Government of Japan

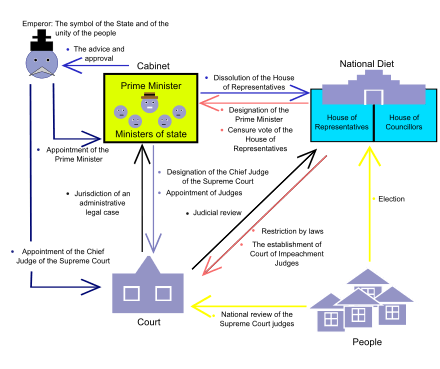

The Government of Japan is a constitutional monarchy in which the power of the Emperor is limited and is relegated primarily to ceremonial duties, based on popular sovereignty. The Government is divided into three branches: the Legislative branch, the Executive branch, and the Judicial branch.

| |

| Polity type | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

|---|---|

| Constitution | Constitution of Japan |

| Legislative branch | |

| Name | National Diet |

| Meeting place | National Diet Building |

| Upper house | |

| Name | House of Councillors |

| Lower house | |

| Name | House of Representatives |

| Executive branch | |

| Head of State | |

| Title | Emperor |

| Currently | Naruhito |

| Head of Government | |

| Title | Prime Minister |

| Currently | Shinzo Abe |

| Appointer | Emperor |

| Cabinet | |

| Name | Cabinet of Japan |

| Leader | Prime Minister |

| Appointer | Prime Minister |

| Headquarters | Prime Minister's Official Residence |

| Judicial branch | |

| Supreme Court of Japan | |

| Seat | Chiyoda |

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Japan |

|

|

|

|

| Government of Japan | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japanese name | |||||

| Kanji | 日本国政府 | ||||

| Hiragana | にっぽんこくせいふ(formal) にほんこくせいふ(informal) | ||||

| |||||

The Government runs under the framework established by the Constitution of Japan, adopted in 1947. It is a unitary state, containing forty-seven administrative divisions, with the Emperor as its head of state.[1] His role is ceremonial and he has no powers related to Government.[2] Instead, it is the Cabinet, comprising the Ministers of State and the Prime Minister, that directs and controls the Government and the civil service. The Cabinet has the executive power and is formed by the Prime Minister, who is the head of government.[3][4] He or she is designated by the National Diet and appointed to office by the Emperor.[5][6]

The National Diet is the legislature, the organ of the Legislative branch. It is bicameral, consisting of two houses with the House of Councilors being the upper house, and the House of Representatives being the lower house. Its members are directly elected by the people, who are the source of sovereignty.[7] It is defined as the supreme organ of sovereignty in the Constitution. The Supreme Court and other inferior courts make up the Judicial branch and have all the judicial powers in the state. It has ultimate judicial authority to interpret the Japanese constitution and the power of judicial review. They are independent from the executive and the legislative branches.[8] Judges are designated or appointed by the Cabinet and never removed by the executive and the legislature except the Impeachment.

History

Prior to the Meiji Restoration, Japan was ruled by the government of a successive military shōguns. During this period, effective power of the government resided in the Shōgun, who officially ruled the country in the name of the Emperor.[9] The Shoguns were the hereditary military governors, with their modern rank equivalent to a generalissimo. Although the Emperor was the sovereign who appointed the Shōgun, his roles were ceremonial and he took no part in governing the country.[10] This is often compared to the present role of the Emperor, whose official role is to appoint the Prime Minister.[11]

The Meiji Restoration in 1872 led to the resignation of Shōgun Tokugawa Yoshinobu, agreeing to "be the instrument for carrying out" the Emperor's orders.[12] This event restored the country to Imperial rule and the proclamation of the Empire of Japan. In 1889, the Meiji Constitution was adopted in a move to strengthen Japan to the level of western nations, resulting in the first parliamentary system in Asia.[13] It provided a form of mixed constitutional-absolute monarchy, with an independent judiciary, based on the Prussian model of the time.[14]

A new aristocracy known as the kazoku was established. It merged the ancient court nobility of the Heian period, the kuge, and the former daimyōs, feudal lords subordinate to the shōgun.[15] It also established the Imperial Diet, consisting of the House of Representatives and the House of Peers. Members of the House of Peers were made up of the Imperial Family, the Kazoku, and those nominated by the Emperor,[16] while members of the House of Representatives were elected by direct male suffrage.[17] Despite clear distinctions between powers of the executive branch and the Emperor in the Meiji Constitution, ambiguity and contradictions in the Constitution eventually led to a political crisis.[18] It also devalued the notion of civilian control over the military, which meant that the military could develop and exercise a great influence on politics.[19]

Following the end of World War II, the present Constitution of Japan was adopted. It replaced the previous Imperial rule with a form of Western-style liberal democracy.[20]

As of 2020, the Japan Research Institute found the national government is mostly analog, because only 7.5% (4,000 of the 55,000) administrative procedures can be completed entirely online. The rate is 7.8% at the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, 8% at the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, and only 1.3% at the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries.[21]

The Emperor

The Emperor of Japan (天皇) is the head of the Imperial Family and the ceremonial head of state. He is defined by the Constitution to be "the symbol of the State and of the unity of the people".[7] However, he is not the nominal Chief Executive and he possesses only certain ceremonially important powers. He has no real powers related to the Government as stated clearly in article 4 of the Constitution.[22]

Article 6 of the Constitution of Japan delegates the Emperor the following ceremonial roles:

- Appointment of the Prime Minister as designated by the Diet.

- Appointment of the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court as designated by the Cabinet.

While the Cabinet is the source of executive power and most of its power is exercised directly by the Prime Minister, several of its powers are exercised by the Emperor. The powers exercised via the Emperor, as stipulated by Article 7 of the Constitution, are:

- Promulgation of amendments of the constitution, laws, cabinet orders and treaties.

- Convocation of the Diet.

- Dissolution of the House of Representatives.

- Proclamation of general election of members of the Diet.

- Attestation of the appointment and dismissal of Ministers of State and other officials as provided for by law, and of full powers and credentials of Ambassadors and Ministers.

- Attestation of general and special amnesty, commutation of punishment, reprieve, and restoration of rights.

- Awarding of honors.

- Attestation of instruments of ratification and other diplomatic documents as provided for by law.

- Receiving foreign ambassadors and ministers.

- Performance of ceremonial functions.

The Emperor is known to hold the nominal ceremonial authority. For example, the Emperor is the only person that has the authority to appoint the Prime Minister, even though the Diet has the power to designate the person fitted for the position. One such example can be prominently seen in the 2009 Dissolution of the House of Representatives. The House was expected to be dissolved on the advice of the Prime Minister, but was temporarily unable to do so for the next general election, as both the Emperor and Empress were visiting Canada.[23][24]

In this manner, the Emperor's modern role is often compared to those of the Shogunate period and much of Japan's history, whereby the Emperor held great symbolic authority but had little political power; which is often held by others nominally appointed by the Emperor himself. Today, a legacy has somewhat continued for a retired Prime Minister who still wields considerable power, to be called a Shadow Shogun (闇将軍).[25]

Unlike his European counterparts, the Emperor is not the source of sovereign power and the government does not act under his name. Instead, the Emperor represents the State and appoints other high officials in the name of the State, in which the Japanese people hold sovereignty.[26] Article 5 of the Constitution, in accordance with the Imperial Household Law, allows a regency to be established in the Emperor's name, should the Emperor be unable to perform his duties.[27]

On November 20, 1989, the Supreme Court ruled it doesn’t have judicial power over the Emperor. [28]

The Imperial House of Japan is said to be the oldest continuing hereditary monarchy in the world.[29] According to the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki, Japan was founded by the Imperial House in 660 BC by Emperor Jimmu (神武天皇).[30] Emperor Jimmu was the first Emperor of Japan and the ancestor of all of the Emperors that followed.[31] He is, according to Japanese mythology, the direct descendant of Amaterasu (天照大御神), the sun goddess of the native Shinto religion, through Ninigi, his great-grandfather.[32][33]

The Current Emperor of Japan (今上天皇) is Naruhito. He was officially enthroned on May 1, 2019, following the abdication of his father.[34][35] He is styled as His Imperial Majesty (天皇陛下), and his reign bears the era name of Reiwa (令和). Fumihito is the heir presumptive to the Chrysanthemum Throne.

Executive

The Executive branch of Japan is headed by the Prime Minister. The Prime Minister is the head of the Cabinet, and is designated by the legislative organ, the National Diet.[5] The Cabinet consists of the Ministers of State and may be appointed or dismissed by the Prime Minister at any time.[4] Explicitly defined to be the source of executive power, it is in practice, however, mainly exercised by the Prime Minister. The practice of its powers is responsible to the Diet, and as a whole, should the Cabinet lose confidence and support to be in office by the Diet, the Diet may dismiss the Cabinet en masse with a motion of no confidence.[36]

Prime Minister

The Prime Minister of Japan (内閣総理大臣) is designated by the National Diet and serves a term of four years or less; with no limits imposed on the number of terms the Prime Minister may hold. The Prime Minister heads the Cabinet and exercises "control and supervision" of the executive branch, and is the head of government and commander-in-chief of the Japan Self-Defense Forces.[37] The Prime Minister is vested with the power to present bills to the Diet, to sign laws, to declare a state of emergency, and may also dissolve the Diet's House of Representatives at will.[38] He or she presides over the Cabinet and appoints, or dismisses, the other Cabinet ministers.[4]

Both houses of the National Diet designates the Prime Minister with a ballot cast under the run-off system. Under the Constitution, should both houses not agree on a common candidate, then a joint committee is allowed to be established to agree on the matter; specifically within a period of ten days, exclusive of the period of recess.[39] However, if both houses still do not agree to each other, the decision made by the House of Representatives is deemed to be that of the National Diet.[39] Upon designation, the Prime Minister is presented with their commission, and then formally appointed to office by the Emperor.[6]

As a candidate designated by the Diet, he or she is required to report to the Diet whenever demanded.[40] The Prime Minister must also be both a civilian and a member of either house of the Diet.[41]

| No. | Name (English) | Name (Japanese) | Gender | Took Office | Left Office | Term | Alma Mater |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Junichiro Koizumi | 小泉 純一郎 | Male | April 26, 2001 | September 26, 2006 | 5 Years | Keio University University College London |

| 2 | Shinzō Abe | 安倍 晋三 | Male | September 26, 2006 | September 26, 2007 | 1 Year | Seikei University |

| 3 | Yasuo Fukuda | 福田 康夫 | Male | September 26, 2007 | September 24, 2008 | 1 Year | Waseda University |

| 4 | Taro Aso | 麻生 太郎 | Male | September 24, 2008 | September 16, 2009 | 1 Year | Gakushuin University[42] |

| 5 | Yukio Hatoyama | 鳩山 由紀夫 | Male | September 16, 2009 | June 2, 2010 | 1 Year | University of Tokyo Stanford University |

| 6 | Naoto Kan | 菅 直人 | Male | June 8, 2010 | September 2, 2011 | 1 Year | Tokyo Institute of Technology |

| 7 | Yoshihiko Noda | 野田 佳彦 | Male | September 2, 2011 | December 26, 2012 | 1 Year | Waseda University |

| 8 | Shinzō Abe | 安倍 晋三 | Male | December 26, 2012 | Present | - | Seikei University |

※ As of October 14, 2018

The Cabinet

The Cabinet of Japan (内閣) consists of the Ministers of State and the Prime Minister. The members of the Cabinet are appointed by the Prime Minister, and under the Cabinet Law, the number of members of the Cabinet appointed, excluding the Prime Minister, must be fourteen or less, but may only be increased to nineteen should a special need arise.[43][44] Article 68 of the Constitution states that all members of the Cabinet must be civilians and the majority of them must be chosen from among the members of either house of the National Diet.[45] The precise wording leaves an opportunity for the Prime Minister to appoint some non-elected Diet officials.[46] The Cabinet is required to resign en masse while still continuing its functions, till the appointment of a new Prime Minister, when the following situation arises:

- The Diet's House of Representatives passes a non-confidence resolution, or rejects a confidence resolution, unless the House of Representatives is dissolved within the next ten (10) days.

- When there is a vacancy in the post of the Prime Minister, or upon the first convocation of the Diet after a general election of the members of the House of Representatives.

Conceptually deriving legitimacy from the Diet, whom it is responsible to, the Cabinet exercises its power in two different ways. In practice, much of its power is exercised by the Prime Minister, while others are exercised nominally by the Emperor.[3]

Article 73 of the Constitution of Japan expects the Cabinet to perform the following functions, in addition to general administration:

- Administer the law faithfully; conduct affairs of state.

- Manage foreign affairs.

- Conclude treaties. However, it shall obtain prior or, depending on circumstances, subsequent approval of the Diet.

- Administer the civil service, in accordance with standards established by law.

- Prepare the budget, and present it to the Diet.

- Enact cabinet orders in order to execute the provisions of this Constitution and of the law. However, it cannot include penal provisions in such cabinet orders unless authorized by such law.

- Decide on general amnesty, special amnesty, commutation of punishment, reprieve, and restoration of rights.

Under the Constitution, all laws and cabinet orders must be signed by the competent Minister and countersigned by the Prime Minister, before being formally promulgated by the Emperor. Also, all members of the Cabinet cannot be subject to legal action without the consent of the Prime Minister; however, without impairing the right to take legal action.[47]

| Office | Incumbent |

|---|---|

| Prime Minister | Shinzō Abe |

| Deputy Prime Minister Minister of Finance Minister of State for Financial Services Minister of State for Overcoming Deflation |

Tarō Asō |

| Minister of Internal Affairs and Communications Minister of State for the Social Security and Tax Number System |

Masatoshi Ishida |

| Minister of Justice | Takashi Yamashita |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | Tarō Kōno |

| Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Minister of State for Education Rebuilding |

Masahiko Shibayama |

| Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare Minister for Working-style Reform |

Takumi Nemoto |

| Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries | Takamori Yoshikawa |

| Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry Minister of State for Industrial Competitiveness Minister of State for Economic Cooperation with Russia Minister of State for the Response to the Economic Impact Caused by the Nuclear Accident at Fukushima Minister of State for the Nuclear Damage Compensation and Decommissioning Facilitation Corporation |

Hiroshige Sekō |

| Minister of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism Minister of State for Water Cycle Policy |

Keiichi Ishii |

| Minister of the Environment Minister of State for Nuclear Emergency Preparedness |

Yoshiaki Harada |

| Minister of Defense | Takeshi Iwaya |

| Chief Cabinet Secretary Minister of State for Mitigating the Impact of U.S. Forces in Okinawa |

Yoshihide Suga |

| Minister for Reconstruction Minister of State for Comprehensive Policy Coordination for Revival from the Nuclear Accident at Fukushima |

Hiromichi Watanabe |

| Chairperson of the National Public Safety Commission Minister of State for Building National Resilience Minister of State for Disaster Management |

Junzo Yamamoto |

| Minister for Promoting Dynamic Engagement of All Citizens Minister of State for Administrative Reform Minister of State for Civil Service Reform Minister of State for Territorial Issues Minister of State for Okinawa and Northern Territories Affairs Minister of State for Consumer Affairs and Food Safety Minister of State for Measures for the Declining Birthrate Minister of State for Ocean Policy |

Mitsuhiro Miyakoshi |

| Minister of State for Information Technology Policy Minister of State for the Cool Japan Strategy Minister of State for Intellectual Property Strategy Minister of State for Science and Technology Policy Minister of State for Space Policy |

Takuya Hirai |

| Minister of State for Economic and Fiscal Policy Minister of State for Social Security Reform Minister of State for TPP and Japan-U.S. Trade Negotiations |

Toshimitsu Motegi |

| Minister of State for Regional Revitalization Minister of State for Regulatory Reform Minister of State for Gender Equality Minister of State for Women's Empowerment |

Satsuki Katayama |

| Minister of State for the Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic Games | Yoshitaka Sakurada |

Ministries

The Ministries of Japan (行政機関) consist of eleven ministries and the Cabinet Office. Each ministry is headed by a Minister of State, which are mainly senior legislators, and are appointed from among the members of the Cabinet by the Prime Minister. The Cabinet Office, formally headed by the Prime Minister, is an agency that handles the day-to-day affairs of the Cabinet. The ministries are the most influential part of the daily-exercised executive power, and since few ministers serve for more than a year or so necessary to grab hold of the organisation, most of its power lies within the senior bureaucrats.[50]

- ※Manages the Imperial Household.

- Reconstruction Agency

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications

- Environmental Dispute Coordination Commission

- Fire and Disaster Management Agency

- Ministry of Justice

- Public Security Examination Commission

- Public Security Intelligence Agency

- Public Prosecutors Office

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs

- Ministry of Finance

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT)

- Agency for Cultural Affairs

- ※Promotes Arts and Culture, manages copyrights, as well as funding for cultural events in music, theater, dance, art exhibitions, and film-making, and making improvements to the national language.

- Sports Agency

- Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare

- Pension Service

- Central Labour Relations Commission

- Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries

- Fisheries Agency

- Forestry Agency

- Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI)

- Agency for Natural Resources and Energy

- Small and Medium Enterprise Agency

- Patent Office

- ※Administers the laws relating to patents, utility models, designs, and trademarks.

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT)

- Ministry of the Environment

- Ministry of Defense

- Acquisition, Technology and Logistics Agency

- Self-Defense Forces (Ground / Maritime / Air)

※ As of October 14, 2018[51][52]

The Board of Audit (会計検査院) is the only unique body of the Government; in which, the Board is totally independent from the Diet and the Cabinet. It reviews government expenditures and submits an annual report to the Diet. Article 90 of the Constitution of Japan and the Board of Audit Act of 1947 gives this body substantial independence from both controls.[53]

Legislative

The Legislative branch organ of Japan is the National Diet (国会). It is a bicameral legislature, composing of a lower house, the House of Representatives, and an upper house, the House of Councillors. Empowered by the Constitution to be "the highest organ of State power" and the only "sole law-making organ of the State", its houses are both directly elected under a parallel voting system and is ensured by the Constitution to have no discrimination on the qualifications of each members; whether be it based on "race, creed, sex, social status, family origin, education, property or income". The National Diet, therefore, reflects the sovereignty of the people; a principle of popular sovereignty whereby the supreme power lies within, in this case, the Japanese people.[7][54]

The Diet responsibilities includes the making of laws, the approval of the annual national budget, the approval of the conclusion of treaties and the selection of the Prime Minister. In addition, it has the power to initiate draft constitutional amendments, which, if approved, are to be presented to the people for ratification in a referendum before being promulgated by the Emperor, in the name of the people.[55] The Constitution also enables both houses to conduct investigations in relation to government, demand the presence and testimony of witnesses, and the production of records, as well as allowing either house of the Diet to demand the presence of the Prime Minister or the other Minister of State, in order to give answers or explanations whenever so required.[40] The Diet is also able to impeach Court judges convicted of criminal or irregular conduct. The Constitution, however, does not specify the voting methods, the number of members of each house, and all other matters pertaining to the method of election of the each members, and are thus, allowed to be determined for by law.[56]

Under the provisions of the Constitution and by law, all adults aged over 18 are eligible to vote, with a secret ballot and a universal suffrage, and those elected have certain protections from apprehension while the Diet is in session.[57] Speeches, debates, and votes cast in the Diet also enjoy parliamentary privileges. Each house is responsible for disciplining its own members, and all deliberations are public unless two-thirds or more of those members present passes a resolution agreeing it otherwise. The Diet also requires the presence of at least one-third of the membership of either house in order to constitute a quorum.[58] All decisions are decided by a majority of those present, unless otherwise stated by the Constitution, and in the case of a tie, the presiding officer has the right to decide the issue. A member cannot be expelled, however, unless a majority of two-thirds or more of those members present passes a resolution therefor.[59]

Under the Constitution, at least one session of the Diet must be convened each year. The Cabinet can also, at will, convoke extraordinary sessions of the Diet and is required to, when a quarter or more of the total members of either house demands it.[60] During an election, only the House of Representatives is dissolved. The House of Councillors is however, not dissolved but only closed, and may, in times of national emergency, be convoked for an emergency session.[61] The Emperor both convokes the Diet and dissolves the House of Representatives, but only does so on the advice of the Cabinet.

For bills to become Law, they are to be first passed by both houses of the National Diet, signed by the Ministers of State, countersigned by the Prime Minister, and then finally promulgated by the Emperor; however, without specifically giving the Emperor the power to oppose legislation.

House of Representatives

The House of Representatives of Japan (衆議院) is the Lower house, with the members of the house being elected once every four years, or when dissolved, for a four-year term.[62] As of November 18, 2017, it has 465 members. Of these, 176 members are elected from 11 multi-member constituencies by a party-list system of proportional representation, and 289 are elected from single-member constituencies. 233 seats are required for majority. The House of Representatives is the more powerful house out of the two, it is able to override vetoes on bills imposed by the House of Councillors with a two-thirds majority. It can, however, be dissolved by the Prime Minister at will.[38] Members of the house must be of Japanese nationality; those aged 18 years and older may vote, while those aged 25 years and older may run for office in the lower house.[57]

The legislative powers of the House of Representatives is considered to be more powerful than that of the House of Councillors. While the House of Councillors has the ability to veto most decisions made by the House of Representatives, some however, can only be delayed. This includes the legislation of treaties, the budget, and the selection of the Prime Minister. The Prime Minister, and collectively his Cabinet, can in turn, however, dissolve the House of Representatives whenever intended.[38] While the House of Representatives is considered to be officially dissolved upon the preparation of the document, the House is only formally dissolved by the dissolution ceremony.[63] The dissolution ceremony of the House is as follows:

- The document is rubber stamped by the Emperor, and wrapped in a purple silk cloth; an indication of a document of state act, done on behalf of the people.

- The document is passed on to the Chief Cabinet Secretary at the House of Representatives President's reception room.

- The document is taken to the Chamber for preparation by the General-Secretary.

- The General-Secretary prepares the document for reading by the Speaker.

- The Speaker of the House of Representatives promptly declares the dissolution of the House.

- The House of Representatives is formally dissolved.

It is customary that, upon the dissolution of the House, members will shout the Three Cheers of Banzai (萬歲).[63][64]

House of Councillors

The House of Councillors of Japan (参議院) is the Upper house, with half the members of the house being elected once every three years, for a six-year term. As of November 18, 2017, it has 242 members. Of these, 73 are elected from the 47 prefectural districts, by single non-transferable votes, and 48 are elected from a nationwide list by proportional representation with open lists. The House of Councillors cannot be dissolved by the Prime Minister.[61] Members of the house must be of Japanese nationality; those aged 18 years and older may vote, while those aged 30 years and older may run for office in the upper house.[57]

As the House of Councillors can veto a decision made by the House of Representatives, the House of Councillors can cause the House of Representatives to reconsider its decision. The House of Representatives however, can still insist on its decision by overwriting the veto by the House of Councillors with a two-thirds majority of its members present. Each year, and when required, the National Diet is convoked at the House of Councillors, on the advice of the Cabinet, for an extra or an ordinary session, by the Emperor. A short speech is, however, usually first made by the Speaker of the House of Representatives before the Emperor proceeds to convoke the Diet with his Speech from the throne.[65]

Judicial

The Judicial branch of Japan consists of the Supreme Court, and four other lower courts; the High Courts, District Courts, Family Courts and Summary Courts.[66] Divided into four basic tiers, the Court's independence from the executive and legislative branches are guaranteed by the Constitution, and is stated as: "no extraordinary tribunal shall be established, nor shall any organ or agency of the Executive be given final judicial power"; a feature known as the Separation of Powers.[8] Article 76 of the Constitution states that all the Court judges are independent in the exercise of their own conscience and that they are only bounded by the Constitution and the laws.[67] Court judges are removable only by public impeachment, and can only be removed, without impeachment, when they are judicially declared mentally or physically incompetent to perform their duties.[68] The Constitution also explicitly denies any power for executive organs or agencies to administer disciplinary actions against judges.[68] However, a Supreme Court judge may be dismissed by a majority in a referendum; of which, must occur during the first general election of the National Diet's House of Representatives following the judge's appointment, and also the first general election for every ten years lapse thereafter.[69] Trials must be conducted, with judgment declared, publicly, unless the Court "unanimously determines publicity to be dangerous to public order or morals"; with the exception for trials of political offenses, offenses involving the press, and cases wherein the rights of people as guaranteed by the Constitution, which cannot be deemed and conducted privately.[70] Court judges are appointed by the Cabinet, in attestation of the Emperor, while the Chief Justice is appointed by the Emperor, after being nominated by the Cabinet; which in practice, known to be under the recommendation of the former Chief Justice.[71]

The Legal system in Japan has been historically influenced by Chinese law; developing independently during the Edo period through texts such as Kujikata Osadamegaki.[72] It has, however, changed during the Meiji Restoration, and is now largely based on the European civil law; notably, the civil code based on the German model still remains in effect.[73] A quasi-jury system has recently came into use, and the legal system also includes a bill of rights since May 3, 1947.[74] The collection of Six Codes makes up the main body of the Japanese statutory law.[73]

All Statutory Laws in Japan are required to be rubber stamped by the Emperor with the Privy Seal of Japan (天皇御璽), and no Law can take effect without the Cabinet's signature, the Prime Minister's countersignature and the Emperor's promulgation.[75][76][77][78][79]

Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of Japan (最高裁判所) is the court of last resort and has the power of Judicial review; as defined by the Constitution to be "the court of last resort with power to determine the constitutionality of any law, order, regulation or official act".[80] The Supreme Court is also responsible for nominating judges to lower courts and determining judicial procedures. It also oversees the judicial system, overseeing activities of public prosecutors, and disciplining judges and other judicial personnel.[81]

High Courts

The High Courts of Japan (高等裁判所) has the jurisdiction to hear appeals to judgments rendered by District Courts and Family Courts, excluding cases under the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court. Criminal appeals are directly handled by the High Courts, but Civil cases are first handled by District Courts. There are eight High Courts in Japan: the Tokyo, Osaka, Nagoya, Hiroshima, Fukuoka, Sendai, Sapporo, and Takamatsu High Courts.[81]

Penal system

The Penal system of Japan (矯正施設) is operated by the Ministry of Justice. It is part of the criminal justice system, and is intended to resocialize, reform, and rehabilitate offenders. The ministry's Correctional Bureau administers the adult prison system, the juvenile correctional system, and three of the women's guidance homes,[82] while the Rehabilitation Bureau operates the probation and the parole systems.[83]

Local government

| Administrative divisions of Japan |

|---|

| Prefectural |

| Prefectures |

| Sub-prefectural |

| Municipal |

| Sub-municipal |

The local governments of Japan (地方公共団体) are municipal corporations. Their body and functions are defined by law; more specifically, the Local Autonomy Law.[84][85] They are given limited executive and legislative powers by the Constitution. Governors, mayors and members of assemblies are constitutionally elected by the residents.

The Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications intervenes significantly in local government, as do other ministries. This is done chiefly financially because many local government jobs need funding initiated by national ministries. This is dubbed as the "thirty-percent autonomy".[86]

The result of this power is a high level of organizational and policy standardization among the different local jurisdictions allowing them to preserve the uniqueness of their prefecture, city, or town. Some of the more collectivist jurisdictions, such as Tokyo and Kyoto, have experimented with policies in such areas as social welfare that later were adopted by the national government.[86]

Local authorities

Japan is divided into forty-seven administrative divisions, the prefectures are: one metropolitan district (Tokyo), two urban prefectures (Kyoto and Osaka), forty-three rural prefectures, and one "district", Hokkaidō. Large cities are subdivided into wards, and further split into towns, or precincts, or subprefectures and counties.

Cities are self-governing units administered independently of the larger jurisdictions within which they are located. In order to attain city status, a jurisdiction must have at least 500,000 inhabitants, 60 percent of whom are engaged in urban occupations. There are self-governing towns outside the cities as well as precincts of urban wards. Like the cities, each has its own elected mayor and assembly. Villages are the smallest self-governing entities in rural areas. They often consist of a number of rural hamlets containing several thousand people connected to one another through the formally imposed framework of village administration. Villages have mayors and councils elected to four-year terms.[87][88]

Structure

Each jurisdiction has a chief executive, called a governor (知事, chiji) in prefectures and a mayor (市町村長, shichōsonchō) in municipalities. Most jurisdictions also have a unicameral assembly (議会, gikai), although towns and villages may opt for direct governance by citizens in a general assembly (総会, sōkai). Both the executive and assembly are elected by popular vote every four years.[89][90][91]

Local governments follow a modified version of the separation of powers used in the national government. An assembly may pass a vote of no confidence in the executive, in which case the executive must either dissolve the assembly within ten days or automatically lose their office. Following the next election, however, the executive remains in office unless the new assembly again passes a no confidence resolution.[85]

The primary methods of local lawmaking are local ordinance (条例, jōrei) and local regulations (規則, kisoku). Ordinances, similar to statutes in the national system, are passed by the assembly and may impose limited criminal penalties for violations (up to 2 years in prison and/or 1 million yen in fines). Regulations, similar to cabinet orders in the national system, are passed by the executive unilaterally, are superseded by any conflicting ordinances, and may only impose a fine of up to 50,000 yen.[87]

Local governments also generally have multiple committees such as school boards, public safety committees (responsible for overseeing the police), personnel committees, election committees and auditing committees.[92] These may be directly elected or chosen by the assembly, executive or both.[86]

All prefectures are required to maintain departments of general affairs, finance, welfare, health, and labor. Departments of agriculture, fisheries, forestry, commerce, and industry are optional, depending on local needs. The Governor is responsible for all activities supported through local taxation or the national government.[86][90]

See also

- Politics of Japan

- Japanese honors system

References

- "The World Factbook Japan". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- Article 4(1), Section 1 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- Article 65, Section 5 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- Article 68(1), Section 5 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- Article 67(1), Section 5 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- Article 6(1), Section 1 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- Article 1, Section 1 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- Article 76(2), Section 6 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- Chaurasla, Radhey Shyam (2003). History of money. New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers and Distributors. p. 10. ISBN 9788126902286.

- Koichi, Mori (December 1979). "The Emperor of Japan: A Historical Study in Religious Symbolism". Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. 6/4: 535–540.

- Bob Tadashi, Wakabayashi (1991). "In Name Only: Imperial Sovereignty in Early Modern Japan". Journal of Japanese Studies. 7 (1): 25–57.

- Satow, Ernest Mason (Aug 23, 2013). A Diplomat in Japan. Project Gutenberg. p. 282. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- "Asia's First Parliament" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- "The Nature of Sovereignty in Japan, 1870s–1920s" (PDF). University of Colorado Boulder. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- Lebra, Takie Sugiyama (1992). Japanese social organization (1 ed.). Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 51. ISBN 9780824814205.

- Article 34, Section 3 of the Constitution of the Empire of Japan (1889)

- Article 35, Section 3 of the Constitution of the Empire of Japan (1889)

- Skya, Walter A. (2009). Japan's holy war the ideology of radical Shintō ultranationalism. Durham: Duke University Press. p. 40. ISBN 9780822392460.

- Martin, Bernd (2006). Japan and Germany in the modern world (1. paperback ed.). New York [u.a.]: Berghahn Books. p. 31. ISBN 9781845450472.

- "The Constitution: Context and History" (PDF). Hart Publishing. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- "Japan's analog government struggles to accept anything online". Nikkei. Archived from the original on 18 June 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Article 4, Section 1 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- "Did the Emperor of Japan really fall from being a ruler to a symbol" (PDF). Tsuneyasu Takeda. Instructor, Keio University. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- "2009 Japanese Emperor and Empress Visited in Vancouver". Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- "A shadow of a shogun". The Economist. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- "Fundamental Structure of the Government of Japan". Prime Minister's Official Residence Website. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- Article 5, Section 1 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- "最高裁判所判例集 事件番号 平成1(行ツ)126". Courts in Japan. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

- "Japan's royal family pose for unusual New Year photo". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- Kitagawa, Joseph M. (1987). On understanding Japanese religion. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. p. 145. ISBN 9780691102290.

- Smith, Robert J. (1974). Ancestor worship in contemporary Japan ([Repr.]. ed.). Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. pp. 8–9. ISBN 9780804708739.

- "Kojiki". Ō no Yasumaro. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- "Nihon Shoki" (PDF). Prince Toneri. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- "Enthronement and Ceremonies". Imperial Household Agency. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- "The 20th Anniversary of His Majesty the Emperor's Accession to the Throne". Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- Article 69, Section 5 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- Article 72, Section 5 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- Article 7, Section 1 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- Article 67(2), Section 5 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- Article 63, Section 4 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- Article 66(2), Section 5 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-08-14. Retrieved 2016-10-10.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "内閣法". Government of Japan. Archived from the original on 25 April 2010. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- "Toshiaki Endo appointed Olympics minister". The Japan Times. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- Article 68, Section 5 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- Article 68(2), Section 5 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- Article 75 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- "第3次安倍内閣 閣僚等名簿". Prime Minister's Official Residence Website. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- "CABINET PROFILES". The Japan Times. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- "Bureaucrats of Japan". Library of Congress Country Studies. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- "Links to Ministries and Other Organizations". Prime Minister's Official Residence Website. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- "Ministries and Agencies". Government of Japan Website. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- "Board of Audit of Japan". Board of Audit. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- Article 43(1), Section 4 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- Article 96, Section 9 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- Article 64(1), Section 4 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- "Diet enacts law lowering voting age to 18 from 20". The Japan Times. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- Article 56(1), Section 4 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- Article 55, Section 4 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- Article 53, Section 4 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- Article 54(2), Section 4 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- Article 45, Section 4 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- "解散と万歳". Democratic Party of Japan. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- "小泉進次郎氏、衆議院解散でも万歳しなかった「なぜ今、解散か」". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- "開会式". House of Councillors. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- "Overview of the Judicial System in Japan". Supreme Court of Japan. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- Article 76, Section 6 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- Article 78, Section 6 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- Article 79(2), Section 6 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- Article 82(2), Section 6 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- "Change at the top court's helm". The Japan Times. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- Dean, Meryll (2002). Japanese legal system : text, cases & materials (2nd ed.). London: Cavendish. pp. 55–58. ISBN 9781859416730.

- "Japanese Civil Code". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- "MacArthur and the American Occupation of Japan". Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- Article 74, Section 5 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- Article 7(1), Section 1 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- "II. The law-making process". Cabinet Legislation Bureau. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- "The Privy Seal and State Seal". Imperial Household Agency. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- "Promulgation of Laws". National Printing Bureau. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- Article 81, Section 6 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- "Overview of the Judicial System in Japan". Supreme Court of Japan. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- "Correction Bureau". Ministry of Justice. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- "Rehabilitation Bureau". Ministry of Justice. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- Article 92, 93, 94 and 95, Section 8 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- "AUTHORITY OF THE NATIONAL AND LOCAL GOVERNMENTS UNDER THE CONSTITUTION". Duke University School of Law. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- 三割自治 "Local Government". Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- "Local Autonomy Law". Government of Japan. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- "The Large City System of Japan" (PDF). National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- Article 93(2), Section 8 of the Constitution of Japan (1947)

- "Local Autonomy in Japan Current Situation & Future Shape" (PDF). Council of Local Authorities for International Relations. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- "An Outline of Local Government in Japan" (PDF). Council of Local Authorities for International Relations. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- "The Organization of Local Government Administration in Japan" (PDF). National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

External links

- Background notes of the US Department of State, Japan's Government

- Search official Japanese Government documents and records

- Facts about Japan by CIA's The World Factbook

- Video of the Enthronement Ceremony of the Emperor

- Video of the National Diet Convocation Ceremony

- Video of the House of Representatives Dissolution Ceremony

- Works by Government of Japan at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)