Elections in Japan

The Japanese political process has three types of elections: general elections to the House of Representatives held every four years (unless the lower house is dissolved earlier), elections to the House of Councillors held every three years to choose half of its members, and local elections held every four years for offices in prefectures and municipalities. Elections are supervised by Election Administration Commissions at each administrative level under the general direction of the Central Election Management Council, an extraordinary organ attached to the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (MIC). The minimum voting age in Japan's non-compulsory electoral system was reduced from twenty to eighteen years in June 2016.[1] Voters must satisfy a three-month residency requirement before being allowed to cast a ballot.

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Japan |

|

|

|

|

For those seeking offices, there are two sets of age requirements: twenty-five years of age for admission to the House of Representatives and most local offices, and thirty years of age for admission to the House of Councillors and the prefectural governorship. Each deposit for candidacy for national election is 3 million yen (about 27 thousand dollars) for a single-seat constituency and 6 million yen (about 54 thousand dollars) for proportional representation.

National elections

Japan's postwar national legislature, the National Diet (国会, Kokkai), has two directly elected chambers, elected on independent electoral cycles:

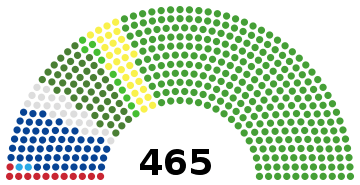

- The House of Representatives (衆議院, Shūgi-in) has 465 members, elected for a rarely completed four-year term, 289 members in single-seat constituencies and 176 members by proportional representation in 11 regional "block" constituencies.

General elections of members of the House of Representatives (衆議院議員総選挙, Shūgi-in giin sō-senkyo) are usually held before the end of a four-year term as the chamber may be dissolved by the cabinet via the Emperor. Most prime ministers use that option. The only exception in post-war history was the "Lockheed election" of 1976 in which the Liberal Democratic Party lost its seat majority for the first time.

The single-seat constituencies are decided by plurality, and the proportional seats are handed out in each "block" constituency to party lists proportionally (by the D'Hondt method) to their share of the vote. Each voter votes twice, once for a candidate in the local constituency, and once for a party in the regional "block" constituency. In a parallel system, there is no link between votes in one tier and seat numbers in the other; but so-called dual candidacies (重複立候補, jūfuku rikkōho) of one candidate in both tiers simultaneously are allowed. If such dual candidates lose in the majoritarian tier, they still have a chance to be elected in the proportional block. Parties may also place dual district and block candidates on the same list rank; in that case, the Sekihairitsu (惜敗率, ratio of margin of defeat) system determines the order of candidates.

- The House of Councillors (参議院, Sangi-in) has 245 members (248 from 2022)[2], elected for a fixed six-year term, 147 (2022–: 148) members by single non-transferable vote (SNTV) in 45 single- and multi-seat constituencies (most are prefectures, two combined constituencies comprise two neighbouring prefectures each) and 98 (2022–: 100) by proportional representation (by D'Hondt method) with optionally open lists in a single, nationwide constituency.

In staggered elections, half of the House of Councillors comes up for election every three years in regular/ordinary elections of members of the House of Councillors (参議院議員通常選挙, Sangi-in giin tsūjō-senkyo). The term is fixed, the House of Councillors cannot be dissolved.

This, too, is a parallel electoral system. Dual candidacies are not allowed. As in House of Representatives elections, voters have two votes: In the majoritarian election, the vote has to be for a candidate, but in the proportional election, the vote may be for either a party list or a single candidate; in the latter case, the vote counts as both a vote for the party list (to determine proportional seat distribution), and as a preference vote within that list (to determine the order or proportional candidates within that list). The district magnitudes in the majoritarian tier vary between one and six, dependent on, but not fully proportional to the population of each prefecture. In single-member constituences, SNTV becomes equivalent to first-past-the-post, whereas seats are usually split between different parties/alliances in multi-member constituencies (and in the proportional constituency by definition). Therefore, the single-member constituencies of the House of Councillors (参議院一人区, Sangiin ichinin-ku) are more likely to swing the election result and often receive more media and campaign attention. The proportional election to the House of Councillors allows the voters to cast a preference vote for a single candidate on a party list. The preference votes strictly determined the ranking of candidates on party lists before 2019. Since the 2019 election, parties are allowed to prioritize individual candidates on their proportional list over voter preferences in a "special frame" (特定枠, tokutei-waku). In the 2019 election, almost all parties continued to use completely open lists; exeptions were the LDP which used the "special frame" to give secure list spots to two LDP prefectural federations affected by the introduction of combined constituencies in 2016, Reiwa Shinsengumi which used it to give secure list spots to two candidates with severe disabilities, and the minor "Labourers' Party for the liberation of labour".[3][4]

The electoral cycles of the two chambers of the Diet are usually not synchronized. Even when the current constitution took effect in 1947, the first House of Councillors election was held several days apart from the 23rd House of Representatives election. Only in 1980 and 1986, general and regular election coincided on the same day because the House of Representatives was dissolved in time for the election to be scheduled together with the House of Councillors election in early summer.

Vacant district seats in both Houses are generally filled in by-elections (補欠選挙, hoketsu senkyo). Nowadays, these are usually scheduled in April and October as necessary. Vacant proportional seats in both Houses and district seats in the House of Councillors that fall vacant within three months of a regular election are filled by kuriage-tōsen (繰り上げ当選, roughly "being elected as runner-up"): the highest ranking candidate on a proportional list or in the electoral district who was not elected and is not disqualified takes the seat. Disqualifications may, for example, happen if a candidate for the House of Councillors runs for the House of Representatives or vice versa, or after a violation of campaign laws.

For many years, Japan was a one party dominant state until 1993 with the Liberal Democratic Party (自由民主党, Jiyū-Minshu-tō) as the ruling party. It won a majority of the popular vote in House of Representatives general elections until the 1960s. It lost the majority of seats in 1976 and 1979, but continued to rule without coalition partners with the support of independent Representatives. After the 1983 election when it again lost the majority, it entered a coalition for the first time – with the New Liberal Club (新自由クラブ, Shin-Jiyū-kurabu). In 1986, the coalition ended as the LDP won a large majority of seats and even came close to a majority of votes. The party suffered its first clear electoral defeat in the 1989 House of Councillors regular election when it lost the upper house majority and had to face for the first time a divided Diet (ねじれ国会, Nejire Kokkai, lit. "twisted Diet") where passing legislation depends on cooperation with the opposition. The LDP was out of government for the first time in 1993 after Ichirō Ozawa and his faction had left the party and the opposition parties united in an anti-LDP coalition, but then soon returned to the majority in 1994 by entering a coalition with its traditional main opponent, the Japan Socialist Party (日本社会党, Nihon-Shakai-tō). The 2009 House of Representatives elections handed the first non-LDP victory to the Democratic Party of Japan (民主党, Minshu-tō).

According to a survey by Yomiuri Shimbun in April 2010, almost half of Japanese voters do not support any political parties due to political inefficiency.[5]

Election of the Prime Minister

Between 1885 and 1947 in the Empire of Japan, the prime minister was not elected, but responsible to, chosen and appointed by the Emperor. In practice, the Genrō (元老) usually nominated a candidate for appointment. The Imperial Diet (帝国議会, Teikoku-gikai) and its elected lower house, the House of Representatives, which were set up in 1890 according to the Imperial Constitution, had no constitutionally guaranteed role in the formation of cabinets.[6]

Since 1947, the Prime Minister has been chosen in the "designation election of the prime minister" (内閣総理大臣指名選挙, Naikaku sōridaijin shimei senkyo) in the National Diet. It is held after a cabinet has submitted its resignation – the outgoing cabinet remains as caretaker cabinet until the Imperial inauguration ceremony of a new prime minister –; a cabinet must resign en masse under the constitution (Articles 69 and 70) 1. always on convocation of the first Diet after a general election of the House of Representatives, 2. if the post of prime minister has fallen vacant – that includes cases when the prime minister is permanently incapacitated, e.g. by illness, kidnapping or defection –, or 3. if a no-confidence vote in the House of Representatives is not answered by the dissolution of the chamber. Though both Houses of the Diet vote in two-round elections to select a prime minister, the House of Representatives has the decisive vote: If the two Houses vote for different candidates (as they did in 1948, 1989, 1998, 2007 and 2008), a procedure in the joint committee of both houses (両院協議会, Ryōin Kyōgikai) may reach a consensus; but eventually the candidate of the House of Representatives becomes that of the whole Diet and thereby prime minister-designate. The designated prime minister must still be ceremonially appointed by the Emperor in the Imperial Investiture (親任式, Shinnin-shiki) to enter office; but unlike some heads of state, the Emperor has no reserve power to appoint anyone other than the person elected by the Diet.

In 2001, LDP president and Prime Minister Junichirō Koizumi instituted an advisory council to investigate the possibility of introducing direct popular election of the prime minister in a constitutional revision.[7]

Latest results

2020 House of Representatives by-election

The April 26 by-election in Shizuoka's 4th district was won by former prefectural assemblyman Yōichi Fukazawa (LDP – Kōmeitō). With 61% of the vote, he easily beat opposition candidate Ken Tanaka (I – CDP, DPFP, JCP, SDP; 35%), a former prefectural assembly member from Tokyo, and two other candidates to fill the seat vacated by Yoshio Mochizuki's death in December.[8]

2019 House of Councillors by-election

The October 27 by-election in Saitama to fill the vacancy created by Motohiro Ōno's (DPFP) resignation was won by previous governor and former DPJ House of Representatives member Kiyoshi Ueda who had been an independent since his move from national to prefectural politics in 2003. The only other candidate was Takashi Tachibana for the anti-NHK party.[9][10]

2019 House of Councillors regular election

Results[11] summary:

- Proportional tier (1 nationwide constituency, 50 seats), turnout 48.79%

- LDP 33 candidates, 35.4% of votes, 19 seats (38% of seats)

- CDP 22 candidates, 15.8%, 8 seats (16%)

- Komeito 17 candidates, 13.1%, 7 seats (14%)

- Ishin 14 candidates, 9.8%, 5 seats (10%)

- JCP 26 candidates, 9.0%, 4 seats (8%)

- DPFP 14 candidates, 7.0%, 3 seats (6%)

- Reiwa Shinsengumi 9 candidates, 4.6%, 2 seats (4%) and gained legal status as national-level political party (>2% of votes)

- SDP 4 candidates, 2.1%, 1 seat (2%)

- N-Koku 4 candidates, 1.97%, 1 seat (2%)

- 4 other parties (aggregate) 12 candidates, 1.4%, no seats

- Majoritarian tier (45 constituencies, 74 seats), turnout 48.80%

- Governing parties (LDP+Komeito): 56 candidates, 47.5 % of votes, 45 seats (60.8% of seats)

- Centre-left opposition (CDP+DPFP+JCP+SDP): 51 candidates, 30.0 %, 15 seats (20.3%)

- Independents: 31 candidates (many of them jointly supported by the centre-left alliance in single-member constituencies) 10.6 %, 9 seats (12.2%, all of them centre-left opposition)

- Ishin: 8 candidates, 7.3%, 5 seats (6.8%)

- N-Koku: 37 candidates, 3.0%, no seats, but gained legal party status

- Others (aggregate: Reiwa Shinsengumi & 5 other parties) 32 candidates, 1.6 %, no seats

2019 House of Representatives by-elections

The LDP lost both April 2019 by-elections, in Okinawa to the left opposition, in Osaka to the Ishin no Kai.

2017 House of Representatives general election

| ||||||||||||||

| Parties | Constituency | PR Block | Total seats | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | ±pp | Seats | Votes | % | ±pp | Seats | Seats | ± | % | ±pp | |||

| Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) | 26,719,032 | 48.21 | 218 | 18,555,717 | 33.28 | 66 | 284 | 61.08 | ||||||

| Komeitō (NKP) | 832,453 | 1.50 | 8 | 6,977,712 | 12.51 | 21 | 29 | 6.24 | ||||||

| Governing coalition | 27,551,485 | 49.71 | 226 | 25,533,429 | 45.79 | 87 | 313 | 67.31 | ||||||

| Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan (CDP) | 4,852,097 | 8.75 | New | 18 | 11,084,890 | 19.88 | New | 37 | 55 | 11.83 | ||||

| Japanese Communist Party (JCP) | 4,998,932 | 9.02 | 1 | 4,404,081 | 7.90 | 11 | 12 | 2.58 | ||||||

| Social Democratic Party (SDP) | 634,719 | 1.15 | 1 | 941,324 | 1.69 | 1 | 2 | 0.43 | ||||||

| Liberalist coalition | 10,485,748 | 18.92 | – | 20 | 16,430,295 | 29.47 | – | 49 | 69 | 14.84 | ||||

| Kibō no Tō (Party of Hope) | 11,437,601 | 20.64 | New | 18 | 9,677,524 | 17.36 | New | 32 | 50 | 10.75 | ||||

| Nippon Ishin no Kai (JIP) | 1,765,053 | 3.18 | 3 | 3,387,097 | 6.07 | 8 | 11 | 2.37 | ||||||

| The third coalition | 13,202,654 | 23.82 | – | 21 | 13,064,621 | 23.43 | – | 40 | 61 | 13.12 | ||||

| Happiness Realization Party (HRP) | 159,171 | 0.29 | – | 0 | 292,084 | 0.52 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | |||||

| New Party Daichi | – | – | – | – | 226,552 | 0.41 | – | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | ||||

| No Party to Support | – | – | – | – | 125,019 | 0.22 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | |||||

| Party for Japanese Kokoro (PJK) | – | – | – | – | 85,552 | 0.15 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | |||||

| Others | 52,080 | 0.03 | – | 0 | – | – | – | – | 0 | 0.00 | ||||

| Independents | 3,970,946 | 7.16 | 22 | – | – | – | – | 22 | 4.73 | |||||

| Total | 55,422,087 | 100.00 | – | 289 | 55,757,552 | 100.00 | – | 176 | 465 | 100.00 | – | |||

Malapportionment

In the 1980s, apportionment of electoral districts still reflected the distribution of the population in the years following World War II, when only one-third of the people lived in urban areas and two thirds lived in rural areas. In the next forty-five years, the population became more than three-quarters urban, as people deserted rural communities to seek economic opportunities in Tokyo and other large cities. The lack of reapportionment led to a serious underrepresentation of urban voters. Urban districts in the House of Representatives were increased by five in 1964, bringing nineteen new representatives to the lower house; in 1975 six more urban districts were established, with a total of twenty new representatives allocated to them and to other urban districts. Yet great inequities remained between urban and rural voters.

In the early 1980s, as many as five times the votes were needed to elect a representative from an urban district compared with those needed for a rural district. Similar disparities existed in the prefectural constituencies of the House of Councillors. The Supreme Court had ruled on several occasions that the imbalance violated the constitutional principle of one person-one vote. The Supreme Court mandated the addition of eight representatives to urban districts and the removal of seven from rural districts in 1986. Several lower house districts' boundaries were redrawn. Yet the disparity was still as much as three urban votes to one rural vote.

After the 1986 change, the average number of persons per lower house representative was 236,424. However, the figure varied from 427,761 persons per representative in the fourth district of Kanagawa Prefecture, which contains the large city of Yokohama, to 142,932 persons in the third district of largely rural and mountainous Nagano Prefecture.

The 1993 reform government under Hosokawa Morihiro introduce a new electoral system whereby 200 members (reduced to 180 beginning with the 2000 election) are elected by proportional representation in multi-member districts or "blocs" while 300 are elected from single-candidate districts.[12]

Still, according to the October 6, 2006 issue of the Japanese newspaper Daily Yomiuri, "the Supreme Court followed legal precedent in ruling Wednesday that the House of Councillors election in 2004 was held in a constitutionally sound way despite a 5.13-fold disparity in the weight of votes between the nation's most densely and most sparsely populated electoral districts".

The 2009 general House of Representatives election was the first unconstitutional lower house election under the current electoral system introduced in 1994 (parallel voting and "small" FPTP single-member electoral districts/"Kakumander"). In March 2011, the Grand Bench (daihōtei) of the Supreme Court ruled that the maximum discrepancy of 2.30 in voting weight between the Kōchi 3 and Chiba 4 constituencies in the 2009 election was in violation of the constitutionally guaranteed equality of all voters. As in previous such rulings on unconstitutional elections (1972, 1980, 1983 and 1990 Representatives elections, 1992 Councillors election), the election is not invalidated, but the imbalance has to be corrected by the Diet through redistricting and/or reapportionment of seats between prefectures.[13]

In 2016, a panel of experts proposed to introduce the [John Quincy] Adams apportionment method (method of smallest divisors) for apportioning House of Representatives seats to prefectures. The reform is planned to be implemented after the 2020 census figures are available and not expected to take effect before 2022.[14] In the meantime, another redistricting and apportionment passed in 2017 is designed to keep the maximum malapportionment ratio in the House of Representatives below 2. In the FPTP tier, it changes 97 districts and cuts six without adding any; in the proportional tier, four "blocks" lose a seat each; the total number of seats in the lower house is cut to 465, 289 majoritarian seats and 176 proportional seats.[15]

The malapportionment in the 2010[16] and 2013[17] regular House of Councillors elections was ruled unconstitutional (or "in an unconstitutional state") by the Supreme Court, and has been reduced by a 2015 reapportionment below 3 (at least in government statistics from census data which is regular and standardized but lags behind resident registration statistics and the actual number of eligible voters; using the latter, the maximum malapportionment in the 2016 election remained slightly above 3[18][19]).

The following table lists the 10 electoral districts with the highest and lowest number of registered voters per member elected for each chamber of the National Diet according to the voter statistics as of September 2016 released by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications – it takes into account the lowering of the voting age and the district reforms to both houses of the Diet in effect since the 2014 and 2016 elections, but not the 2017 redistricting/reapportionment effective from the next House of Representatives election.

| House of Representatives | House of Councillors | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowest vote weight | Highest vote weight | Lowest vote weight | Highest vote weight | ||||||

| # | District | Registered voters | District | Registered voters | District | Registered voters per member elected |

District | Registered voters per member elected |

# |

| 1 | Tokyo 1 | 514,974 | Fukushima 4 | 233,491 | Saitama | 1,015,543 | Fukui | 328,772 | 1 |

| 2 | Hokkaidō 1 | 505,510 | Miyagi 5 | 234,373 | Niigata | 978,686 | Saga | 346,727 | 2 |

| 3 | Tokyo 3 | 504,929 | Kagoshima 5 | 240,056 | Miyagi | 975,466 | Yamanashi | 353,402 | 3 |

| 4 | Tokyo 5 | 498,903 | Tottori 1 | 240,874 | Kanagawa | 951,735 | Kagawa | 417,082 | 4 |

| 5 | Hyōgo 6 | 492,173 | Nagasaki 3 | 242,165 | Tokyo | 937,470 | Wakayama | 419,011 | 5 |

| 6 | Tokyo 6 | 490,674 | Tottori 2 | 242,194 | Osaka | 915,000 | Akita | 448,236 | 6 |

| 7 | Tokyo 19 | 488,494 | Nagasaki 4 | 242,303 | Nagano | 885,638 | Toyama | 452,822 | 7 |

| 8 | Tokyo 22 | 486,965 | Aomori 3 | 244,007 | Chiba | 871,110 | Miyazaki | 466,829 | 8 |

| 9 | Saitama 3 | 483,014 | Mie 4 | 244,825 | Gifu | 850,190 | Yamagata | 475,419 | 9 |

| 10 | Tokyo 23 | 481,206 | Iwate 3 | 246,272 | Tochigi | 827,368 | Ishikawa | 481,027 | 10 |

Prefectural and local elections

Prefectural assemblies and governors, as well as mayors and assemblies in municipalities, are elected for four-year terms. In April 1947, all local elections in the 46 prefectures (excluding Okinawa, then under US military rule) and all their municipalities were held at the same time in "unified local elections" (tōitsu chihō senkyo). Since then, some gubernatorial and mayoral elections, and most assembly elections, have stayed on this original four-year cycle. Most governors and mayors are now elected on different schedules as the four-year cycle "resets" upon the resignation, death or removal of a sitting governor or mayor. Some assembly election cycles have also shifted due to assembly dissolutions or mergers of municipalities. In the last unified local elections in April 2015, 10 of 47 governors, 41 of 47 prefectural assemblies, 222 mayors and 689 municipal assemblies were scheduled to be elected.

Unified elections

As of 2015, the major contests in the unified local elections are as follows:

| Prefecture | Governor | Assembly | Designated city races |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hokkaido | ♦ | ♦ | Sapporo mayor Sapporo assembly |

| Aomori | ♦ | ||

| Akita | ♦ | ||

| Yamagata | ♦ | ||

| Tochigi | ♦ | ||

| Gunma | ♦ | ||

| Saitama | ♦ | Saitama assembly | |

| Chiba | ♦ | Chiba assembly | |

| Kanagawa | ♦ | ♦ | Yokohama assembly Kawasaki assembly Sagamihara mayor Sagamihara assembly |

| Niigata | ♦ | Niigata assembly | |

| Toyama | ♦ | ||

| Ishikawa | ♦ | ||

| Fukui | ♦ | ♦ | |

| Yamanashi | ♦ | ||

| Nagano | ♦ | ||

| Gifu | ♦ | ||

| Shizuoka | ♦ | Shizuoka mayor Hamamatsu mayor Hamamatsu assembly | |

| Aichi | ♦ | Nagoya assembly | |

| Mie | ♦ | ♦ | |

| Shiga | ♦ | ||

| Kyoto | ♦ | Kyoto assembly | |

| Osaka | ♦ | Osaka assembly Sakai assembly | |

| Hyogo | ♦ | Kobe assembly | |

| Nara | ♦ | ♦ | |

| Wakayama | ♦ | ||

| Tottori | ♦ | ♦ | |

| Shimane | ♦ | ♦ | |

| Okayama | ♦ | Okayama assembly | |

| Hiroshima | ♦ | Hiroshima mayor Hiroshima assembly | |

| Yamaguchi | ♦ | ||

| Tokushima | ♦ | ♦ | |

| Kagawa | ♦ | ||

| Ehime | ♦ | ||

| Kōchi | ♦ | ||

| Fukuoka | ♦ | ♦ | Fukuoka assembly |

| Saga | ♦ | ||

| Nagasaki | ♦ | ||

| Kumamoto | ♦ | Kumamoto assembly | |

| Oita | ♦ | ♦ | |

| Miyazaki | ♦ | ||

| Kagoshima | ♦ |

Although Tokyo's metropolitan governor and assembly elections are currently held on separate schedules, 21 of the 23 special wards of Tokyo follow the unified election schedule for their assembly elections, the only exceptions being Katsushika and Adachi. The majority of Tokyo's special wards follow separate cycles for their mayoral elections. Tokyo elected its governor as part of the unified elections until 2011, but was forced to hold a 2012 election and 2014 election due to the resignations of Shintaro Ishihara and Naoki Inose.

Iwate Prefecture, Miyagi Prefecture and Fukushima Prefecture are no longer on the unified election cycle due to the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, which delayed their elections.

Other major local election cycles

- Since 1971, Ibaraki Prefecture has held its prefectural assembly elections in the December preceding the unified election, making this election a regular leading indicator of the nationwide elections in the following April. The 2014 Ibaraki election was held on the same day as the 2014 Japanese general election.

- Approximately 193 new municipalities were created in a wave of "Heisei mergers" effective in April 2005. Their first municipal elections were held around this time, and coincided with the Chiba and Akita gubernatorial elections and the Nagoya mayoral election, creating a second major local election cycle sometimes referred to as the "mini unified local elections."

- Okinawa Prefecture and most of its local governments continue to follow a four-year cycle that began following repatriation to Japan in June 1972, with several exceptions (including the city of Naha). Okinawa elections generally occur in the year following the unified elections; the next is scheduled for June 2016.

2020/21 electoral calendar

Upcoming elections due to expiring terms (additional early elections may be caused by resignations, deaths, votes of no confidence, dissolutions, recalls etc.):

- National elections

- October 2020, April 2021: By-elections for vacant majoritarian seats in the National Diet if necessary

- Before autumn 2021 (end of term 2021/10/21): general election of [all] members of the House of Representatives

- Summer 2022 (end of term 2022/7/25): regular election of [124] members of the House of Councillors

- Prefectural elections

- Gubernatorial elections

- 2020/7/5 (announcement 6/18, end of term 7/30):[21] Tokyo

- 2020/7/12: Kagoshima (announcement 6/25, end of term 7/27)[22]

- 2020/10/25 (official announcement 10/8): Okayama (end of term 11/11)[23], Toyama (end of term 11/8)[24]

- Autumn 2020: Tochigi (end of term 12/8)

- First half of 2021: Gifu (end of term 2/5)[25], Yamagata (end of term 2/13)[26], Chiba, Akita, Shizuoka

- Assembly general elections

- Summer 2021: Tokyo (end of term 2021/7/22)[27]

- Gubernatorial elections

- Major municipal elections (designated major cities only)

- Mayoral elections

- First half of 2021: Nagoya, Saitama, Chiba

- Assembly general elections

- First half of 2021: Kitakyūshū (end of term 2/9)[28], Shizuoka

- Municipality-wide referendum

- 2020/11/1 (Tentative! Still subject to potential short-term adjustments due to the Coronavirus pandemic and final approval by the prefectural assembly of Osaka and the municipal assembly of Osaka City): Referendum to replace Osaka City and its current (sub-municipal, administrative) wards with four (city-level) special wards of Osaka prefecture, see Osaka Metropolis plan[29][30][31]

- Mayoral elections

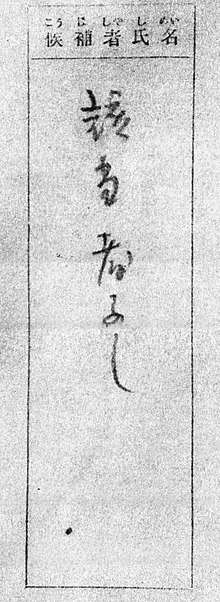

Ballots, voting machines and early voting

Votes in national and most local elections are cast by writing the candidate's or party's name on a blank ballot paper. In elections for the House of Representatives voters fill in two ballots, one with the name of their preferred district candidate and one with their preferred party in the proportional representation block. For the House of Councillors, the district vote is similar (in SNTV multi-member districts, several candidates can be elected, but every voter has only one vote). But in the proportional vote for the House of Councillors votes are cast for a party list (to determine how many proportional seats a party receives) or a candidate (which additionally influences which candidates are elected from a party's list).[32]

Ballots that cannot unambiguously be assigned to a candidate are not considered invalid, but are assigned to all potentially intended candidates proportionally to the unambiguous votes each candidate has received. These so-called "proportional fractional votes" (按分票, Anbun-hyō) are rounded to the third decimal.[33] For example, if "Yamada A" and "Yamada B" both stood in an election and there were 1500 unambiguous votes: 1000 for "Yamada A" and 500 for "Yamada B"; five ambiguous votes for "Yamada" would then count for Yamada A as 5×1000/1500=3.333 votes, and for Yamada B as 5×500/1500=1.667 votes.

In 2002, passage of an electronic voting law[34] allowed for the introduction of electronic voting machines in local elections.[35] The first machine vote took place in Niimi, Okayama in June 2002.[36] In 2003, a system for early voting (期日前投票制度, Kijitsu-mae tōhyō seido) was introduced.[37] In the 2009 Japanese general election, a record number of more than 10 million Japanese voted early.[38]

Walkovers

In Japan, walkovers in elections are called Mutōhyō tōsen (無投票当選), "[being] elected without vote". And there is literally no vote held in a walkover in Japan, no way to vote "no" or abstain explicitly: If there are only as many candidates in an election as there are seats/offices at the start of the legal election period ("official announcement": kōji (公示) in national elections; kokuji (告示) in prefectural and municipal elections), they are declared the winners. But the otherwise applicable moratorium period after regular elections on recall attempts does not apply after a walkover. (Recalls are a two-/three-step procedure: first, supporters of a recall must collect a sufficient number of signatures; if they do, a referendum is held on whether or not to recall the incumbent; only if that is accepted by a majority, a fresh election is scheduled.) Article 100 of the Public Offices Election Law deals with walkovers,[39] there are additional walkover provisions for subnational elections in the Local Autonomy Law.

Walkovers have become widespread in prefectural and municipal elections in recent years; in the 2019 unified local elections, out of 2277 seats up in 945 electoral districts for 41 prefectural assemblies, a record 612 seats are won by walkovers in a total of 371 districts or 39% of all electoral districts. In one extreme case, a rural single-member electoral district to the Shimane prefectural assembly, there hasn't been a contested election in 31 years (the whole Heisei period).[40][41]

See also

- Electoral calendar

- Election

- Political funding in Japan

- Japanese Diet

References

- "Diet enacts law lowering voting age to 18 from 20". The Japan Times.

- "Diet passes controversial bill adding seats to Japan's Upper House for first time in nearly half a century". The Japan Times. Jul 18, 2018. Retrieved Apr 27, 2019.

- Jiji Press, July 4, 2019: 特定枠、れいわ・労働も利用【19参院選】, retrieved September 18, 2019.

- Mainichi Shimbun, July 5, 2019: 2019参院選 公示 特定枠に5候補者 比例に導入、優先的に当選, retrieved September 18, 2019.

- Nishikawa, Yoko (2010-04-04). "Nearly half of Japan's voters don't support any party". Reuters. Retrieved 2010-04-05.

- The Ally From The Far East - Japan in World War 1. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- Kantei: Advisory Council to Consider the Direct Election of the Prime Minister

- NHK選挙Web, April 27, 2020: 衆院補選 静岡4区 (House of Rep.s by-election Shizuoka district 4), retrieved May 28, 2020.

- Asahi Shimbun, October 27, 2019: 参院埼玉補選、無所属で前知事の上田清司氏が初当選, retrieved October 28, 2019

- Tōkyō Shimbun, October 28, 2019: 参院埼玉補選 上田氏当選 投票率 低調20・81%, retrieved October 28, 2019

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications: Complete results of the 25th regular election (in Japanese), candidate totals by party pp. 2–5, turnout statistics pp. 6–13, seat totals by party pp. 14–16, vote totals & shares by party pp. 19–22 [pdf page numbers are off +2], retrieved September 18, 2019.

- Batto, NF., Huang, C., Tan, AC. and Cox, G. (Ed.) (2016) Batto, NF., Huang, C., Tan, AC. and Cox, G. (Ed.) (2016) Mixed-Member Electoral Systems in Constitutional Context: Taiwan, Japan and Beyond. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Jiji Tsūshin, March 23, 2011: 09年衆院選は違憲状態=1人別枠方式「平等に反する」-廃止要請・最高裁大法廷

- nikkei.com, March 15, 2017: 衆院定数10減決まる 選挙制度改革まとめ

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications: 衆議院小選挙区の区割りの改定等について ("On the changes to House of Representatives single-member districts" [but covers the changes to proportional districts, too]) (in Japanese)

- Asahi Shimbun, Asia & Japan Watch, October 18, 2012: Japan's 2 Diet chambers both ruled all but 'unconstitutional' Archived 2012-10-22 at the Wayback Machine

- The Japan Times, November 26, 2014: Supreme Court assails vote disparity in 2013 election but doesn’t nullify results

- Mainichi Shimbun, July 12, 2016: 2016参院選:「1票の格差」一斉提訴 最大3.08倍、無効訴え 14高裁・支部

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, December 27, 2019: Voter statistics as of September 2, 2016 [covers districts of both houses of the National Diet], p.16 (in Japanese)

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, December 27, 2016: Voter statistics as of September 2, 2016, p. 8 (in Japanese)

- Tokyo metropolitan government, electoral commission: elections in Tokyo held in Reiwa 2 (=2020), retrieved February 22, 2020. (in Japanese)

- Kagoshima prefectural government, electoral commission, March 24, 2020: 令和2年7月12日執行鹿児島県知事選挙, retrieved April 1, 2020. (in Japanese)

- Okayama prefectural government, electoral commission, May 28, 2020: 岡山県知事選挙の日程を決定しました ("Okayama prefectural gubernatorial election schedule has been decided."), retrieved July 18, 2020. (in Japanese)

- Toyama prefectural government, electoral commission: 選挙日程 ("electoral calendar" [of municipal, national and prefectural elections in Toyama]), retrieved July 18, 2020. (in Japanese)

- Gifu prefectural government, electoral commission: 3.国会議員・岐阜県知事・岐阜県議会議員の任期満了日 ("3. Ends of terms of members of the National Diet, Gifu prefectural governor, members of the Gifu prefectural assembly"), retrieved July 18, 2020. (in Japanese)

- Yamagata prefectural government, electoral commission: 任期満了日調(衆議・参議・県知事・県議・市町村長・市町村議) ("ends of terms (HR, HC, pref. governor, pref. assembly, city/town/village mayors, city/town/village assemblies)"), retrieved July 18, 2020. (in Japanese)

- Tokyo metropolitan government, electoral commission: 任期満了日(定数)一覧 ("list of ends of terms and magnitudes" [for national, prefectural and municipal elected offices in Tokyo], retrieved July 18, 2020. (in Japanese)

- Fukuoka prefectural government, electoral commission: ends of terms of municipal mayors and assemblies in Fukuoka, retrieved July 18, 2020. (in Japanese)

- Nihon Keizai Shimbun, June 19, 2020: 大阪都構想の制度案決定 法定協で可決、住民投票へ (Ōsaka-to-kōsō no seido-an kettei/hōteikyō de kaketsu, jūmin tōhyō e, "Osaka metropolis plan draft outline passed/approved in the joint conference [of Osaka prefecture's and Osaka city's governments] designated by law, towards referendum"), retrieved June 24, 2020.

- The Mainichi, November 23, 2019: Referendum on Osaka metropolis plan set for 2020, English translation of Mainichi Shimbun, November 22, 2019: 都構想の制度案の大枠固まる 20年の住民投票確実 6回目の法定協, retrieved June 24, 2020.

- Jiji Press, June 19, 2020: Osaka Panel Approves Final Plan for City Reorganization, retrieved June 24, 2020.

- Kamiya, Setsuko, "Some election campaign rules outdated, quirky", Japan Times, 11 December 2012, p. 3

- "FAQ>按分(あんぶん)票とは何ですか。" (in Japanese). Izumi, Osaka city electoral commission. Retrieved June 5, 2013.

- "地方公共団体の議会の議員及び長の選挙に係る電磁的記録式投票機を用いて行う投票方法等の特例に関する法律". Archived from the original on 2010-03-01. Retrieved 2009-09-26.

- MIC: 電磁的記録式投票制度について

- Kōbe Shimbun, June 28, 2002: 全国初の電子投票ルポ 岡山・新見市

- MIC: 期日前投票制度

- The Japan Times, August 30, 2009: Record-high 10.9 million voters cast early ballots

- kōshoku-senkyo-hō in the MIC e-gov database of legal texts

- NHK News, March 29, 2019: 41道府県議選 無投票当選者が過去最多 Archived 2019-03-29 at the Wayback Machine ("41 prefectural assembly elections: number of walkovers at all-time high"), retrieved March 30, 2019.

- The Japan Times editorial, March 22, 2019: Low turnout, poor competition mar local elections