Ōshima Joun

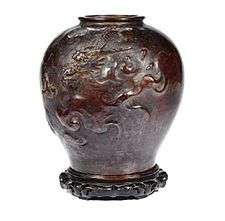

Ōshima Joun[1] (大島如雲, Ōshima Joun, 1858 – 1940) was a Japanese sculptor and artist, noted for his great artistry and skill in bronze casting.

Career

Joun was born to a family of metalworkers and was famous for his skill in casting bronze. He was the son of Ōshima Takajiro, whose own father Ōshima Yasubei was the first metal craftsman in the family.[2] He was a professor at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts (東京美術学校 Tōkyō Bijutsu Gakkō; name changed in 2008 to Tokyo University of the Arts) from 1887 until 1932.

His studio, Sanseisha — run with his brother Ōshima Yasutaro, also a skilled artist — was very successful and at one point employed 11 assistants. During the period 1875 to 1879, the studio "produced some of the finest bronzes ever produced in Japan."[3] Old labels on Joun's tomobako (wooden storage boxes) suggest that the well-established Ginza (in Tokyo) purveyor of silver and other fine metal wares Miyamoto-Shoko (established 1880) may also have handled some of Joun's sales.[4]

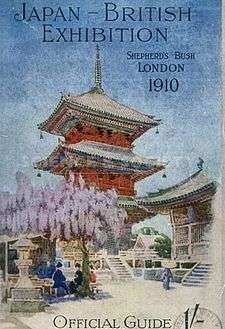

Many of Joun's students (Ryūki, Chōkichi Suzuki (see mention in Victoria and Albert Museum), Sessei Okazaki, Kumazō Hasegawa, Gorosaburō Kanaya, Eisuke Jomi) went on to achieve distinction of their own.[5] He exhibited at the 2nd National Industrial Exposition in 1881, and at the Paris Exposition Universelle (1900), and the Japan-British Exhibition of 1910.[6]

Ōshima Joun died in Tokyo on January 4, 1940, at 83 years old.[7]

Art-name

There appears to be some debate about the correct attribution of the gō (or art-name) Ōshima Joun to either Ōshima Katsujiro[8] or his brother Ōshima Yasutaro.[9] Both were noted artists in metal, and there was another gō in use at the time, Ōshima Shōkaku[3] (var. Shokaken[2]), but there appears to be confusion about which brother should properly be associated with each of these art names. The Oshima Joun obituary at the National Research Institute for Cultural Properties appears to prefer Ōshima Katsujiro taking Ōshima Joun,[7] and Francis Brinkley's 1902 Japan: Its History, Arts, and Literature,[10] also asserts that Ōshima Katsujiro used the Ōshima Joun gō, but an authoritative history of the matter is needed.

Notes

- Ōshima is the surname. Within text in English, Ōshima is sometimes rendered “Oshima” (without the long "o" signifier, which is usually an artifact of older printing conventions, and not of different pronunciation); and the full name is often written in reverse order, with given name first and family name last.

- Meiji no Takara: Treasures of Imperial Japan:Metalwork Part II (The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Japanese Art) Entry no. 102. "Oshima Joun." 1995. London: Kibo Foundation.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed., 1911. s.v. "Japan/Bronze Casting." Cambridge:University Press.

- "Miyamoto Shoko's website. Accessed 04-30-2013" (in Japanese). Retrieved 2013-04-30. An attempt around this same date to confirm directly with Miyamoto-Shoko details of this relationship was unsuccessful because, according to Miyamoto-Shoko, most of their pre-WWII records were lost during that war.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed., 1911. s.v. "Japan/Bronze Casting." Cambridge:University Press."

- "Kagedo Japanese Art Gallery - Meiji-Taisho Art online". Kagedo.com. Archived from the original on 2014-07-01. Retrieved 2012-05-07.

- "Obituary at National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, Tokyo. Accessed 12-11-2010" (in Japanese). Tobunken.go.jp. Retrieved 2012-05-07.

- As one of the oldest English language sources available on this name attribution issue, the authors of the Encyclopædia Britannica of 1911 argue for Katsujiro in Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed., 1911. s.v. "Japan/Bronze Casting." Cambridge:University Press. Similarly, in 1991, Impey and Fairley argue for Katsujiro in The Dragon King of the Sea, 1991. Oxford:Ashmolean Museum.

- As possibly the most authoritative modern source in English, Fairley, Harris, and Impey argue for Yasutaro in Meiji no Takara: Treasures of Imperial Japan:Metalwork Part II (The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Japanese Art) Entry no. 102. "Oshima Joun." 1995. London: Kibo Foundation.

- Captain F. Brinkley. Japan: Its History, Arts, and Literature. [Oriental Series, Volume VII.] (Boston and Tokyo: JB Millet Company. 1902. Pp. 144-145, and P. 20 of Appendix: Names, Periods, and Schools of Japanese Pictorial Artists.)

References

- Meiji no Takara: Treasures of Imperial Japan:Metalwork Part II (The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Japanese Art) Entry no. 102. "Oshima Joun." 1995. London: Kibo Foundation.

- Clark, John. 2001. Japanese Exchanges in Art, 1850s to 1930s with Britain, continental Europe, and the USA: Papers and Research Materials Sydney: Power Publications, 89, 334–335.

- Oliver Impey and Malcolm Fairley. 1911. The Dragon King of the Sea, Oxford:Ashmolean Museum.

External links

- Ōshima Joun holdings at the University Art Museum of Tokyo University of the Arts

- Instructors Ōshima Joun (Jo'un Oshima) and Sessei Okazaki are listed in this too-brief history paragraph of the Metal Casting Department of the Tokyo University of the Arts as leaders of the arts and crafts movement in Japan

- Miyamoto-Shoko Silversmiths, Tokyo

- Ōshima Joun on Artnet.com

- Ōshima Joun at Bonhams