Kido Takayoshi

Kido Takayoshi (木戸 孝允) (born Wada Kogorō (和田 小五郎); August 11, 1833 – May 26, 1877), also referred to as Kido Kōin (木戸 こういん), was a Japanese statesman of the Meiji Restoration. He was known as Katsura Kogorō (桂 小五郎) during the late Tokugawa period. He is considered as one of the three great nobles who led the Restoration.

Kido Takayoshi | |

|---|---|

木戸 孝允 | |

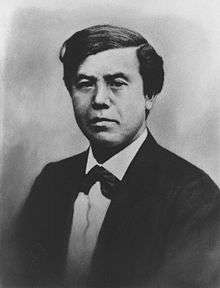

Kido Takayoshi in western dress (after Meiji Restoration) | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Wada Kogorō (和田 小五郎) August 11, 1833 Hagi, Chōshū Domain, Japan |

| Died | May 26, 1877 (aged 43) Kyoto, Japan |

| Resting place | Kyoto Ryozen Gokoku Shrine, Kyoto, Kyoto Prefecture, Japan |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Spouse(s) | Kido Matsuko ( m. 1868–1877) |

| Relations | Katsura Koroheiei (adoptive father) |

| Children | none |

| Mother | Seiko |

| Father | Wada Masakage |

| Relatives | Wada Suteko (half-sister) Wada Yaeko (half-sister) Kuribara Haruko (sister) Katsura Katsuzaburō (adopted son) Kido Shojirō (adopted son) Kido Takamasa (nephew) Kōichi Kido (grandnephew) |

| Residence | Kyoto, Japan |

| Alma mater | Meirinkan Shōka Sonjuku |

| Occupation | statesman |

| Profession | politics |

| Known for | One of the Three Great Nobles of the Restoration |

| Other names | Katsura Kogorō (桂 小五郎) Niibori Matsusuke (新堀 松輔) Kido Kanji (木戸 貫冶) Kido Junichirō (木戸 準一郎) Kido Kōin (木戸 孝允) |

Early life

Born Wada Kogorō in Hagi, Chōshū Domain (present-day Yamaguchi Prefecture), Japan as the son of Wada Masakage (和田 昌景), a samurai physician, and his second wife Seiko. In 1840, he was later adopted into the Katsura family at age seven and was known as Katsura Kogorō (桂 小五郎).[1]

The Katsura family's stipend was originally 150 koku, but due to the late nature of his adoption which took place as his supposed adoptive father Katsura Koroheiei was already on his deathbed, it was reduced to 90 koku. A year later in 1841, his adoptive mother also died, making Katsura Kogorō a head of the Katsura family, he later returned to his old home. In 1848, he lost his mother and elder half-sister Yaeko to illnesses.

Katsura was educated at Meirinkan, in which he later became increasing unhappy with and defied his father in order to be educated at Shōka Sonjuku in 1849, the academy of Yoshida Shōin, from whom he adopted the philosophy of Imperial loyalism. In 1851, his father had died.

In 1852, Katsura went to Edo to study swordsmanship, established ties with radical samurai from Mito domain, learned artillery techniques with Egawa Tarōzaemon, and (after observing the construction of foreign ships in Nagasaki and Shimoda), returned to Chōshū to supervise the construction of the domain's first western-style warship.

Overthrow of the Tokugawa

After 1858, Katsura Kogorō was based at the domain's Edo residence, where he served as liaison between the domain bureaucracy and radical elements among the young, lower-echelon Chōshū samurai who supported the Sonnō jōi movement. Coming under suspicion by the shogunate for his ties with Mito loyalists after the attempted assassination of Andō Nobumasa, he was transferred to Kyōto. However, while in Kyōto, he was unable to prevent the 30 September 1863 coup d'état by the forces of the Aizu and Satsuma domains, who drove the Chōshū forces out of the city.

Ikedaya incident

According to his personal diary regarding the Ikedaya incident, Katsura was at the loyalist meeting with the Ishin Shishi at the Ikedaya inn in the evening on July 8, 1864, he claimed that they had only met to discuss how to rescue Furutaka Shuntaro from the Shinsengumi. Katsura later left the inn earlier, before the attack by the Shinsengumi troops on that night.

However, there were rumors varied that Katsura was tipped off by his geisha lover Ikumatsu (幾松), that the Shinsengumi were coming for him and wisely chose not show up for the meeting, or that he climbed out the window of the upper floor of the inn during the attack by the Shinsengumi and escaped over the roofs.

He spent the next five days in hiding under Nijō Bridge along the Kamo River, posing as a beggar, his lover would brought him riceballs from the shop of the Chōshū merchant Imai Tarōemon and later aided in his escape.

Kinmon incident

Katsura was involved but not present in the Hamaguri Gate Rebellion on 20 August 1864, with the unsuccessful attempt to capture the Emperor Kōmei by the Chōshū forces at Hamaguri Gate in order to restore the Imperial household to its position of political supremacy, the Chōshū forces clashed with Aizu and Satsuma forces who led to the defense of the Imperial palace. During the attempt, the Chōshū rebels put Kyoto on fire, starting with the residence of the Takatsukasa family, and that of a Chōshū official.

The rebellion resulted in 28,000 houses being burnt down, with casualties of about 400 from the Chōshū forces, including his adopted son Katsuzaburō, and only 60 from Aizu and Satsuma forces, forcing Katsura into hiding again with his geisha lover. He would later used the name Niibori Matsusuke as an alias in 1865 to continue his work against the Tokugawa bakufu.

Satchō Alliance

After radical elements under Takasugi Shinsaku gained control of Chōshū politics, Katsura, under the new name Kido Junichirō (木戸 準一郎) was instrumental in establishing the Satchō Alliance with Saigō Takamori and Ōkubo Toshimichi through the mediation of Sakamoto Ryōma in 1866, which proved to be critical in the Boshin War and the subsequent Meiji Restoration. Around the same time, he adopted Shojirō, another nephew who was the second son of his younger sister, Kuribara Haruko, as his heir.

Meiji statesman

Following the overthrow of the Tokugawa bakufu in 1868, Kido claimed a large role in the establishment of the new Meiji government. As a san'yo (Imperial Advisor) he helped draft the Five Charter Oath, and initiated policies of centralization and modernization. He helped direct the Abolition of the han system. In August 1868, he had his lover Ikumatsu adopted into a samurai family of Okabe Tomitarō, and later made her his wife. He was later renamed to Kido Takayoshi (木戸 孝允) in 1869.

On 23 December 1871, he accompanied the Iwakura Mission on its round-the-world voyage to the United States and Europe, and was especially interested in Western educational systems and politics. On his return to Japan on 13 September 1873, he would become a strong advocate of the establishment of constitutional government. Realizing that Japan was not in any position to challenge the Western powers in its present state, he also returned to Japan just in time to prevent an invasion of Korea (Seikanron).

Kido lost his dominant position in the Meiji oligarchy to Ōkubo Toshimichi, and resigned from government in protest of the Taiwan Expedition of 1874, which he had strenuously opposed.[2]

Following the Osaka Conference of 1875, Kido agreed to return to the government, and became chairman of the Assembly of Prefectural Governors that the Ōsaka Conference had created. He was also responsible for the education of the young Emperor Meiji.

Death

During the middle of Satsuma Rebellion of 1877, he died of an illness that had been plaguing him for a long time, which consisted of a combination of some form of mental disease and physical exhaustion, years of excessive alcohol consumption as well as an illness assumed to be tuberculosis or beriberi. He was buried at the Kyoto Ryozen Gokoku Shrine, Kyoto, Japan.

Legacy

His heir Shojirō, who had studied for ten years in England before returning to Japan in 1882, however died of illness on the ship during the return journey near Ceylon. Kuribara Hikotarō, another Kido's nephew and Shojirō's eldest brother, succeeded him as the new heir of the Kido family on 18 November 1884 and was known as the Marquis Kido Takamasa.

Kido Takayoshi was enshrined as the Shinto deity of scholarship and the martial arts at the Kido Shrine in about 1886[3] at Kido Park, Yamaguchi, Yamaguchi Prefecture, Japan.[4]

His widow Matsuko survived him and died in 1887 at the age of 43.

Kido's diary reveals an intense internal conflict between his loyalty to his home domain, Chōshū, and the greater interest of the country. He wrote often of having to fight rumors at home that he had betrayed his old friends; the idea of a nation was still relatively new in Japan and so the majority of samurai cared more for securing privileges for their own domain.

Together with Saigō Takamori and Ōkubo Toshimichi, he was known as the Ishin-no-Sanketsu (維新の三傑), which means, roughly, "Three Great Nobles of the Restoration". His younger sister's grandson was Tokyo politician Kōichi Kido (木戸 幸一).

In popular culture

Kido, referred to by his initial name Katsura Kogorō, was among the historical personalities present in the manga and anime Rurouni Kenshin by Nobuhiro Watsuki, as well as its OVA adaptation Tsuiokuhen (Trust & Betrayal). While still portrayed as a ruthless radical leader of the Chōshū clan, he serves as a benevolent mentor of sorts to the young Kenshin Himura, who worked under him as the Hitokiri Battōsai. He nonetheless regrets having Kenshin do the dirty work for him after Kenshin's affair with Tomoe Yukishiro (in Tsuiokuhen, he actively encouraged Tomoe to stand by Kenshin to serve as a calming influence), which ultimately boiled over into a clash with her ties as a shogunate agent and her will to live life anew in the new era of modern Meiji Japan. He is voiced by Tomokazu Seki.

Japanese actor Ken Ishiguro portrayed him in the 2004 jdorama Shinsengumi! as the old time friend of the protagonist Kondo Isami and also the leader of the Chōshū han.

Japanese actor Shōsuke Tanihara portrayed him in the 2009 jdorama Ryōmaden as the leader of the Chōshū han.

He is also the basis for the character of Katsura Kotarou in the manga and anime Gin Tama by Hideaki Sorachi.

He also appears in the video game Ryu ga Gotoku Ishin, portrayed by the Yakuza character Shun Akiyama, and voiced by Koichi Yamadera.

Honours

- Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun (May 24, 1877)

- Junior First Rank (May 22, 1901; posthumous)

Gallery of Former Residence of Kido Takayoshi at Hagi, Japan

House of Takayoshi Kido

House of Takayoshi Kido Gate of former residence of Kido Takayoshi

Gate of former residence of Kido Takayoshi Garden of former residence of Kido Takayoshi

Garden of former residence of Kido Takayoshi

Childhood room of Kido Takayoshi

Childhood room of Kido Takayoshi Edoya Lane near former residence of Kido Takayoshi

Edoya Lane near former residence of Kido Takayoshi

Notes

- Ellen P. Conant (2006). Challenging Past And Present: The Metamorphosis of Nineteenth-Century Japanese Art. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 178–180. ISBN 978-0-8248-2937-7.

- Kokushi daijiten Vol. 4, pp. 170–171.

- "Kido Shrine | Yamaguchi City - a strategic base of the Meiji Restoration. | Traveling website of Yamaguchi City - a city of celebrating the 150 year anniversary of the Meiji Restoration". ishin150-yamaguchi.com (in Japanese). Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- "Kido Park / maple | YAMAGUCHI JAPAN TRAVEL GUIDE". www.visit-jy.com. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

Reference and further reading

- Akamatsu, Paul. Meiji 1868: Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Japan. Trans. Miriam Kochan. New York: Harper & Row, 1972.

- Beasley, William G. (1972). The Meiji Restoration. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804708159; OCLC 579232

- Beasley, W. G. The Rise of Modern Japan: Political, Economic and Social Change Since 1850. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1995.

- Craig, Albert M. Chōshū in the Meiji Restoration. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1961. OCLC 482814571

- Jansen, Marius B. and Gilbert Rozman, eds. (1986). Japan in Transition: from Tokugawa to Meiji. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691054599; OCLC 12311985

- Kido, Takayoshi. (1983). The Diary of Kido Takayoshi (Sidney DeVere Brown and Akiko Hirota, translators), Vol. I (1868–1871), Vol. II (1871–1874), Vol. III (1874–1877). Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press.

- Nish, Ian. (1998) The Iwakura Mission to America and Europe: A New Assessment. Richmond, Surrey: Japan Library. ISBN 9781873410844; ISBN 0415471796; OCLC 40410662

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kido Takayoshi. |

- Selected Diary Entries of Kido

- National Diet Library photo & bio

- Meiji Dignitaries is a portrait of Takayoshi and others from 1877