Pilgrims (Plymouth Colony)

The Pilgrims were the English settlers who came to North America on the Mayflower and established the Plymouth Colony in what is today Plymouth, Massachusetts named after the final departure port of Plymouth, Devon. Their leadership came from the religious congregations of Brownists, or Separatist Puritans, who had fled religious persecution in England for the tolerance of 17th-century Holland in the Netherlands.

| Part of a series on |

| Calvinism |

|---|

|

|

Background |

|

|

They held Puritan Calvinist religious beliefs but, unlike most other Puritans, they maintained that their congregations should separate from the English state church. They eventually determined to establish a new settlement in the New World and arranged with investors to fund them. They established Plymouth Colony in 1620, which became the second successful English settlement in America, following the founding of Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607. The Pilgrims' story became a central theme in the history and culture of the United States.[1]

History

The core of the group called "the Pilgrims" were brought together around 1605 when they quit the church of England to form Separatist congregations in the north of England, led by John Robinson, Richard Clyfton, and John Smyth. Their congregations held Brownist beliefs—that true churches were voluntary, democratic communities, not whole Christian nations—as taught by Robert Browne, John Greenwood, and Henry Barrow. As separatists, they held that their differences with the Church of England were irreconcilable and that their worship should be independent of the trappings, traditions, and organization of a central church.[2][3]

The Separatist movement was controversial. Under the Act of Uniformity 1559, it was illegal not to attend official Church of England services, with a fine of one shilling (£0.05; about £19 today)[4] for each missed Sunday and holy day. The penalties included imprisonment and larger fines for conducting unofficial services. The Seditious Sectaries Act of 1593 was specifically aimed at outlawing the Brownists. Under this policy, the London Underground Church from 1566, and then Robert Browne and his followers in Norfolk during the 1580s, were repeatedly imprisoned. Henry Barrow, John Greenwood, and John Penry were executed for sedition in 1593. Browne had taken his followers into exile in Middelburg, and Penry urged the London Separatists to emigrate in order to escape persecution, so after his death they went to Amsterdam.

During much of Brewster's tenure (1595–1606), the Archbishop was Matthew Hutton. He displayed some sympathy to the Puritan cause, writing to Robert Cecil, Secretary of State to James I in 1604:

The Puritans though they differ in Ceremonies and accidentes, yet they agree with us in substance of religion, and I thinke all or the moste parte of them love his Majestie, and the presente state, and I hope will yield to conformitie. But the Papistes are opposite and contrarie in very many substantiall pointes of religion, and cannot but wishe the Popes authoritie and popish religion to be established.[5]

Many Puritans had hoped that a reconciliation would be possible when James came to power which would allow them independence, but the Hampton Court Conference of 1604 denied nearly all of the concessions which they had requested—except for an updated English translation of the Bible. The same year, Richard Bancroft became Archbishop of Canterbury and launched a campaign against Puritanism. He suspended 300 ministers and fired 80, which led some of them to found Separatist churches. Robinson, Clifton, and their followers founded a Brownist church, making a covenant with God "to walk in all his ways made known, or to be made known, unto them, according to their best endeavours, whatsoever it should cost them, the Lord assisting them".[6]

Archbishop Hutton died in 1606 and Tobias Matthew was appointed as his replacement. He was one of James's chief supporters at the 1604 conference,[7] and he promptly began a campaign to purge the archdiocese of non-conforming influences, both Puritans and those wishing to return to the Catholic faith. Disobedient clergy were replaced, and prominent Separatists were confronted, fined, and imprisoned. He is credited with driving people out of the country who refused to attend Anglican services.[8][9]

William Brewster was a former diplomatic assistant to the Netherlands. He was living in the Scrooby manor house while serving as postmaster for the village and bailiff to the Archbishop of York. He had been impressed by Clyfton's services and had begun participating in services led by John Smyth in Gainsborough, Lincolnshire.[10] After a time, he arranged for a congregation to meet privately at the Scrooby manor house. Services were held beginning in 1606 with Clyfton as pastor, John Robinson as teacher, and Brewster as the presiding elder. Shortly after, Smyth and members of the Gainsborough group moved on to Amsterdam.[11] Brewster was fined £20 (about £4.35 thousand today[4]) in absentia for his non-compliance with the church.[12] This followed his September 1607 resignation from the postmaster position,[13] about the time that the congregation had decided to follow the Smyth party to Amsterdam.[2][14]

Scrooby member William Bradford of Austerfield kept a journal of the congregation's events which was eventually published as Of Plymouth Plantation. He wrote concerning this time period:

But after these things they could not long continue in any peaceable condition, but were hunted & persecuted on every side, so as their former afflictions were but as flea-bitings in comparison of these which now came upon them. For some were taken & clapt up in prison, others had their houses besett & watcht night and day, & hardly escaped their hands; and the most were faine to flie & leave their howses & habitations, and the means of their livelehood.[2]

Leiden

The Pilgrims moved to the Netherlands around 1607/08. They lived in Leiden, Holland, a city of 30,000 inhabitants,[15] residing in small houses behind the "Kloksteeg" opposite the Pieterskerk. The success of the congregation in Leiden was mixed. Leiden was a thriving industrial center,[16] and many members were able to support themselves working at Leiden University or in the textile, printing, and brewing trades. Others were less able to bring in sufficient income, hampered by their rural backgrounds and the language barrier; for those, accommodations were made on an estate bought by Robinson and three partners.[17] Bradford wrote of their years in Leiden:

For these & other reasons they removed to Leyden, a fair & bewtifull citie, and of a sweete situation, but made more famous by ye universitie wherwith it is adorned, in which of late had been so many learned man. But wanting that traffike by sea which Amerstdam injoyes, it was not so beneficiall for their outward means of living & estats. But being now hear pitchet they fell to such trads & imployments as they best could; valewing peace & their spirituall comforte above any other riches whatsoever. And at length they came to raise a competente & comforteable living, but with hard and continuall labor.[18]

William Brewster had been teaching English at the university, and Robinson enrolled in 1615 to pursue his doctorate. There he participated in a series of debates, particularly regarding the contentious issue of Calvinism versus Arminianism (siding with the Calvinists against the Remonstrants).[19] Brewster acquired typesetting equipment about 1616 in a venture financed by Thomas Brewer, and began publishing the debates through a local press.[20]

The Netherlands, however, was a land whose culture and language were strange and difficult for the English congregation to understand or learn. They found the Dutch morals much too libertine, and their children were becoming more and more Dutch as the years passed. The congregation came to believe that they faced eventual extinction if they remained there.[21]

Decision to leave Holland

By 1617, the congregation was stable and relatively secure, but there were ongoing issues which needed to be resolved. Bradford noted that many members of the congregation were showing signs of early aging, compounding the difficulties which some had in supporting themselves. A few had spent their savings and so gave up and returned to England, and the leaders feared that more would follow and that the congregation would become unsustainable. The employment issues made it unattractive for others to come to Leiden, and younger members had begun leaving to find employment and adventure elsewhere. Also compelling was the possibility of missionary work in some distant land, an opportunity that rarely arose in a Protestant stronghold.[22]

Bradford lists some of the reasons which the Puritans had to leave, including the discouragements that they faced in the Netherlands and the hope of attracting others by finding "a better, and easier place of living", the children of the group being "drawn away by evil examples into extravagance and dangerous courses", and the "great hope, for the propagating and advancing the gospel of the kingdom of Christ in those remote parts of the world."[22] Edward Winslow's list was similar. In addition to the economic worries and missionary possibilities, he stressed that it was important for the people to retain their English identity, culture, and language. They also believed that the English Church in Leiden could do little to benefit the larger community there.[23]

At the same time, there were many uncertainties about moving to such a place as America, as stories had come back about failed colonies. There were fears that the native people would be violent, that there would be no source of food or water, that they might be exposed to unknown diseases, and that travel by sea was always hazardous. Balancing all this was a local political situation which was in danger of becoming unstable. The truce was faltering in the Eighty Years' War, and there was fear over what the attitudes of Spain might be toward them.[22]

Possible destinations included Guiana on the northeast coast of South America where the Dutch had established Essequibo colony, or another site near the Virginia settlements. Virginia was an attractive destination because the presence of the older colony might offer better security and trade opportunities; however, they also felt that they should not settle too near, since that might inadvertently duplicate the political environment back in England. The London Company administered a territory of considerable size in the region, and the intended settlement location was at the mouth of the Hudson River (which instead became the Dutch colony of New Netherland). This plan allayed their concerns of social, political, and religious conflicts, but still promised the military and economic benefits of being close to an established colony.[24]

Robert Cushman and John Carver were sent to England to solicit a land patent. Their negotiations were delayed because of conflicts internal to the London Company, but ultimately a patent was secured in the name of John Wincob on June 9 (Old Style)/June 19 (New Style), 1619.[25] The charter was granted with the king's condition that the Leiden group's religion would not receive official recognition.[26]

Preparations then stalled because of the continued problems within the London Company, and competing Dutch companies approached the congregation with the possibility of settling in the Hudson River area.[26] David Baeckelandt suggests that the Leiden group was approached by Englishman Matthew Slade, son-in-law of Petrus Placius, a cartographer for the Dutch East India Company. Slade was also a spy for the English Ambassador, and the Puritans' plans were therefore known both at court and among influential investors in the Virginia Company's colony at Jamestown.[27] Negotiations were broken off with the Dutch, however, at the encouragement of English merchant Thomas Weston, who assured them that he could resolve the London Company delays.[28] The London Company intended to claim the area explored by Hudson[27] before the Dutch could become fully established, and the first Dutch settlers did not arrive in the area until 1624.

Weston did come with a substantial change, telling the Leiden group that parties in England had obtained a land grant north of the existing Virginia territory to be called New England. This was only partially true; the new grant did come to pass, but not until late in 1620 when the Plymouth Council for New England received its charter. It was expected that this area could be fished profitably, and it was not under the control of the existing Virginia government.[28][29]

A second change was known only to parties in England who did not inform the larger group. New investors had been brought into the venture who wanted the terms altered so that, at the end of the seven-year contract, half of the settled land and property would revert to the investors. Also, there had been a provision which allowed each settler to have two days per week to work on personal business, but this provision had been dropped from the agreement without the knowledge of the Puritans.[28]

Amid these negotiations, William Brewster found himself involved with religious unrest emerging in Scotland. In 1618, King James had promulgated the Five Articles of Perth which were seen in Scotland as an attempt to encroach on their Presbyterian tradition. Brewster published several pamphlets that were critical of this law, and they were smuggled into Scotland by April 1619. These pamphlets were traced back to Leiden, and the English authorities unsuccessfully attempted to arrest Brewster. English ambassador Dudley Carleton became aware of the situation and began pressuring the Dutch government to extradite Brewster, and the Dutch responded by arresting Thomas Brewer the financier in September. Brewster's whereabouts remain unknown between then and the colonists' departure, but the Dutch authorities did seize the typesetting materials which he had used to print his pamphlets. Meanwhile, Brewer was sent to England for questioning, where he stonewalled government officials until well into 1620. He was ultimately convicted in England for his continued religious publication activities and sentenced in 1626 to a 14-year prison term.[30]

Preparations

Not all of the congregation were able to depart on the first trip. Many members were not able to settle their affairs within the time constraints, and the budget was limited for travel and supplies, and the group decided that the initial settlement should be undertaken primarily by younger and stronger members. The remainder agreed to follow if and when they could. Robinson would remain in Leiden with the larger portion of the congregation, and Brewster was to lead the American congregation. The church in America would be run independently, but it was agreed that membership would automatically be granted in either congregation to members who moved between the continents.

With personal and business matters agreed upon, the Puritans procured supplies and a small ship. Speedwell was to bring some passengers from the Netherlands to England, then on to America where it would be kept for the fishing business, with a crew hired for support services during the first year. The larger ship Mayflower was leased for transport and exploration services.[28][31]

Voyage

The Speedwell was originally named Swiftsure. It was built in 1577 at 60 tons and was part of the English fleet that defeated the Spanish Armada. It departed Delfshaven in July 1620 with the Leiden colonists, after a canal ride from Leyden of about seven hours.[32] It reached Southampton, Hampshire, and met with the Mayflower and the additional colonists hired by the investors. With final arrangements made, the two vessels set out on August 5 (Old Style)/August 15 (New Style).[31]

Soon after, the Speedwell crew reported that their ship was taking on water, so both were diverted to Dartmouth, Devon. The crew inspected Speedwell for leaks and sealed them, but their second attempt to depart got them only as far as Plymouth, Devon. The crew decided that Speedwell was untrustworthy, and her owners sold her; the ship's master and some of the crew transferred to the Mayflower for the trip. William Bradford observed that the Speedwell seemed "overmasted", thus putting a strain on the hull; and he attributed her leaking to crew members who had deliberately caused it, allowing them to abandon their year-long commitments. Passenger Robert Cushman wrote that the leaking was caused by a loose board.[33]

Atlantic crossing

Of the 120 combined passengers, 102 were chosen to travel on the Mayflower with the supplies consolidated. Of these, about half had come by way of Leiden, and about 28 of the adults were members of the congregation.[34] The reduced party finally sailed successfully on September 6 (Old Style)/September 16 (New Style), 1620.

Initially the trip went smoothly, but under way they were met with strong winds and storms. One of these caused a main beam to crack, and the possibility was considered of turning back, even though they were more than halfway to their destination. However, they repaired the ship sufficiently to continue using a "great iron screw" brought along by the colonists (probably a jack to be used for either house construction or a cider press).[35] Passenger John Howland was washed overboard in the storm but caught a top-sail halyard trailing in the water and was pulled back on board.

One crew member and one passenger died before they reached land. A child was born at sea and named Oceanus.[36][37]

Arrival in America

The Mayflower passengers sighted land on November 9, 1620 after enduring miserable conditions for about 65 days, and William Brewster led them in reading Psalm 100 as a prayer of thanksgiving. They confirmed that the area was Cape Cod within the New England territory recommended by Weston. They attempted to sail the ship around the cape towards the Hudson River, also within the New England grant area, but they encountered shoals and difficult currents around Cape Malabar (the old French name for Monomoy Island). They decided to turn around, and the ship was anchored in Provincetown Harbor by November 11/12.[36][38]

The Mayflower Compact

The charter was incomplete for the Plymouth Council for New England when the colonists departed England (it was granted while they were in transit on November 3/13).[29] They arrived without a patent; the older Wincob patent was from their abandoned dealings with the London Company. Some of the passengers, aware of the situation, suggested that they were free to do as they chose upon landing, without a patent in place, and to ignore the contract with the investors.[39][40]

A brief contract was drafted to address this issue, later known as the Mayflower Compact, promising cooperation among the settlers "for the general good of the Colony unto which we promise all due submission and obedience." It organized them into what was called a "civill body politick," in which issues would be decided by voting, the key ingredient of democracy. It was ratified by majority rule, with 41 adult male Pilgrims signing[41] for the 102 passengers (73 males and 29 females). Included in the company were 19 male servants and three female servants, along with some sailors and craftsmen hired for short-term service to the colony.[42] At this time, John Carver was chosen as the colony's first governor. It was Carver who had chartered the Mayflower and his is the first signature on the Mayflower Compact, being the most respected and affluent member of the group. The Mayflower Compact is considered to be one of the seeds of American democracy and one source has called it the world's first written constitution.[43][44][45]:90–91[46]

First landings

Thorough exploration of the area was delayed for more than two weeks because the shallop or pinnace (a smaller sailing vessel) which they brought had been partially dismantled to fit aboard the Mayflower and was further damaged in transit. Small parties, however, waded to the beach to fetch firewood and attend to long-deferred personal hygiene.

Exploratory parties were undertaken while awaiting the shallop, led by Myles Standish (an English soldier whom the colonists had met while in Leiden) and Christopher Jones. They encountered an old European-built house and iron kettle, left behind by some ship's crew, and a few recently cultivated fields, showing corn stubble.[47]

They came upon an artificial mound near the dunes which they partially uncovered and found to be an Indian grave. Farther along, a similar mound was found, more recently made, and they discovered that some of the burial mounds also contained corn. The colonists took some of the corn, intending to use it as seed for planting, while they reburied the rest. William Bradford later recorded in his book Of Plymouth Plantation that, after the shallop had been repaired,

They also found two of the Indian's houses covered with mats, and some of their implements in them; but the people had run away and could not be seen. Without permission they took more corn, and beans of various colours. These they brought away, intending to give them full satisfaction (payment) when they should meet with any of them, – as about six months afterwards they did.

And it is to be noted as a special providence of God, and a great mercy to this poor people, that they thus got seed to plant corn the next year, or they might have starved; for they had none, nor any likelihood of getting any, till too late for the planting season.

By December, most of the passengers and crew had become ill, coughing violently. Many were also suffering from the effects of scurvy. There had already been ice and snowfall, hampering exploration efforts; half of them died during the first winter.[48]

First contact

Explorations resumed on December 6/16. The shallop party headed south along the cape, consisting of seven colonists from Leiden, three from London, and seven crew; they chose to land at the area inhabited by the Nauset people (the area around Brewster, Chatham, Eastham, Harwich, and Orleans) where they saw some people on the shore who fled when they approached. Inland they found more mounds, one containing acorns which they exhumed, and more graves, which they decided not to dig. They remained ashore overnight and heard cries near the encampment. The following morning, they were attacked by Indians who shot at them with arrows. The colonists retrieved their firearms and shot back, then chased them into the woods but did not find them. There was no more contact with Indians for several months.[49]

The local Indians were already familiar with the English, who had intermittently visited the area for fishing and trade before Mayflower arrived. In the Cape Cod area, relations were poor following a visit several years earlier by Thomas Hunt. Hunt kidnapped 20 people from Patuxet (the site of Plymouth Colony) and another seven from Nausett, and he attempted to sell them as slaves in Europe. One of the Patuxet abductees was Squanto, who became an ally of the Plymouth Colony.

The Pokanokets also lived nearby and had developed a particular dislike for the English after one group came in, captured numerous people, and shot them aboard their ship. By this time, there had already been reciprocal killings at Martha's Vineyard and Cape Cod. But during one of the captures by the English, Squanto escaped to England and there became a Christian. When he came back, he found that most of his tribe had died from plague.[40][50]

Settlement

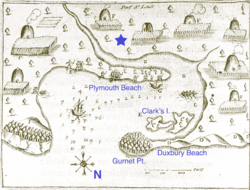

Continuing westward, the shallop's mast and rudder were broken by storms and the sail was lost. They rowed for safety, encountering the harbor formed by Duxbury and Plymouth barrier beaches and stumbling on land in the darkness. They remained at this spot for two days to recuperate and repair equipment. They named it Clark's Island for a Mayflower mate who first set foot on it.[51]

They resumed exploration on Monday, December 11/21 when the party crossed over to the mainland and surveyed the area that ultimately became the settlement. The anniversary of this survey is observed in Massachusetts as Forefathers' Day and is traditionally associated with the Plymouth Rock landing tradition. This land was especially suited to winter building because it had already been cleared, and the tall hills provided a good defensive position.

The cleared village was known as Patuxet to the Wampanoag people and was abandoned about three years earlier following a plague that killed all of its residents. The "Indian fever" involved hemorrhaging[52] and is assumed to have been fulminating smallpox. The outbreak had been severe enough that the colonists discovered unburied skeletons in the dwellings.[53]

The exploratory party returned to the Mayflower, anchored twenty-five miles (40 km) away,[54] having been brought to the harbor on December 16/26. Only nearby sites were evaluated, with a hill in Plymouth (so named on earlier charts)[55] chosen on December 19/29.

Construction commenced immediately, with the first common house nearly completed by January 9/19, 20 feet square and built for general use.[56] At this point, each single man was ordered to join himself to one of the 19 families in order to eliminate the need to build any more houses than absolutely necessary.[56] Each extended family was assigned a plot one-half rod wide and three rods long for each household member,[56] then each family built its own dwelling. Supplies were brought ashore, and the settlement was mostly complete by early February.[49][57]

When the first house was finished, it immediately became a hospital for the ill Pilgrims. Thirty-one of the company were dead by the end of February, with deaths still rising. Coles Hill became the first cemetery, on a prominence above the beach, and the graves were allowed to overgrow with grass for fear that the Indians would discover how weakened the settlement had actually become.[58]

Between the landing and March, only 47 colonists had survived the diseases that they contracted on the ship.[58] During the worst of the sickness, only six or seven of the group were able to feed and care for the rest. In this time, half the Mayflower crew also died.[40]

William Bradford became governor in 1621 upon the death of John Carver. On March 22, 1621, the Pilgrims of Plymouth Colony signed a peace treaty with Massasoit of the Wampanoags. The patent of Plymouth Colony was surrendered by Bradford to the freemen in 1640, minus a small reserve of three tracts of land. Bradford served for 11 consecutive years, and was elected to various other terms until his death in 1657.

The colony contained Bristol County, Plymouth County, and Barnstable County, Massachusetts. The Massachusetts Bay Colony was reorganized and issued a new charter as the Province of Massachusetts Bay in 1691, and Plymouth ended its history as a separate colony.

Etymology

Bradford's history

The first use of the word pilgrims for the Mayflower passengers appeared in William Bradford's Of Plymouth Plantation. As he finished recounting his group's July 1620 departure from Leiden, he used the imagery of Hebrews 11:13–16 about Old Testament "strangers and pilgrims" who had the opportunity to return to their old country but instead longed for a better, heavenly country.

So they lefte [that] goodly & pleasante citie, which had been ther resting place, nere 12 years; but they knew they were pilgrimes, & looked not much on these things; but lift up their eyes to ye heavens, their dearest cuntrie, and quieted their spirits.[31]

There is no record of the term Pilgrims being used to describe Plymouth's founders for 150 years after Bradford wrote this passage, except when quoting him. The Mayflower's story was retold by historians Nathaniel Morton (in 1669) and Cotton Mather (in 1702), and both paraphrased Bradford's passage and used his word pilgrims. At Plymouth's Forefathers' Day observance in 1793, Rev. Chandler Robbins recited this passage.[59]

Popular use

The name Pilgrims was probably not in popular use before about 1798, even though Plymouth celebrated Forefathers' Day several times between 1769 and 1798 and used a variety of terms to honor Plymouth's founders. The term Pilgrims was not mentioned, other than in Robbins' 1793 recitation.[60] The first documented use of the term that was not simply quoting Bradford was at a December 22, 1798 celebration of Forefathers' Day in Boston. A song composed for the occasion used the word Pilgrims, and the participants drank a toast to "The Pilgrims of Leyden".[61][62] The term was used prominently during Plymouth's next Forefather's Day celebration in 1800, and was used in Forefathers' Day observances thereafter.[63]

By the 1820s, the term Pilgrims was becoming more common. Daniel Webster repeatedly referred to "the Pilgrims" in his December 22, 1820 address for Plymouth's bicentennial which was widely read.[64] Harriet Vaughan Cheney used it in her 1824 novel A Peep at the Pilgrims in Sixteen Thirty-Six, and the term also gained popularity with the 1825 publication of Felicia Hemans's classic poem "The Landing of the Pilgrim Fathers".[65]

See also

- The Mayflower Society

- National Monument to the Forefathers

- Pieterskerk, Leiden

- Pilgrim Hall Museum

- Pilgrim Hill in Central Park in New York City has sitting on its crest the bronze statue of The Pilgrim, a stylized representation of one of the Pilgrims.

- Plymouth Colony

- Plymouth Rock

- Thanksgiving (United States)

- List of Mayflower passengers

- List of Mayflower passengers who died at sea November/December 1620

- List of Mayflower passengers who died in the winter of 1620–21

- Pilgrim Tercentenary half dollar

Notes

- Davis, Kenneth. C. "America's True History of Religious Tolerance". Smithsonian. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- Bradford & (1898), Book 1, Chapter 1.

- Tomkins, Stephen (2020). The Journey to the Mayflower. ISBN 9781473649101.

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved February 2, 2020.

- "The Bawdy Court: Exhibits – Belief and Persecution". University of Nottingham. Retrieved November 23, 2008.

- Tomkins, Stephen (2020). The Journey to the Mayflower. London and New York: Pegasus. p. 258. ISBN 9781643133676.

- Luckock, Herbert Mortimer (1882). Studies in the History of the Book of Common Prayer. London: Rivingtons. p. 219. OCLC 1071106. Retrieved November 23, 2008.

- Sheils, William Joseph (2004). "Matthew, Tobie (1544?–1628)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press.

- "English Dissenters: Barrowists". Ex Libris. January 1, 2008. Archived from the original on October 10, 2008. Retrieved November 23, 2008.

- Brown & (1891), pp. 181–182.

- Bassetlaw Museum. "Bassetlaw, Pilgrim Fathers Country". Retrieved November 23, 2008.

- Brown & (1891), p. 181.

- "Brewster, William". Encyclopædia Britannica (11 ed.). Cambridge University Press. 1911.

- Bradford & (1898), Book 1, Chapter 2.

- John (1895). The Pilgrim Fathers of New England and their Puritan Successors. Reprinted: 1970. Pasadena, Texas: Pilgrim Publications. pp. 118.

- Harreld, Donald. "The Dutch Economy in the Golden Age (16th–17th Centuries)". Economic History Services. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved November 11, 2008.

- "Contract of Sale, De Groene Poort". Leiden Pilgrim Archives. Archived from the original on October 13, 2007. Retrieved November 11, 2008.

- Bradford & (1898), Book 1, Chapter 3.

- See the Synod of Dort.

- Griffis & (1899), pp. 561–562.

- Bradford writes: "so as it was not only probably thought, but apparently seen, that within a few years more they would be in danger to scatter, by necessities pressing them, or sinke under their burdens, or both." (Of Plimoth Plantation, chapt. 4)

- Bradford & (1898), Book 1, Chapter 4.

- Winslow & (2003), pp. 62–63.

- Brown, John (1970). The Pilgrim Fathers of New England and their Puritan Successors. Pasadena, Texas: Pilgrim Publications. pp. 194.

- Kingsbury, Susan Myra, ed. (1906). The Records of the Virginia Company of London. 1. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. p. 228. Retrieved November 11, 2008.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Bradford & (1898), Book 1, Chapter 5.

- Baeckelandt, David. "The Flemish Influence On Henry Hudson", The Brussels Journal, January 1, 2011

- Bradford & (1898), Book 1, Chapter 6.

- "The Charter of New England: 1620". The Avalon Project. New Haven: Yale Law School. Retrieved November 11, 2008.

- Griffis & (1899), p. 575.

- Bradford & (1898), Book 1, Chapter 7.

- Brown, John (1895). The Pilgrim Fathers of New England and their Puritan Successors. Reprinted: 1970. Pasadena, Texas: Pilgrim Publications. pp. 185.

- "Project Gutenberg". Project Gutenberg. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- Deetz, Patricia Scott; Deetz, James F. "Passengers on the Mayflower: Ages & Occupations, Origins & Connections". The Plymouth Colony Archive Project. Retrieved November 10, 2008.

- Bangs, Jeremy Dupertuis (Winter 2003). "Pilgrim Life: Two Myths — Ancient and Modern". New England Ancestors. Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society. 4 (1): 52–55. ISSN 1527-9405. OCLC 43146397.

- Bradford & (1898), Book 1, Chapters 8–9.

- Fleming, Thomas (1963). One Small Candle. New York: W.W. Norton. pp. 89–90.

- Winslow & (2003), p. 64.

- Bradford and Winslow & (1865), pp. 5–6

- Bradford & (1898), Book 2, Anno 1620.

- Deetz, Patricia Scott; Fennell, Christopher (December 14, 2007). "Mayflower Compact, 1620". The Plymouth Colony Archive Project. Retrieved November 11, 2008.

- John (1895). The Pilgrim Fathers of New England and their Puritan Successors. Reprinted: 1970. Pasadena, Texas: Pilgrim Publications. pp. 196.

- Philbrick, Nathaniel, Mayflower: A Story of Courage, Community, and War p. 43, Viking, New York, NY, 2006. The Great Charter of the Virginia Company granted self governance to the Virginia Colony and could conceivably also be considered as a "seed of democracy", although it was not a contract in the sense of the Mayflower Compact.

- "John and Catherine Carver Archived July 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine," Pilgrim Hall Museum Web site. Retrieved January 28, 2011.

- Gayley, Charles Mills (1917). "Shakespeare and the Founders of Liberty in America". Internet Archive. Retrieved November 30, 2018.

- "The Fortnightly Club".

- Brown, John (1895). The Pilgrim Fathers of New England and their Puritan Successors. Reprinted: 1970. Pasadena, Texas: Pilgrim Publications. pp. 198.

- Klinkenborg, Verlyn (December 2011). "Why Was Life So Hard for the Pilgrims?". American History. 46 (5): 36.

- Bradford & (1898), Book 1, Chapter 10.

- Bradford and Winslow & (1865), pp. 90–91.

- John (1895). The Pilgrim Fathers of New England and their Puritan Successors. Reprinted: 1970. Pasadena, Texas: Pilgrim Publications. pp. 198.

- Bradford & (1898), Book 2, Anno 1622.

- Bradford & (1898), Book 2, Anno 1621.

- John (1895). The Pilgrim Fathers of New England and their Puritan Successors. Reprinted: 1970. Pasadena, Texas: Pilgrim Publications. pp. 200

- Deetz, Patricia Scott; Fennell, Christopher (December 14, 2007). "Smith's Map of New England, 1614". The Plymouth Colony Archive Project. Retrieved November 11, 2008.

- John (1895). The Pilgrim Fathers of New England and their Puritan Successors. Reprinted: 1970. Pasadena, Texas: Pilgrim Publications. pp. 202.

- Bradford and Winslow & (1865), pp. 60–65, 71–72.

- John (1895). The Pilgrim Fathers of New England and their Puritan Successors. Reprinted: 1970. Pasadena, Texas: Pilgrim Publications. pp. 203.

- Matthews & (1915), pp. 356–359.

- Matthews & (1915), pp. 297–311, 351.

- Matthews & (1915), pp. 323–327.

- "Toasts Drank at the Celebration of Our Country's Nativity". Massachusetts Mercury. Boston. December 28, 1798. pp. 2, 4.

- Matthews & (1915), pp. 312–350.

- Webster, Daniel (1854). Edward Everett (ed.). The Works of Daniel Webster. Vol. 1 (8th ed.). Boston: Brown, Little & Co. lxiv–lxv, 1–50. Retrieved November 30, 2008.

- Wolfson, Susan J., ed. (2000). Felicia Hemans. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 416–417. ISBN 978-0-691-05029-4.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

References

- Bradford, William; Edward Winslow, Henry Martyn Dexter, ed. (1865) [1622]. Mourt's Relation, or Journal of the Plantation at Plymouth. Boston: John Kimball Wiggin. OCLC 8978744. Retrieved November 28, 2008.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Bradford, William (1898) [1651]. Hildebrandt, Ted (ed.). Bradford's History "Of Plimoth Plantation" (PDF). Boston: Wright & Potter Printing Co. Retrieved November 28, 2008.

- Brown, Cornelius (1891). A History of Nottinghamshire. London: Elliot Stock. OCLC 4624771. Retrieved November 28, 2008.

- Griffis, William. "The Pilgrim Press in Leyden". New England Magazine. Boston: Warren F. Kellogg. 19/25 (January 1899): 559–575. Retrieved November 28, 2008.

- Matthews, Albert (1915). "The Term Pilgrim Fathers and Early Celebrations of Forefathers' Day". Publications of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts. Boston: The Society. 17: 293–391. Retrieved November 28, 2008.

- Winslow, Edward (2003). Johnson, Caleb (ed.). "Hypocrisy Unmasked" (PDF). MayflowerHistory.com. Retrieved November 28, 2008.

External links

![]()

- Pilgrim Archives, Searchable municipal and court records from Leiden Regional Archive

- Photographs of New York (Lincs – UK) and Pilgrim Fathers monument (Lincs – UK)

- Church of the Pilgrimage, founded after an 1801 schism

- Pilgrim Hall Museum Pilgrim history and artifacts

- Mayflower Steps All about the Mayflower and Pilgrim Fathers with a Plymouth (UK) focus. Many pictures

- The Mayflower Pub London The original mooring point of The Pilgrim Fathers’ Mayflower ship in Rotherhithe, London and the oldest pub on the River Thames

- Pilgrim ships from 1602 to 1638 Pilgrim ships searchable by ship name, sailing date and passengers.

- The Pilgrim Fathers, BBC Radio 4 discussion with Kathleen Burk, Harry Bennett & Tim Lockley (In Our Time, July 5, 2007)