Delaware River

The Delaware River is a major river on the Atlantic coast of the United States. It drains an area of 14,119 square miles (36,570 km2) in four U.S. states: Delaware (itself technically named after the river), New Jersey, New York and Pennsylvania. Rising in two branches in New York state's Catskill Mountains, the river flows 419 miles (674 km) into Delaware Bay where its waters enter the Atlantic Ocean near Cape May in New Jersey and Cape Henlopen in Delaware. Not including Delaware Bay, the river's length including its two branches is 388 miles (624 km).[1][2] The Delaware River is one of nineteen "Great Waters" recognized by the America's Great Waters Coalition.[3]

| Delaware River | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Delaware River at New Hope, Pennsylvania | |

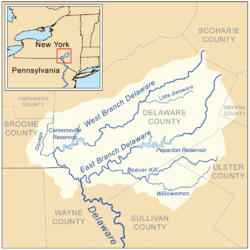

Map of the Delaware River watershed, showing major tributaries and cities | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware and Maryland |

| Cities | Margaretville, NY, Delhi, NY, Deposit, NY, Hancock, NY, Callicoon, NY, Lackawaxen, PA, Port Jervis, NY, Stroudsburg, PA, Easton, PA, New Hope, PA, Trenton, NJ, Camden, NJ, Philadelphia, PA, Chester, PA, Wilmington, DE , Salem, NJ, Dover, DE |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | West Branch |

| • location | Mount Jefferson, Town of Jefferson, Schoharie County, New York, United States |

| • coordinates | 42°27′12″N 74°36′26″W |

| • elevation | 2,240 ft (680 m) |

| 2nd source | East Branch |

| • location | Grand Gorge, Town of Roxbury, Delaware County, New York, United States |

| • coordinates | 42°21′26″N 74°30′42″W |

| • elevation | 1,560 ft (480 m) |

| Source confluence | |

| • location | Town of Hancock, Delaware County, New York, United States |

| • coordinates | 41°56′20″N 75°16′46″W |

| • elevation | 880 ft (270 m) |

| Mouth | Delaware Bay |

• location | Delaware, United States |

• coordinates | 39°25′13″N 75°31′11″W |

• elevation | 0 ft (0 m) |

| Length | 301 mi (484 km) |

| Basin size | 14,119 sq mi (36,570 km2) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Trenton |

| • average | 13,100 cu ft/s (370 m3/s) |

| • minimum | 4,310 cu ft/s (122 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 329,000 cu ft/s (9,300 m3/s) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Port Jervis |

| • average | 7,900 cu ft/s (220 m3/s) |

| • minimum | 1,420 cu ft/s (40 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 52,900 cu ft/s (1,500 m3/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Neversink River, Pequest River, Musconetcong River |

| • right | Lehigh River, Schuylkill River, Christina River |

| Type | Scenic, Recerational |

The Delaware River rises in two main branches that descend from the western flank of the Catskill Mountains in New York. The West Branch begins near Mount Jefferson in the Town of Jefferson in Schoharie County. The river's East Branch begins at Grand Gorge in Delaware County. These two branches flow west and merge near Hancock in Delaware County, and the combined waters flow as the Delaware River south. Through its course, the Delaware River forms the boundaries between Pennsylvania and New York, the entire boundary between New Jersey and Pennsylvania, and most of the boundary between Delaware and New Jersey. The river meets tide-water at the junction of Morrisville, Pennsylvania, and Trenton, New Jersey, at the Falls of the Delaware. The river's navigable, tidal section served as a conduit for shipping and transportation that aided the development of the industrial cities of Trenton, Camden and Philadelphia. The mean freshwater discharge of the Delaware River into the estuary of Delaware Bay is 11,550 cubic feet per second (327 m3/s).

Before the arrival of European settlers, the river was the homeland of the Lenape Native Americans. They called the river Lenapewihittuk, or Lenape River, and Kithanne, meaning the largest river in this part of the country.[4]

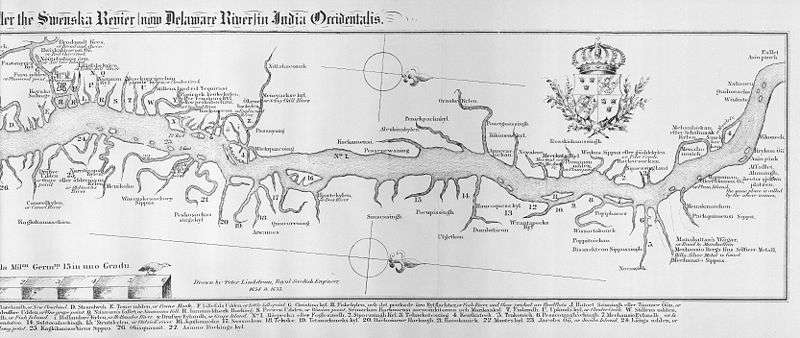

In 1609 the river was visited by a Dutch East India Company expedition led by Henry Hudson. Hudson, an English navigator, was hired to find a western route to Cathay (present-day China), but his discoveries set the stage for Dutch colonization of North America in the 17th century. Early Dutch and Swedish settlements were established along the lower section of river and Delaware Bay. Both colonial powers called the river the South River, compared to the Hudson River, which was known as the North River. After the English expelled the Dutch and took control of the New Netherland colony in 1664, the river was renamed Delaware after Sir Thomas West, 3rd Baron De La Warr, an English nobleman and the Virginia colony's first royal governor who defended the colony during the First Anglo-Powhatan War.

Origin of the name

The Delaware River is named in honor of Thomas West, 3rd Baron De La Warr (1577–1618), an English nobleman and the Virginia colony's first royal governor who defended the colony during the First Anglo-Powhatan War.[5] Lord de la Warr waged a punitive campaign to subdue the Powhatan after they had killed the colony's council president, John Ratcliffe, and attacked the colony's fledgling settlements.[6][7] Lord de la Warr arrived with 150 soldiers in time to prevent colony's original settlers at Jamestown from giving up and returning to England and is credited with saving the Virginia colony.[5] The name of barony (later an earldom) is pronounced as in the current spelling form "Delaware" (/ˈdɛləwɛər/ (![]()

It has often been reported that the river and bay received the name "Delaware" after English forces under Richard Nicolls expelled the Dutch and took control of the New Netherland colony in 1664.[9][10] However, the river and bay were known by the name Delaware as early as 1641.[11] The state of Delaware was originally part of the William Penn's Pennsylvania colony. In 1682, the Duke of York granted Penn's request for access to the sea and leased him the territory along the western shore of Delaware Bay which became known as the "Lower Counties on the Delaware."[12] In 1704, these three lower counties were given political autonomy to form a separate provincial assembly, but shared its provincial governor with Pennsylvania until the two colonies separated on June 15, 1776 and remained separate as states after the establishment of the United States. The name also came to be used as a collective name for the Lenape, a Native American people (and their language) who inhabited an area of the basins of the Susquehanna River, Delaware River, and lower Hudson River in the northeastern United States at the time of European settlement.[13] As a result of disruption following the French & Indian War, American Revolutionary War and later Indian removals from the eastern United States, the name "Delaware" has been spread with the Lenape's diaspora to municipalities, counties and other geographical features in the American Midwest and Canada.[14]

Watershed

The Delaware River's drainage basin has an area of 14,119 square miles (36,570 km2) and encompasses 42 counties and 838 municipalities in five U.S. states—New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Delaware.[15]:9 This total area constitutes approximately 0.4% of the land mass in the United States.[15]:9 In 2001, the watershed was 18% agricultural land, 14% developed land, and 68% forested land. [15]:vi

There are 216 tributary streams and creeks—an estimated 14,057 miles of streams and creeks—in the watershed.[15]:p.11,25 While the watershed is home to 4.17 million people according to the 2000 Federal Census, these bodies of water provide drinking water to 17 million people—roughly 6% of the population of the United States.[15]:vi, 9 The waters of the Delaware River's basin are used to sustain "fishing, transportation, power, cooling, recreation, and other industrial and residential purposes."[15]:9 It is the 33rd largest river in the United States in terms of flow, but the nation's most heavily used rivers in daily volume of tonnage.[15]:p.11 The average annual flow rate of the Delaware is 11,700 cubic feet per second at Trenton, New Jersey.[15]:9 With no dams or impediments on the river's main stem, the Delaware is one of the few remaining large free-flowing rivers in the United States.[15]:11

Course

West Branch of the Delaware

The West Branch of the Delaware River (also called the Mohawk Branch) spans approximately 90 miles (140 km) from the northern Catskill Mountains to where it joins in confluence with the Delaware River's East Branch at Hancock, New York. The last 6 miles (9.7 km) forms part of the boundary between New York and Pennsylvania.

The West Branch rises in Schoharie County, New York at 1,886 feet (575 m) above sea level, near Mount Jefferson, and flows tortuously through the plateau in a deep trough. The branch flows generally southwest, entering Delaware County and flowing through the towns of Stamford and Delhi. In southwestern Delaware County it flows in an increasingly winding course through the mountains, generally southwest. At Stilesville the West Branch was impounded in the 1960s to form the Cannonsville Reservoir, the westernmost of the reservoirs in the New York City water system. It is the most recently constructed New York City reservoir and began serving the city in 1964. Draining a large watershed of 455 square miles (1,180 km2), the reservoir's capacity is 95.7 billion US gallons (362,000,000 m3). This water flows over halfway through the reservoir to enter the 44-mile (71 km) West Delaware Tunnel in Tompkins, New York. Then it flows through the aqueduct into the Rondout Reservoir, where the water enters the 85 miles (137 km) Delaware Aqueduct, that contributes to roughly 50% of the city's drinking water supply. At Deposit, on the border between Broome and Delaware counties, it turns sharply to the southeast and is paralleled by New York State Route 17. It joins the East Branch at 880 feet (270 m) above sea level at Hancock to form the Delaware.

East Branch of the Delaware

Similarly, the East Branch begins from a small pond south of Grand Gorge in the town of Roxbury in Delaware County, flowing southwest toward its impoundment by New York City to create the Pepacton Reservoir, the largest reservoir in the New York City water supply system. Its tributaries are the Beaver Kill River and the Willowemoc Creek which enter into the river ten miles (16 km) before the West Branch meets the East Branch. The confluence of the two branches is just south of Hancock.

The East Branch and West Branch of the Delaware River parallel each other, both flowing in a southwesterly direction.

Upper Delaware Valley

From Hancock, New York, the river flows between the northern The Poconos in Pennsylvania, and the lowered shale beds north of the Catskills. The river flows down a broad Appalachian valley, passing Hawk's Nest overlook on the Upper Delaware Scenic Byway. The river flows southeast for 78 miles through rural regions along the New York-Pennsylvania border to Port Jervis and the Shawangunk Mountains.

The Minisink

At Port Jervis, New York, it enters the Port Jervis trough. At this point, the Walpack Ridge deflects the Delaware into the Minisink Valley, where it follows the southwest strike of the eroded Marcellus Formation beds along the Pennsylvania–New Jersey state line for 25 miles (40 km) to the end of the ridge at Walpack Bend in the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area.[16][17] The Minisink is a buried valley where the Delaware flows in a bed of glacial till that buried the eroded bedrock during the last glacial period. It then skirts the Kittatinny ridge, which it crosses at the Delaware Water Gap, between nearly vertical walls of sandstone, quartzite, and conglomerate, and then passes through a quiet and charming country of farm and forest, diversified with plateaus and escarpments, until it crosses the Appalachian plain and enters the hills again at Easton, Pennsylvania. From this point it is flanked at intervals by fine hills, and in places by cliffs, of which the finest are the Nockamixon Rocks, 3 miles (5 km) long and above 200 feet (61 m) high.

The Appalachian Trail, which traverses the ridge of Kittatinny Mountain in New Jersey, and Blue Mountain in Pennsylvania, crosses the Delaware River at the Delaware Water Gap near Columbia, New Jersey.

Central Delaware Valley

At Easton, Pennsylvania, the Lehigh River enters the Delaware. At Trenton there is a fall of 8 feet (2.4 m).

The Lower Delaware and Tide-Water

Below Trenton the river flows between Philadelphia and New Jersey before becoming a broad, sluggish inlet of the sea, with many marshes along its side, widening steadily into its great estuary, Delaware Bay.

The Delaware River constitutes the boundary between Delaware and New Jersey. The Delaware-New Jersey border is actually at the easternmost river shoreline within the Twelve-Mile Circle of New Castle, rather than mid-river or mid-channel borders, causing small portions of land lying west of the shoreline, but on the New Jersey side of the river, to fall under the jurisdiction of Delaware. The rest of the borders follow a mid-channel approach.

History

At the time of the arrival of the Europeans in the early 17th century, the area near the Delaware River was inhabited by the Native American Lenape people. They called the Delaware River "Lenape Wihittuck", which means "the rapid stream of the Lenape".[18] The Delaware River played a key factor in the economic and social development of the Mid-Atlantic region. In the seventeenth century it provided the conduit for colonial settlement by the Dutch (New Netherland), the Swedish (New Sweden). Beginning in 1664, the region became an English possession as settlement by Quakers established the colonies of Pennsylvania (including present-day Delaware) and West Jersey. In the eighteenth century, cities like Philadelphia, Camden (then Cooper's Ferry), Trenton and Wilmington, and New Castle were established upon the Delaware and their continued commercial success into the present day has been dependent on access to the river for trade and power. The river provided the path for the settlement of northeastern Pennsylvania's Lehigh Valley, and northwestern New Jersey by German Palatine immigrants—a population that became key in the agricultural development of the region.

Washington's crossing of the Delaware River

Perhaps the most famous "Delaware Crossing" was George Washington's crossing of the Delaware River with the Continental Army on the night of December 25–26, 1776, leading to a successful surprise attack and victory against the Hessian troops occupying Trenton, New Jersey on the morning of December 26.

Canals

The magnitude of the commerce of Philadelphia has made the improvements of the river below that port of great importance. Small improvements were attempted by Pennsylvania as early as 1771. Commerce was once important on the upper river, primarily prior to railway competition (1857).

- The Delaware Division of the Pennsylvania Canal, running parallel with the river from Easton to Bristol, opened in 1830.

- The Delaware and Raritan Canal, which runs along the New Jersey side of the Delaware River from Bulls Island, New Jersey to Trenton, unites the waters of the Delaware and Raritan rivers as it empties the waters of the Delaware River via the canal outlet in New Brunswick. This canal water conduit is still used as a water supply source by the State of New Jersey.

- The Morris Canal (now abandoned and almost completely filled in) and the Delaware and Hudson Canal connected the Delaware and Hudson rivers.

- The Chesapeake and Delaware Canal joins the waters of the Delaware with those of the Chesapeake Bay.

Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area

The Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area came about as a result of the failure of a controversial plan to build a dam on the Delaware River at Tocks Island, just north of the Delaware Water Gap to control water levels for flood control and hydroelectric power generation. The dam would have created a 37-mile (60 km) lake in the center of present park for use as a reservoir. Starting in 1960, the present day area of the Recreation Area was acquired for the Army Corps of Engineers through eminent domain. Between 3,000 and 5,000 dwellings were demolished, including historical sites, and about 15,000 people were displaced by the project.

Because of massive environmental opposition, dwindling funds, and an unacceptable geological assessment of the dam's safety, the government transferred the property to the National Park Service in 1978. The National Park Service found itself as the caretaker of the previously endangered territory, and with the help of the federal government and surrounding communities, developed recreational facilities and worked to preserve the remaining historical structures.[19][20]

The nearby Shawnee Inn,[21][22] was identified in the 1990s as the only resort along the banks of the Delaware River.[23][24]

America Rivers, an environmental advocacy group, named the Delaware River as the river of the year for 2020.

Commerce

Wine regions

In 1984, the U.S. Department of the Treasury authorized the creation of a wine region or "American Viticultural Area" called the Central Delaware Valley AVA located in southeastern Pennsylvania and New Jersey. The wine appellation includes 96,000 acres (38,850 ha) surrounding the Delaware River north of Philadelphia and Trenton, New Jersey.[25] In Pennsylvania, it consists of the territory along the Delaware River in Bucks County; in New Jersey, the AVA spans along the river in Hunterdon County and Mercer County from Titusville, New Jersey, just north of Trenton, northward to Musconetcong Mountain.[26] As of 2013, there are no New Jersey wineries in the Central Delaware Valley AVA.[26][27]

Shipping

In the "project of 1885" the U.S. government undertook systematically the formation of a 26-foot (7.9 m) channel 600 feet (180 m) wide from Philadelphia to deep water in Delaware Bay. The River and Harbor Act of 1899 provided for a 30-foot (9.1 m) channel 600 feet (180 m) wide from Philadelphia to the deep water of the bay.[28]

Since 1941, the Delaware River Main Channel was maintained at a depth of 40 ft (12 m). There is an effort underway to deepen the 102.5-mile stretch of this federal navigation channel, from Philadelphia and Camden to the mouth of the Delaware Bay to 45 feet.[29][30][31][32][33][34]

The Delaware River port complex refers to the ports and energy facilities along the river in the tri-state PA-NJ-DE Delaware Valley region. They include the Port of Salem, the Port of Wilmington, the Port of Chester, the Port of Paulsboro, the Port of Philadelphia and the Port of Camden. Combined they create one of the largest shipping areas of the United States. In 2015, the ports of Philadelphia, Camden, and Wilmington handled 100 million tons of cargo from 2,243 ship arrivals, and supported 135,000 direct or indirect jobs. The biggest category of imports was fruit, carried by 490 ships, followed by petroleum, and containers, with 410 and 381 ships, respectively. The biggest category of exports was of shipping was containers, with 470 ships. [35] In 2016, 2,427 ships arrived at Delaware River port facilities. Fruit ships were counted at 577, petroleum at 474, and containerized cargo at 431.[36]

At one time it was a center for petroleum and chemical products and included facilities such as the Delaware City Refinery, the Dupont Chambers Works, Oceanport Terminal at Claymont, the Marcus Hook Refinery, the Trainer Refinery, the Paulsboro Asphalt Refinery,[37][38][39] Paulsboro Refinery, Eagle Point Refinery, and Sunoco Fort Mifflin. As of 2011, crude oil was the largest single commodity transported on the Delaware River, accounting for half of all annual cargo tonnage.[31][40]

Crossings

The Delaware River is a major barrier to travel between New Jersey and Pennsylvania. Most of the larger bridges are tolled only westbound, and are owned by the Delaware River and Bay Authority, Delaware River Port Authority, Burlington County Bridge Commission or Delaware River Joint Toll Bridge Commission.

Environmental issues

New York City water supply

After New York City built 15 reservoirs to supply water to the city's growing population, it was unable to obtain permission to build an additional five reservoirs along the Delaware River's tributaries. As a result, in 1928 the city decided to draw water from the Delaware River, putting them in direct conflict with villages and towns across the river in Pennsylvania which were already using the Delaware for their water supply. The two sides eventually took their case to the U.S. Supreme Court, and in 1931, New York City was allowed to draw 440 million US gallons (1,700,000 m3) of water a day from the Delaware and its upstream tributaries.

Pollution

The Delaware River has been attached to areas of high pollution. The Delaware River in 2012 was named the 5th most polluted river in the United States, explained by PennEnvironment[41] and Environment New Jersey.[42] The activist groups claim that there is about 7–10 million pounds of toxic chemicals flowing through the waterways due to dumping by DuPont Chambers Works. PennEnviornment also claims that the pollutants in the river can cause birth defects, infertility among women, and have been linked to cancer.[41]

In 2015, the EPA saw the Delaware River as a concern for mass pollution especially in the Greater Philadelphia and Chester, Pennsylvania area. The EPA was involved after accusations that the river met standards made illegal by the Clean Water Act. In complying with the Clean Water Act, the EPA involved the Delaware County Regional Water Authority (DELCORA) where they set up a plan to spend around $200 million to help rid the waterway of about 740 million gallons of sewage and pollution. DELCORA was also fined about $1.4 million for allowing the Delaware River to have so much pollution residing in the river in the first place and for not complying with the Clean Water Act.[43]

The Clean Water Act explains the importance of low pollution for human and species health. One of the sectors in the Clean Water Act explains how conditions of the river should be stable enough for human fishing and swimming. Even though the river has had success with the cleanup of pollution, the Delaware River still does not meet that standard of swimmable or fishable conditions in the Philadelphia/ Chester region.

Flooding

With the failure of the dam project to come to fruition, the lack of flood control on the river left it vulnerable, and it has experienced a number of serious flooding events as the result of snow melt or rain run-off from heavy rainstorms. Record flooding occurred in August 1955, in the aftermath of the passing of the remnants of two separate hurricanes over the area within less than a week: first Hurricane Connie and then Hurricane Diane, which was, and still is, the wettest tropical cyclone to have hit the northeastern United States. The river gauge at Riegelsville, Pennsylvania recorded an all-time record crest of 38.85 feet (11.84 m) on August 19, 1955.

More recently, moderate to severe flooding has occurred along the river. The same gauge at Riegelsville recorded a peak of 30.95 feet (9.43 m) on September 23, 2004, 34.07 feet (10.38 m) on April 4, 2005, and 33.62 feet (10.25 m) on June 28, 2006, all considerably higher than the flood stage of 22 feet (6.7 m).[44]

Since the upper Delaware basin has few population centers along its banks, flooding in this area mainly affects natural unpopulated flood plains. Residents in the middle part of the Delaware basin experience flooding, including three major floods in the three years (2004–2006) that have severely damaged their homes and land. The lower part of the Delaware basin from Philadelphia southward to the Delaware Bay is tidal and much wider than portions further north, and is not prone to river-related flooding (although tidal surges can cause minor flooding in this area).

The Delaware River Basin Commission, along with local governments, is working to try to address the issue of flooding along the river. As the past few years have seen a rise in catastrophic floods, most residents of the river basin feel that something must be done. The local governments have worked in association with FEMA to address many of these problems, however, due to insufficient federal funds, progress is slow.[45]

Major oil spills

A number of oil spills have taken place in the Delaware over the years.[46][47][48]

- Jan 31, 1975 – around 11,172,000 US gallons (42,290 m3) of crude oil spilled from the Corinthos tanker

- Sep 28, 1985 – 435,000 US gallons (1,650 m3) of crude oil spilled from the Grand Eagle tanker after running aground on Marcus Hook Bar

- Jun 24, 1989 – 306,000 US gallons (1,160 m3) of crude oil spilled from the Presidente Rivera tanker after running aground on Claymont Shoal

- Nov 26, 2004 – 265,000 US gallons (1,000 m3) of crude oil spilled from the Athos 1 tanker; the tanker's hull had been punctured by a submerged, discarded anchor at the Port of Paulsboro. In 2020, the Supreme Court ruled that Citgo had failed to provide a safe berth for the vessel and was therefore jointly responsible for clean up costs. The company was ordered to pay $143 million dollars.

Atlantic sturgeon

The National Marine Fisheries Service is considering designating sixteen rivers as endangered habitat for the Atlantic Sturgeon which would require more attention to be given to uses of the rivers that affect the fish.[49]

National Wild and Scenic River

The river is part of the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System.

See also

- Foul Rift, rapids just south of Belvidere, New Jersey

- Geography of Pennsylvania

- List of crossings of the Delaware River

- List of rivers of Delaware

- List of rivers of New Jersey

- List of rivers of New York

- List of rivers of Pennsylvania

- Partnership for the Delaware Estuary

- Tocks Island

- Upper Delaware Scenic and Recreational River

- Washington Crossing (disambiguation)

Notes

- The main stem from Hancock, New York to the head of Delaware Bay is 301 miles (484 km).

- U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline data. The National Map Archived March 29, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, accessed April 1, 2011

- National Wildlife Federation (August 18, 2010). "America's Great Waters Coalition". Archived from the original on August 15, 2011. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- Heckewelder, John; Du Ponceau, Peter S. (1834), "Names which the Lenni Lenape or Delaware Indians, who once inhabited this country, had given to Rivers, Streams, Places, &c.", Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, 4: 351–396, doi:10.2307/1004837, JSTOR 1004837

- Pollard, Albert Frederick (1899). "West, Thomas (1577–1618)". In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 60. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 344–345.

- Tyler, Lyon Gardiner, ed. (1915). Encyclopedia of Virginia Biography. I. New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Company. pp. 33–34.

- Grenier, John (2005). The First Way of War: The American War-Making of the Frontier, 1607–1814. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 24–25. ISBN 0-521-84566-1.

- Random House Dictionary

- World Digital Library. Articles about the Transfer of New Netherland on the 27th of August, Old Style, Anno 1664 Archived January 26, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved March 21, 2013

- Versteer, Dingman (editor). "New Amsterdam Becomes New York" in The New Netherland Register. Volume 1 No. 4 and 5 (April/May 1911): 49-64.

- Evelin, Robert. A direction for Adventurers With small stock to get two for one, and good land freely : And for Gentleman, and all Servants, Labourers, and Artificers to live plentifully, And the true Description of the healthiest, pleasantest and richest plantation of New Albion in North Virginia. (London, s.n., 1641).

- Munroe, John A. (2006). "Chapter 3. The Lower Counties On The Delaware". History of Delaware. Newark, Delaware: University of Delaware Press. p. 45. ISBN 0-87413-947-3.

- Schutt, Amy C. (2007). Peoples of the River Valleys: The Odyssey of the Delaware Indians. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-3993-5.

- Weslager, Charles A. (1990). The Delaware Indians: A History. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-1494-0.

- Philadelphia Water Department. "Moving from Assessment to Protection…The Delaware River Watershed Source Water Protection Plan" (PWSID #1510001) Archived July 28, 2013, at the Wayback Machine (June 2007). Retrieved July 17, 2013.

- White, Ron W.; Monteverde, Donald H. (February 2006). "Karst in the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area" (PDF). Unearthing New Jersey Vol. 2, No. 1. New Jersey Geological Survey. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 10, 2008. Retrieved June 7, 2008.

- White, I.C.; Chance, H.M. (1882). The geology of Pike and Monroe counties. Second Geol. Surv. of Penna. Rept. of Progress, G6. Harrisburg. pp. 17, 73–80, 114–115.

- Delaware Place Names Archived August 11, 2017, at the Wayback Machine United States Geological Survey

- Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area (pp. 7–8), Obiso, Laura, 2008.

- Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area Archived August 3, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, njskylands.com.

- "Shawnee Marking Golden Season". The Daily Record. Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania. June 17, 1960.

- Squeri, p. 182.

- Fodor's national parks and seashores of the east (1 ed.). New York: Fodor's Travel Publications. 1994. p. 164.

- Shea, Barbara (September 11, 1994). "Let the current set the pace at the Delaware Water Gap". The Courier-News. Somerville, New Jersey.

- The Wine Institute. "American Viticultural Areas by State" Archived January 27, 2008, at the Wayback Machine (2008). Retrieved February 5, 2008.

- Code of Federal Regulations. Section 9.49 Central Delaware Valley. Archived April 22, 2013, at the Wayback Machine (27 CFR 9.49) from Title 27 - Alcohol, Tobacco Products and Firearms. CHAPTER I - ALCOHOL AND TOBACCO TAX AND TRADE BUREAU, DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY. SUBCHAPTER A - LIQUORS. PART 9 - AMERICAN VITICULTURAL AREAS. Subpart C - Approved American Viticultural Areas. Retrieved June 30, 2013.

- New Jersey Division of Alcoholic Beverage Control. "New Jersey ABC list of wineries, breweries, and distilleries" (February 5, 2013). Retrieved May 2, 2013. An analysis was done comparing a list of wineries provided by the New Jersey Division of Alcoholic Beverage Control with the AVA's description in the Code of Federal Regulations.

-

- United States Army Corps of Engineers. Delaware River Main Channel Deepening Archived July 29, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved July 25, 2013.

- Ruch, Robert J. Ruch (Lt. Col.), District Engineer, Philadelphia District. Delaware River Main Channel Deepening Project Archived September 23, 2015, at the Wayback Machine Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission (January 20, 2005). Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Delaware River Main Channel Deepening Project Archived September 3, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. (May 2012). Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- Delaware Riverkeeper. The Delaware River Main Channel Deepening Project: Background Archived July 16, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- "Epic Effort to Deepen Delaware River Shipping Channel Nears End". www.njspotlight.com – NJ Spotlight. Archived from the original on May 28, 2016. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- "Murky Bottom: Will Deeper Delaware River Make Philly More Competitive?". www.njspotlight.com – NJ Spotlight. May 25, 2016. Archived from the original on May 28, 2016. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- "Delaware River Ports Fight For Market as Dredging Project Nears Completion". www.njspotlight.com – NJ Spotlight. May 23, 2016. Archived from the original on May 28, 2016. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on April 11, 2019. Retrieved April 9, 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Paulsboro Refinery". June 26, 2013. Archived from the original on June 22, 2015. Retrieved April 11, 2019.

- Tuttle, Robert (February 3, 2017). "America's Biggest Asphalt Plant Is Shutting When the Country Might Need It Most". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on February 3, 2017. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

- Renshaw, Jarrett (January 18, 2017). "Axeon plans to shutter New Jersey asphalt refinery: sources". Reuters. Archived from the original on February 5, 2017. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

- American Waterways. New Jersey A key link in the nation's import/export economy. Retrieve July 26, 2013.

- "Environmental group: Delaware River tops list of most polluted waterways". Bucks Local News. March 29, 2012. Archived from the original on January 28, 2020. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- Augenstein, Seth (April 5, 2012). "Delaware River is 5th most polluted river in U.S., environmental group says". NJ.com News. Archived from the original on January 28, 2020. Retrieved March 30, 2019.

- "Settlement to Improve Water Quality in Delaware River, Philadelphia-Area Creeks". U.S. EPA Region 3 Water Protection Division. August 20, 2015. Archived from the original on January 28, 2020. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- USGS Archived February 13, 2007, at the Wayback Machine See Also: State of New Jersey: Recent flooding events in the Delaware River basin Archived September 16, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Delaware River Basin Commission (July 20, 2005). "Delaware River Basin Commission's Role in Flood Loss Reduction Efforts." Archived August 18, 2006, at the Wayback Machine West Trenton, NJ.

- "Athos 1 Oil Spill". University of Delaware Sea Grant Program. November 3, 2005. Archived from the original on April 27, 2006. Retrieved April 29, 2006.

- "1985 Grand Eagle Oil Spill". University of Delaware Sea Grant Program. December 16, 2004. Archived from the original on April 18, 2006. Retrieved April 29, 2006.

- "Presidente Rivera Spill – June 24, 1989". University of Delaware Sea Grant Program. December 8, 2004. Archived from the original on June 19, 2006. Retrieved April 29, 2006.

- "Feds Move to Protect Endangered Atlantic Sturgeon in Delaware River - NJ Spotlight". www.njspotlight.com. June 8, 2016. Archived from the original on June 11, 2016. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

References

- Devastation on the Delaware: Stories and Images of the Deadly Flood of 1955 (2005, Word Forge Books, Ferndale, PA) The only comprehensive documentary of this weather disaster in the Delaware River Valley.

External links

![]()

- Delaware Riverkeeper Network

- Delaware River Basin Commission

- Delaware River Vessel Reporting System

- National Park Service: Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area

- National Park Service: Upper Delaware Scenic & Recreational River

- National Park Service: Lower Delaware Wild & Scenic River

- U.S. Geological Survey: NJ stream gaging stations

- U.S. Geological Survey: NY stream gaging stations

- U.S. Geological Survey: PA stream gaging stations

Historical content

- Marine Railway and Sectional Floating Dry Dock, Delaware River, Philadelphia, 1893 by D.J. Kennedy, Historical Society of Pennsylvania

- Winter on the River Delaware, 1856. Shows "U.S.S. Prowhatan" by D.J. Kennedy, HSP

- "Map of the South River in New Netherland" from ca. 1639 via the World Digital Library

- Socioeconomic Value of the Delaware River Basin in Delaware, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania

Encyclopedias

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.