Paiwan people

The Paiwan (Chinese: 排灣; pinyin: Páiwān) are an indigenous people of Taiwan. They speak the Paiwan language. In 2014, the Paiwan numbered 96,334. This was approximately 17.8% of Taiwan's total indigenous population, making them the second-largest indigenous group.[1][2]

Paywan, Kacalisian | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Total population | |

| 100,000 (Dec 2017) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Taiwan | |

| Languages | |

| Mandarin, Paiwan | |

| Religion | |

| Animism, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Malayo-Polynesians, Taiwanese Aborigines |

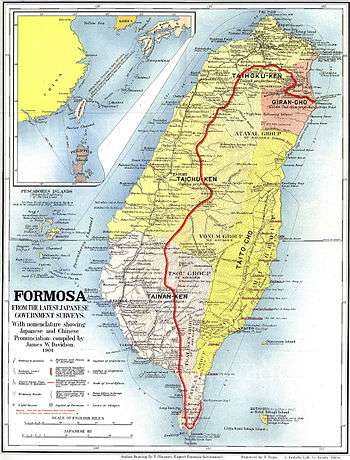

The majority of Paiwan people live in the southern chain of the Central Mountain Range, from Damumu Mountain and the upper Wuluo River in the north of the southern chain to the Hengchun Peninsula in the south of it, and also in the hills and coastal plains of southeastern Taiwan. There are two subgroups under the Paiwan people: the Raval and the Butsul.[3]

The unique ceremonies in Paiwan are Masaru and Maleveq. The Masaru is a ceremony that celebrates the harvest of rice, whereas the Maleveq commemorates their ancestors or gods.

History

The name "Paiwan" may have originated from a myth. According to the myth, Paiwan ancestors lived in a location on Dawu mountain that was called "Paiwan", where heaven is said to exist. Paiwan people have spread out from this location, so the name of the original place was assumed as their group name. According to some group members, "Paiwan" also means "human being".[3]

One of the most important figures in Paiwan history was supreme chief Tok-a-Tok[4] (c. 1817–1874),[lower-alpha 1][5] who united 18 tribes of Paiwan under his rule, and after defeating American Marines during the Formosa Expedition in 1867 he concluded a formal agreement with Chinese and Western leaders to ensure the safety of foreign ships landing on their coastal territories in return for amnesty for Paiwan tribesmen who had killed the crew of the barque Rover in March 1867 (see Rover incident).[6]

In the past, the Paiwan had a fearsome reputation as head-hunters. When Paiwan warriors returned home from a headhunting foray, "the women would gather together in front of the courtyard to welcome their heroes and would sing songs of triumph. The heads of their enemies were then hung on stone pillars in front of which were displayed wine and offerings. The sacrificial rite started, and the soul of the dead was duly consoled by the sorcerer. A tuft of hair was removed from the skull and solemnly put in a basket which was used for divination."

In 1871, a Ryūkyūan vessel shipwrecked on the southern tip of Taiwan, and 54 of the 66 survivors were beheaded by the Paiwan aborigines (Mudan Incident). When Japan sought compensation from Qing China, the court rejected the demand on the grounds that Taiwan's "raw" or "wild" natives (Chinese: 臺灣生番; pinyin: Táiwān shēngfān) were outside its jurisdiction. This perceived renunciation of sovereignty led to the Japanese invasion of Taiwan in 1874 in which chief Tok-a-Tok was killed in action.

During the Chinese Civil War, between 1946 and 1949, many Paiwan men were forcibly enlisted in the Kuomintang forces. When the war ended, some of the Paiwan remained behind in China and formed their own communities.

Tsai Ing-wen, elected as President of Taiwan in 2016, is 1/4 Paiwan via her grandmother.

Customs

Unlike other peoples in Taiwan, Paiwan society is divided into classes with a hereditary aristocracy. The Paiwan are not allowed to marry outside their group. On the day of their "five-yearly rite," all marriage-seeking Paiwan men try to cut down as many trees as possible and offer the firewood thus procured to the family of the girl they want to marry.

Tattooed hands are a tradition of both Paiwan and Rukai peoples. Noble women used to receive these tattoos as a rite of passage into adulthood. However, since the Japanese colonial era, the practice has been less common as it was discouraged and fined during that time. In the tradition, shamans would tattoo hands in different patterns for different personal backgrounds. Less noble women could have received it, but they had to pay a hefty price on top of inviting all members of the community to a banquet with the purpose of gaining the community's approval. Less noble women had different tattoo designs than noblewomen. The painful tattooing process represented dignity and honor and the suffering that one could endure. The tattooing process lasts as long as it needs to with consideration for many taboos and nuances, such as praying. For example, pregnant women were not allowed to watch the process and no one watching was allowed to sneeze. If any taboos were broken, the ritual would be put off until another day chosen.[7]

In February 2015, Li Lin, the oldest Paiwan with hand tattoos, died at the age of 102. Li Lin had her hand tattoos starting at the age of 14 before marrying a village head as a common girl. She played a large role in promoting the cultural art form and continues to be an icon of cultural identity even in her death.[8]

Religion

Traditionally the Paiwan have been polytheists. Their wooden carvings included images of human heads, snakes, deer, and geometric designs. In Taiwan, the Bataul branch of the Paiwan peoples holds a major sacrifice – called maleveq – every five years to invite the spirits of their ancestors to come and bless them. Djemuljat is an activity in the Maleveq in which the participants thrust bamboo poles into cane balls symbolizing human heads.[9]

Shamanism

Shamanism has been described as an important part of Paiwan culture. Paiwan shamanism is traditionally seen as being inherited by blood-line. However, a decline in the number of Paiwan shamans has raised concerns that traditional rituals might be lost; and has led to the founding of a shamanism school to pass on the rituals to a new generation.[10]

Christianity

Christianity first came to the Paiwan people in the seventeenth century, when Taiwan was occupied by the Dutch. More than 5,000 tribesmen became Christians after only ten years, but all of them were massacred in 1661 when Koxinga occupied Taiwan. The missionaries were either killed or driven away, and the churches were destroyed.

Thousands of Paiwan people in Taiwan came to Christianity in the late 1940s and 1950s, sometimes whole villages. Today the Presbyterian church in Taiwan claims 14,900 Paiwan members, meeting in 96 congregations. The New Testament has been translated into Paiwan. The Catholic Church is also very active. The number of young people attending though is falling.[11]

Heritage

In May 2015, two Paiwan totem poles were listed as ROC national treasures by the Bureau of Cultural Heritage under the Ministry of Culture. Both of these artifacts were acquired by the National Taiwan University during the Japanese colonial period (1895–1945). They were submitted for national treasure listing earlier in 2015.[12]

The Paiwan language is one of Taiwan's 42 indigenous tongues and dialects, being one of nine that are listed as vulnerable on the UNESCO atlas of endangered languages.[13]

Notable Paiwan people

- Tsai Ing-wen, President of the Republic of China

- Calivat Gadu, Deputy Minister of the Council of Indigenous Peoples

- Chen Shih-chieh, weightlifter

- Uliw Qaljupayare, member of Legislative Yuan

- Lai Chu-en, boxer

- Ahronglong Sakinu, writer

- Ma Chih-hung, luger

Notes

References

- "Amis remains Taiwan's biggest aboriginal tribe at 37.1% of total". Focus Taiwan. February 15, 2015.

- "Table 28:Indigenous population distribution in Taiwan-Fukien Area". Preliminary statistical analysis report of 2000 Population and Housing Census. National Statistics, Republic of China (Taiwan). Archived from the original (RTF) on October 30, 2014. Retrieved August 30, 2006.

- "Paiwan". Digital Museum of Taiwan Indigenous Peoples. Archived from the original on January 4, 2010. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, 9th ed. (1879), "Formosa".

- See also his article on the Chinese Wikipedia.

- Davidson, James W. (2005) [1903]. The Island of Formosa, Past and Present : history, people, resources, and commercial prospects : tea, camphor, sugar, gold, coal, sulphur, economical plants, and other productions. Taipei, Taiwan: Southern Materials Center. ISBN 957-638-124-X. OL 6931635M.

- 陳賢義 (9 Jul 2009). "Paiwan and Rukai tattoo art fading fast". Taipei Times. Translated by Svensson, Perry. p. 15.

- "Paiwan elder with hand tattoo dies at 102". Taiwan Today. February 10, 2015. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- 謝志鴻. 排灣族五年祭的宗教意涵與身體活動. p. 67.

- Collins, Nick (21 Sep 2009). "School of witchcraft opens in Taiwan". Telegraph.co.uk.

- "Aborigines Losing Their Christianity?". September 25, 2007. Retrieved April 11, 2020.

- "Paiwan totem poles listed as ROC national treasures". Taiwan Today. May 25, 2015. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- "Cabinet OKs indigenous language development bill". Taiwan Today. November 27, 2015. Retrieved December 3, 2016.