John Williams (missionary)

John Williams (27 June 1796 – 20 November 1839) was an English missionary, active in the South Pacific. Born at Tottenham,[2] near London, England, he was trained as a foundry worker and mechanic.

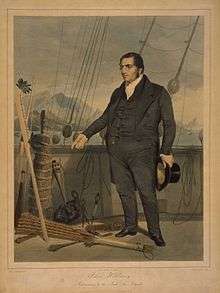

John Williams | |

|---|---|

Painting by George Baxter, 1843 | |

| Born | 27 June 1796 |

| Died | 20 November 1839 (aged 43) |

In September 1816, the London Missionary Society (LMS) commissioned him as a missionary in a service held at Surrey Chapel, London.

South Pacific missionary

In 1817, John Williams and his wife, Mary Chawner Williams, voyaged to the Society Islands, a group of islands that included Tahiti, accompanied by William Ellis and his wife. John and Mary established their first missionary post on the island of Raiatea. From there, they visited a number of the Polynesian island chains, sometimes with Mr and Mrs Ellis and other London Missionary Society representatives. Landing on Aitutaki in 1821, they used Tahitian converts to carry their message to the Cook islanders. One island in this group, Rarotonga (Captain John Dabs of the colonial schooner Endeavour in August 1823 was the first European to sight the islands, with Rev. Williams on board), rises out of the sea as jungle-covered mountains of orange soil ringed by coral reef and turquoise lagoon; Williams became fascinated by it. John and Mary had ten children, but only three survived to adulthood.[3] The Williamses became the first missionary family to visit Samoa.

In 1827 Williams had heard of other heathen islands in the vicinity and in order to expand his ministry he built a ship from local materials, the Messenger of Peace, in fifteen weeks. He set sail by November 1827 for the Society Islands, not returning till February 1828, when he then removed his family to Raiatea.[4]

John Williams arrived in Samoa in 1830, among his crew, a Samoan couple, Fauea and his wife Puaseisei, who joined them on their voyage and proved pivotal in the mission in Samoa. They set foot on the island of Savaii at Puaseisei's village of Safune, before arriving at Sapapalii on the 24th of August, 1830, to meet with Malietoa Vaiinuupo who had sole power over Samoa following the death of his rival Tamafaiga. Williams' meeting with Malietoa proved a success, as Malietoa accepted Christianity immediately.

The Williamses returned in 1834 to Britain, where John supervised the printing of his translation of the New Testament into the Rarotongan language. They brought back a native of Samoa named Leota, who came to live as a Christian in London. At the end of his days, Leota was buried in Abney Park Cemetery with a dignified headstone paid for by the London Missionary Society, recording his adventure from the South Seas island of his birth. Whilst back in London, John Williams published a "Narrative of Missionary Enterprises in the South Sea Islands", making a contribution to English understanding and popularity of the region, before returning to the Polynesian islands in 1837 on the ship Camden under the command of Captain Robert Clark Morgan.

Death

.jpg)

Most of the Williamses' missionary work, and their delivery of a cultural message, was very successful and they became famed in Congregational circles. However, in November 1839, while visiting a part of the New Hebrides where John Williams was unknown, he and fellow missionary James Harris were killed and eaten by cannibals on the island of Erromango during an attempt to bring them the Gospel.

A memorial stone was erected on the island of Rarotonga in 1839 and is still there. Mrs. Williams died in June 1852. She is buried with their son Rev Samuel Tamatoa Williams, who was born in the New Hebrides, at the old Cedar Circle in London's Abney Park Cemetery; the name of her husband and the record of his death were placed on the most prominent side of the stone monument.[5]

Legacy

The LMS successively operated seven missionary ships in the Pacific which were named after John Williams. They were funded by donations from children. The first, John Williams, was launched in 1844,[6] and the last, John Williams VII, was decommissioned in 1968.[7]

In December 2009 descendants of John and Mary Williams travelled to Erromango to accept the apologies of descendants of the cannibals in a ceremony of reconciliation. To mark the occasion, Dillons Bay was renamed Williams Bay.[8][9]

Notes

- London Missionary Society, ed. (1869). Fruits of Toil in the London Missionary Society. London: John Snow & Co. p. 30. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- "Wills & Admons = Pt II, KÜCK, John". q.v. Public Record Office (PRO). Retrieved 6 February 2010.

- Maretu (1983). Cannibals and Converts: Radical Change in the Cook Islands. Institute of Pacific Studies. p. 95. ISBN 9820201667.

Maretu (1802-1880), his work translated, annotated, edited by Marjorie Tuainekore Crocombe

- Walks in Abney Park Cemetery' by James French

- Wingfield, Chris (2015). "Ship's bell, United Kingdom". In Jacobs, Karen; Knowles, Chantal; Wingfield, Chris (eds.). Trophies, Relics and Curios?: Missionary Heritage from Africa and the Pacific. Leiden: Sidestone Press. pp. 127–9. ISBN 978-90-8890-271-0.

- Powerhouse Museum. "H4686 Ship model, SS "John Williams IV", London Missionary Society steamer". Powerhouse Museum, Australia. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- 18.817°S 169.008°W

- "BBC News – Island holds reconciliation over cannibalism". news.bbc.co.uk. 7 December 2009. Retrieved 7 December 2009.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John Williams (missionary). |

- French, James. 1888. Walks in Abney Park Cemetery.

- Hiney, Tom. 2000. On the Missionary Trail: a journey through Polynesia, Asia and Africa with the London Missionary Society.

- Prout, Ebenezer. Memoirs of the Life of the Rev. John Williams, Missionary to Polynesia."

- Williams, John. A Narrative of Missionary Enterprises in the South Sea Islands: With Remarks Upon the Natural History of the Islands, Origin, Traditions, and Usages of the Inhabitants", George Baxter Publisher

.jpg)

.jpg)