Onsen

Onsen (温泉) is the Japanese name for a hot spring; the term also extends to cover the bathing facilities and traditional inns frequently situated around a hot spring. As a volcanically active country, Japan has thousands of onsens scattered throughout all of its major islands.[1]

Onsens come in many types and shapes, including outdoor (露天風呂 or 野天風呂, roten-buro or noten-buro) and indoor baths (内湯, uchiyu). Baths may be either publicly run by a municipality or privately, often as part of a hotel, ryokan, or bed and breakfast (民宿, minshuku).

The presence of an onsen is often indicated on signs and maps by the symbol ♨ or the kanji 湯 (yu, meaning "hot water"). Sometimes the simpler hiragana character ゆ (yu), understandable to younger children, is used.

Traditionally, onsens were located outdoors, although many inns have now built indoor bathing facilities as well. Nowadays, as most households have their own bath, the number of traditional public baths has decreased,[2] but the number of sightseeing hot spring towns has increased (most notable ones including Kinosaki Onsen, Togura Kamiyamada Onsen, and Akanko Onsen).[3] Onsens by definition use naturally hot water from geothermally heated springs. Onsens are different from sentō, indoor public bath houses where the baths are filled with heated tap water.

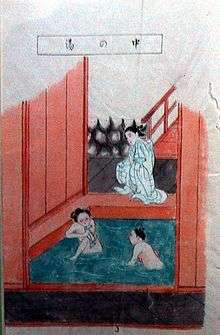

Mixed bathing

Traditionally, men and women bathed together at both onsens and sentōs, but gender separation has been enforced since the opening of Japan to the West during the Meiji Restoration. The practice had contributed at the time to Western ideas of the Japanese as an inferior race. Mixed bathing (混浴, kon'yoku) persists at some special onsen in rural areas of Japan,[4] which usually also provide the option of separate "women-only" baths or different hours for the two sexes. Men may cover their genitals with a small towel while out of the water, while women usually wrap their bodies in full-size towels. Children of either sex may be seen in both the men's and the women's baths. In some prefectures of Japan, including Tokyo, where nude mixed bathing is banned, people are required to wear swimsuits or yugi (湯着, yugi), or yuami-gi, which are specifically designed for bathing.[5]

Etiquette

Ensuring cleanliness

As at a sentō, at an onsen all guests are expected to wash and rinse themselves thoroughly before entering the hot water. Bathing stations are equipped with stools, faucets, wooden buckets, and toiletries such as soap and shampoo; nearly all onsen also provide removable shower heads for bathing convenience. Entering the onsen while still dirty or with traces of soap on the body is socially unacceptable.[lower-alpha 1]

Swimsuits

Bathers are not normally allowed to wear swimsuits in the baths. However, some modern onsen with a water park atmosphere require their guests to wear a swimming suit in their mixed baths.

Towels

Onsen guests generally bring a small towel with them to use as a wash cloth. The towel can also provide a modicum of modesty when walking between the washing area and the baths. Some onsen allow one to wear the towel into the baths, while others have posted signs prohibiting this, saying that it makes it harder to clean the bath. It is against the rules to immerse or dip towels in the onsen bath water, since this can be considered unclean. People normally set their towels off to the side of the water when enjoying the baths, or place their folded towels on top of their heads.

Noise

Onsen vary from quiet to noisy; some play piped music and often feature gushing fountains. Bathers will engage in conversation in this relaxed situation. There are usually prohibitions against rowdiness in the washing and bathing areas; However a small amount of excess energy and splashing around is usually tolerated from children.

Tattoos

By 2015, around half (56%) of onsen operators had banned bathers with tattoos from using their facilities.[6][7][8] The original reason for the tattoo ban was to keep out Yakuza and members of other crime gangs who traditionally have elaborate full-body decoration.[9]

However, tattoo-friendly onsen do exist.[10] A 2015 study by the Japan National Tourism Organisation found that more than 30% of onsen operators at hotels and inns across the country will not turn someone with a tattoo away; another 13% said they would grant access to a tattooed guest under certain conditions, such as having the tattoo covered up.[6] Some towns have many tattoo-friendly onsens that do not require guests to cover them up. Two such towns are Kinosaki Onsen in Hyōgo and Beppu Onsen in Ōita.[11]

With the increase in foreign customers due to growing tourism, some onsens that previously banned tattoos are loosening their rules to allow guests with small tattoos to enter, provided they cover their tattoos with a patch or sticking plaster.[6][12]

Therapy

The volcanic nature of Japan provides plenty of springs. When the onsen water contains distinctive minerals or chemicals, the onsen establishments typically display what type of water it is.[13]

Some examples of types of onsen include:

- Sulphur onsen (硫黄泉, iō-sen)

- Sodium chloride onsen (ナトリウム泉, natoriumu-sen)

- Hydrogen carbonate onsen (炭酸泉, tansan-sen)

- Iron onsen (鉄泉, tetsu-sen)

- Ordinary onsen (単純泉, tanjyun-sen)

Risks

Although millions of Japanese bathe in onsens every year with few noticeable side effects, there are still potential side effects to onsen usage, such as aggravating high blood pressure or heart disease.[14]

Legionella bacteria have been found in some onsens with poor sanitation.[15][16] Revelations of poor sanitary practices at some onsens have led to improved regulation by hot-spring communities to maintain their reputation.[17]

There have been reports of infectious disease found in hot bodies of water worldwide, such as various Naegleria species.[18] While studies have found the presence of Naegleria in hot spring waters, the worrisome Naegleria fowleri amoeba has not been identified.[18] Nevertheless, fewer than five cases have been seen historically in Japan, although not conclusively linked to onsen exposure.[19]

Many onsens display notices reminding anyone with open cuts, sores, or lesions not to bathe. Additionally, in recent years onsens are increasingly adding chlorine to their waters to prevent infection, although many onsen purists seek natural, unchlorinated onsens that do not recycle their water but instead clean the baths daily.[17] These precautions as well as proper onsen usage (i.e. not placing the head underwater, washing thoroughly before entering the bath) greatly reduce any overall risk to bathers.

Selected onsen

.jpg)

- Akagi, Gunma

- Akayu, Yamagata

- Arima Onsen, Kobe, Hyōgo

- Asamushi Onsen, Aomori Prefecture

- Aso, Kumamoto, a famous onsen area alongside Mount Aso, an active volcano

- Atami Onsen, Atami, Shizuoka, major onsen resort town near Tokyo

- Awara Onsen, Awara, Fukui Prefecture

- Awazu Onsen, Komatsu, Ishikawa

- Beppu Onsen, Beppu, Ōita Prefecture, famous for its multi-coloured baths

- Dake Onsen, Nihonmatsu, Fukushima

- Dōgo Onsen, Ehime Prefecture

- Funaoka Onsen, Kyoto

- Furofushi Onsen, Aomori Prefecture

- Futamata, Hokkaidō

- Gero Onsen, Gero, Gifu, famous for its free open bath on riverbank of Hida River

- Getō Onsen, Iwate Prefecture

- Ginzan Onsen, Obanazawa, Yamagata

- Hakone, Kanagawa, famous onsen resort town near Tokyo

- Hanamaki, Iwate

- Hirayu Onsen, Takayama, Gifu

- Hokkawa Onsen, Shizuoka

- Ibusuki Onsen, Kagoshima Prefecture

- Iizaka Onsen, Fukushima

- Ikaho Onsen, Ikaho, Gunma

- Itō, Shizuoka

- Iwaki Yumoto Onsen, Fukushima Prefecture

- Iwamuro, Niigata, famous for onsen since the Edo period

- Jigokudani, Nagano Prefecture

- Jōzankei Onsen, Hokkaido

- Kaike Onsen, Yonago, Tottori

- Kakeyu Onsen, Nagano

- Kanzanji Onsen, Shizuoka

- Katayamazu Onsen, Kaga, Ishikawa

- Kawayu Onsen, Tanabe, Wakayama

- Kindaichi Onsen, Iwate

- Kinosaki, Hyōgo

- Kinugawa Onsen, Tochigi

- Kurokawa Onsen, Aso, Kumamoto Prefecture

- Kusatsu Onsen, Gunma Prefecture

- Misasa Onsen, Misasa, Tottori Prefecture

- Nagaragawa Onsen, Gifu, Gifu

- Nanki-Katsuura Onsen, Nachikatsuura, Wakayama

- Nanki-Shirahama Onsen, Shirahama, Wakayama Prefecture

- Naoshima, Kagawa Prefecture

- Naruko, Miyagi

- Noboribetsu, Hokkaido

- Nuruyu Onsen, Kumamoto Prefecture

- Nyūtō Onsen, Akita Prefecture

- Obama Onsen, Nagasaki Prefecture, the hottest Japanese hot spring (105 °C or 221 °F)

- Onneyu Onsen, Hokkaido

- Ōfuka Onsen, Akita

- Ryujin Onsen, Tanabe, Wakayama, one of Japan's famous three beautifying onsen

- Sabakoyu Onsen, Fukushima Prefecture, the oldest community onsen in Japan

- Sakunami Onsen, Miyagi

- Sawatari, Gunma Prefecture

- Senami Onsen, Niigata Prefecture

- Shima Onsen, Gunma Prefecture

- Shimabara, Nagasaki

- Shimobe Onsen, Yamanashi Prefecture

- Shiobara Onsen, Tochigi Prefecture

- Shuzenji Onsen, Shizuoka Prefecture

- Sōunkyo Onsen, Hokkaido

- Sukayu Onsen, Aomori Prefecture

- Sumatakyō Onsen, Shizuoka Prefecture

- Suwa, Nagano Prefecture

- Takanoyu Onsen, Akita Prefecture

- Takaragawa, Gunma, one of the largest outdoor mixed baths in Japan

- Takarazuka, Hyōgo

- Tara, Saga

- Tōyako, Hokkaidō

- Tsubame Onsen, Niigata - famous for its free open mixed onsen

- Tsuchiyu Onsen, Fukushima Prefecture

- Tsukioka Onsen, Niigata, Niigata Prefecture

- Tsurumaki Onsen, Kanagawa

- Unazuki Onsen, Kurobe, Toyama Prefecture

- Wakura Onsen, Nanao, Ishikawa Prefecture

- Yamanaka Onsen, Kaga, Ishikawa

- Yamashiro Onsen, Kaga, Ishikawa

- Yubara Onsen, Okayama Prefecture, one of the largest mixed baths at the foot of Yubara dam

- Yudanaka Onsen, Nagano Prefecture

- Yufuin, Ōita Prefecture

- Yugawara, Kanagawa Prefecture

- Yumura Onsen (Yumura Onsen), (Shin'onsen, Hyōgo)

- Yunogo Onsen, Okayama Prefecture

- Yunokawa Onsen, Hokkaido

- Yunomine Onsen, Tanabe, Wakayama, site of the UNESCO World Heritage Tsuboyu bath

- Yuzawa, Niigata

- Zaō Onsen, Yamagata Prefecture

See also

- Ashiyu

- Balneotherapy

- Furo

- Public bathing

- Sauna

- Taiwanese hot springs

- Three Ancient Springs

- Turkish bath

- Onsen portal at the Japanese Wikipedia (in Japanese)

Notes

- In very isolated onsen, where there is no possibility to use soap before entering in the bath, onsen users are expected to at least rinse their body with the water of the bath before entering it.

References

- Nakata, Hiroko (22 January 2008). "Japan's hot springs part of social, geologic, historic fabric". The Japan Times. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- "Public Baths in Japan". www.japan-guide.com. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- "[2018 Edition] 7 Select Onsen Hot Spring Areas Rising in Popularity among Foreign Tourists in Japan". WOW! JAPAN. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- "Japan's Konyoku (mixed gender) Onsen Best 100". Konyoku.org. Archived from the original on 3 January 2014. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- Hadfield, James (10 December 2016). "Last splash: Immodest Japanese tradition of mixed bathing may be on the verge of extinction". The Japan Times. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- Ryall, Julian (6 November 2015). "Japanese owners of famous 'onsen' hot springs soften their stance on tattoo ban to appease foreign visitors". Archived from the original on 17 January 2016.

- Thompson, Ashley (6 November 2012). "If you need to bring drugs to Japan, sort out the paperwork — or else". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on 19 July 2015.

- Xeni Jardin (22 December 2009). "Tattoo in Japan". Boing Boing. Archived from the original on 24 December 2009.

- Onsen Warnings and Hassles, archived from the original on 24 January 2016

- Thompson, Ashley (27 November 2012). "Ink doesn't always cause a stink at the onsen". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on 19 July 2015.

- https://travel.gaijinpot.com/japan-sightseeing-essentials/30-tattoo-friendly-onsen-in-japan/

- Lund, Evie (17 April 2015). "Onsen in Nagano will now welcome foreigners with tattoos, as long as they patch 'em up". Archived from the original on 14 December 2015.

- Serbulea, Mihaela; Payyappallimana, Unnikrishnan (2012). "Onsen (hot springs) in Japan—Transforming terrain into healing landscapes". Health & Place. 18 (6): 1366. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.06.020. PMID 22878276.

- "Hot Spring Treatment|Hot Spring Encyclopedia|ONSEN|BEPPU CITY|". City.beppu.oita.jp. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- H. Miyamoto; S. Jitsurong; R. Shiota; K. Maruta; S. Yoshida; E. Yabuuchi (1997). "Molecular determination of infection source of a sporadic Legionella pneumonia case associated with a hot spring bath". Microbiol Immunol. 41 (3): 197–202. doi:10.1111/j.1348-0421.1997.tb01190.x. PMID 9130230.

- Eiko Yabuuchi Kunio Agata (2004). "An outbreak of legionellosis in a new facility of hot spring Bath in Hiuga City". Kansenshogaku Zasshi. 78 (2): 90–98. ISSN 0387-5911. PMID 15103899.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Onsen: know what you're getting into". The Japan Times.

- Shinji Izumiyama; Kenji Yagita; Reiko Furushima-Shimogawara; Tokiko Asakura; Tatsuya Karasudani; Takuro Endō (July 2003). "Occurrence and Distribution of Naegleria Species in Thermal Waters in Japan". The Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 50 (s1): 514–5. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2003.tb00614.x. PMID 14736147.

- Yasuo Sugita; Teruhiko Fujii; Itsurou Hayashi; Takachika Aoki; Toshirō Yokoyama; Minoru Morimatsu; Toshihide Fukuma; Yoshiaki Takamiya (May 1999). "Primary amebic meningoencephalitis due to Naegleria fowleri: An autopsy case in Japan". Pathology International. 49 (5): 468–70. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1827.1999.00893.x. PMID 10417693.

Further reading

- Hotta, Anne, and Yoko Ishiguro. A Guide to Japanese Hot Springs. New York: Kodansha America, 1986. ISBN 0-87011-720-3.

- Fujinami, Kōichi. Hot Springs in Japan. Tokyo: Board of Tourist Industry, Japanese Government Railways; Maruzen Company, Ltd., 1936.

- Neff, Robert. Japan's Hidden Hot Springs. Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle, 1995. ISBN 0-8048-1949-1.

- Seki, Akihiko, and Elizabeth Heilman Brooke. The Japanese Spa: A Guide to Japan's Finest Ryokan and Onsen. Boston: Tuttle Publishing, 2005. ISBN 0-8048-3671-X. Reprinted as Ryokan: Japan's Finest Spas and Inns, 2007. ISBN 0-8048-3839-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hot springs of Japan. |

- Onsen Tipster A database of genuine onsen in Japan

- Sento Guide Guide to public baths in Japan

- OnsenJapan.net Interactive Google map with easy-to-read icons, pictures, and reviews

- Secret Onsen a database with more than 125 onsen all around Japan

- Japan Onsen A mountain onsen guide of the Japan Alps

.jpg)