Daimyo

Daimyo (大名, Daimyō, Japanese pronunciation: [daimʲoː] (![]()

From the shugo of the Muromachi period through the Sengoku to the daimyo of the Edo period, the rank had a long and varied history. The backgrounds of daimyo also varied considerably; while some daimyo clans, notably the Mōri, Shimazu and Hosokawa, were cadet branches of the Imperial family or were descended from the kuge, other daimyo were promoted from the ranks of the samurai, notably during the Edo period.

Daimyo often hired samurai to guard their land, and they paid the samurai in land or food as relatively few could afford to pay samurai in money. The daimyo era ended soon after the Meiji Restoration with the adoption of the prefecture system in 1871.

The term "daimyo" sometimes refers to the leading figures of such clans, also called "lord". It was usually, though not exclusively, from these warlords that a shogun arose or a regent was chosen.

Shugo-daimyo

The shugo daimyo (守護大名) were the first group of men to hold the title daimyo. They arose from among the shugo during the Muromachi period. The shugo-daimyo held not only military and police powers, but also economic power within a province. They accumulated these powers throughout the first decades of the Muromachi period.

Major shugo-daimyo came from the Shiba, Hatakeyama, and Hosokawa clans, as well as the tozama clans of Yamana, Ōuchi, and Akamatsu. The greatest ruled multiple provinces.

The Ashikaga shogunate required the shugo-daimyo to reside in Kyoto, so they appointed relatives or retainers, called shugodai, to represent them in their home provinces. Eventually some of these in turn came to reside in Kyoto, appointing deputies in the provinces.

The Ōnin War was a major uprising in which shugo-daimyo fought each other. During this and other wars of the time, kuni ikki, or provincial uprisings, took place as locally powerful warriors sought independence from the shugo-daimyo. The deputies of the shugo-daimyo, living in the provinces, seized the opportunity to strengthen their position. At the end of the fifteenth century, those shugo-daimyo who succeeded remained in power. Those who had failed to exert control over their deputies fell from power and were replaced by a new class, the sengoku-daimyo, who arose from the ranks of the shugodai and jizamurai.

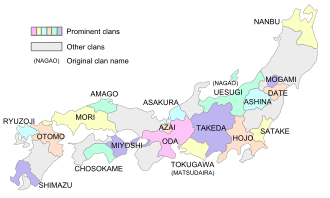

Sengoku-daimyo

Among the sengoku daimyo (戦国大名) were many who had been shugo-daimyo, such as the Satake, Imagawa, Takeda, Toki, Rokkaku, Ōuchi, and Shimazu. New to the ranks of the daimyo were the Asakura, Amago, Nagao, Miyoshi, Chōsokabe, Jimbō, Hatano, Oda, and Matsunaga. These came from the ranks of the shugodai and their deputies. Additional sengoku-daimyo such as the Mōri, Tamura, and Ryūzōji arose from the jizamurai. The lower officials of the shogunate and rōnin (Late Hōjō, Saitō), provincial officials (Kitabatake), and kuge (Tosa Ichijō) also gave rise to sengoku-daimyo.

Edo period

The Battle of Sekigahara in 1600 marked the beginning of the Edo period. Shōgun Tokugawa Ieyasu reorganized roughly 200 daimyo and their territories into han, which were assessed by rice production. Those heading han assessed at 10,000 koku (50,000 bushels) or more were considered daimyo. Ieyasu also categorized the daimyo according to their relation to the ruling Tokugawa family: the shinpan were related to the Tokugawa; the fudai had been vassals of the Tokugawa or allies in battle; and the tozama had not allied with the Tokugawa before the battle (did not necessarily fight against the Tokugawa).

The shinpan were collaterals of Ieyasu, such as the Matsudaira, or descendants of Ieyasu other than in the main line of succession. Several shinpan, including the Tokugawa of Owari (Nagoya), Kii (Wakayama), and Mito, as well as the Matsudaira of Fukui and Aizu, held large han.

A few fudai daimyo, such as the Ii of Hikone, held large han, but many were small. The shogunate placed many fudai at strategic locations to guard the trade routes and the approaches to Edo. Also, many fudai daimyo took positions in the Edo shogunate, some rising to the position of rōjū. The fact that fudai daimyo could hold government positions while tozama in general, could not was a main difference between the two.

Tozama daimyo held mostly large fiefs far away from the capital, with e.g. the Kaga han of Ishikawa Prefecture, headed by the Maeda clan, assessed at 1,000,000 koku. Other famous tozama clans included the Mori of Chōshū, the Shimazu of Satsuma, the Date of Sendai, the Uesugi of Yonezawa, and the Hachisuka of Awa. Initially, the Tokugawa regarded them as potentially rebellious, but for most of the Edo period, marriages between the Tokugawa and the tozama, as well as control policies such as sankin-kōtai, resulted in peaceful relations.

Daimyo were required to maintain residences in Edo as well as their fiefs, and to move periodically between Edo and their fiefs, typically spending alternate years in each place, in a practice called sankin-kōtai.

After the Meiji Restoration

In 1869, the year after the Meiji Restoration, the daimyo, together with the kuge, formed a new aristocracy, the kazoku.[3][4] In 1871, the han were abolished, and prefectures were established.[5] In this year, around 200 daimyo returned their titles to the emperor, who consolidated their han into 75 prefectures.[6] Their military forces were also demobilized, with the daimyo and their samurai followers pensioned into retirement.[6] The move to abolish the feudal domains effectively ended the daimyo era in Japan. This was effectively carried out through the financial collapse of the feudal-domain governments, hampering their capability for resistance.[7]

In the wake of the changes, many daimyo remained in control of their lands, being appointed as prefectural governors; however, they were soon relieved of this duty and called en masse to Tokyo, thereby cutting off any independent base of power from which to potentially rebel. Despite this, members of former daimyo families remained prominent in government and society, and in some cases continue to remain prominent to the present day. For example, Morihiro Hosokawa, the former prime minister, is a descendant of the daimyo of Kumamoto.

References

- Katsuro, Hara (2009). An Introduction to the History of Japan. BiblioBazaar, LLC. p. 291. ISBN 1-110-78785-5.

- Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, entry for "daimyo"

- Norman, Herbert E. (2011). Japan's Emergence as a Modern State - 60th anniv. ed.: Political and Economic Problems of the Meiji Period. UBC Press. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-0-7748-4187-0.

- McLaren, Walter Wallace (2013). Political History of Japan During the Meiji Era, 1867-1912. Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-99549-1.

- Frédéric, Louis; Roth, Käthe (2002), Japan Encyclopedia, Harvard University Press Reference Library, Belknap, pp. 141–142, ISBN 9780674017535

- Nester, William R. (2016). The Foundation of Japanese Power: Continuities, Changes, Challenges: Continuities, Changes, Challenges. Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-48931-5.

- Huffman, James L. (2013). Modern Japan: An Encyclopedia of History, Culture, and Nationalism. Oxon: Routledge. p. 4. ISBN 9780815325253.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Daimio. |