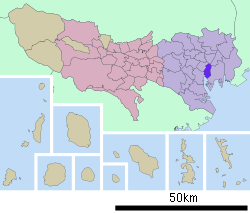

Ginza

Ginza (/ˈɡɪnzə/ GHIN-zə; Japanese: 銀座 [ɡindza]) is a district of Chūō, Tokyo, located south of Yaesu and Kyōbashi, west of Tsukiji, east of Yūrakuchō and Uchisaiwaichō, and north of Shinbashi. It is a popular upscale shopping area of Tokyo, with numerous internationally renowned department stores, boutiques, restaurants and coffeehouses located in its vicinity. It is considered to be one of the most expensive, elegant, and luxurious streets in the world.

Ginza 銀座 | |

|---|---|

District | |

Ginza's Wako store in 2018 | |

| Coordinates: 35°40′16″N 139°45′54″E | |

| Country | |

| City | |

| Ward | |

Ginza was a part of the old Kyobashi ward of Tokyo City, which, together with Nihonbashi and Kanda, formed the core of Shitamachi,[1] the original downtown center of Edo-Tokyo.

History

Ginza was built upon a former swamp that was filled in during the 16th century. The name Ginza comes after the establishment of a silver-coin mint established there in 1612, during the Edo period.[2]

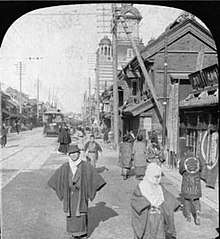

After a devastating fire in 1872 burned down most of the area,[2] the Meiji government designated the Ginza area as a "model of modernization." The government planned the construction of fireproof brick buildings and larger, better streets connecting Shimbashi Station all the way to the foreign concession in Tsukiji.

Soon after the fire, redevelopment schemes were prepared by Colin Alexander McVean[3] a chief surveyor of the Public Works under direction of Yamao Yozo, but execution designs were provided by the Irish-born engineer Thomas Waters;[2] the Bureau of Construction of the Ministry of Finance was in charge of construction. In the following year, a Western-style shopping promenade on the street from the Shinbashi bridge to the Kyōbashi bridge in the southwestern part of Chūō with two- and three-story Georgian brick buildings was completed.

These "bricktown" buildings were initially offered for sale and later were leased, but the high rent prevented many of them from being permanently occupied. Moreover, the construction was not adapted to the climate, and the bold design contrasted the traditional Japanese notion of home construction. The new Ginza was not popular with visiting foreigners, who were looking for a more Edo-styled city. Isabella Bird visited in 1878 and in 1880 implied that Ginza was less like an Oriental city than like the outskirts of Chicago or Melbourne. Philip Terry, the English writer of tour guides, likened it to Broadway, not in a positive sense.[4]

Nevertheless, the area flourished as a symbol of "civilization and enlightenment" thanks to the presence of newspapers and magazine companies, which helped spread the latest trends of the day. The area was also known for its window displays, an example of modern marketing techniques. Everyone visited so the custom of "killing time in Ginza" developed strongly between the two world wars.[4]

Most of these European-style buildings disappeared, but some older buildings still remain, most famously the Wakō building with the now-iconic Hattori Clock Tower. The building and the clock tower were originally built by Kintarō Hattori, the founder of Seiko.

Its recent history has seen it as a prominent outpost of Western luxury shops. Ginza is a popular destination on weekends, when the main north-south artery is closed to traffic since the 1960s, under governor Ryokichi Minobe.

Economy

Many leading fashion houses' flagship stores are located here, in the area with the highest concentration of Western shops in Tokyo. It is one of two locations in Tokyo considered by Chevalier and Mazzalovo to be the best locations for a luxury goods store.[5] Prominent high-end retailers include the American company Carolina Herrera New York, French companies Chanel, Dior, Louis Vuitton and Saint Laurent, Italian company Gucci and Austrian brands Swarovski and Riedel.

Flagship electronic retail stores like the Sony showroom (which closed in 2017 and new building would open in 2022) and the Apple Store are also here (Ginza 2 chome). The electronics company, Ricoh is headquartered in the Ricoh Building in Ginza.[6] The neighborhood is a major shopping district. It is home to Wako department store, which is located in a building dating from 1894. The building has a clock tower. There are many department stores in the area, including Hankyu, Seibu, and Matsuya, in which there are many shops: grocery stores, restaurants, women and men clothes, sports wear, and jewellers etc. There are also art galleries.[2] Kabuki-za is the theater for kabuki, one of Japanese traditional playing, and locates on between Ginza and Tsukiji. The building was opened in 1889 and has been reconstructed several times because of war and fire. The present building was built in 2013.

Mitsukoshi department store at Ginza. As a symbol, there are two lions at the entrance of department, which is popular place for meeting.

Mitsukoshi department store at Ginza. As a symbol, there are two lions at the entrance of department, which is popular place for meeting. The Sony Building and intersection at dusk. The Sony building was demolished in 2017, and the new Sony building is scheduled for completion and opening in fall 2022.

The Sony Building and intersection at dusk. The Sony building was demolished in 2017, and the new Sony building is scheduled for completion and opening in fall 2022. Kabuki-za theater Kabukiza locates between Ginza and Tsukiji. From Mitsukoshi, it takes about 15 minutes with walking.

Kabuki-za theater Kabukiza locates between Ginza and Tsukiji. From Mitsukoshi, it takes about 15 minutes with walking.- Taimei Elementary School

- Tokyu Plaza Ginza In this shopping center, there is a duty-free shop for visitor from other countries.

Ginza Six shopping complex This shopping center is the newest one in Ginza. Dior Cafe locates in this building.

Ginza Six shopping complex This shopping center is the newest one in Ginza. Dior Cafe locates in this building. Ginza at night

Ginza at night Ginza in the rain

Ginza in the rain Ginza in afternoon

Ginza in afternoon

Pedestrianization

Each Saturday and Sunday, from 12:00 p.m. until 5:00 p.m., the main street through Ginza is closed off to road traffic, allowing people to walk freely. This is called Hokōsha Tengoku (歩行者天国) or Hokoten for short, literally meaning "pedestrian heaven". There are some people who do street performance such as magic and playing instruments. As a famous photo spot, some cats sleep on signs, where people can put their own cats onto these signs. The location where cats are is different depending on the date.

Subway stations

- Ginza Station (銀座駅) (Tokyo Metro Hibiya Line, Tokyo Metro Ginza Line, Tokyo Metro Marunouchi Line)

- Ginza-itchōme Station (銀座一丁目駅) (Tokyo Metro Yūrakuchō Line)

- Higashi-Ginza Station (東銀座駅) (Tokyo Metro Hibiya Line, Toei Asakusa Line)

Other stations near Ginza:

- Yurakucho Station (有楽町駅) Tokyo Metro Yurakucho line, JR Yamanote line, JR Keihin tohoku line

- Hibiya Station (日比谷駅)Tokyo Metro Hibiya line, Tokyo Metro Chiyoda line, Toei Mita line

- Shinbashi Station (新橋駅) Tokyo Metro Ginza line, Toei Asakusa line, JR Yamanote line, JR Keihin tohoku line

Ginza Station, Yurakucho Station, Hibiya Station are connected underground.

See also

- Asakusa

- Omotesando

- List of upscale shopping districts

- Tourism in Japan

References

- Kokushi Daijiten Iinkai. Kokushi Daijiten (in Japanese). Vol. 4, page 842 (1983 ed.).

- Dk eyewitness travel guide japan. [S.l.]: Dk Publishing. pp. 66–67. ISBN 9780756694739.

- Hideo Izumida, Reconsideration of Foundation of Engineering Education by Ministry of Public Works, Journal of Architectural Institute of Japan, February 2016, Vol.81-No.720, pp.478-488.

- Tokyo from Edo to Showa. Tuttle Publishing. p. 75. ISBN 9784805310243.

- Chevalier, Michel; Mazzalovo, Gerald (2012). Luxury Brand Management. Singapore: John Wiley & Sons. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-118-17176-9. The other prime location is Omotesandō.

- "Company Data Richo's building is one of symbol of Ginza. Archived 2009-02-05 at the Wayback Machine." Ricoh. Retrieved on January 13, 2009.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ginza. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Ginza. |

- Tokyo Essentials: Ginza

- Ginza Concierge

- Ginza Architecture and Map