.x. ISSN 1478-1913.

- Brehony, Noel; Al-Sarhan, Saud (2015). Rebuilding Yemen: political, economic and social challenges. Berlin: Gerlach Press. pp. 2, 3, 7, 10, 11, 12, 27, 28. ISBN 978-3-940924-69-8.

- El Rajji, Rania (2016). "'Even war discriminates': Yemen's minorities, exiled at home" (PDF). Minority Rights Group International.

- Laub, Zachary (2015). "Yemen in Crisis" (PDF). Council on Foreign Relations.

- Gaub, Florence (2015). "Whatever happened to Yemen's army?" (PDF). European Union Institute for Security Studies.

- Day, Stephen (2012). Regionalism and Rebellion in Yemen: A Troubled National Union. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–312, 43, 149, 152, 194, 199, 215, 216, 259, 261, 262, 294. ISBN 978-1-139-42415-8.

- Wedeen, Lisa (2008). Peripheral visions: publics, power, and performance in Yemen. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 2, 46–51, 149–150, 153–157, 165–167, 180–185. ISBN 978-0-226-87791-4.

- Dorlian, Samy (2011). "The ṣa'da War in Yemen: between Politics and Sectarianism". The Muslim World. 101 (2): 182–201. doi:10.1111/j.1478-1913.2011.01352.x. ISSN 1478-1913.

- Rabi, Uzi (2015). Yemen: revolution, civil war and unification. London: I.B. Tauris. pp. 14, 15, 22, 23, 68, 161, 166–171, 173–192. ISBN 978-1-78076-946-2.

- Bonnefoy, Laurent (2018). Yemen and the world: beyond insecurity. London: Hurst & Company. pp. 48–51. ISBN 978-1-849-04966-5.

- Lackner, Helen (2017). Yemen in crisis: autocracy, neo-liberalism and the disintegration of a state. London: Saqi Books. pp. 37, 49, 50, 56, 70, 72, 81, 82, 86, 125, 126, 149, 155, 159, 160. ISBN 978-0-86356-193-1.

- Fraihat, Ibrahim (2016). Unfinished revolutions: Yemen, Libya, and Tunisia after the Arab Spring. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 39–57, 79–83, 112–116, 161–166, 177–182, 224. ISBN 978-0-300-21563-2.

- Gaub, Florence (2015). "Whatever happened to Yemen's army?" (PDF). European Union Institute for Security Studies.

- Brehony, Noel; Al-Sarhan, Saud (2015). Rebuilding Yemen: political, economic and social challenges. Berlin: Gerlach Press. pp. 2, 3, 7, 10, 11, 12, 27, 28. ISBN 978-3-940924-69-8.

- syedjaffar. "The Persecution of Shia Muslims in Saudi Arabia". August 4, 2013. CNN Report. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- "Iraq crisis: How Saudi Arabia helped Isis take over the north of the country," The Independent, 13 July 2014.

- "WikiLeaks Shows a Saudi Obsession With Iran". The New York Times. 16 July 2015.

- "U.S. Backs Saudi-Led Yemeni Bombing With Logistics, Spying". Bloomberg. 26 March 2015.

- "Jihadis likely winners of Saudi Arabia's futile war on Yemen's Houthi rebels". The Guardian. 7 July 2015.

- "'Army of Conquest' rebel alliance pressures Syria regime". Yahoo News. 28 April 2015.

- "Gulf allies and ‘Army of Conquest’". Al-Ahram Weekly. 28 May 2015.

- Kim Sengupta (12 May 2015). "Turkey and Saudi Arabia alarm the West by backing Islamist extremists the Americans had bombed in Syria". The Independent.

- "Saudi execution of Shia cleric sparks outrage in Middle East". The Guardian. 2 January 2016.

- Bahout, Joseph (18 November 2013). "Sectarianism in Lebanon and Syria: The Dynamics of Mutual Spill-Over". United States Institute of Peace.

- Hirst, David (2011). Beware of Small States: Lebanon, Battleground of the Middle East. Nation Books. p. 2.

- Makdisi, Ussama (2000). The Culture of Sectarianism: Community, History, and Violence in Nineteenth-Century Ottoman Lebanon. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. xi.

- Makdisi, Ussama (2000). The Culture of Sectarianism: Community, History, and Violence in Nineteenth-Century Ottoman Lebanon. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 11.

- Makdisi, Ussama (2000). The Culture of Sectarianism: Community, History, and Violence in Nineteenth-Century Ottoman Lebanon. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 2.

- Salamey, Imad (2014). The Government and Politics of Lebanon. London: Routledge. p. 57.

- Rogan, Eugene (2009). The Arabs: A History. New York: Basic Books. p. 242.

- Makdisi, Ussama (1996). "Reconstructing the Nation-State: The Modernity of Sectarianism in Lebanon". Middle East Report. 200: 23. doi:10.2307/3013264.

- "Lebanon: The Persistence of Sectarian Conflict". Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs: 5. 2013.

- Rogan, Eugene (2009). The Arabs: A History. New York: Basic Books. p. 382.

- Rogan, Eugene (2009). The Arabs: A History. New York: Basic Books. p. 411.

- Saseen, Sandra (1990). The Taif Accord and Lebanon's Struggle to Regain its Sovereignty. American University International Law Review. p. 67.

- Rogan, Eugene (2009). The Arabs: A History. New York: Basic Books. p. 460.

- Holmes, Oliver (21 March 2014). "Three dead in north Lebanon in spillover from Syria war". Reuters. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- Ryan, Missy (27 March 2014). "Syria refugee crisis poses major threat to Lebanese stability: U.N." Reuters. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

Further reading

- Sectarianism in Syria (Survey Study), The Day After, 2016.

- Middle East sectarianism explained: the narcissism of small differences Victor Argo 13 Apr 2015 Your Middle East

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Sectarianism |

| Look up sectarian in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Non-Sectarian Religion by Bhaktivinoda Thakura 1880