Transport in Japan

Transportation in Japan is modern and highly developed. Japan's transport sector stands out for its energy efficiency: it uses less energy per person compared to other countries, thanks to a high share of rail transport and low overall travel distances.[1] Transport in Japan is also very expensive in international comparison, reflecting high tolls and taxes, particularly on automobile transport.[2]

Japan's spending on roads has been large.[3] The 1.2 million kilometres of paved road are the main means of transport.[4] Japan has left-hand traffic. A single network of high-speed, divided, limited-access toll roads connects major cities, which are operated by toll-collecting enterprises.

Dozens of Japanese railway companies compete in regional and local passenger transport markets; for instance, seven JR Group companies, Kintetsu Railway, Seibu Railway, and Keio Corporation. Often, strategies of these enterprises contain real estate or department stores next to stations. Some 250 high-speed Shinkansen trains connect major cities. All trains are known for punctuality.

There are 176 airports,[5] and the largest domestic airport, Haneda Airport, is Asia's busiest airport. The largest international gateways are Narita International Airport (Tokyo area), Kansai International Airport (Osaka/Kobe/Kyoto area), and Chūbu Centrair International Airport (Nagoya area). The largest ports include Nagoya Port.

Railway

In Japan, railways are a major means of passenger transport, especially for mass and high-speed transport between major cities and for commuter transport in metropolitan areas. Seven Japan Railways Group companies, state-owned until 1987, cover most parts of Japan. There also are railway services operated by private rail companies, regional governments, and companies funded by both regional governments and private companies.

Total railways of 27,182 km include several track gauges, the most common of which is 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) narrow gauge, with 22,301 km of track of which 15,222 km is electrified.[6]

Fukuoka, Kobe, Kyoto, Nagoya, Osaka, Sapporo, Sendai, Tokyo, and Yokohama have subway systems.

Most Japanese people travelled on foot until the later part of the 19th century. The first railway was built between Tokyo's Shimbashi Station and Yokohama's former Yokohama Station (now Sakuragichō Station) in 1872.[7] Many more railways developed soon afterward. Japan, as we know it today, is home to one of the world's most developed transport networks. Mass transport is well developed in Japan, but the road system lags behind and is inadequate for the number of cars owned in Japan. This is often attributed to the fact that road construction is difficult in Japan because of its uniquely high population density, and the limited amount of available usable land for road construction.

Shinkansen (bullet train)

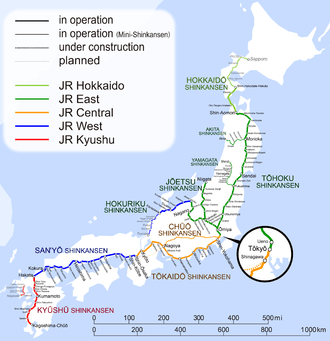

The Shinkansen, or "bullet trains", as they are often known, are the high-speed rail trains that run across Japan.[8] The 2,387 km (1,485 mi) of 8 Shinkansen lines run on completely separate lines from their commuting train counterparts, with a few exceptions. Shinkansen take up a large portion of the long distance travel in Japan, with the whole system carrying over 10 billion passengers in its lifetime. 1,114,000 journeys are made daily, with the fastest train being the JR East E5 and E6 series trains, which operate at a maximum speed of 320 km/h (200 mph). Shinkansen trains are known to be very safe, with no accident-related deaths or injuries from passengers in its 50-plus year history.[9] Shinkansen trains are also known to be very punctual, following suit with all other Japanese transport; in 2003, the average delay per train on the Tokaido Shinkansen was a mere 6 seconds.[10] Japan has been trying to sell its Shinkansen technology overseas, and has struck deals to help build systems in India, Thailand, and the United States.[9]

The first Shinkansen line opened between Tokyo and Osaka in 1964, and trains can now make the journey in 2 hours and 25 minutes.[8] Additional Shinkansen lines connect Tokyo to Aomori, Niigata, Kanazawa, and Hakodate and Osaka to Fukuoka and Kagoshima, with new lines under construction to Tsuruga, Sapporo and Nagasaki.

Japan has been developing maglev technology trains, and broke the world maglev speed record in April 2015 with a train travelling at the speed of 603 km/h (375 mph).[11] The Chūō Shinkansen, a commercial maglev service, is currently under construction from Tokyo to Nagoya and Osaka, and when completed in 2045 will cover the distance in 67 minutes, half the time of the current Shinkansen.

Road

According to Japan Statistical Yearbook 2015, Japan in April 2012 had approximately 1,215,000 km of roads made up of 1,022,000 km of city, town and village roads, 129,000 km of prefectural roads, 55,000 km of general national highways and 8,050 km of national expressways.[12][13] The Foreign Press Center/Japan cites a total length of expressways at 7,641 km (fiscal 2008).[14] A single network of high-speed, divided, limited-access toll roads connects major cities on Honshu, Shikoku and Kyushu. Hokkaido has a separate network, and Okinawa Island has a highway of this type. In the year 2005, the toll collecting companies, formerly Japan Highway Public Corporation, have been transformed into private companies in public ownership, and there are plans to sell parts of them. The aim of this policy is to encourage competition and decrease tolls.

Road passenger and freight transport expanded considerably during the 1980s as private ownership of motor vehicles greatly increased along with the quality and extent of the nation's roads. Bus companies including the JR Bus companies operate long-distance bus services on the nation's expanding expressway network. In addition to relatively low fares and deluxe seating, the buses are well utilised because they continue service during the night, when air and train services are limited.

The cargo sector grew rapidly in the 1980s, recording 274.2 billion tonne-kilometres in 1990. The freight handled by motor vehicles, mainly trucks, in 1990, was over 6 billion tonnes, accounting for 90 percent of domestic freight tonnage and about 50 percent of tonne-kilometres.

Recent large infrastructure projects were the construction of the Great Seto Bridge and the Tokyo Bay Aqua-Line (opened 1997).

Road safety

Road fatalities decrease in Japan, due in part to stricter enforcement of drunk driving laws:

- 2004 still saw 7,358 deaths on Japanese roads,

- 2017 has 3,694 deaths for 125 million population,[15]

- 2019 see 3,215 deaths, best since 1948, with a rate of 25.4 deaths per million[16] better than many European nations, and near of the UK rate.

In Tokyo, road safety is 13 killed per million.[17]

Airway

In 2013 Japan had the fourth largest passenger air market in the world with 105,913,000 passengers.[18] In 2013 Japan had 98 airports.[19] The main international gateways are Narita International Airport (Tokyo area), Kansai International Airport (Osaka/Kobe/Kyoto area), and Chūbu Centrair International Airport (Nagoya area). The main domestic hub is Tokyo International Airport (Haneda Airport), Asia's busiest airport and the world's 4th busiest airport; other major traffic hubs include Osaka International Airport, New Chitose Airport outside Sapporo, and Fukuoka Airport. 14 heliports are estimated to exist (1999).

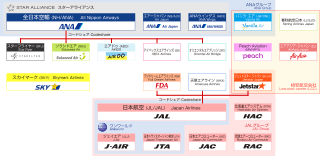

The two main airlines are Japan Airlines and All Nippon Airways. Other passenger carriers include Skymark Airlines, Skynet Asia Airways, Air Do, Star Flyer and Fuji Dream Airlines. United Airlines and Delta Air Lines, formerly Northwest Airlines, are major international operators from Narita Airport.

Domestic air travel in Japan has historically been highly regulated. From 1972, the three major domestic airlines (JAL, ANA, and JAS) were allocated certain routes, with JAL and ANA sharing trunk routes, and ANA and JAS sharing local feeder routes. JAL and JAS have since been merged to help compete with ANA. JAL also had a flag-carrier monopoly on international routes until 1986. Airfares were set by the government until 2000, although carriers had freedom to adjust the standard fares starting in 1995 (when discounts of up to 50% were permitted). Today, fares can be set by carriers, but the government retains the ability to veto fares that are too high.

Maritime

There are 1770 km of waterways in Japan; seagoing craft ply all coastal inland seas.[20]

There are some 994 ports in Japan as of April 2014.[21] There are overlapping classifications of these ports, some of which are multi-purpose, e.g. cargo, passenger, naval, and fishery. The five designated "super" container ports are: Yokkaichi, Yokohama, Nagoya, Kobe and Osaka. 23 are designated major/international, 125 designated as important, while there are also purely fisherman ports.

The twenty-three major seaports designated as special, important ports by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism : Chiba, Fushiki/Toyama, Himeji, Hiroshima, Kawasaki, Kitakyūshū, Kobe, Kudamatsu, Muroran, Nagoya, Niigata, Osaka, Sakai/Senpoku, Sendai/Shiogama, Shimizu, Shimonoseki, Tokyo, Tomakomai, Wakayama, Yokkaichi, and Yokohama.

Japan has 988 ships of 1,000 gross tonnage (GT) or over on its national ship register, totaling 38,053,000 tonnes deadweight (DWT). However, only 17% of Japanese-owned capacity is registered in Japan. UNCTAD estimates that 224 million dwt of tonnage is controlled by Japanese owners, making Japan the second largest beneficial owner of tonnage after Greece.[22]

Ferries connect Hokkaido to Honshu, and Okinawa Island to Kyushu and Honshu. They also connect other smaller islands and the main islands. The scheduled international passenger routes are to China, Russia, South Korea and Taiwan. Coastal and cross-channel ferries on the main islands decreased in routes and frequencies following the development of bridges and expressways but some are still operating (as of 2007).

Pipelines

Japan has 84 km of pipelines for crude oil, 322 km for petroleum products, and 1,800 km for natural gas.

By region

- Transport in Greater Tokyo

- Transport in Greater Osaka

- Transport in Greater Nagoya

- Transport in Fukuoka-Kitakyushu

References

- Lipscy Phillip Y., Schipper Lee (2013). "Energy efficiency in the Japanese transport secto". Energy Policy. 56: 248–258. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2012.12.045.

- Lipscy Phillip Y (2012). "A Casualty of Political Transformation? The Politics of Japanese Energy Efficiency in the Transportation Sector" (PDF). Journal of East Asian Studies. 12: 3. doi:10.1017/S1598240800008080.

- Japan's Road to Deep Deficit Is Paved With Public Works, New York Times in 1997

- Chapter 9 Transport Archived 27 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Statistical Handbook of Japan

- The CIA World Factbook

- "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov.

- "Ever-evolving Yokohama Station marks 100th year". The Japan Times. Kyodo News. 14 August 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- Ryall, Julian (1 October 2014). "Bullet train at 50: rise and fall of the world's fastest train". The Telegraph. Tokyo. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- Lufkin, Bryan (28 December 2015). "How Japan's Bullet Train Is Taking Over the World". Gizmodo. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- The Japan Times: "Tokaido Shinkansen Line fetes 40 years" (2 October 2004). Retrieved on 27 April 2009.

- McCurry, Justin (21 April 2015). "Japan's maglev train breaks world speed record with 600km/h test run". The Guardian. Tokyo. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- Chapter 12 Transport - Microsoft Excel Sheet, Statistical Handbook of Japan

- "Road Bureau - MLIT Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism". www.mlit.go.jp.

- Facts and Figures of Japan, 14: Transport Archived 6 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Foreign Press Center/Japan

- https://www.japanallover.com/2019/01/traffic-accidents-road-safety-japan/

- https://www.nippon.com/en/japan-data/h00368/annual-traffic-fatalities-in-japan-reach-record-low.html

- https://www.businessinsider.com/one-of-the-worlds-biggest-cities-has-figured-how-to-virtually-eliminate-traffic-deaths-2015-7?IR=T

- World Bank Database, http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IS.AIR.PSGR

- "Transportation in Japan". www.asianinfo.org. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 January 2015. Retrieved 23 December 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "UNCTAD Review of Maritime Transport". 2018: 30. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

Further reading

- Daito Eisuke (1989). "Railways and scientific management in Japan 1907–30". Business History. 31 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1080/00076798900000001.

- Ericson, Steven J. The Sound of the Whistle: Railroads and the State in Meiji Japan (Harvard Univ Asia Center, 1996).

- Kinzley, W. Dean. "Merging Lines: Organising Japan's National Railroad, 1906-1914" Journal of Transport History 27#2 (2006)

- Peter, Bruce; Ishiyama, Tsuyoshi (2012). Japanese Ferries. Ramsey, Isle of Man: Ferry Publications. ISBN 9781906608620.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Transport in Japan. |

- Hyperdia - Travel planning tool supporting English and Japanese

- Jorudan - Travel planning tool supporting English and Japanese

- Toei Transportation Information - English information on Toei bus, subway, and trolley services and multilingual maps

- Domestic aviation in Japan: Responding to market forces amid regulatory constraints

- Japan Automobile Research Institute (JARI)

- Roads In Japan, from Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT) - English and Japanese website, link refers specifically to 5 PDF chapters - as well as a reference chapter - on road history, statistics, maps, construction and advanced road technologies in Japan (graphics throughout, 41 total pages).

.jpg)