Meiji (era)

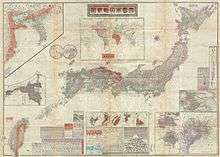

The Meiji era (明治, Meiji, Japanese pronunciation: [meꜜː(d)ʑi]) is an era of Japanese history which extended from October 23, 1868 to July 30, 1912.[1] This era represents the first half of the Empire of Japan, during which period the Japanese people moved from being an isolated feudal society at risk of colonisation by European powers to the new paradigm of a modern, industrialised nation state and emergent great power, influenced by Western scientific, technological, philosophical, political, legal, and aesthetic ideas. As a result of such wholesale adoption of radically-different ideas, the changes to Japan were profound, and affected its social structure, internal politics, economy, military, and foreign relations. The period corresponded to the reign of Emperor Meiji. It was preceded by the Keiō era and was succeeded by the Taishō era, upon the accession of Emperor Taishō.

| History of Japan |

|---|

.jpg) Meiji Constitution promulgation (1889) |

To convert any Gregorian calendar year between 1868 and 1912 to Japanese calendar year in Meiji era, 1867 needs to be subtracted from the year in question.

Meiji Restoration

On February 3, 1867, the 14-year-old Prince Mutsuhito succeeded his father, Emperor Kōmei, to the Chrysanthemum Throne as the 122nd emperor.

On November 9, 1867, then-shōgun Tokugawa Yoshinobu tendered his resignation to the Emperor, and formally stepped down ten days later.[2] Imperial restoration occurred the next year on January 3, 1868, with the formation of the new government. The fall of Edo in the summer of 1868 marked the end of the Tokugawa shogunate, and a new era, Meiji, was proclaimed.

The first reform was the promulgation of the Five Charter Oath in 1868, a general statement of the aims of the Meiji leaders to boost morale and win financial support for the new government. Its five provisions consisted of:

- Deliberative assembly shall be widely established and all matters decided by public discussion

- All classes, high and low, shall unite in vigorously carrying out the administration of the affairs of state

- The common people, no less than the civil and military of officials, shall each be allowed to pursue his own calling so that there may be no discontent.

- Evil customs of the past shall be broken off and everything based upon the just laws of nature.

- Knowledge shall be sought throughout the world so as to strengthen the foundations of imperial rule

Implicit in the Charter Oath was an end to exclusive political rule by the bakufu (a shōgun's direct administration including officers), and a move toward more democratic participation in government. To implement the Charter Oath, a rather short-lived constitution with eleven articles was drawn up in June 1868. Besides providing for a new Council of State, legislative bodies, and systems of ranks for nobles and officials, it limited office tenure to four years, allowed public balloting, provided for a new taxation system, and ordered new local administrative rules.

The Meiji government assured the foreign powers that it would follow the old treaties negotiated by the bakufu and announced that it would act in accordance with international law. Mutsuhito, who was to reign until 1912, selected a new reign title—Meiji, or Enlightened Rule—to mark the beginning of a new era in Japanese history. To further dramatize the new order, the capital was relocated from Kyoto, where it had been situated since 794, to Tokyo (Eastern Capital), the new name for Edo. In a move critical for the consolidation of the new regime, most daimyōs voluntarily surrendered their land and census records to the Emperor in the abolition of the Han system, symbolizing that the land and people were under the Emperor's jurisdiction.

Confirmed in their hereditary positions, the daimyo became governors, and the central government assumed their administrative expenses and paid samurai stipends. The han were replaced with prefectures in 1871, and authority continued to flow to the national government. Officials from the favored former han, such as Satsuma, Chōshū, Tosa, and Hizen staffed the new ministries. Formerly old court nobles, and lower-ranking but more radical samurai, replaced bakufu appointees and daimyo as a new ruling class appeared.

In as much as the Meiji Restoration had sought to return the Emperor to a preeminent position, efforts were made to establish a Shinto-oriented state much like it was 1,000 years earlier. Since Shinto and Buddhism had molded into a syncretic belief in the prior one-thousand years and Buddhism had been closely connected with the shogunate, this involved the separation of Shinto and Buddhism (shinbutsu bunri) and the associated destruction of various Buddhist temples and related violence (haibutsu kishaku). Furthermore, a new State Shinto had to be constructed for the purpose. In 1871, the Office of Shinto Worship (ja:神祇省) was established, ranking even above the Council of State in importance. The kokutai ideas of the Mito school were embraced, and the divine ancestry of the Imperial House was emphasized. The government supported Shinto teachers, a small but important move. Although the Office of Shinto Worship was demoted in 1872, by 1877 the Home Ministry controlled all Shinto shrines and certain Shinto sects were given state recognition. Shinto was released from Buddhist administration and its properties restored. Although Buddhism suffered from state sponsorship of Shinto, it had its own resurgence. Christianity also was legalized, and Confucianism remained an important ethical doctrine. Increasingly, however, Japanese thinkers identified with Western ideology and methods.

Politics

A major proponent of representative government was Itagaki Taisuke (1837–1919), a powerful Tosa leader who had resigned from the Council of State over the Korean affair in 1873. Itagaki sought peaceful, rather than rebellious, means to gain a voice in government. He started a school and a movement aimed at establishing a constitutional monarchy and a legislative assembly. Such movements were called The Freedom and People's Rights Movement. Itagaki and others wrote the Tosa Memorial (ja:民撰議院設立建白書) in 1874, criticizing the unbridled power of the oligarchy and calling for the immediate establishment of representative government.

Between 1871 and 1873, a series of land and tax laws were enacted as the basis for modern fiscal policy. Private ownership was legalized, deeds were issued, and lands were assessed at fair market value with taxes paid in cash rather than in kind as in pre-Meiji days and at slightly lower rates.

Dissatisfied with the pace of reform after having rejoined the Council of State in 1875, Itagaki organized his followers and other democratic proponents into the nationwide Aikokusha (Society of Patriots) to push for representative government in 1878. In 1881, in an action for which he is best known, Itagaki helped found the Jiyūtō (Liberal Party), which favored French political doctrines.

In 1882, Ōkuma Shigenobu established the Rikken Kaishintō (Constitutional Progressive Party), which called for a British-style constitutional democracy. In response, government bureaucrats, local government officials, and other conservatives established the Rikken Teiseitō (Imperial Rule Party), a pro-government party, in 1882. Numerous political demonstrations followed, some of them violent, resulting in further government restrictions. The restrictions hindered the political parties and led to divisions within and among them. The Jiyūtō, which had opposed the Kaishinto, was disbanded in 1884 and Ōkuma resigned as Kaishintō president.

Government leaders, long preoccupied with violent threats to stability and the serious leadership split over the Korean affair, generally agreed that constitutional government should someday be established. The Chōshū leader Kido Takayoshi had favored a constitutional form of government since before 1874, and several proposals for constitutional guarantees had been drafted. While acknowledging the realities of political pressure, however, the oligarchy was determined to keep control. Thus, modest steps were taken.

The Osaka Conference in 1875 resulted in the reorganization of government with an independent judiciary and an appointed Chamber of Elders (Genrōin) tasked with reviewing proposals for a legislature. The Emperor declared that "constitutional government shall be established in gradual stages" as he ordered the Council of Elders to draft a constitution.

Three years later, the Conference of Prefectural Governors established elected prefectural assemblies. Although limited in their authority, these assemblies represented a move in the direction of representative government at the national level, and by 1880 assemblies also had been formed in villages and towns. In 1880 delegates from twenty-four prefectures held a national convention to establish the Kokkai Kisei Dōmei.

Although the government was not opposed to parliamentary rule, confronted with the drive for "people's rights", it continued to try to control the political situation. New laws in 1875 prohibited press criticism of the government or discussion of national laws. The Public Assembly Law (1880) severely limited public gatherings by disallowing attendance by civil servants and requiring police permission for all meetings.

Within the ruling circle, however, and despite the conservative approach of the leadership, Okuma continued as a lone advocate of British-style government, a government with political parties and a cabinet organized by the majority party, answerable to the national assembly. He called for elections to be held by 1882 and for a national assembly to be convened by 1883; in doing so, he precipitated a political crisis that ended with an 1881 imperial rescript declaring the establishment of a national assembly in 1890 and dismissing Okuma.

Rejecting the British model, Iwakura and other conservatives borrowed heavily from the Prussian constitutional system. One of the Meiji oligarchy, Itō Hirobumi (1841–1909), a Chōshū native long involved in government affairs, was charged with drafting Japan's constitution. He led a constitutional study mission abroad in 1882, spending most of his time in Germany. He rejected the United States Constitution as "too liberal", and the British system as too unwieldy, and having a parliament with too much control over the monarchy; the French and Spanish models were rejected as tending toward despotism.

Ito was put in charge of the new Bureau for Investigation of Constitutional Systems in 1884, and the Council of State was replaced in 1885 with a cabinet headed by Ito as prime minister. The positions of chancellor (or chief-minister), minister of the left, and minister of the right, which had existed since the seventh century as advisory positions to the Emperor, were all abolished. In their place, the Privy Council was established in 1888 to evaluate the forthcoming constitution and to advise the Emperor.

To further strengthen the authority of the State, the Supreme War Council was established under the leadership of Yamagata Aritomo (1838–1922), a Chōshū native who has been credited with the founding of the modern Japanese army and was to become the first constitutional Prime Minister. The Supreme War Council developed a German-style general staff system with a chief of staff who had direct access to the Emperor and who could operate independently of the army minister and civilian officials.

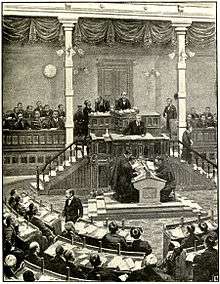

The Constitution of the Empire of Japan was enacted on November 29, 1890.[3] It was a form of mixed constitutional and absolute monarchy.[4] The Emperor of Japan was legally the supreme leader, and the Cabinet were his followers. The Prime Minister would be elected by a Privy Council. In reality, the Emperor was head of state but the Prime Minister was the actual head of government.

Class distinctions were mostly eliminated during modernization to create a representative democracy. The samurai lost their status as the only class with military privileges. However, during the Meiji period, most leaders in Japanese society (politics, business and military) were ex-samurai or descendants of samurai.

The 1889 Meiji Constitution made relatively small concessions to civil rights and parliamentary mechanisms. Party participation was recognized as part of the political process. The Emperor shared his authority and give rights and liberties to his subjects. It provided for the Imperial Diet (Teikoku Gikai), composed of a popularly elected House of Representatives with a very limited franchise of male citizens who were over twenty-five years of age and paid fifteen yen in national taxes (approximately 1% of the population). The House of Peers was composed of nobility and imperial appointees. A cabinet was responsible to the Emperor and independent of the legislature. The Diet could approve government legislation and initiate laws, make representations to the government, and submit petitions to the Emperor. The Meiji Constitution lasted as the fundamental law until 1947.

In the early years of constitutional government, the strengths and weaknesses of the Meiji Constitution were revealed. A small clique of Satsuma and Chōshū elite continued to rule Japan, becoming institutionalized as an extra-constitutional body of genrō (elder statesmen). Collectively, the genro made decisions reserved for the Emperor, and the genro, not the Emperor, controlled the government politically.

Throughout the period, however, political problems usually were solved through compromise, and political parties gradually increased their power over the government and held an ever-larger role in the political process as a result. Between 1891 and 1895, Ito served as Prime Minister with a cabinet composed mostly of genro who wanted to establish a government party to control the House of Representatives. Although not fully realized, the trend toward party politics was well established.

Society

On its return, one of the first acts of the government was to establish new ranks for the nobility. Five hundred people from the old court nobility, former daimyo, and samurai who had provided valuable service to the Emperor were organized into a new peerage, the Kazoku, consisting of five ranks: prince, marquis, count, viscount, and baron.

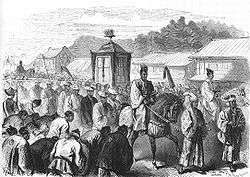

In the transition between the Edo period and the Meiji era, the Ee ja nai ka movement, a spontaneous outbreak of ecstatic behavior, took place.

In 1885, noted public intellectual Yukichi Fukuzawa wrote the influential essay "Leaving Asia", arguing that Japan should orient itself at the "civilized countries of the West", leaving behind the "hopelessly backward" Asian neighbors, namely Korea and China. This essay certainly encouraged the economic and technological rise of Japan in the Meiji era, but it also may have laid the intellectual foundations for later Japanese colonialism in the region.

The Meiji era saw a flowering of public discourse on the direction of Japan. Works like Nakae Chōmin's A Discourse by Three Drunkards on Government[5] debated how best to blend the new influences coming from the West with local Japanese culture. Grassroots movements like the Freedom and People's Rights Movement called for the establishment of a formal legislature, civil rights, and greater pluralism in the Japanese political system. Journalists, politicians, and writers actively participated in the movement, which attracted an array of interest groups, including women's rights activists.[6]

The elite class of the Meiji era adapted many aspects of Victorian taste, as seen in the construction of Western-style pavilions and reception rooms called yōkan or yōma in their homes. These parts of Meiji homes were displayed in popular magazines of the time, such as Ladies' Graphic, which portrayed the often empty rooms of the homes of the aristocracy of all levels, including the imperial palaces. Integrating Western cultural forms with an assumed, untouched native Japanese spirit was characteristic of Meiji society, especially at the top levels, and represented Japan's search for a place within a new world power system in which European colonial empires dominated.[7]

Fashion

The production of kimono started to use Western technologies such as synthetic dye, and decoration was sometimes influenced by Western motifs.[8] The textile industry modernised rapidly and silk from Tokyo's factories became Japan's principal export.[9] Cheap synthetic dyes meant that bold purples and reds, previously restricted to the wealthy elite, could be owned by anyone.[10] Faster and cheaper manufacture allowed more people to afford silk kimono, and enabled designers to create new patterns.[10] The Emperor issued a proclamation promoting Western dress over the allegedly effeminate Japanese dress.[11] Fukuzawa Yukichi's descriptions of Western clothing and customs were influential.[12] So Western dress became popular in the public sphere: many men adopted Western dress in the workplace, although kimono were still the norm for men at home and for women.[13] In the 1890s the kimono reasserted itself, with people wearing bolder and brighter styles. A new type called the hōmongi bridged the gap between formal dress and everyday dress.[9]

The technology of the time allowed for subtle colour gradients rather than abrupt changes of colour. Another trend was for outer and inner garments of the same design.[14] Another trend in the Meiji era was for women's under-kimono made by combining pieces of different fabric, sometimes of radically different colours and designs.[15] For men, the trend was for highly decorative under-kimono that would be covered by outer kimono that were plain or very simply designed. Even the clothing of infants and young children used bold colours, intricate designs, and materials common to adult fashions.[16] Japanese exports led to kimono becoming an object of fascination in the West.[17]

Economy

The Industrial Revolution in Japan occurred during the Meiji era. The industrial revolution began about 1870 as Meiji era leaders decided to catch up with the West. The government built railroads, improved roads, and inaugurated a land reform program to prepare the country for further development. It inaugurated a new Western-based education system for all young people, sent thousands of students to the United States and Europe, and hired more than 3,000 Westerners to teach modern science, mathematics, technology, and foreign languages in Japan (O-yatoi gaikokujin).

In 1871, a group of Japanese politicians known as the Iwakura Mission toured Europe and the US to learn western ways. The result was a deliberate state led industrialisation policy to enable Japan to quickly catch up. The Bank of Japan, founded in 1877, used taxes to fund model steel and textile factories.

Modern industry first appeared in textiles, including cotton and especially silk, which was based in home workshops in rural areas.[18] Due to the importing of new textile manufacturing technology from Europe, between 1886 and 1897, Japan's total value of yarn output rose from 12 million to 176 million yen. In 1886, 62% of yarn in Japan was imported; by 1902, most yarn was produced locally. By 1913, Japan was producing 672 million pounds of yarn per year, becoming the fourth largest exporter of cotton yarn.[19]

The first railway was opened between Tokyo and Yokohama in 1872; and railway was rapidly developed throughout Japan well into the twentieth century. The introduction of railway transportation led to more efficient production due to the decline in transport costs; allowing for manufacturing firms to move into more populated interior regions of Japan in search for labour input. The railway also enabled a new-found access to raw materials that had previously been too difficult or costly to transport.[20]

There were at least two reasons for the speed of Japan's modernization: the employment of more than 3,000 foreign experts (called o-yatoi gaikokujin or 'hired foreigners') in a variety of specialist fields such as teaching English, science, engineering, the army and navy, among others; and the dispatch of many Japanese students overseas to Europe and America, based on the fifth and last article of the Charter Oath of 1868: 'Knowledge shall be sought throughout the world so as to strengthen the foundations of Imperial rule.' This process of modernization was closely monitored and heavily subsidized by the Meiji government, enhancing the power of the great zaibatsu firms such as Mitsui and Mitsubishi.

Hand in hand, the zaibatsu and government guided the nation, borrowing technology from the West. Japan gradually took control of much of Asia's market for manufactured goods, beginning with textiles. The economic structure became very mercantilistic, importing raw materials and exporting finished products—a reflection of Japan's relative poverty in raw materials.

Japan emerged from the Tokugawa–Tennō (Keiō–Meiji) transition in 1868 as the first Asian industrialized nation. Domestic commercial activities and limited foreign trade had met the demands for material culture until the Keiō era, but the modernized Meiji era had radically different requirements. From the onset, the Meiji rulers embraced the concept of a market economy and adopted British and North American forms of free enterprise capitalism. The private sector—in a nation with an abundance of aggressive entrepreneurs—welcomed such change.

Economic reforms included a unified modern currency based on the yen, banking, commercial and tax laws, stock exchanges, and a communications network. Establishment of a modern institutional framework conducive to an advanced capitalist economy took time, but was completed by the 1890s. By this time, the government had largely relinquished direct control of the modernization process, primarily for budgetary reasons.

Many of the former daimyo, whose pensions had been paid in a lump sum, benefited greatly through investments they made in emerging industries. Those who had been informally involved in foreign trade before the Meiji Restoration also flourished. Old bakufu-serving firms that clung to their traditional ways failed in the new business environment.

The government initially was involved in economic modernization, providing a number of "model factories" to facilitate the transition to the modern era. After the first twenty years of the Meiji era, the industrial economy expanded rapidly until about 1920 with inputs of advanced Western technology and large private investments. Stimulated by wars and through cautious economic planning, Japan emerged from World War I as a major industrial nation.

In 1885, the Meiji government sponsored a telegraph system, throughout Japan, situating the telegraphs in all major Japanese cities at the time.

Military

Overview

Undeterred by opposition, the Meiji leaders continued to modernize the nation through government-sponsored telegraph cable links to all major Japanese cities and the Asian mainland and construction of railroads, shipyards, munitions factories, mines, textile manufacturing facilities, factories, and experimental agriculture stations. Greatly concerned about national security, the leaders made significant efforts at military modernization, which included establishing a small standing army, a large reserve system, and compulsory militia service for all men. Foreign military systems were studied, foreign advisers, especially French ones, were brought in, and Japanese cadets sent abroad to Europe and the United States to attend military and naval schools.

Early Meiji period (1868–77)

In 1854, after Admiral Matthew C. Perry forced the signing of the Treaty of Kanagawa, Japanese elites took the position that they needed to modernize the state's military capacities, or risk further coercion from Western powers.[21] The Tokugawa shogunate did not officially share this point of view, however, as evidenced by the imprisonment of the Governor of Nagasaki, Shanan Takushima for voicing his views of military reform and weapons modernization.[22]

In 1868, the Japanese government established the Tokyo Arsenal. This arsenal was responsible for the development and manufacture of small arms and associated ammunition.[22] The same year, Ōmura Masujirō established Japan's first military academy in Kyoto. Ōmura further proposed military billets be filled by all classes of people including farmers and merchants. The shōgun class, not happy with Ōmura's views on conscription, assassinated him the following year.[23]

In 1870, Japan expanded its military production base by opening another arsenal in Osaka. The Osaka Arsenal was responsible for the production of machine guns and ammunition.[24] Also, four gunpowder facilities also were opened at this site. Japan's production capacity gradually expanded.

In 1872, Yamagata Aritomo and Saigō Jūdō, both new field marshals, founded the Corps of the Imperial Guards. This corps was composed of the warrior classes from the Tosa, Satsuma, and Chōshū clans.[22] Also, in the same year, the hyobusho (war office) was replaced with a War Department and a Naval Department. The samurai class suffered great disappointment the following years, when in January the Conscription Law of 1873 was passed. This law required every able-bodied male Japanese citizen, regardless of class, to serve a mandatory term of three years with the first reserves and two additional years with the second reserves.[22] This monumental law, signifying the beginning of the end for the samurai class, initially met resistance from both the peasant and warrior alike. The peasant class interpreted the term for military service, ketsu-eki (blood tax) literally, and attempted to avoid service by any means necessary. Avoidance methods included maiming, self-mutilation, and local uprisings.[25] The samurai were generally resentful of the new, western-style military and at first, refused to stand in formation with the peasant class.[22]

In conjunction with the new conscription law, the Japanese government began modeling their ground forces after the French military. Indeed, the new Japanese army used the same rank structure as the French.[26] The enlisted corps ranks were: private, noncommissioned officers, and officers. The private classes were: jōtō-hei or upper soldier, ittō-sotsu or first-class soldier, and nitō-sotsu or second-class soldier. The noncommissioned officer class ranks were: gochō or corporal, gunsō or sergeant, sōchō or sergeant major, and tokumu-sōchō or special sergeant major. Finally, the officer class is made up of: shōi or second lieutenant, chūi or first lieutenant, tai or captain, shōsa or major, chūsa or lieutenant colonel, taisa or colonel, shōshō or major general, chūjō or lieutenant general, taishō or general, and gensui or field marshal.[22] The French government also contributed greatly to the training of Japanese officers. Many were employed at the military academy in Kyoto, and many more still were feverishly translating French field manuals for use in the Japanese ranks.[22]

Despite the Conscription Law of 1873, and all the reforms and progress, the new Japanese army was still untested. That all changed in 1877, when Saigō Takamori led the last rebellion of the samurai in Kyūshū. In February 1877, Saigō left Kagoshima with a small contingent of soldiers on a journey to Tokyo. Kumamoto castle was the site of the first major engagement when garrisoned forces fired on Saigō's army as they attempted to force their way into the castle. Rather than leave an enemy behind him, Saigō laid siege to the castle. Two days later, Saigō's rebels, while attempting to block a mountain pass, encountered advanced elements of the national army en route to reinforce Kumamoto castle. After a short battle, both sides withdrew to reconstitute their forces. A few weeks later the national army engaged Saigō's rebels in a frontal assault at what now is called the Battle of Tabaruzuka. During this eight-day-battle, Saigō's nearly ten thousand strong army battled hand-to-hand the equally matched national army. Both sides suffered nearly four thousand casualties during this engagement. Due to conscription, however, the Japanese army was able to reconstitute its forces, while Saigō's was not. Later, forces loyal to the emperor broke through rebel lines and managed to end the siege on Kumamoto Castle after fifty-four days. Saigō's troops fled north and were pursued by the national army. The national army caught up with Saigō at Mt. Enodake. Saigō's army was outnumbered seven-to-one, prompting a mass surrender of many samurai. The remaining five hundred samurai loyal to Saigō escaped, travelling south to Kagoshima. The rebellion ended on September 24, 1877, following the final engagement with Imperial forces which resulted in the deaths of the remaining forty samurai including Saigō, who, having suffered a fatal bullet wound in the abdomen, was honourably beheaded by his retainer. The national army's victory validated the current course of the modernization of the Japanese army as well as ended the era of the samurai.

Foreign relations

When the United States Navy ended Japan's sakoku policy, and thus its isolation, the latter found itself defenseless against military pressures and economic exploitation by the Western powers. For Japan to emerge from the feudal period, it had to avoid the colonial fate of other Asian countries by establishing genuine national independence and equality. Following the María Luz Incident, Japan released the Chinese coolies from a western ship in 1872, after which the Qing imperial government of China gave thanks to Japan.

Following Japan's victory over China in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), Japan broke through as an international power with a victory against Russia in Manchuria (north-eastern China) in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905. Allied with Britain since the Anglo-Japanese Alliance signed in London on January 30, 1902, Japan joined the Allies in World War I, seizing German-held territory in China and the Pacific in the process, but otherwise remained largely out of the conflict.

Following World War I, a weakened Europe left a greater share in international markets to the United States and Japan, which emerged greatly strengthened. Japanese competition made great inroads into hitherto-European-dominated markets in Asia, not only in China, but even in European colonies such as India and Indonesia, reflecting the development of the Meiji era.

The final years of the Meiji era were also marked by the annexation of Korea in 1911; Japan's occupation of the peninsula nation would persist until Japan's loss in World War II in 1945, during the middle of the Shōwa period, and would have lasting negative repercussions on foreign relations between Japan and North and South Korea.

Art

The government took an active interest in the art export market, promoting Japanese arts at a succession of world's fairs, beginning with the 1873 Vienna World's Fair.[27][28] As well as heavily funding the fairs, the government took an active role organising how Japan's culture was presented to the world. It created a semi-public company — the Kiritsu Kosho Kaisha (First Industrial Manufacturing Company) — to promote and commercialize exports of art[29] and established the Hakurankai Jimukyoku (Exhibition Bureau) to maintain quality standards.[28] For the 1876 Centennial International Exhibition in Philadelphia, the Japanese government created a Centennial Office and sent a special envoy to secure space for the 30,000 items that would be displayed.[30] The Imperial Household also took an active interest in arts and crafts, commissioning works ("presentation wares") as gifts for foreign dignitaries.[31] In 1890, the Teishitsu Gigeiin (Artist to the Imperial Household) system was created to recognise distinguished artists; seventy were appointed from 1890 to 1944.[32] Among these were the painter and lacquer artist Shibata Zeshin, ceramicist Makuzu Kōzan, painter Hashimoto Gahō, and cloisonné enamel artist Namikawa Yasuyuki.[32]

As Western imports became popular, demand for Japanese art declined within Japan itself.[33] In Europe and America, the new availability of Japanese art led to a fascination for Japanese culture; a craze known in Europe as Japonisme.[34] Imperial patronage, government sponsorship, promotion to new audiences, and Western technology combined to foster an era of Japanese artistic innovation. In the decorative arts, Japanese artists reached new levels of technical sophistication.[29]

Enamels

.jpg)

During the Meiji era, Japanese cloisonné enamel reached a technical peak, producing items more advanced than any that had existed before.[35] The period from 1890 to 1910 was known as the "Golden age" of Japanese enamels.[36] Artists experimented with pastes and with the firing process to produce ever larger blocks of enamel, with less need for cloisons (enclosing metal strips).[35] During this period, enamels with a design unique to Japan, in which flowers, birds and insects were used as themes and the space was utilized, became popular.[37] The two most famous enamelers of this era were Namikawa Yasuyuki and Namikawa Sōsuke, whose family names sound the same but who were not related.[37] Namikawa Sōsuke promoted his work as technically innovative, and adopted a style resembling fine paintings. Namikawa Yasuyuki was more conservative, opting for geometrical patterns but gradually becoming more pictorial during his career.[38] Along with the two Namikawa, the Ando Cloisonné Company has produced many high-quality cloisonné works.

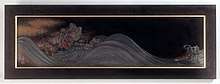

Lacquerware

Gold- or silver-decorated lacquerwares had been popular in the Edo period, but fell out of favour in the early nineteenth-century due to economic hardship.[39] The Meiji era saw a renewed interest in lacquer as artists developed new designs and experimented with new textures and finishes. Foremost among these was Shibata Zeshin,[39] who has been called "Japan's greatest lacquerer".[40] The appeal of his highly original style was in the choice of motifs and subject matter rather than embedded gold and silver. He placed lacquer panels in frames, imitating Western oil paintings.[41] Other notable lacquer artists of the 19th century include Nakayama Komin and Shirayama Shosai, both of whom, in contrast with Zeshin, maintained a classical style that owed a lot to Chinese landscape art.[42] Maki-e, decorating the lacquer in gold or silver dust, was the most common technique for quality lacquerware in this period.[43] Lacquer from Japanese workshops was recognised as technically superior to what could be produced anywhere else in the world.[41]

Metalwork

At the start of the Meiji era, Japanese metalwork was almost totally unknown outside the country, unlike lacquer and porcelain which had previously been exported.[44] Metalwork was connected to Buddhist practice, for example in the use of bronze for temple bells and incense cauldrons, so there were fewer opportunities for metalworkers once Buddhism was displaced as the state religion.[44] International exhibitions brought Japanese cast bronze to a new foreign audience, attracting strong praise.[44] Suzuki Chokichi, a leading producer of cast bronze for international exhibition, became director of the Kiritsu Kosho Kaisha from 1874 to the company's dissolution in 1891. In 1896 he was appointed Artist to the Imperial Household.[44] The works of Chokichi and his contemporaries took inspiration from late Edo period carvings and prints, combining and sometimes exaggerating traditional design elements in new ways to appeal to the export market.[45] The past history of samurai weaponry equipped Japanese metalworkers to create metallic finishes in a wide range of colours. By combining and finishing copper, silver and gold in different proportions, they created specialised alloys including shakudō and shibuichi. With this variety of alloys and finishes, an artist could give the impression of full-colour decoration.[46] Some of these metalworkers were appointed Artists to the Imperial Household, including Kano Natsuo, Unno Shomin, Namekawa Sadakatsu, and Jomi Eisuke II.[47]

Porcelain

Japan's porcelain industry was well-established at the start of the Meiji era, but the mass-produced wares were not known for their elegance.[48] During this era, technical and artistic innovations turned porcelain into one of the most internationally successful Japanese decorative art forms.[48] The career of porcelain artist Makuzu Kōzan is an archetype for the trajectory of Meiji art.[48] He was passionate about preserving traditional influences, but adopted new technologies from the West.[48] He was an entrepreneur as well as an artist, organising a workshop with many artisans[49] and actively promoting his work at international exhibitions, travelling extensively in Europe.[50] As his career went on, he adopted more Western influences on his decoration,[51] while his works shaped Western perceptions of Japanese design.[38] Underglaze blue painting on porcelain was well-established in Japan, and the Kozan workshop transformed this practice, combining multiple underglaze colours on a single item and introducing more subtle graduations of colour.[52]

Satsuma ware was a name originally given to pottery from Satsuma province, elaborately decorated with gilt and enamel. These wares were highly praised in the West. Seen in the West as distinctively Japanese, this style actually owed a lot to imported pigments and Western influences, and had been created with export in mind.[53] Workshops in many cities raced to produce this style to satisfy demand from Europe and America, often producing quickly and cheaply. So the term "Satsuma ware" came to be associated not with a place of origin but with lower-quality ware created purely for export.[54] Despite this, artists such as Yabu Meizan and Makuzu Kōzan maintained the highest artistic standards while also successfully exporting.[55] From 1876 to 1913, Kōzan won prizes at 51 exhibitions, including the World's fair and the National Industrial Exhibition.[56]

Textiles

The 1902 edition of Encyclopædia Britannica wrote, "In no branch of applied art does the decorative genius of Japan show more attractive results than that of textile fabrics, and in none has there been more conspicuous progress during recent years. [...] Kawashima of Kyoto [...] inaugurated the departure a few years ago by copying a Gobelin, but it may safely be asserted that no Gobelin will bear comparison with the pieces now produced in Japan".[57] Very large, colourful pictorial works were being produced in Kyoto. Embroidery had become an art form in its own right, adopting a range of pictorial techniques such as chiaroscuro and aerial perspective.[57]

See also

- Japanese nationalism

- List of political figures of Meiji Japan

- Amakusa coalfield

Notes

- Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005). "Meiji" in Japan encyclopedia, p. 624, p. 624, at Google Books; n.b., Louis-Frédéric is pseudonym of Louis-Frédéric Nussbaum, see Deutsche Nationalbibliothek Authority File.

- Takano, p. 256.

- "Meiji Constitution | 1889, Japan". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

- Hein, Patrick (2009). How the Japanese became foreign to themselves : the impact of globalization on the private and public spheres in Japan. Berlin: Lit. p. 72. ISBN 978-3643100856.

- Nakae, C. and Tsukui, N. and Hammond, J. A Discourse by Three Drunkards on Government. 1984.

- Hane, M. Reflections on the Way to the Gallows: Rebel Women in Prewar Japan. University of California Press. 1988.

- Sand, Jordan (2000). "Was Meiji Taste in Interiors "Orientalist?"". Positions: East Asia Cultures Critique. Duke University Press. 8 (3): 637–673. doi:10.1215/10679847-8-3-637.

- Iwao 2015, p. 11.

- Jackson 2015, p. 117.

- Jackson 2015, p. 118.

- Jackson 2015, p. 112.

- Jackson 2015, p. 113.

- Guth 2015, p. 110.

- Jackson 2015, pp. 126–134.

- Jackson 2015, p. 137.

- Jackson 2015, pp. 142–144.

- Iwao 2015, p. 9.

- Allen, George Cyril (1972). A short economic history of modern Japan, 1867-1937, (3rd rev. ed.). London: Allen and Unwin. ISBN 0-04-330201-7. OCLC 533080.

- Landes, David S. (1999). The Wealth and Poverty of Nations: Why Some Are So Rich and Some So Poor. New York: Norton. pp. 379–80.

- Tang, John P. (September 2014). "Railroad Expansion and Industrialization: Evidence from Meiji Japan". The Journal of Economic History. 74 (3): 863–886. doi:10.1017/S002205071400062X – via CRKN Cambridge University Press Journals.

- Gordon (2000).

- GlobalSecurity.org (2008).

- Shinsengumihq.com, n.d.

- National Diet Library (2008).

- Kublin 1949, p. 32.

- Kublin 1949, p. 31.

- Earle 1999, pp. 30–31.

- Liddell, C. B. (December 14, 2013). "[Review:] Japonisme and the Rise of the Modern Art Movement: The Arts of the Meiji Period". The Japan Times. Retrieved March 19, 2020.

- Earle 1999, p. 31.

- Earle 1999, pp. 32–33.

- Earle 1999, p. 349.

- Earle 1999, pp. 347–348.

- Cortazzi, Sir Hugh (January 16, 2014). "[Review:] Japonisme and the Rise of the Modern Art Movement: The Arts of the Meiji Period, The Khalili Collection". Japan Society of the UK. Archived from the original on August 14, 2014. Retrieved March 19, 2020.

- Earle 1999, p. 29.

- Earle 1999, p. 252.

- Irvine, Gregory (2013). "Wakon Yosai- Japanese spirit, Western techniques: Meiji period arts for the West". In Irvine, Gregory (ed.). Japonisme and the rise of the modern art movement : the arts of the Meiji period : the Khalili collection. New York: Thames & Hudson. p. 177. ISBN 978-0-500-23913-1. OCLC 853452453.

- Earle 1999, p. 254.

- Earle 1999, p. 255.

- Earle 1999, pp. 186–187.

- Earle, Joe, "Zeshin Redux", Orientations, Vol. 29, No. 2, March, 2008, p. 136

- Earle 1999, p. 187.

- Earle 1999, pp. 187–188.

- Earle 1999, p. 185.

- Earle 1999, p. 64.

- Earle 1999, p. 65.

- Earle 1999, p. 66.

- Earle 1999, pp. 66, 70, 237, 370, 372.

- Earle 1999, p. 330.

- Moyra Clare Pollard (2002). Master Potter of Meiji Japan: Makuzu Kōzan (1842-1916) and His Workshop. Oxford University Press. pp. 18–9, 28. ISBN 978-0-19-925255-8.

- Earle 1999, pp. 331–332.

- Earle 1999, p. 335.

- Earle 1999, pp. 111, 335.

- Earle 1999, pp. 116–117.

- Checkland, Olive (2003). Japan and Britain after 1859 : creating cultural bridges. Routledge Curzon. p. 45. ISBN 9781135786199. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- Earle 1999, pp. 117–119.

- 受賞経歴 Makuzu ware Museum

- "Japan" in Encyclopædia Britannica (1902), Volume 29, pages 724–725.

References

- Benesch, Oleg (2018). "Castles and the Militarisation of Urban Society in Imperial Japan" (PDF). Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 28: 107–134. doi:10.1017/S0080440118000063. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 20, 2018. Retrieved November 25, 2018.

- Earle, Joe (1999). Splendors of Meiji : treasures of imperial Japan : masterpieces from the Khalili Collection. St. Petersburg, Fla.: Broughton International Inc. ISBN 1874780137. OCLC 42476594.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- GlobalSecurity.org (2008). Meiji military. Retrieved August 5, 2008.

- Guth, Christine M. E. (2015). "The Meiji era: the ambiguities of modernization". In Jackson, Anna (ed.). Kimono: the art and evolution of Japanese fashion. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 106–111. ISBN 9780500518021. OCLC 990574229.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Iwao, Nagasaki (2015). "Clad in the aesthetics of tradition: from kosode to kimono". In Jackson, Anna (ed.). Kimono: the art and evolution of Japanese fashion. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 8–11. ISBN 9780500518021. OCLC 990574229.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kublin, Hyman (November 1949). "The "modern" army of early meiji Japan". The Far East Quarterly. 9 (1): 20–41. doi:10.2307/2049123.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jackson, Anna (2015). "Dress in the Meiji period: change and continuity". In Jackson, Anna (ed.). Kimono: the art and evolution of Japanese fashion. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 112–151. ISBN 9780500518021. OCLC 990574229.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- National Diet Library (n.d.). Osaka army arsenal (osaka hohei kosho). Retrieved August 5, 2008.

- Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric and Käthe Roth. (2005). Japan encyclopedia. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01753-5; OCLC 58053128

- Rickman, J. (2003). Sunset of the samurai. Military History. August, 42–49.

- Shinsengumihq.com, (n.d.). No sleep, no rest: Meiji law enforcement. Retrieved August 5, 2008.

- Vos, F., et al., Meiji, Japanese Art in Transition, Ceramics, Cloisonné, Lacquer, Prints, Organized by the Society for Japanese Art and Crafts, 's-Gravenhage, the Netherlands, Gemeentemuseum, 1987. ISBN 90-70216-03-5

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Meiji era. |

- (In Japanese) Meiji Taisho 1868–1926

- National Diet Library, "The Japanese Calendar" – historical overview plus illustrative images from library's collection

- "Encouragement for Learning" by Fukuzawa Yukichi, a best-selling book of Meiji Japan (English Translation)

- Milasi, Luca. "“Tra realtà e finzione: la rivalutazione della narrativa premoderna nella critica letteraria Meiji" (" (). XXXIV CONVEGNO DI STUDI SUL GIAPPONE AISTUGIA (16-17-18 settembre 2010) Università degli studi di Napoli "L'Orientale"(Rettorato dell'Università "L'Orientale", Palazzo Du Mesnil, in via Partenope 10/A. (in Italian)

- Narrative of the Expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan, by M.C. Perry, at archive.org

- Kitahara, Michio. Commodore Perry and the Japanese: A Study in the Dramaturgy of Power, 1986

- Black Ships & Samurai Commodore Perry and the Opening of Japan (1853-1854), by John W Dower

Archives

- Lt. John T. Alderson collection of Japan photographs. circa 1890s. 40 photographic prints (1 box) : hand colored ; sizes vary. At the University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections.

| Preceded by Keiō (慶応) |

Era of Japan Meiji (明治) 23 October 1868 – 30 July 1912 |

Succeeded by Taishō (大正) |