Makea Takau Ariki

Makea Takau Ariki (1839–1911) was a sovereign of the Cook Islands. She was the ariki (queen) of the dynasty Makea Nui (Great Makea), one of the three chiefdoms of the tribe Te Au O Tonga (The mist of the south) on the island of Rarotonga.

| Makea Takau Ariki | |

|---|---|

| High Chiefess of Rarotonga Queen of the Cook Islands | |

Makea Takau Ariki, Auckland visit (1885) | |

| Reign | 1871–1911 |

| Predecessor | Makea Apera Ariki |

| Successor | Makea Rangi Ariki |

| Born | circa 1839 Avarua, Rarotonga |

| Died | 1 May 1911 (aged 72) |

| Spouse | Ngamaru Rongotini Ariki |

| Issue | none |

| House | House of Te Au O Tonga |

| Dynasty | Makea Nui Dynasty |

| Father | Papelna (?–1901) or Tiberio, Pastor of the LMS |

| Mother | Makea Te Vaerua Ariki |

She succeeded her uncle Makea Abera Ariki in 1871.[1] Her reign lasted forty years during a crucial time in the history of Rarotonga and the Cook Islands. It was under her reign that the Cook Islands became a British protectorate in 1888 before being annexed to New Zealand in 1900.[2]

Family

Makea Takau was adopted by her uncle, Makea Davida, her birth mother was his sister, Makea Te Vaerua Ariki, who was the eldest daughter of Makea Pori Ariki.[3]

Succession

Makea Davida, was ariki of Te Au O Tonga from 1839 until 1849 and succeeded by his sister, Te Vaerua, until her death in 1857. She was succeeded by her younger brother Makea Daniela, until his death in 1866. He was succeeded by another brother, Makea Abera (also spelled Abela), who was in office until his death in 1871.[4]

Marriage

In the 1860s she married Ngamaru Rongotini Ariki, one of the three high chiefs of Atiu and of the adjoining islands of Mauke, and Mitiaro. The marriage was childless. The Prince Consort, Ngamaru, was known to be more warlike than she; he threatened people who offended him by making the "cannibal sign" at them—rapidly drawing his clenched fist across his teeth; the significance being: "I will tear you with my teeth!"[5] He died in 1903.

According to Beatrice Grimshaw, a journalist from Ireland who visited in 1907, it was a happy marriage.

Their married life was a happy one, in spite of the prince's violent character, and when he died, the widowed queen took all her splendid robes of velvet, silk, and satin gorgeously trimmed with gold, tore them in fragments, and cast them into his grave, so that he might lie soft, as befitted the prince who had been loved so well by such a queen.[6]

Reign

France's armed takeover of Tahiti and the Society Islands in 1843 caused considerable apprehension among the Cook Islands' ariki and led to requests from them to the British for protection in the event of French attack. This nervousness continued for many years and the call for protection was repeated in 1865 in a petition to Governor Grey of New Zealand.

During the 1870s the Cook Islands enjoyed prosperity and peace under the authority of Queen Makea, Makea Takau as she was known. A wily negotiator, she secured good prices for exports and cut the debts which had piled up before she became ariki. By 1882 four of the five ariki of Rarotonga were women. In 1888 she formally petitioned the British to set up a Protectorate to head off what she believed to be imminent invasion by the French.

The British were reluctant administrators and continued pressure was applied to them from New Zealand and from European residents of the islands to pass the Cook Islands over to New Zealand. The first British Resident was Frederick Moss, a New Zealand politician who tried to help the local chiefs form a central government. In 1898 another New Zealander, Major W.E. Gudgeon, a veteran of the New Zealand Wars, was made British Resident with the aim of paving the way for New Zealand to take over from Britain as part of the expansionist ambitions of New Zealand's Prime Minister, Richard Seddon. This was not favored by Makea Takau who preferred the idea of being annexed to Britain. One of the results of the British annexation was freedom of religion and a new influx of missionaries from different denominations. The first Roman Catholic church was dedicated in 1896.

After much maneuvering and politicking, the Cook Islands was formally annexed by New Zealand on 7 October 1900 when a deed of cession was signed by five ariki and seven lesser chiefs without any debate or examination of its ramifications or implications.[7]

Titles and styles

- 1871–1911 Makea Takau Ariki, 27th Makea Nui Ariki of the Te-Au-o-Tonga Tribe

- 1874–1911 Queen/Supreme High Chiefess of the Cook Islands

- 1888–1900 Leader of the Council of Chiefs

- 1891–1901 President of the Executive Council

Para O Tane Palace

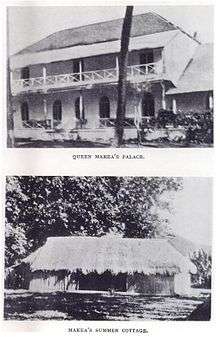

In Avarua are the Para O Tane Palace and its surrounding area, the Taputapuatea marae. Named after a marae in the Society Islands, Taputapuatea was once the largest, most sacred marae in Rarotonga. The palace is where the queen signed the treaty accepting the Cook Islands' status as a British protectorate on 26 October 1888. Beatrice Grimshaw gives a brief description of the palace during her visit to Rarotonga in 1907.

We walked through the blazing hot sun of the tropic afternoon, down the palm-shaded main street of Avarua town, to the great grassy enclosure that surrounds the palace of the queen. One enters through a neat white gate; inside are one or two small houses, a number of palms and flowering bushes, and at the far end, a stately two-storeyed building constructed of whitewashed concrete, with big railed-in verandahs, and handsome arched windows. This is Makea's palace, but her visitors do not go there to look for her. In true South Sea Islander fashion, she keeps a house for show and one for use.[8]

The building was a ruin for many years and was closed to the public, although officially it remained one of the island's main seats of power. In 1990 a group of Auckland University Students joined with local volunteers to rebuild the structure. Over a period of 3 years the building was restored and is now largely as it was in its heyday.[9]

Death

After a prolonged illness, Queen Makea died at midnight on 1 May 1911. During her illness she was looked after by Doctor Perceval, the Chief Medical Officer in Rarotonga. The Resident Commissioner, Captain J. Eman Smith, visited the Palace daily for several weeks and was with her when she died. She was 72 years of age. Her body lay in state until Wednesday 3 May, and viewed by numbers of the residents. She was buried in the family graveyard on the Palace grounds.[10]

Succession

Queen Makea named Rangi Makea as her successor.[11] On 24 October 1911 he was installed as Ariki. The late Queen was head of Government and her successor did not receive a similar appointment, but was of equal status to all the other Arikis.[12]

See also

References

- "Cook Islands Heads of State". guide2womenleaders.com. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- "History of the Cook Islands: The British period". www.ck.

- "Cook Islands Heads of State". guide2womenleaders.com. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- Maretu, Marjorie Crocombe (1983). Cannibals and Converts. p. 96.

- "Beatrice Grimshaw". Black Dog Books.

- Beatrice Grimshaw (1907). In the Strange South Seas. Hutchinson & Company. p. 71.

- "History of the Cook Islands: The British period". www.ck.

- Beatrice Grimshaw (1907). In the Strange South Seas. Hutchinson & Company. p. 68.

- "Image of restored Para O Tane Palace". Flickr images.

- "Death of Queen Makea". Auckland Star. 26 May 1911.

- Photograph of Lord Liverpool & Rangi Makea Ariki, Museum of New Zealand

- "Late Queen's Successor". Grey River Argus. 20 November 1911.

Bibliography

- Rev. William Wyatt Gill, B.A., LL.D.

- Beatrice Ethel Grimshaw, In the Strange South Seas, Ayer Publishing (1909)

- Richard Philip Gilson, The Cook Islands, 1820–1950, Victoria University of Wellington (1980) ISBN 0705507351

- Marjorie Crocombe (editor) & Maretu Cannibals and Converts, University of the South Pacific (1987) ISBN 9820201667

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Makea Takau Ariki. |

- Queen Makea's Country, Auckland Star (1903) (Papers Past)

- Hoisting of the British Flag at Rarotonga and other Islands (NZETC)

- Pedigree of Makea Takau, as given by herself in 1883 (NZETC)

- Rarotongan Genealogy – Genealogy of the Kings of Rarotonga (NZETC)

- Kings of Rarotonga, as given by the "Wise Men" of Makea & Tinomana in 1869 (NZETC)

- Collections Online – Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (Photographs)

- "Cook Islands Makea Nui". Royalty and Nobility from around the world. Retrieved 9 September 2017.