Berytus

Berytus (/ˈbɛrɪtəs, bəˈraɪtəs/;[1] Phoenician: Biruta; Ancient Greek: Βηρυτός, romanized: Bērytós; Latin: Bērȳtus), briefly known as Laodicea in Phoenicia (Ancient Greek: Λαοδίκεια ἡ ἐν Φοινίκῃ) or Laodicea in Canaan from the 2nd century to 64 BCE, was the ancient city of Beirut (in modern-day Lebanon) from the Hellenistic period through the Roman and Early Byzantine period/late antiquity. The city had been rebuilt by the Seleucids in the 2nd century BCE over the ruins of an older settlement centred on a Phoenician port dating back to Iron Age III and Persian periods. Berytus became a Roman colonia that would be the center of Roman presence in the eastern Mediterranean shores south of Anatolia.[2] The veterans of two Roman legions under Augustus were established in the city (the fifth Macedonian and the third Gallic), that afterward quickly became Romanized and was the only fully Latin-speaking city in the Syria-Phoenicia region until the fourth century. Although Berytus was an important city, Tyre was made the capital of the Roman province of Phoenicia. "Of the great law schools of Rome, Constantinople, and Berytus", the law school of Berytus stood "pre-eminent".[3] The Code of Justinian (one part of the Corpus Juris Civilis, the codification of Roman law ordered early in the 6th century AD by Justinian I and fully written in Latin) was mostly created in this school.

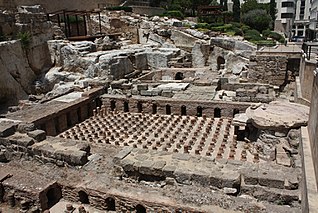

Roman ruins of Berytus, in front of Saint George Greek Orthodox Cathedral in modern-day Beirut | |

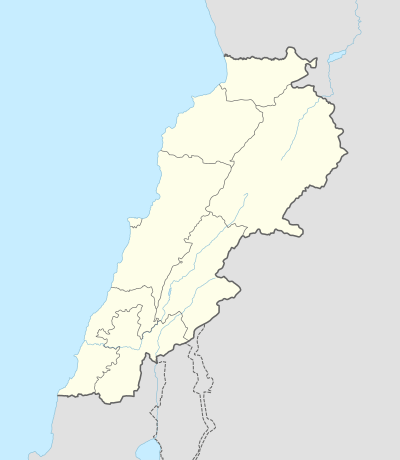

Shown within Lebanon | |

| Alternative name | Laodicea in Phoenicia (Ancient Greek: Λαοδίκεια ἡ ἐν Φοινίκῃ) or Laodicea in Canaan (2nd century to 64 BCE) |

|---|---|

| Location | Beirut, Lebanon |

| Coordinates | 33°53′44.8″N 35°30′18.5″E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Founded | (merchants from Berytus recorded by 110–109 BCE) |

| Periods | Hellenistic, Roman and Early Byzantine/late antiquity; previous port dating back to Iron Age III and Persian periods |

| Cultures | Phoenician, Greek, Roman |

History

Early history

In 140 BC the Phoenician village called "Biruta" was destroyed by Diodotus Tryphon in his contest with Antiochus VII Sidetes for the throne of the Macedonian Seleucid monarchy. Later it was rebuilt on a more conventional Hellenistic plan—the exact date is unclear but prosperous Berytian merchants were recorded in Delos by 110–109 BCE[4]—under the name of Laodicea in Phoenicia (Greek: Λαοδίκεια ἡ ἐν Φοινίκῃ) or Laodicea in Canaan in honor of a Seleucid Laodice.

The city was conquered by the Romans of Pompey in 64 BC and renamed "Berytus", as a reference to the name of the old original Phoenician port-village. The city was assimilated into the Roman Empire, veteran soldiers were sent there, and large building projects were undertaken.[5][6][7]

Roman colonia

In 14 BC, during the reign of Herod the Great, Berytus became an important Roman colonia. The city was named Colonia Iulia Augusta Felix Berytus in honor of Julia, the only daughter of Augustus (according to Theodore Mommsen, "Res gestae divi Augusti", II, 119). Furthermore, the veterans of two Roman legions were established in the city of Berytus by emperor Augustus: the fifth Macedonian and the third Gallic.[8] Consequently, the city quickly became fully Romanized. Large public buildings and monuments were erected and Berytus enjoyed full status as a part of the empire.[9]

...(Berytus) was made a Roman colony about 14 B.C. Herod the Great, Agrippa I and II, and Queen Berenice built exedras, porticos, temples, a forum, a theater, amphitheater, and baths here. In the 3d c. A.D. the city became the seat of a famous school of law and continued to flourish until the earthquake of A.D. 551 ravaged the city....Its streets, laid out on a grid plan, are spaced at roughly the same intervals as those of Damascus and Laodicea. The new Roman city spread farther S and W (of the port), with its Forum near the (actual) Place de l'Etoile. On its N side was a civic basilica 99 m long with a Corinthian portico of polychrome materials..., dating from the 1st c. A.D. Some large baths have been uncovered on the E slope of the (actual) Colline du Sérail, and the hippodrome lay on the NW side of the same hill. Some villas in a S suburb facing the sea had mosaic floors (now in the Beirut Museum).Some 12 km upstream on the Beirut river are the ruined arches of an aqueduct.[10]

Berytus was considered the most Roman city in the eastern provinces of the Roman Empire.[11] It was one of four Roman colonies in the Syria-Phoenicia region and the only one with full Ius Italicum (meaning: exemption from imperial taxation). Its territory under Claudius reached the Bekaa valley and included Heliopolis: it was the only area mostly Latin-speaking in the Syria-Phoenicia region, because settled by Roman colonists who even promoted agriculture in the fertile lands around actual Yammoune. From the 1st century BC the Bekaa valley served as a source of grain for the Roman provinces of the Levant and even for the same Rome (today the valley makes up to 40 percent of Lebanon's arable land):Roman colonists created there even a "country district" called Pagus Augustus.[12]

Agrippa greatly favoured the city of Berytus, and adorned it with a splendid theatre and amphitheatre, beside Baths and porticoes, inaugurating them with games and spectacles of every kind, including shows of gladiators. But now only minor ruins remains, in front of the Catholic Cathedral of Beirut.

Indeed, four large bath complexes as well as numerous private baths increased the city's water consumption: the Romans constructed an aqueduct fed by the Beirut River whose main source was located 10 km from the city. The aqueduct crossed the river at Qanater Zbaydeh and the water finally reached the place of actual Riad Al Solh Square; there, at the foot of the Serail Hill, it was stored in large cisterns. An intricate network of lead or clay pipes and channels distributed the water to the various pools of the Roman Baths.

Roman Berytus was a city of nearly 50,000 inhabitants during Trajan times and had a huge Forum and necropolis[13] The Hippodrome of Roman Berytus was the largest known in the Levant,[14] while literary sources indicate there was even a theater.[15] Scholars like Lynda Hall pinpoint that the hippodrome was still working in the fifth century [16]

Berytus had a monumental "Roman Gate" with huge walls (recently discovered[18]) and was a trade center of silk and wine production, well connected by efficient Roman roads to Heliopolis and Caesarea. According to Kevin Butcher,[19] the Latin character of Berytus remained dominant until the fifth century: the city was a center for the study of Latin literature and -after Septimius Severus- of Roman Law. Under Nero the son of a roman colonist, Marcus Valerius Probus (born in Berytus around 25 AD), was known in all the empire as a Latin grammarian and literature master philologist.

Roman emperors promoted the development of high-level culture in the fully Romanized city (even in Greek language as with Hermippus of Berytus).

The Law School of Berytus

The Berytian law school was widely known in the Roman empire;:[20] it was famous the Latin motto Berytus Nutrix Legum ("Beirut, Mother of Laws"). Indeed, two of Rome's most famous jurists, Papinian and Ulpian, both natives of Phoenicia, taught there under the Severan emperors.

When Justinian assembled his Pandects in the sixth century, a large part of the "Corpus of Laws" -all in Latin- was derived from these two jurists, and in 533 AD Justinian recognized the school as one of the three official law schools of the empire.

The law school of Beirut supplied the Roman Empire, especially its eastern provinces, with lawyers and magistrates for three centuries until the school's destruction in a powerful earthquake. After the 551 Beirut earthquake[21] the students were transferred to Sidon.[22]

Since the third century, the city had an important law college. It was here that the great codification of Roman Law, which was to be propagated by emperors like Theodosius II and Justinian, was prepared.[23]

Early Byzantine rule

Under the Eastern Roman Empire, some intellectual and economic activities in Berytus continued to flourish for more than a century, even if the Latin language started to be replaced by the Greek language.

However, in the sixth century a series of earthquakes demolished most of the temples of Heliopolis (actual Baalbek) and destroyed the city of Berytus, leveling its famous law school and killing nearly 30,000 inhabitants. Furthermore, the ecumenical Christian councils of the fifth and sixth centuries AD were unsuccessful in settling religious disagreements within the surviving community.

Berytus became a "Christian See" at an early date, and was a suffragan of Tyre in "Phoenicia Prima", a province of the "Patriarchate of Antioch". In antiquity its most famous bishop was Eusebius, afterwards Bishop of Nicomedia, the courtier-prelate and strong supporter of Arianism in the fourth century....In 450 AD Berytus obtained from Theodosius II the title of metropolis, with jurisdiction over six sees taken from Tyre; but in 451 AD the "Council of Chalcedon" restored these to Tyre, leaving, however, to Berytus its rank of metropolis (Mansi, VII, 85–98). Thus, from 451 AD Berytus was an exempt metropolis depending directly on the Patriarch of Antioch.[24]

This turbulent Byzantine period weakened the Romanized (and fully Christian) population and made it easy prey to the newly converted Muslim Arabs of the Arabian Peninsula.[25] Roman Berytus -reduced to the size of a village- fell to the Arabs in 635 AD.[26]

Recent discoveries

Recently at the Garden of Forgiveness the two main streets of Roman Berytus, the Cardo and Decumanus Maximus, were discovered in the Beirut Central District. Their shaded colonnades became busy markets on festival days. At other times, these streets would have been frequented by Law School students and citizens passing to the Forum or visiting temples and churches.

In 1968 were discovered the "Roman Baths" Gardens, that is a landscaped public space that lies on the eastern slope of the Serail Hill. It consists of a garden and a set of uncovered ruins of the ancient Roman baths of Berytus (hence the name of the place). These ruins underwent a thorough cleaning and further excavation in 1995–1997. Designed by the British landscaping firm Gillepsies, the Garden's layout is dominated with low-slung glass walls and lookout platforms that can be turned into concert venues, thus giving a 21st-century touch without harming the area's historical fabric.[27]

At the turn of the 20th century was identified the area were existed the famous school of Roman law at Berytus. Archaeological excavations in the area between the Saint George Greek Orthodox Cathedral and Saint George Cathedral of the Maronites unearthed a funerary stele etched with an epitaph to a man named Patricius, "whose career was consecrated for the study of law".[28] The epitaph was identified as being dedicated to the famous 5th-century law school professor.[29] In 1994, archaeological diggings underneath the Saint George Greek Orthodox Cathedral in Beirut Central District's Nejmeh Square identified structural elements of the Anastasis cathedral, but they were restricted to an area of 316 square metres (3,400 sq ft) and failed to unearth the interred school.[30] In the 5th century, Zacharias Rhetor reported that the school stood next to the "Temple of God", the description of which permitted its identification with the Byzantine Anastasis cathedral.[31]

Notable people

- Hermippus of Berytus (fl. 2nd century AD)

- Marcus Valerius Probus (c. 20/30 – 105 AD)

- Vindonius Anatolius

See also

Notes

- Worcester, Joseph E. (1861) An Elementary Dictionary of the English Language, Boston: Swan, Brewer & Tileston, page 326

- Theodore Mommsen."The Provinces of the Roman Empire" Chapter: Phoenicia

- https://books.google.com/books?id=KSQiAQAAIAAJ

- Paturel 2019, p. 72.

- About Beirut and Downtown Beirut, DownTownBeirut.com.

- Beirut Travel Information, Lonely Planet

- Czech excavations in Beirut, Martyrs' Square, Institute for Classical Archaeology, Archived July 23, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Hall, Linda Jones (2004). Roman Berytus: Beirut in Late Antiquity. Taylor & Francis.

- About Beirut and Downtown Beirut, DownTownBeirut.com. Retrieved November 17, 2007.

- Princeton E.: Berytus

- Morgan, James F. The Prodigal Empire: The Fall of the Western Roman Empire, page 87

- Butcher, 2003; p.230

- "Data with map of Roman Berytus (in Spanish)". Archived from the original on 2009-09-16. Retrieved 2015-08-19.

- "Roman wall removed from Beirut Hippodrome site". Beirut Report. October 25, 2013.

- Kevin Butcher (2003). Roman Syria and the Near East. Getty Publications. p. 230. ISBN 978-0-89236-715-3.

- Lynda Hall, p. 68

- "CNG: The Coin Shop. PHOENICIA, Berytus. Claudius. AD 41-54. Æ 20mm (8.92 g, 12h). Legionary issue". www.cngcoins.com.

- "Possible Roman gate and road found in Beirut dig". Beirut Report. May 17, 2013.

- Butcher, 2003; p. 230

- Beirut Archived 2012-05-24 at Archive.today, Britannica.com

- Archive, Full Text. "History of Phoenicia" – via www.fulltextarchive.com.

- History of Berytus Archived 2009-06-28 at the Wayback Machine

- "Livius: Berytus".

- Catholic E.:Berytus ()

- Gil, Moshe; Ethel Broido. "A History of Palestine". pp. 634–1099

- Donner, Fred McGraw (1981), "The Early Islamic Conquests". Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-05327-8

- "Beirut Shakes Off Rubble, Dons Slick New Architecture". Co.Design. 2010-08-11.

- Collinet 1925, p. 73

- Collinet 1925, pp. 61–73

- Skaf 2005, pp. 224–229

- Collinet 1925, pp. 63–73

Bibliography

| Look up Berytus in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Butcher, Kevin (2003). Roman Syria and the Near East. Los Angeles: Getty Publications. ISBN 978-0-89236-715-3.

- Collinet, Paul (1925). Histoire de l'école de droit de Beyrouth (in French). Paris: Société Anonyme du Recueil Sirey.

- Gil, Moshe (1997) [1983]. A History of Palestine, 634–1099. Translated by Ethel Broido. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-59984-9.

- Hall, Linda J. (2004). Roman Berytus: Beirut in Late Antiquity. London: Psychology Press. ISBN 978-1-134-44013-9.

- Mann, J.C. The settlement of veterans in the Roman Empire London University. London, 1956

- Mommsen, Theodore. The Provinces of the Roman Empire from Caesar to Diocletian. Press Holdings International. New York, 2004. ISBN 9781410211675

- Mouterde, René et Lauffray, Jean (1952) Beyrouth ville romaine. Publications de la Direction des Antiquités du Liban, Beyrouth.

- Paturel, Simone (2019). Baalbek-Heliopolis, the Bekaa, and Berytus from 100 BCE to 400 CE: A Landscape Transformed. Brill.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Skaf, Isabelle; Yasmine Makaroun Bou Assaf (November 29 – December 3, 2005). Aïcha Ben Abed Ben Khader; Martha Demas; Thomas Roby (eds.). Une nouvelle approche pour la préservation in situ des mosaïques et vestiges archéologiques au Liban: La crypte de l'église Saint-Georges à Beyrouth. Lessons Learned: Reflecting on the Theory and Practice of Mosaic Conservation (9th ICCM Conference, Hammamet, Tunisia) (in French). Getty Publications. ISBN 9780892369201.